Above: Protestors at Cove Point Rally in Baltimore, Feb. 20, 2014.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) on May 15 issued its Draft Environmental Assessment (EA) on the Cove Point LNG terminal expansion. The draft EA concludes that the Cove Point project would not “significantly affect the quality of the human environment” and recommends a finding of “no significant impact.” It further stipulates eighty-two measures to mitigate potential impacts of the project before it can be authorized.

Dominion Resources, which applied to FERC to convert its liquefied natural gas import terminal into an export facility, is proclaiming victory. “FERC says Cove Point can be built safely with no significant impact to the environment,” Dominion said in a press release.

With the release of the draft EA, Dominion is close to surmounting a major regulatory hurdle. “The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission [is]… to be commended for their thorough and independent assessment,” said Dominion Energy’s President, Diane Leopold, via press release. “This [report] marks another important step forward.”

The real victory that Dominion has achieved with FERC’s Environmental Assessment, however, is limiting the regulatory agency from assessing the full scope of the Cove Point project.

Environmental, public interest and community groups are calling on FERC to “go back to the drawing board.” For months now, they have been pushing for FERC to conduct an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). The draft EA does take into account factors such as air quality and noise, the local population and economy, and impacts on the surrounding wetlands, fisheries, and soil. But an EIS is broader in scope and requires “a higher standard of scrutiny.”

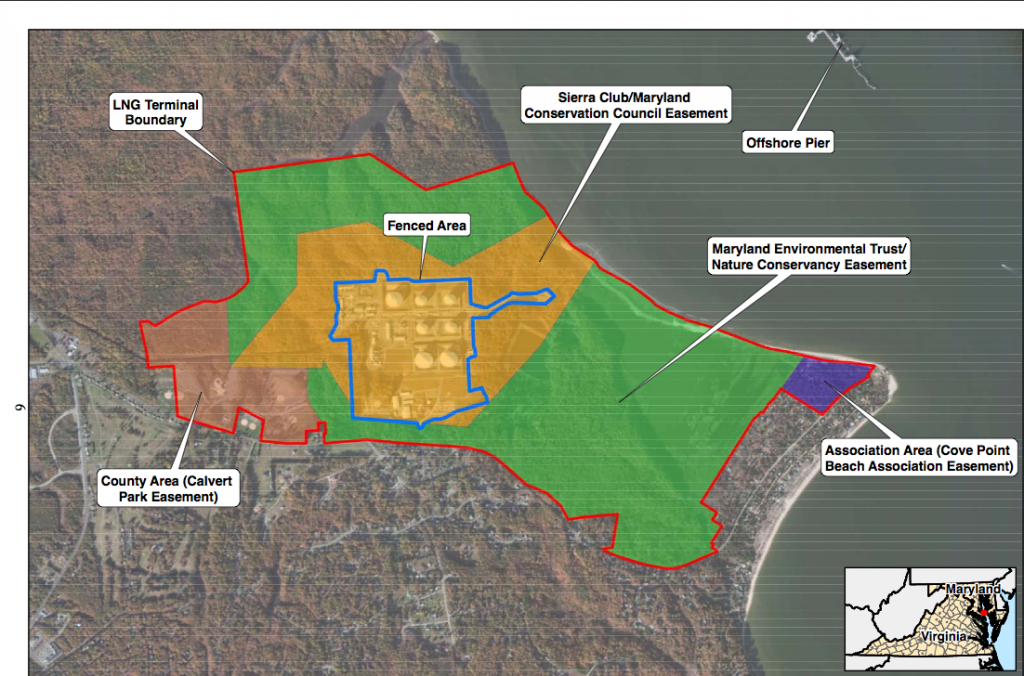

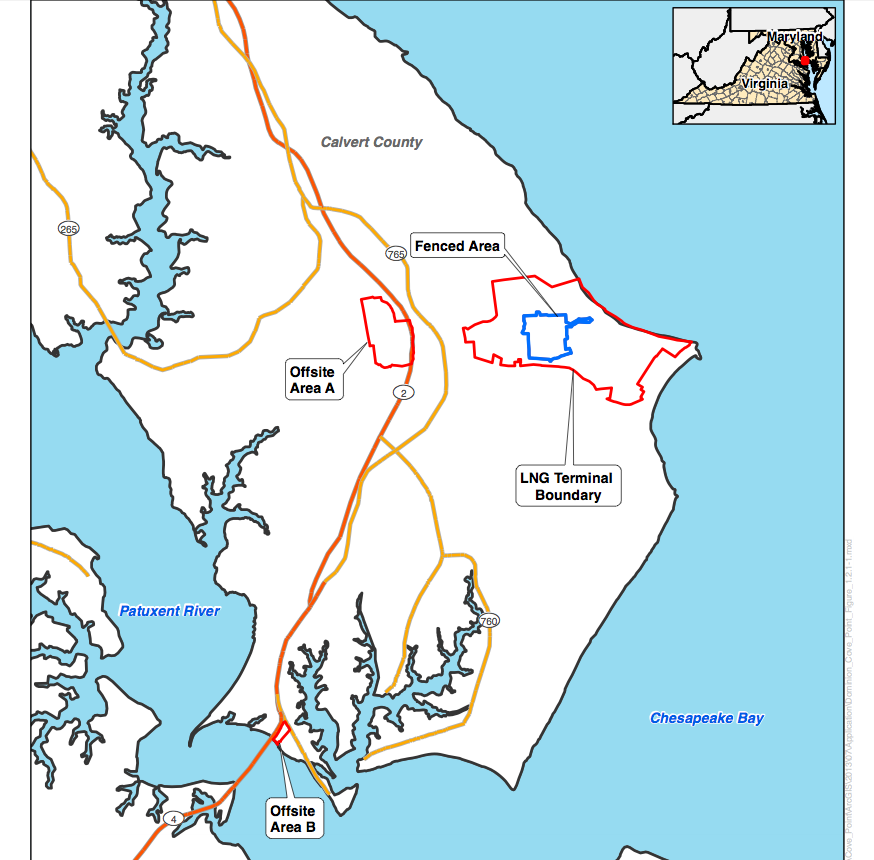

To hear Dominion tell it, the Cove Point project is confined to a 150-acre lot on the Chesapeake Bay. Nothing will extend beyond the fence where the Cove Point import terminal was built 40 years ago. “This project will be built within the existing footprint and fence line of an industrial site,” Leopold said. “There is no need for additional pipelines, storage tanks or permanent piers, thus limiting its impact and making an environmental assessment appropriate.”

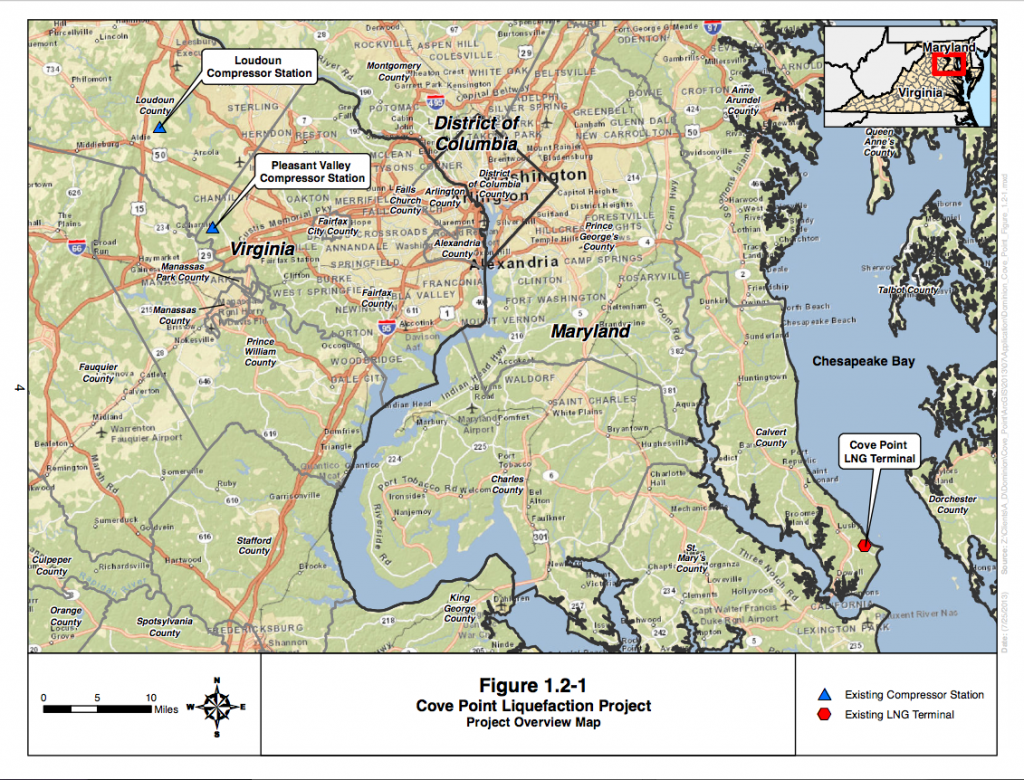

Leopold must have forgotten that Dominion’s own application to FERC included more than the liquefaction train, refrigerant compressors, and turbine generators on 55 acres of the fenced-in area, as well as modifications to the off-shore pier. According to the EA, Dominion needs significant upgrades to its Pleasant Valley Compressor Station in Fairfax County, Virginia and modifications to its Loudoun County, Virginia Compressor Station.

Plus, Dominion asked for approval to buy, lease and clear-cut 150 acres of land for staging construction. It’s already begun road construction to handle increased truck traffic.

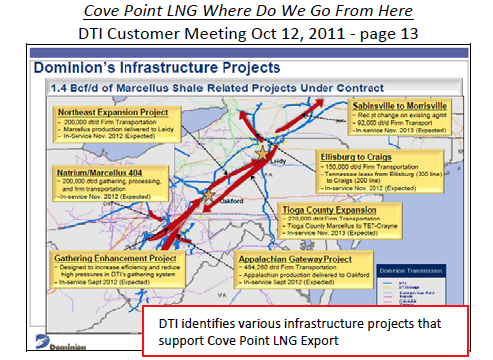

Leopold wouldn’t lose much by ‘fessing up to the Virginia compressor stations. In getting an Environmental Assessment done rather than an EIS, Dominion managed to conceal Cove Point’s very large footprint. A whole lot of infrastructure is needed to get natural gas to Cove Point, and Dominion has been laying the groundwork for years.

The town of Myersville, Maryland has been fighting the construction of a highly polluting, noisy compressor station near its elementary school. Ann Nau, who’s been spearheading that battle, said Dominion and other energy companies strategically plan infrastructure projects with permitting in mind.

“Industry makes it seem that these projects are not connected in order to apparently minimize the impacts to FERC, so that they to do the EA instead of the more comprehensive EIS,” she said.

The Myersville compressor station is just one example of this. The 16,000 horsepower station is supposedly needed to fulfill Dominion Transmission’s contract to Baltimore Gas and Electric and Washington Gas Light.

But, according to Nau, “it’s completely overbuilt.” The Myersville station would have four times more horsepower than another proposed station intended to push 40% less volume. Dominion publicly denies any connection between the Myersville station and Cove Point, but internal documents indicate otherwise.

The Myersville compressor station and other pipelines and midstream facilities would transport natural gas from fracking wells of the prolific Marcellus Shale to Cove Point. This brings fracking, a federally unregulated, “unconventional” extraction method, into the big picture of Cove Point.

In a letter sent to President Obama in March 2014, leaders of sixteen environmental and pubic interest groups framed the totality of the Cove Point project this way:

The lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions of the LNG export process—including drilling, piping, compressing, liquefying, shipping, re-gasifying, and burning—likely make it as harmful to the climate, or worse than, burning coal overseas. Analysis shows the $3.8 billion Cove Point plan could alone trigger more lifecycle climate change pollution than all seven of Maryland’s existing coal-fired power plants combined.

When it suits Dominion, it not only acknowledges that Cove Point would play a role on the global stage, it brags about its vital importance:

This one project could reduce the nation’s trade deficit by up to $7 billion annually while helping two important allies, Japan and India, meet urgent clean-energy needs. At the same time, the United States can continue to have ample natural gas supplies to meet domestic needs, and U.S. industry can maintain a significant energy price advantage over international competitors.

One element is missing from both of these pictures: people. Cove Point would be the first LNG export facility built in a population dense area; 360 homes are within the “consequence zone” of a catastrophic event. Children at the Myersville elementary school would breathe fumes from a station belching 23.5 tons of nitrogen oxide a year. Pipelines emitting methane and prone to spills and explosions are being built through populous areas. Fracking wells are contaminating drinking water and causing respiratory and neurological disorders.

“They can mitigate the impacts, but does that make it okay?” asks Ann Nau. “What is okay when it comes to mitigating the impact on our children?”

Related: