Above Photo: Photo by Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources

According to a new report by the nonprofit Environmental Working Group, the drinking water of more than a quarter of Americans — some 90 million people — tested positive for a likely carcinogen known as 1,4-dioxane between 2010 and 2015. And public water systems serving more than 7 million people in 27 states have average 1,4-dioxane concentrations that exceed the level US Environmental Protection Agency has said can increase the risk of cancer.

According to a new report, a likely carcinogen was detected in the public water systems serving nearly 90 million Americans.

1,4-dioxane water contamination is linked to several sources, not least of which is the use of the chemical as an industrial solvents to dissolve oily substances. It is also a byproduct of plastic production and manufacturing of other chemicals, and can contaminate drinking water through wastewater discharge from industrial facilities, as well as due to leaching from Superfund and hazardous waste sites.

In addition to being a likely carcinogen (in California, the chemical is listed as a known carcinogen), 1,4-dioxane exposure has also been linked to liver and kidney damage, lung problems, and eye and skin irritation. Some studies also suggest a link between 1,4-dioxane exposure among pregnant women and higher rates of pregnancy loss and complication, though the results were not conclusive.

Manufacturers can alter production methods or treat wastewater to reduce 1,4-dioxane contamination before it enters a community’s water supply. But Tasha Stoiber, a senior scientist with EWG says that once 1,4-dioxane has made it’s way into drinking water, it’s hard to address, adding that common water filters are ineffective, and expensive filters only partly work. “It’s tough,” Stoiber says, “because once this chemical is in ground water or surface water, it’s really difficult to remove.”

And yet, there is no federal legal limit for 1,4-dioxane — the EPA has not regulated the toxin under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

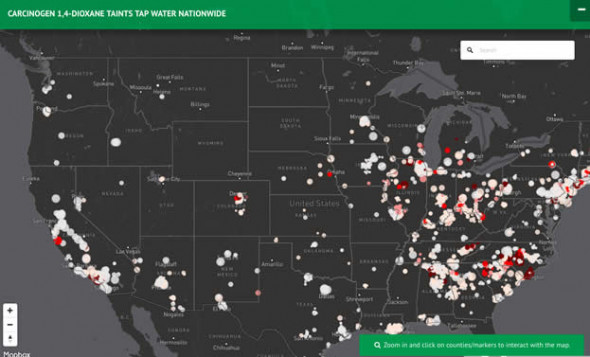

map courtesy EWGClick or tap for an interactive map of 1,4-dioxane-tainted water across the country.

map courtesy EWGClick or tap for an interactive map of 1,4-dioxane-tainted water across the country.

“The EPA can set a legal drinking water standard, a maximum contaminant limit,” Stoiber explains. “They can also limit discharges from some of these industrial sources that are polluting surface water, and they can set regulations for industrial uses under the Toxic Substances Control Act [TSCA].”

Americans are also exposed to 1,4-dioxane through common household products, including cosmetics and cleaning supplies, as well as personal care products like shampoo, body wash, and lotion. Though the chemical is not intentionally added to these products, it can be a byproduct the production process. In addition to regulation by the EPA, consumer and environmental advocates such as EWG would like to see regulation 1,4-dioxane by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which has the authority to limit contamination in household product.

But how likely is federal action? Unfortunately, though 1,4-dioxane was selected as one of the first ten chemicals to be reviewed under the revised federal Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), prospects for action under the current administration aren’t encouraging. Preliminary documents from the TSCA review indicate that not all exposure routes will be considered. Not to mention that President Trump has proposed decreasing funding for both the EPA and the FDA.

What’s more, Trump has nominated industry-insider Michael Dourson to head the EPA’s chemicals and pesticides office. According to the EWG, Dourson has authored two industry-funded papers arguing that exposure to 1,4-dioxane is safe at levels 1,000 times those suggested by the EPA.

“President Trump could not have found a more objectionable nominee to be in charge of safeguarding Americans from dangerous chemicals than Dourson,” Melanie Benesh, an EWG legislative attorney and co-author of the report, says in a statement. “His history of pleasing industry funders with studies that find even the most toxic chemicals to be ‘safe’ makes him uniquely unfit for the job.”

So, for the time being, it seems it may be up to the states. And there’s plenty of improvement to be made in that regard: So far, only a handful of states even have guidelines surrounding 1,4-dioxan exposure, let alone enforceable limits.

There’s also room for private citizens push for action on this hidden threat. “The first step is knowing what’s in your drinking water,” Stoiber says. “That allows the general public to become engaged.” And then, hopefully, to take action.