The New York Times editorial board finally gets it right about trade in its Sunday editorial, “This Time, Get Global Trade Right.” Some excerpts:

Many Americans have watched their neighbors lose good-paying jobs as their employers sent their livelihoods to China. Over the last 20 years, the United States has lost nearly five million manufacturing jobs.

People in the Midwest, the “rust belt” and elsewhere noticed this a long time ago as people were laid off, “the plant” closed, the downtowns slowly boarded up and the rest of us felt pressure on wages and working hours. How many towns — entire regions of the country — are like this now? Have you even seen Detroit?

“This page has long argued that removing barriers to trade benefits the economy and consumers, and some of those gains can be used to help the minority of people who lose their jobs because of increased imports,” the editors write. “But those gains have not been as widespread as we hoped, and they have not been adequate to assist those who were harmed.”

So acknowledging that our trade deals have hurt the country, they say maybe we could try to do it right with coming agreements. They write:

If done right, these agreements could improve the ground rules of global trade, as even critics of Nafta like Representative Sander Levin, Democrat of Michigan, have argued. They could reduce abuses like sweatshop labor, currency manipulation and the senseless destruction of forests. They could weaken protectionism against American goods and services in countries like Japan, which have sheltered such industries as agriculture and automobiles.

They write that one problem is that these agreements are negotiated of, by and for the giant corporations:

One of the biggest fears of lawmakers and public interest groups is that only a few insiders know what is in these trade agreements, particularly the Pacific pact.

The Obama administration has revealed so few details about the negotiations, even to members of Congress and their staffs, that it is impossible to fully analyze the Pacific partnership. Negotiators have argued that it’s impossible to conduct trade talks in public because opponents to the deal would try to derail them.

But the administration’s rationale for secrecy seems to apply only to the public. Big corporations are playing an active role in shaping the American position because they are on industry advisory committees to the United States trade representative, Michael Froman. By contrast, public interest groups have seats on only a handful of committees that negotiators do not consult closely.

The current trade-negotiation process is a system designed to rig the game for the giant multinationals against everyone else:

That lopsided influence is dangerous, because companies are using trade agreements to get special benefits that they would find much more difficult to get through the standard legislative process. For example, draft chapters from the Pacific agreement that have been leaked in recent months reveal that most countries involved in the talks, except the United States, do not want the agreement to include enforceable environmental standards. Business interests in the United States, which would benefit from weaker rules by placing their operations in countries with lower protections, have aligned themselves with the position of foreign governments. Another chapter, on intellectual property, is said to contain language favorable to the pharmaceutical industry that could make it harder for poor people in countries like Peru to get generic medicines.

These trade agreements place corporate rights over national sovereignty:

Another big issue is whether these trade agreements will give investors unnecessary power to sue foreign governments over policies they dislike, including health and environmental regulations. Philip Morris, for example, is trying to overturn Australian rules that require cigarette packs to be sold only in plain packaging. If these treaties are written too loosely, big banks could use them to challenge new financial regulations or, perhaps, block European lawmakers from enacting a financial-transaction tax.

And they’re asking, like the rest of us are asking, why in the world won’t they do something about currency?

It’s easy to point the finger at Nafta and other trade agreements for job losses, but there is a far bigger culprit: currency manipulation. A 2012 paper from the Peterson Institute for International Economics found that the American trade deficit has increased by up to $500 billion a year and the country has lost up to five million jobs because China, South Korea, Malaysia and other countries have boosted their exports by suppressing the value of their currency.

What So-Called “Free Trade” Agreements Did To The Economy

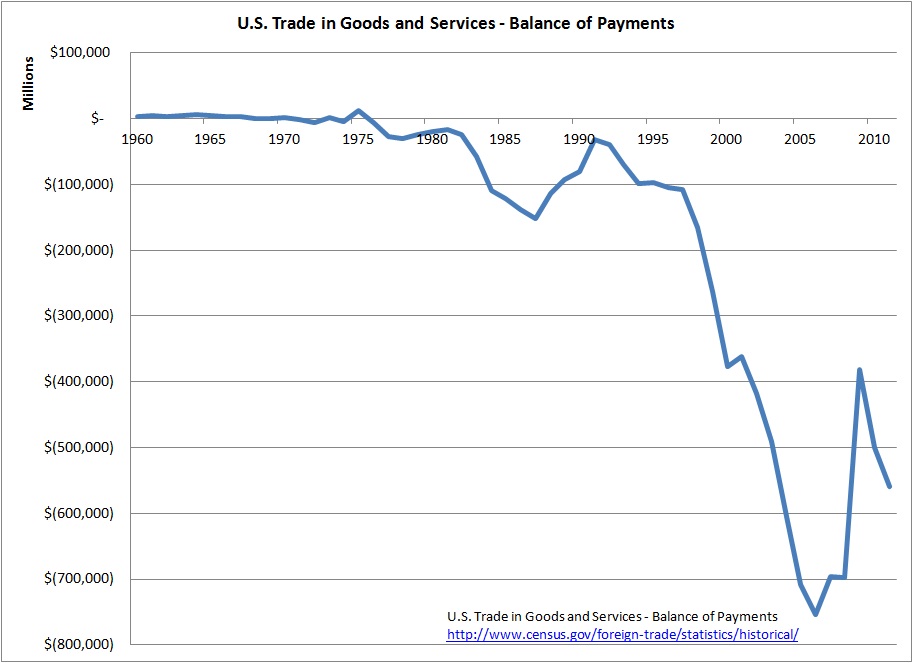

A trade deficit means that we buy more from the rest of the world than we sell to it. This means that jobs making and doing things here migrate to there. Before the mid-70s the United States ran generally balanced trade, with a bias toward surplus. Look at this chart to see what happened, beginning in the ’80s, and then … wham.

Now we have an enormous, humongous, ongoing trade deficit that over the years has added up to trillions and trillions of dollars drained from our economy. We have lost millions and millions of jobs as tens of thousands of factories closed. We have lost entire industries. We are losing our entire middle class to the resulting wage stagnation and inequality.

Here is what happened when the trade deficit took off. First, look at this chart of the “decoupling” of wages with productivity. In other words, as productivity goes up, what happens to the share of those gains that go to labor:

In case you don’t see the correlation, this chart shows both the trade deficit and labor’s share of the benefits of our economy:

Most people understand the damage that so-called “free trade” has done to the economy, much of our country and the middle class. Millions of people have outright lost their jobs because of corporate CEOs who conclude, “It’s cheaper to manufacture where they pay 50 cents an hour and let us pollute all we want.”

Many others have felt the resulting job fear: “If I so much as hint that I want a raise or weekends off they’ll move my job to China, too.” Entire regions have lost their economic base as factories and entire industries closed and moved.

But We Globalized And Expanded Trade

The basic pro-free-trade argument is that all trade is good and these agreements increase trade. NAFTA negotiator Carla Hills, defending NAFTA, says, “our trade with Mexico and Canada has soared 400 percent, and our investment is up fivefold.”

Of course, this is like proudly telling people that the Broncos scored 8 points in the 2014 Super Bowl*. (Hint: the Seahawks scored 43 points.)

Yes, trade is up and exports are up, but imports are up even more, which costs us jobs, factories and industries. What happened was NAFTA “expanded” trade against American workers and our economy, costing about a million jobs and increasing our trade deficit 480 percent. And don’t even ask what happened with our China trade. (Hint: our 2013 trade deficit with China was 318.4 billion dollars.)

How Would The N.Y. Times Fix Trade?

The Times editorial says we should “press countries to stop manipulating their currencies” and “the president also needs to make clear to America’s trading partners that they need to adhere to enforceable labor and environmental regulations.”

OK, but why would the giant multinationals participate? The point of the free-trade regime up to now has been to accomplish the opposite: to free the giants from the pesky laws and regulations imposed by governments, especially from labor and environmental regulations. The negotiations have been a rigged game designed to transfer the wealth of entire nations to a few billionaires (including Chinese billionaires) and giant, multinational corporations. It worked.

Meanwhile … In The L.A. Times

Meanwhile in the Los Angeles Times, representatives George Miller (D-Calif.), Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.) and Louise Slaughter (D-N.Y.) have written an op-ed, “Free trade on steroids: The threat of the Trans-Pacific Partnership,” talk about NAFTA as a “model for additional agreements, and its deeply flawed approach has resulted in the outsourcing of jobs, downward pressure on wages and a meteoric rise in income inequality,” and ask us not to “blindly endorse any more unfair NAFTA-style trade agreements, negotiated behind closed doors, that threaten to sell out American workers, offshore our manufacturing sector and accelerate the downward spiral of wages and benefits.”

In 1993, before NAFTA, the U.S. had a $2.5-billion trade surplus with Mexico and a $29-billion deficit with Canada. By 2012, that had exploded into a combined NAFTA trade deficit of $181 billion. Since NAFTA, more than 845,000 U.S. workers in the manufacturing sector — and this is likely an undercount — have been certified under just one narrow program for trade adjustment assistance. They qualified because they lost their jobs due to increased imports from Canada and Mexico, or the relocation of factories to those nations.

The recent Korea free trade agreement followed the NAFTA model and the results have already proven terrible for American workers:

Obama said it would support “70,000 American jobs from increased goods exports alone.” In reality, U.S. monthly exports to South Korea fell 11% in the pact’s first two years, imports rose and the U.S. trade deficit exploded by 47%. This led to a net loss of tens of thousands of U.S. jobs in this pact’s first two years.

They conclude:

There are many things we can do to enhance our competitiveness with China and in the global economy.

We can invest in our own infrastructure, manufacturing and job training. We can work harder to address issues like currency manipulation, unfair subsidies for state-owned enterprises in other nations and global labor protections. We can enter deals that increase U.S. exports while doing right by our workers and our priorities, and we can address the real foreign policy challenges in Asia with appropriate policies instead of through a commercial agreement that could weaken the United States and its allies.

What we should not do is blindly endorse any more unfair NAFTA-style trade agreements, negotiated behind closed doors, that threaten to sell out American workers, offshore our manufacturing sector and accelerate the downward spiral of wages and benefits.

No New Trade Agreements, Instead Fix The Ones We Have

Of course, as we reach consensus that we got trade wrong, and realize how these “NAFTA-style” agreements have done so much damage to our economy and middle class, doesn’t this mean it is time to back up and renegotiate NAFTA and others?