Read Part I here.

1920 to 1949

Birth Pangs and Growing Pangs

While the Bank of North Dakota attempted to establish itself on a firm and responsible foundation, difficulties arose from three fronts:

First, the League-owned Scandinavian American Bank of Fargo went into receivership in February 1921, after audits revealed a number of marginal and worthless loans, and inept management. Many people around the United States wrongly assumed that the bank in question was the experimental Bank of North Dakota (BND). Even among those who made the distinction, BND suffered by association.

The Scandinavian American Bank had been having significant troubles all the way back to 1919, two years after the NPL purchased it. It had survived those solvency and administrative crises for political, rather than sound financial, reasons.

With all the scandals, crises, publicity, open criticism, and political maneuvering since 1917, and now the collapse of the Fargo bank, the people of North Dakota had ample reason to doubt the financial sophistication of the Industrial Commission, the Bank’s managers and the League’s financial acumen. In other words, the continuing crisis of the League’s own bank caused many well-meaning Americans to doubt the credibility of the more ambitious state experiment in banking. The charge of general incompetence tainted all of the League’s enterprises.

Second, a number of outside observers, including Bill Langer who was a well-known NPL figure, believed that J.R. Waters, the Bank’s first manager, was incompetent. They called for his removal and used their assessment to discredit the whole idea of the bank.

Third, bond sales that would fund the state’s new industries proved to be a very considerable challenge.

Organized Opposition Tried to Take the Bank Down

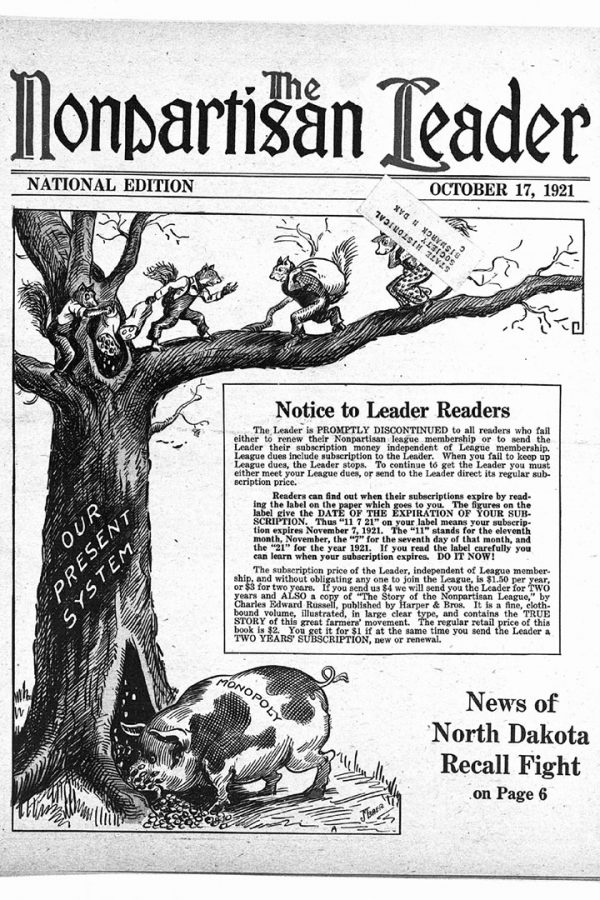

The easiest way to defeat the Nonpartisan League was to associate it with socialism and communism, or to accuse it of unpatriotic behavior or to deride the farmer citizens of North Dakota as rubes. The Dayton Press in Washington state wrote, “No wonder that the Nonpartisan bunk became so popular in North Dakota. The census taker found only five bathtubs in four counties. Uncleanliness and ignorance are ever companions, instance the Bolsheviki in Russia and the Bolsheviki hoboes of the I.W.W. and other unclean classes in the United States.”

Opposition to the League was fierce. NPLers were accused of being socialists, communists, anarchists and losers who preferred to seek government handouts rather than do the hard work of succeeding at farming. League supporters, especially political candidates, were subject to intense commercial discrimination in their hometowns.

The U.S. Supreme Court Challenge

On April 19, 1920, the nine justices of the United States Supreme Court heard appeals from Scott v. Frazier and Green v. Frazier challenging the constitutionality of North Dakota’s state-owned enterprises, including the Bank of North Dakota. The justices had a hard time understanding why the enterprises should be regarded as an infringement of the Fourteenth Amendment rights of North Dakotans.

Court (Justice James Clark McReynolds): “Why shouldn’t the state operate a bank?”

N.C. Young (representing the taxpayers): “It might properly do so for bona fide banking purposes of its treasury, but this bank is started merely to finance these industries.”

Court: “Well, and why should not the state go into business?”

Young: “Why, that is taking money from the taxpayer without due process.”

Court: “That is merely words. We are interested in reasons.”

On June 1, 1920, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the League enterprises in both cases.

Associate Justice William R. Day delivered the opinion of the Court. He declared: “If the State sees fit to enter upon such enterprises as are here involved, with the sanction of its constitution, its legislature, and its people, we are not prepared to say that it is within the authority of this Court, in enforcing the observance of the Fourteenth Amendment, to set aside such actions by judicial decision.”

Day said, “With the wisdom of such legislation, and the soundness of the economic policy involved we are not concerned. Whether it will result in ultimate good or harm it is not within our province to inquire.”

What mattered was that the Bank of North Dakota and the North Dakota Mill and Elevator were legal institutions.

As the Cincinnati Post put it, “the decision merely permits the people of a State to do what the majority wants done, and which is not in conflict with the Federal Constitution.”

The Independent Voters Association maneuvers

In North Dakota, the opposition formed the Independent Voters Association (IVA), but in neighboring Minnesota the opposition took on a more formidable name: Commission of Public Safety.

The IVA did not oppose the entire League program as enacted in 1919, but it did oppose two League programs with all its rhetorical force:

First, the Bank of North Dakota.

Second, the new Industrial Commission.

North Dakota historian D. Jerome Tweton wrote, “Nothing upset IVAers more than the thought of the state going into the banking business. The Independent [the IVA newspaper] dwelled on the failures of state banking businesses in American history and on the un-American and undemocratic philosophy upon which the Bank of North Dakota was founded. Especially distasteful to the paper and to the IVA was the requirement that all public funds be deposited with the bank and that control rest in the hands of the Nonpartisan League-controlled Industrial Commission.”

If the bank must exist, the IVA insisted that it be controlled not by politicians (the elected Industrial Commission), but by nonpolitical administrators.

The IVA tried to destroy the new state industries by way of hostile audits, and by cooperating with eastern financial interests to boycott the Bank or to purchase North Dakota bonds only if the state severely chastened its industrial enterprises. They worked hard in 1921 to reduce the Bank of North Dakota to a farm loan agency.

The showdown came on October 28, 1921, when League opponents recalled the three members of the Industrial Commission, including Governor Lynn J. Frazier, Agricultural Commissioner John Hagan and Attorney General William Lemke.

It was a dark day for the Nonpartisan League. The citizens of North Dakota had become convinced that the League leadership was incompetent and—according to some—corrupt. The recall was successful—all three League members of the Industrial Commission were recalled and replaced—but the opposition’s attempt to dismantle the League’s economic and Industrial Program through a series of initiated measures failed. By a margin of 4,238 votes, the people of North Dakota rejected a measure that would have abolished the state-owned Bank.

The most shocking decision was the recall of Lynn J. Frazier, the mild-mannered and thoroughly decent farmer-governor from Hoople, ND. Frazier was the first sitting governor to be recalled in the history of the United States. The next successful gubernatorial recall did not occur until 2003 when Gray Davis was replaced in California by Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The irony of Frazier’s recall is palpable. It was the Nonpartisan League that enacted recall, in the famous 1919 legislative session, to permit the people of North Dakota to engage, when necessary, in direct democracy. The people used their newfound power just two years later—to put an end to League management of the state industries created in 1919.

When the dust cleared, the people of North Dakota had determined to continue the economic experiment, but to put it into the hands of a different, more conservative, group of men.

The man who replaced Frazier as governor, R.A. Nestos, decided to manage the Bank in “a sane and conservative way” rather than attempt to destroy it. He agreed to give BND a chance to succeed. “It seems to me that it is but right and just and wise to give it a full, fair, and honest trial,” Nestos wrote.

All these maneuvers hurt the Bank both in credibility and in its attractiveness to outside investors, but none of the gambits was able to destroy the Bank or fundamentally emasculate its charter. The people of North Dakota wanted a state bank. They wanted it to be cautious, well-managed, humble and minimally profitable.

The Bank of North Dakota was fortunate to survive its birth pangs and initial growing pains. The provision requiring all local subdivisions (school boards, municipalities, county governments) to deposit their funds in the Bank of North Dakota brought on furious reaction and might, in itself, have caused the people of North Dakota to shut the Bank. The difficulty of selling the necessary bonds was worsened by the collapse of the private Scandinavian American Bank of Fargo, and by the lawsuits brought against the League’s Industrial Program—suits finally settled in the League’s favor by the US Supreme Court in June 1920. The bond boycott promoted by League enemies exacerbated the crisis. A certain amount of favoritism, cronyism and mismanagement in the early days of the Bank’s existence contributed to the view that commercial financial institutions—not state government—should manage the money supply of North Dakota. After an initiated measure freed local subdivisions of the necessity of depositing their funds with the Bank of North Dakota, the cash flow problem worsened.

Banking in Crisis Mode

The difficulties of BND in its first years were just one facet of a larger bank crisis on the northern Great Plains. After North Dakota’s political subdivisions were released from the obligation to deposit their funds in BND in November 1920, the Bank could only remain solvent by calling in funds it had redeposited in commercial banks throughout the state. Many of those banks were unable to meet those demands. The Bank had no choice but to press for repayment, which would lead to the collapse of a number of marginal commercial banks.

Between 1921 (the date of the recall election) and 1924, North Dakota lost almost a third of its commercial banks. Their failure put enormous strain on the state bank. By the end of 1924, BND had more than $1.5 million tied up in closed banks, with little or no hope of recovery. The problems, particular to North Dakota agricultural life, were now compounded by a regional and even national credit crisis.

Defending the Bank of North Dakota

In the face of withering criticism that the Nonpartisan League leaders were dangerous radicals espousing a Bolshevik revolution on the Great Plains, NPL leaders argued that the Bank of North Dakota had been created by legal means (in the state Legislature and at the ballot box) and had successfully withstood court challenges and referenda. If creating a state-owned bank was un-American, what about Alexander Hamilton’s Bank of the United States? Other states had created public corporations: Louisiana owned and operated the Port of New Orleans; King County in the state of Washington owned and operated the Port of Seattle.

The most forceful of the attacks on the NPL were that it was the vanguard of a socialist movement designed to imitate in America the goals and methods of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia; and the charge of disloyalty at a time of international emergency during World War I. The NPL actually endorsed America’s war effort but reserved the right to question both specific actions and the larger war aims of the United States. President Woodrow Wilson met with A.C. Townley, shared many of the League’s concerns about industrial profiteering during war, and encouraged the ND experiment up to a point.

Although the League at different moments imagined a fairly wide number of state-owned economic enterprises, some of them that today seem frivolous, it never intended or suggested a socialist revolution. Bank of North Dakota is one “socialist” legacy of the NPL movement. Important to note however, the farmers of North Dakota were pragmatists, not socialists, and they embraced whatever they thought would actually improve conditions in the farm economy.

Governor Nestos saves the Bank

The new governor Ragnvald Anderson Nestos accepted the voice of the people. They had voted to retire the entire League Industrial Commission, but keep the state enterprises, including the Bank of North Dakota. Governor Nestos hearkened to the voice of the people of North Dakota (keep the bank, manage it better). He therefore determined to administer the Bank “in a sane and conservative way.” He agreed to give the Bank and other state enterprises “a full, fair and honest trial.” To dissolve the state’s hard-won industrial experiment “without a trial…does not seem good sense,” Nestos said.

It was an extraordinary moment for North Dakota. The limited socialist experiment would get its chance to improve economic conditions, but in a chastened, more conservative manner with a more reliable and less “visionary” set of administrators.

Not for the last time, a conservative approach to a radically-born institution probably saved the Bank of North Dakota.

Ragnvald Anderson Nestos was born in Voss, Norway in 1877. One of ten children, he spoke no English when his family immigrated to the United States. Raised by relatives in Buxton, ND, he completed his studies at Mayville State College and the University of North Dakota while homesteading in Pierce County. He established a law office at Minot in 1904.

Hearkening to the voice of the voters of North Dakota, Nestos took an intense personal interest in rehabilitating the Bank of North Dakota. He examined its financial situation and its lending practices and replaced Bank manager F.W. Cathro with C.R. Green of Cavalier, ND. Green was well-respected in North Dakota banking circles.

Nestos was alarmed when he studied the state of the Bank of North Dakota. Perhaps most important, it had been operating at a loss. It had provided loans to farms that could not survive. There had been some favoritism and even cronyism in the loan protocols. Accounting procedures were not sufficiently rigorous.

He discovered that 191 of the 755 farm loans that had been made under League management should never have been approved. Examiners found that “appraisals had been carelessly made and political favoritism had been shown.” Some of the loans had been made in excessive amounts. Some loans had been made to individuals who were not farmers. To make things right, the North Dakota Legislature established a collection branch. Through firmness, patience, and careful use of foreclosure, the Bank was able to recover a substantial amount that had been unwisely distributed.

Under Nestos’ supervision and Green’s conservative management, the Bank now tightened up its farm loan program, and attempted to apply a uniform conservative standard to its loan decisions.

At the same time, the Bank worked carefully with the troubled or failed banks of North Dakota to ease them through a time of great difficulty—in part to serve the people and institutions of the state, in part to recoup money owed to the Bank by small commercial banks across the state.

$2 million in bonds needed to be sold to fund the Bank.

The Bank of North Dakota had a difficult time selling bonds for state industries, partly because banks in Chicago and elsewhere were unsure of the sustainability of the North Dakota enterprises, and partly because of a gathering recession.

On January 7, 1921, the North Dakota Bankers Association offered to help sell North Dakota bonds to eastern financiers, but only with the following conditions:

- That the Bank of North Dakota’s operations be limited to state, state institutions, state industry, farm loans, and farm loan bonds.

- That a new law be passed making commercial banks a legal public depository for the funds of local governments.

- That the ND industrial experiment be limited to the Bank of North Dakota, the experimental mill in Drake, the Grand Forks mill and elevator.

- That the Industrial Commission work with attorneys for the bond purchasers to secure legislation and procedures that would make the bond sales more palatable to out of state investors.

The Industrial Commission rejected the offer. The North Dakota Bankers Association had not made the offer in the spirit of altruism. A severe regional and national commercial bank crisis was wreaking havoc on North Dakota economic life. The association understood that a strong central Bank in North Dakota might be able to shore up faltering commercial banks throughout North Dakota.

Governor Nestos was no shrinking violet. He traveled east in 1923 to sell North Dakota bonds. Before the Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York, Nestos said, “Many of your leaders in industry, commerce and finance seem to have formed the opinion that the farmers of Minnesota and the Dakotas are Socialists, Bolshevists, Communists and Red Radicals politically, ignorant barbarians socially and on the way to the poor house financially, and this opinion is reflected in much of what is being said and printed in your city about the Northwest. The farmers of the Northwest naturally resent the misinterpretation of their political attitude as much as you gentlemen, I am sure, resent the opinion concerning the business men of New York, held in some parts of the West, where a large proportion of the people honestly believe that you are a band of crooks, high binders and financial pirates who operate through Wall Street to deprive the laborers and farmers of the country of that which is their just due.”

Point taken! Nestos’ argument might have come from the pen of William Jennings Bryan as readily as from a conservative Governor of North Dakota.

Governor Sorlie insists on Bank profits.

Governor A.G. Sorlie, elected in 1924, supported the Bank. “Our state bank is an instrument of great potency and value in the establishment of our financial independence as a state. I consider it the greatest step forward of the decade along politico-economic lines.”

Sorlie insisted that the BND show a profit.

“The Bank should stand for much more…. When times of financial stress come to us, such as we are now passing through, the State Bank should stand in much closer relation to the people than that of a mere money-making agency.”

“So far as I am aware, as at presented operated,“ Sorlie wrote, “our State Bank is a mere money-making institution. If that is all it stands for there is no excuse for its existence.”

That was perhaps the most important statement ever uttered about the Bank of North Dakota. North Dakota does not need a state-owned bank that is indistinguishable in mission or financial practices from the many commercial banks of the state. The Bank of North Dakota must have a social and economic mission that provides unique commonwealth value to the citizens of North Dakota.

At the same time, as Governor Sorlie perfectly understood, the Bank must be a sustainable, viable institution operated on sound economic principles and practices, so that it can be sustained over generations and justify its existence to skeptical taxpayers and legislators.

Moreover, its social goals must not be wild-eyed or utopian. The work of the Bank must resonate with the prevailing spirit of the people of North Dakota. That spirit changes over time; the Bank must adjust itself to the mood of the people of North Dakota, and their perceived needs.

In some sense, the Bank of North Dakota is “socialist” in only a very limited sense. At its most conservative the Bank is essentially a commercial bank operating as a state-owned institution. At its most innovative, the Bank is a laboratory for innovative funding of ideas and projects that would be harder to justify from a merely commercial point of view. It has served both functions in its century of operations.

Sorlie died in office in 1928.

The Nonpartisan League Fails

The League failed for a number of reasons. It over-reached both geographically and in mission-creep. There was only one A.C. Townley; nobody has his ability to create enthusiasm.

The forces of reaction in the business community, once they understood the insurrection, proved to be clever and ruthless. And, perhaps most significant of all, World War I changed the whole dynamic of life on the Great Plains. Even those who sympathized with the League’s program were distracted by calls for national unity during the War. The Red Scare that swept the nation was the most severe test of the Bill of Rights in American history.

Against the waves of nationalism, hyper-patriotism, and jingoism that rolled over the continent between 1917-1920, the NPL could not flourish. In 1918, the Bismarck Tribune wrote, “Vote as You Would Shoot! There is only one issue in North Dakota. That issue is LOYALTY.”

The Cataclysm of World War I

Once the United States entered World War I, NPL supporters were accused of stirring domestic waters at a time of international emergency; of impeding recruitment in the US Army; of treason; and of being un-American. The world war probably had more to do with the stalling of the League’s success than any other single factor.

The world war put the Nonpartisan League on the defensive in three distinct ways. First, it sucked the oxygen out of the League’s mission. As the United States mobilized for war, the concerns of “a bunch of disgruntled farmers” in North Dakota were made to seem selfish and parochial. The urgencies of world war were such, League critics argued, that domestic concerns, even legitimate ones, should be postponed until after the successful prosecution of the war. An agrarian uprising during a time of national and international emergency was regarded as disloyal.

Second, although the League’s response to the war was nuanced and never actually disloyal, it was easy enough for the League’s detractors to emphasize every statement by Townley, Lemke, and Joseph Gilbert that was not 100% patriotic and jingoistic, and to quote League leaders out of context to impugn their loyalty. William Lemke was offended by the anti-German pronouncements of men like former President Theodore Roosevelt but, once the United States entered the war, he committed himself unhesitatingly to America’s position. Still, as historian Edward Blackorby writes, “As did many others, he found it easier to feel and express loyalty to the United States than to convince others that he was loyal.” If this was true of Lemke, it was truer still of A.C. Townley. The Bank of North Dakota suffered by association.

Finally, the Nonpartisan League may have collapsed no matter what, but the coming of the war brought boom years to American agriculture. Born of economic desperation, the League ceased to be so attractive when prices rose to historic levels, permitting North Dakota’s farmers to set aside their anger at exploitation by outside interests.

Historian Edward C. Blackorby, who wrote biographies of William Lemke and Usher Burdick, believed that if World War I had not interrupted the movement, the Nonpartisan League would have become a serious national party. At one point, League leader William Lemke began to prepare the League’s farmer-candidate Lynn J. Frazier for the possibility that he might eventually run for the presidency of the United States.

The legacy of the Nonpartisan League.

- North Dakota has the nation’s only state-owned bank, the Bank of North Dakota, located on the east bank of the Missouri River in Bismarck.

- North Dakota has a state mill and elevator in Grand Forks.

- The three-member Industrial Commission was created in the 1919 legislative session to “manage, operate, control and govern all utilities, industries, enterprises and business projects, now or hereafter established, owned, undertaken administered or operated by the State of North Dakota.” The Industrial Commission still exists.

- No matter what politics the commercial or establishment entities of North Dakota pursue, there is always the sense that in the people of North Dakota there is a streak of populist distrust of entities that do not originate in and cannot be controlled by the people of North Dakota.

The Great Depression

The next great crisis in rural life in North Dakota occurred between 1928-1940: the Great Depression coupled with the Dust Bowl, which has been called the greatest manmade environmental disaster in American history.

The Bank of North Dakota played an important role in those desperate years, but this crisis, which extended far beyond the boundaries of North Dakota, brought the federal government into the equation for the first time.

The New Deal and its legacy institutions made the US government rather than the Bank of North Dakota, the primary supplier of rural credit on the Great Plains. In a sense the USDA appropriated many of the programs of the Bank of North Dakota. Imitation is the greatest form of flattery!

During the darkest years of North Dakota history, under the leadership of Governor William L. Langer and the management of his friend Frank Vogel, the Bank of North Dakota did everything it could to keep the state afloat. Local governments, including school districts, often issued warrants against future tax collections as pay for employees. These were essentially post-dated checks. The Bank of North Dakota redeemed these warrants at face value while private banks routinely discounted them, usually by 15 percent.

During the desperate years of the Dust Bowl and Great Depression, Governor Langer and Frank Vogel determined that the Bank of North Dakota would foreclose only on:

- completely abandoned land;

- lands controlled by court officials or heirs of property of mortgaged land that they were not occupying;

- lands not occupied or operated personally by bona fide farmers;

- lands where the mortgagee agreed to the foreclosure in order to clear title.

The “Wild” Bill Langer influence

William L. Langer took an immediate interest in the Bank of North Dakota when he took office as Governor in 1933. He removed the manager, C.F. Mudgett, and replaced him with assistant manager P.H. Butler. Within weeks, Governor Langer had dismissed fully a third of Bank employees. This brought controversy, including on the three-member Industrial Commission, but Langer prevailed.

One Bank employee recalled, “I’ll never forget that day. It must have been 10 or 15 at least walked out of the Bank that morning and didn’t come back. And here comes this crowd of people looking for desks and of course they seated all of them. There weren’t very many that stayed. Some of them stayed a month or two. Some of them stayed till the next payday. Politics blew up in here in North Dakota.”

Governor Langer knew that it would be wrong-headed to forbid all foreclosures on bankrupt farms. Not even a state-owned bank could survive if it protected every debtor in a time of national economic crisis. Many farmers were bankrupt through no fault of their own. Some, however, were bankrupt because they were poor farmers or inept at managing their finances.

Langer and his hand-picked Bank manager Frank Vogel determined to permit foreclosures only on abandoned farms, on lands not occupied by bona fide farmers, on mortgages held by institutions or family members who had no interest in farming, and in situations where the Bank would be doing the lender a service by clearing title.

Langer’s purpose was to save as many authentic family farms as possible, through patience and trust, hope and a fundamental optimism about the integrity of the suffering people of North Dakota.

It is impossible to determine just how many family farms the Bank of North Dakota saved under the humane leadership of Governor William Langer. It was many thousands.

Langer’s farm mortgage policies vindicated the purpose of a state-owned bank and the vision of its idealistic founders formulated in the heady years of the Nonpartisan League’s ascendency. The Bank of North Dakota was dedicated to the welfare of the people of North Dakota, and to the greater social and economic stability of North Dakota. Its mission was social stability not merely profitability. It had the luxury that most commercial banks did not share of being able to let social stability take precedence over the bottom line. The Bank of North Dakota existed not to make money but to serve the people of North Dakota.

At no point in its long history did the Bank perform its mission with more compassion, generosity of spirit, or awareness of its historically unique charter. Some of this was the Bank, much of it Bill Langer. Langer, a conservative but compassionate populist, responded to the greatest crisis in North Dakota history by using every existing state institution—plus a handful of extra-constitutional executive orders—to save North Dakota from collapse and from a general exodus.

The right institution was in the hands of the right leader at the right time.

Langer was no saint. Charges of bribes, extortion, cronyism, and corruption followed him throughout his career. In 1941, the United States Senate was forced to investigate him when it received petitions from North Dakotans arguing that he was unfit for office. The Senate investigation produced 4,000 pages of testimony, much it lurid, and the pertinent Senate committee voted 15:3 not to seat him. Nevertheless, the full Senate voted 52:30 to permit him to take his seat.

One of the charges against Langer was that he had circumvented Bank procedures to permit an outside company, V.W. Brewer of Des Moines, Iowa, to purchase delinquent commercial bank bonds in North Dakota at a discount and then sell them at par to the Bank. If the Bank had done this work itself, it could have saved at least $250,000 in commissions and fees, some said more then $300,000. Still worse, a partner in the Iowa bond firm purchased some Langer family land in North Dakota for $56,800, when even Langer himself admitted under oath that the land was worth less than half that amount. This was the only serious accusation made of Langer’s handling of the Bank of North Dakota. In the end, the scandal hurt Langer more than the Bank.

750,000 mineral acres owned by the state from foreclosed farmland.

During the Great Depression, the Bank was required to foreclose on farmland, even though they allowed most families to stay on the farm. In 1939, the North Dakota Legislature passed a law reserving 5% of the mineral rights on any land the Bank sold. This was increased to 50% in 1941.

An attempt to raise the reserve rate to 100% was struck down by the Supreme Court of North Dakota in 1951. Attempts in the Legislature to permit landowners to purchase their mineral rights from the state have failed. Eventually, 750,000 mineral acres came into state possession. These minerals are held in trust for all of the people of North Dakota. Given the three oil booms in modern North Dakota history, the Bank’s reservation of these mineral rights has proved to be a boon to the state.

For Sale: 6,360 farms

As the Depression began to yield to better times, the Bank of North Dakota attempted to sell back foreclosed farms to their previous owners, even when others were prepared to pay more for the land. As the economy improved, and in conservative reaction to the “New Deal” policies of the Bank during the Depression, the Bank began to sell land to the highest bidder, irrespective of who it was or who had been the previous owner of the acreage. Ironically, this new policy was an indication of a significantly improved North Dakota economy.

In October 1943, the Industrial Commission voted to make state-held lands available to members of the Armed Forces. At a special session of the Legislature in March, 1944, Governor John Moses suggested that these “surplus” lands be made available to veterans on a preferential basis. Although the program was primarily intended to honor returning veterans, these sales to veterans helped the Bank clear its inventory of foreclosed lands. At the beginning of the 1940s, the Bank had 6,360 farms for sale. In 1944, the number had been reduced to 2,554. By 1947, the Bank held only 735 farms. And by 1950, there were only 63 farms left on the Bank’s books. The state’s intention to privatize its holdings had succeeded.

First Transfer to General Fund

The North Dakota Legislature can transfer funds from the Bank’s profits for the state’s general fund and to support special programs. The first such transfer happened in 1945 for $1,725. With every session, Bank leaders work with legislators and state agency stakeholders to set an appropriate portion of the Bank’s profits to return to the state. Since that first transfer in 1945 through 2019, the bank has returned more than $1 billion of its profits for these activities.