Above Photo: Les Stone Photography

For many living along Carter Road, this coming summer will mark their ninth year living without access to a regular supply of clean drinking water – and still the legal battle stretches on.

For many residents of Carter Road in Dimock, Pennsylvania, it’s been nearly a decade since their lives were turned upside down by the arrival of Cabot Oil and Gas, a company whose Marcellus Shale hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) wells were plagued by a series of spills and other problems linked to the area’s contamination of drinking water supplies.

With a new federal court ruling handed down late last Friday, a judge unwound a unanimous eight-person jury which had ordered Cabot to pay a total of $4.24 million over the contamination of two of those families’ drinking water wells. In a 58 page ruling, Magistrate Judge Martin C. Carlson discarded the jury’s verdict in Ely v. Cabot and ordered a new trial, extending the legal battle over one of the highest-profile and longest-running fracking-related water contamination cases in the country.

In his order, Judge Carlson chastised the plaintiff’s lawyers for “repeatedly inviting the jury to engage in unwarranted speculation” and wrote that, in his personal estimation, the plaintiffs had not presented enough evidence to warrant the jury’s $4.24 million in damages. The original complaint for the case was filed in November 2009.

Nonetheless, Judge Carlson declined to throw out the lawsuit entirely, ordering Cabot to re-start settlement talks with the Ely and Hubert families. If those talks fail, the trial process will begin anew, extending the already years-long legal battle into months or even years to come.

“The judge heard the same case that the jury heard and the jury was unanimous,” Nolan Scott Ely, the lead plaintiff in the case, said in a statement. “How can he take it upon himself to set aside their verdict? It’s outrageous.”

Retrials “not as rare”

Over time, Judge Carlson’s order noted, the plaintiffs’ legal complaints had been successfully winnowed down by Cabot, which was represented at trial by several lawyers from Norton Rose Fulbright, the tenth highest-grossing law firm in the world in 2016. The case now centers around a nuisance complaint.

Ely, whose background is in construction work, and his family and neighbors were represented at trial by a solo practitioner, Leslie Lewis, assisted by one other attorney. During one brief stint in the years leading up to the trial, the two families had no lawyer at all, but represented themselves. When the case began, they had the assistance of the firms Napoli Bern Ripka Shkolnik & Associates and the Jacob Fuchsberg Law Firm (the former employer of Lewis), which ushered in a settlement agreement with some of the 44 original plaintiffs.

But Ely and others were not satisfied with the offer, which included a non-disclosure agreement, and decided to proceed with the lawsuit.

John-Mark Stensvaag, an environmental law professor at the University of Iowa, said that orders to re-try cases “are not as rare as one might think.”

“This does not mean that the plaintiffs have no case,” he added, “it only means that, in [Judge Carlson’s] opinion, they have not presented a case justifying the jury’s verdict and should be given a second opportunity to present an adequate case.”

Carter Road Water Contamination

There’s little question that something is very wrong with the water on Carter Road, despite lingering questions in the legal battles centering around that contaminated water.

In 2016, shortly after the Elys and Huberts’ $4.24 million verdict, the Centers for Disease Control issued a report concluding that Dimock’s tainted waters carried dangerous levels of chemicals including arsenic, lithium, and 4-chlorophenyl phenyl ether (which is acutely toxic if swallowed). Further, the water was laced with enough methane that five of the homes on Carter Road had been at risk of exploding. Indeed, on New Year’s Day 2009, one of Dimock’s contaminated drinking water wells did explode.

In 2010, the state’s Department of Environmental Protection concluded that Cabot’s drilling operations had contaminated the drinking water supplies of 19 homes in Dimock and reached an agreement with Cabot requiring the company to pay out $4.6 million over the harm to the families’ wells. Most of the families on Carter Road separately settled their lawsuit against Cabot in the midst of the 2012 presidential race, under terms that included a gag order barring them from speaking publicly about the terms of the settlement.

Also in 2012, the Obama administration’s U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a press statement in July, concluding that drinking water was safe for consumption on Carter Road, even though it privately told those in the community not to drink it.

“Our goal was to provide the Dimock community with complete and reliable information about the presence of contaminants in their drinking water and to determine whether further action was warranted to protect public health,” Shawn Garvin, then the Administrator for EPA Region 3 and current secretary of the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, said in the statement. “The sampling and an evaluation of the particular circumstances at each home did not indicate levels of contaminants that would give EPA reason to take further action. Throughout EPA‘s work in Dimock, the Agency has used the best available scientific data to provide clarity to Dimock residents and address their concerns about the safety of their drinking water.”

A PowerPoint presentation obtained by DeSmog and published in 2013 shows that EPA scientists had concluded there was a definitive link between the drilling in the area and water contamination. That presentation was barred from being entered into evidence by Judge Carlson, despite the plaintiffs’ request to present it to the jury.

Evidence catch-22

An underlying theme of the case for the plaintiffs’ attorney Lewis and her clients has centered around a struggle over the evidence the plaintiffs could present to the jury, which has come back to haunt them with the recent ruling by Judge Carlson.

Beaten back with nearly every attempt to present evidence to the jury, Lewis’s team faced difficulty in presenting its full case to the court. But it is now caught in a catch-22, punished by the Judge for its attempts to enter evidence and accused of biasing the jury in the process.

Just before trial began, Judge Carlson had handed down a scathing ruling in February 2016 rejecting hundreds of exhibits that the plaintiffs had offered into evidence, which he said had not been turned over to the defendants soon enough.

The ruling severely constrained the evidence Lewis was permitted to present during trial. For example, in the middle of Lewis cross-examining a witness for the case, the topic of the leaked EPA PowerPoint arose again during a March 4, 2016 sidebar conversation, after Cabot attorney Amy Barette raised an objection to Lewis’s line of questioning. Judge Carlson ordered Lewis not to broach the topic of the PowerPoint, pointing to the July 2012 EPA press statement.

Nonetheless, the jury unanimously concluded that Cabot was liable – a conclusion that Judge Carlson’s new order discards, while slamming the plaintiffs’ lawyers for alluding to prohibited evidence in front of the jury. He described the plaintiffs as engaging in a “concerted pushback” against the natural gas industry, while noting that “many other residents welcomed the industry’s arrival and expansion.”

Battles over evidence like those seen in the Dimock water contamination case are well-studied in the legal scholarly community, and addressed in depth in the recent book The Psychological Foundations of Evidence Law.

“An attorney’s objection signals [to] the jury that the objected-to testimony is an important secret: something one side does not want them to know about or use,” wrote book co-authors Michael Saks and Barbara Spellman, law professors at Arizona State University and the University of Virginia, respectively. “The testimony must be important because the lawyer is spending the time (and is willing to annoy the judge) to make sure that they do not learn it.”

Timeline for Dimock water contamination

Judge Carlson’s order throwing out the jury’s verdict also refused to allow the two families to dispute a fact that emerged as one of Cabot’s crucial defenses, a claim that the Gesford 3 well – suspected as a primary cause of the pollution – was drilled after the Elys first noticed their water had gone bad.

“The aggregate effect of this repeated trespass into prohibited areas was compounded during a highly irregular closing argument, which ultimately created the impression for the jury that Cabot must have been responsible for all of the plaintiffs’ alleged water problems – problems that began before the Gesford wells were drilled, a fact that we now know because the plaintiffs stipulated to it before trial,” Judge Carlson wrote.

Under that “binding stipulation,” Cabot’s Gesford gas wells, Judge Carlson wrote, were drilled in “late September 2008” – a critical date because of a handwritten note in which Ely said that he first noticed something was wrong with his water in the summer of 2008.

“The evidence unquestionably showed that the plaintiffs had begun experiencing some problems with their water before the spud date for the Gesford wells,” Judge Carlson wrote (using the term “spud date,” or the date that drilling began).

Part of the problem is that many of the wells near Carter Road have virtually identical names and it’s not clear that the plaintiffs intended their stipulation to cover all of the “Gesford” wells. What is clear is that state records (later confirmed in the EPA‘s national study on fracking, found on page 521) show that Gesford 3 – one of Cabot’s most troubled gas wells – was “spud” on May 28, 2008.

The state records reflect information submitted by the drilling company (meaning that they reflect information reported by Cabot to the state) and show two other Gesford wells, 2 and 9, were drilled later that fall – but the Gesford 3 date is crucial because it shows that drilling happened before the Ely family first noticed their water had gone bad, not after.

The state records reflect information submitted by the drilling company (meaning that they reflect information reported by Cabot to the state) and show two other Gesford wells, 2 and 9, were drilled later that fall – but the Gesford 3 date is crucial because it shows that drilling happened before the Ely family first noticed their water had gone bad, not after.

State and federal records also show that Cabot was cited for violating state environmental laws at the Gesford 3 well on June 3, 2008 – a time when Judge Carlson’s order insists that Gesford 3 had not yet been drilled.

Industry pressure, celebration

Judge Carlson, who is up for re-appointment in August, has been considering Cabot’s appeal of the jury’s verdict for nearly a year. Initially, Judge Thomas Vanaskie had been hearing the case, but in 2010 he was confirmed by the U.S. Senate to fill the vacancy on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit.

Upon leaving for the Appeals Court, Vanaskie handed the case off to Judge John E Jones III, who helped broker the 2012 settlement. Jones, at the time of the brokered settlement, had financial investments in several Marcellus Shale drillers, including Chesapeake Energy, Shell, and Dominion Resources.

Oil and gas industry advocates, such as the entities Energy In Depth, Natural Gas Now (run by former Energy in Depth staffer Tom Shepstone), and FrackNation, have cheered on Judge Carlson’s ruling.

“This saga is a textbook example of how the anti-fracking crowd gets a rumor of something occurring and runs with it in a shameless effort to advance an agenda of stopping oil and gas development across the country,” wrote Nicole Jacobs, deputy campaign director for Energy in Depth Northeast, in an April 3 blog post. “And who suffers? The people of Dimock, who have spent years trying to help people see the gross mischaracterization of their community that started with [the film] Gasland.”

“FrackNation” at trial

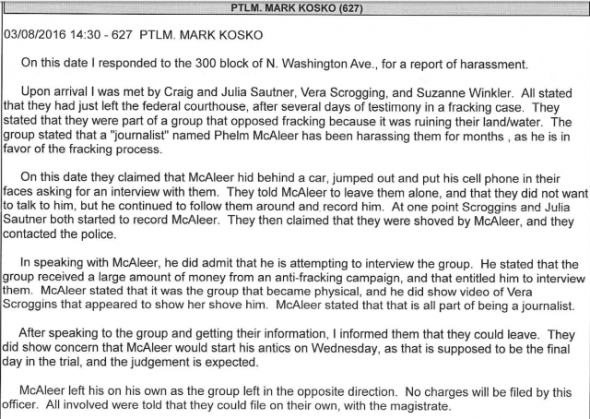

Phelim McAleer, the industry-funded director and producer of the pro-fracking film FrackNation – whose film misleadingly attempted to debunk the Carter Road water contamination complaints – actually harassed one of the expert witnesses during the trial, Cornell University’s Anthony Ingraffea. Ingraffea, a professor of civil and environmental engineering, is best known for his studies on well casing integrity failures and fugitive methane emissions which occur during the shale oil and gas horizontal drilling process.

In a June 2016 court filing, Lewis and her co-counsel Elisabeth Radow outlined McAleer’s conduct, behavior which included recording on his cell phone during the trial in defiance of court rules and interacting with trial participants, which they alleged appeared to be done in concert with Cabot’s counsel.

“Plaintiffs’ expert witness observed and overheard associate attorney for Cabot, Lauren Brogdon, actively encourage Mr. McAleer to approach Ms. Lewis in the Courtroom, whereupon he threatened her with the statement, ‘You better watch your step,’” they wrote in the filing. “This conduct was immediately reported to the Court.”

They also discussed the filming incident in the court filing, noting that McAleer posted the video on YouTube and disseminated it in a blog post. McAleer’s behavior led to a meeting held between the two legal teams and Judge Carlson, in which Carlson ordered for the federal Marshals Service to get more directly involved in policing McAleer’s behavior.

“Specifically, following the meeting in chambers, the Court ordered the presence of federal marshals to police the Courtroom for the duration of the trial,” they wrote. “Defendant’s surrogate, Mr. McAleer, disregarded the Court’s admonition to refrain from recording in, and transmitting from, the Courtroom, requiring a federal marshal to usher him from the Courtroom before the trial resumed for the afternoon session. On that occasion, and as Mr. McAleer was being physically ushered out of the Courtroom, [Cabot’s attorney] was observed to have stormed out of the Courtroom after the federal marshal.”

In a declaration exhibited and attached to the court filing, Ingraffea swore under the penalty of perjury that he saw McAleer working in concert with Cabot’s attorney Lauren Brogdon on the sidelines of the jury trial.

Ely, the lead plaintiff at the trial, also said he was harassed by McAleer in a sworn testimony exhibited as part of the same June 2016 court filing submitted to the court by Lewis and Radow.

Ely alleged that during a conversation he was having with Lewis and Radow in front of the courthouse after the trial ended for the day, McAleer stuck a cell phone in their faces and asked Ely, “Why do you make your daughter smell your water?” The question was in reference to a sworn statement cross-examination which took place during the trial between Ely’s daugther, Jessica Ely, and Cabot’s attorney Amy Barrette.

Other anti-fracking activists who attended the trial – including former Carter Road residents Julia and Craig Sautner, who previously told DeSmog that McAleer took an interview they did out of context and used the footage in the film FrackNation – reported to the Scranton Police Department that McAleer partook in similar harassment activity outside, according to an incident report obtained by DeSmog.

As a result of McAleer’s conduct, Judge Carlson ordered the jury to be placed under escort by federal marshals when they entered and left the courthouse during the remainder of the trial.

More recently, McAleer inserted himself into the protests against the Dakota Access pipeline at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota, alleging he was assaulted by those at the encampment. A DeSmog open records request for the incident report published by the Morton County Sheriff’s Department was denied, while one submitted to the U.S.Bureau of Indian Affairs is pending.

“Guts are full of tumors”

Ray Kemble, who lives just around the corner from the Elys, never settled with Cabot and did not participate in the Elys’ lawsuit though he has testified before the EPA. He keeps a collection of water bottles filled with strange fluids – sometimes ecto-cooler green, sometimes brown with iridescent swirls – drawn from water wells on Carter Road.

In an interview with DeSmog, Kemble said that he was diagnosed with bladder cancer on March 16, an ailment he blames squarely on contamination from Marcellus Shale drilling activity in Dimock.

“My guts are full of tumors,” Kemble said. But he hasn’t been able to afford to move, in part because no one will buy his house, given that his water is contaminated.

“I worked it for almost four years, plus I’m living in it,” said Kemble, who formerly worked as a truck driver for the drilling industry. “We were drinking and bathing in it because we didn’t know back in ’09 and ’10.”

“Dark chapter”

Cabot was allowed to stop delivering drinking water to Carter Road in 2011. A promised water line, which would connect the homes to municipal water, was never built.

Attorneys for both parties in the Ely case have been ordered to submit a confidential settlement memorandum, 14 days prior to the settlement conference, on or before April 27. Two weeks later, the parties will hold that conference at the federal courthouse in Scranton, Pennsylvania, on May 11 and May 12, with the convening to be overseen by Magistrate Judge Karoline Mehalchick.

“It is a miscarriage of justice,” John Hangar, former secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection under Governor Ed Rendell, wrote on Facebook of the jury verdict reversal. “Lots of evidence was excluded [and] I might get involved in a retrial.”

“This decision marks another dark chapter for the victims of water contamination from gas drilling operations,” said Lewis in a statement. “Plaintiffs do not believe that the Court’s decision fairly reflects the record, or the totality of what transpired in the courtroom over the ten day trial.”

For many living along Carter Road, this coming summer will mark their ninth year living without access to a regular supply of clean drinking water – and still the legal battle stretches on.