Above Photo: Some of the most viable options identified by the IPCC for capturing and storing carbon are based in the natural world. Credit: Joel Saget/AFP/Getty Images

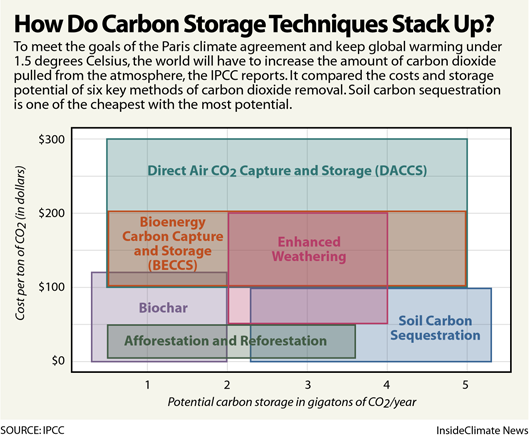

Soil leads the solutions for negative emissions in a new climate change report. Soil carbon sequestration was among the cheapest methods with the greatest potential.

The UN’s latest global warming report made it clear that if the world is to avoid the worst impacts of climate change, society urgently needs to move away from fossil fuels completely.

But to keep the planet from warming more than 1.5 degrees Celsius, the report says, we’ll also have to figure out how to undo some of the damage that’s already been done.

“Given our current knowledge, we can’t get to 1.5 degrees without removing carbon from the atmosphere and storing it,” said Kelly Levin, a senior associate at the World Resources Institute.

With 1.5°C of warming just around the corner, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) considered several solutions for removing CO2 from the air—some as simple as planting more trees, others as complex as using technology to filter CO2 from the air. Their practicality and their risks vary considerably.

Some of the most viable options identified by the IPCC are based in the natural world, as opposed to more costly technologies that aren’t yet proven on large scales.

Of the options considered, the solution the IPCC found to have both the most potential for reducing CO2 and the lowest costs was what’s known as soil carbon sequestration.

How Soil Carbon Sequestration Works

The way soil carbon sequestration works is well understood, explained Deborah Bossio, the lead soil scientist with the Nature Conservancy. When plants grow, photosynthesis absorbs carbon dioxide from the air and converts the carbon to a more stable form under the ground. If farmers use certain practices, such as farming without tilling the soil and leaving the ground covered for longer, more carbon gets stored in the ground.

“You have so many agricultural fields that only have crops during one season, and the rest of the year it’s this bare dirt,” Bossio said. “We’re talking about growing things during those other times to increase the amount of carbon that can be stored.”

The IPCC found that by 2050, soil carbon sequestration could remove between 2 and 5 gigatons of carbon dioxide a year, at a cost ranging from less than $0 to $100 per ton. (For comparison, technology that can capture CO2 released by the burning of biomass—known as BECCS—was estimated to be able to capture between 0.5 and 5 gigatons of carbon a year at costs ranging from $100 to $200 per ton).

There is some concern that soil carbon sequestration only works for as long as farmers keep it up. For example, if a farmer adopts practices to store carbon but then a generation later that farm abandons that approach, the carbon could slowly be lost again.

The IPCC said it had “robust evidence” that climate-friendly farming would work. It doesn’t impact water resources, or require vast amounts of land to be taken out of food production. And it is low-hanging fruit, starting at zero cost or even better because it offers side benefits, like improved soil quality and food security, even without a boost from climate policies.

Other Negative-Emissions Options

Experts expect that any path forward for limiting global warming will include a “portfolio approach” of several negative emissions technologies.

“What the IPCC report tells you is that if you do it all, these doors in front of us are closing rapidly,” said Klaus Lackner, director of the Center for Negative Carbon Emissions at Arizona State University.

Among the options the IPCC explored:

- Afforestation and reforestation: Simply put, more trees means less carbon in the atmosphere. But offsetting emissions from fossil fuels would require huge forests, competing with food production and posing other problems.

- Carbon capture and storage: This basically is a way to continue burning fossil fuels by capturing their greenhouse gases and storing them, keeping them out of the atmosphere. So far, governments have been unwilling to pay for CCS on a large scale. A few projects are running, but many others have been cancelled.

- Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage: Burning trees or other crops instead of fossil fuels in power plants, then capturing the CO2 from the smokestacks and storing it underground, would require huge tracts of land and risky changes to ecosystems.

- Direct air capture and storage: When air flows past a direct capture system, the carbon dioxide is selectively removed. It’s then released as a concentrated stream for storage or use. This technology is currently in operation on a small scale, but the size and cost of the equipment could make it hard to scale up.

- Enhanced weathering: By adding minerals to oceans and soils, enhanced weathering promotes a natural process by which carbon dioxide is converted to a solid and decomposed. It is expected to be able to remove carbon on a smaller scale than the other technologies.

These technologies have been studied for decades but have been met with skepticism along the way.

Lackner said that over the years, there was concern that focusing on a technological solution might slow progress toward mitigating emissions. But now it’s not an either-or choice. “There’s no real practical solution that will keep us in this window [of 1.5°],” Lackner said. “We will have to figure out how to create large-scale negative emissions because we have entered an overshoot regime.”

Over-Optimistic About Tech Solutions?

Earlier this year, the European Academies’ Science Advisory Council (EASAC) issued a report saying that scientists and policymakers were being “seriously over-optimistic” about just how effective carbon capture and storage technology could be at staving off climate change. They pointed to the relatively untested nature of many of the technologies and worried that focusing on technology could slow mitigation efforts.

Thierry Courvoisier, president of EASAC, said he still has those concerns but agreed with the IPCC’s findings of the urgency required to deal with global warming and the importance of both cutting emissions and removing existing carbon dioxide in achieving climate goals.

“One certainly needs a major paradigm shift in the quality of action that we—being not individuals but societies—take in order to achieve these goals,” he said. “If we just let things go and let the markets decide what’s good or not, we’re never going to get anywhere, and probably very decisive, state-led action is needed to change this paradigm.”

Levin, of WRI, said the real risk is waiting to start investing in these technologies. “If you don’t start now, if you flash forward two, three decades from now and if we haven’t made this a possible solution, there aren’t going to be safe and prudent options left,” she said.

“The report shows that not only do we need to act now and in a deep way, but we need a massive transition that’s a departure from the way we live our lives and operate our systems,” Levin said. “When you look at the math closely you see what a wild challenge this is.”