Above photo: PBS.

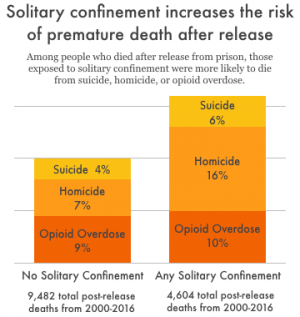

Any amount of time spent in solitary confinement increases the risk of death after release from prison, including deaths by suicide, homicide, and opioid overdose.

A recently published study of people released from North Carolina prisons confirms what many have long suspected: solitary confinement increases the risk of premature death, even after release. Personal stories, like those of Kalief Browder’s isolation and subsequent suicide, are canaries in the coal mine. Underneath seemingly isolated events, researchers now find that solitary confinement is linked to more deaths after release from prison. These preventable deaths aren’t outliers; in the U.S., where the use of solitary confinement is widespread, an estimated 80,000 people are held in some form of isolation on any given day, and in a single year, over 10,000 people were released to the community directly from solitary.

The new study shows that the effects of solitary confinement go well beyond the immediate psychological consequences identified by previous research, like anxiety, depression, and hallucinations. The authors, from the University of North Carolina, Emory University, and the North Carolina Departments of Public Safety and Public Health, find that any amount of time spent in solitary confinement increases the risk of death in the first year after individuals return to the community, including deaths by suicide, homicide, and opioid overdose.

The new study shows that the effects of solitary confinement go well beyond the immediate psychological consequences identified by previous research, like anxiety, depression, and hallucinations. The authors, from the University of North Carolina, Emory University, and the North Carolina Departments of Public Safety and Public Health, find that any amount of time spent in solitary confinement increases the risk of death in the first year after individuals return to the community, including deaths by suicide, homicide, and opioid overdose.

Reentry is tumultuous and challenging to begin with, and the first two weeks after release are among the most difficult. Previous research has shown that, within those first two weeks, the risk of death from drug overdose, cardiovascular disease, homicide, and suicide is elevated. A 2007 study found that the risk of death in these first two weeks can be up to 12 times higher than that of the general population. Building on that study’s findings, this new North Carolina study finds that the experience of any solitary confinement more than doubles the risk of death for people recently released from prison.

The study identifies two additional factors correlated with a heightened risk of death after release: race and the amount (length and frequency) of solitary confinement. All incarcerated people of color are more likely to die within a year of release, and the experience of solitary confinement only amplifies this racial disparity. A previous study found that, compared to their share of the total prison population, Black men and women are overrepresented in solitary confinement, exposing them disproportionately to its harms. And unsurprisingly, more frequent placements in solitary confinement—as well as longer stays

—are associated with worse outcomes across both white and nonwhite populations.

This study adds to the overwhelming body of evidence that solitary confinement causes indelible harm and should be prohibited. But until that happens, the authors recommend that discharge plans and public health systems should consider time spent in solitary confinement as a risk factor to be addressed when people are released from prisons. By considering solitary confinement in discharge plans, reentry programs and professionals could connect people to services after release from incarceration, specifically trauma-informed, community-based substance use and mental health treatment, overdose prevention and harm reduction, and wraparound care and services.

Of course, there is no need to wait until a person is released from prison to address the long-lasting harms of solitary confinement. Programs and professionals working in prisons that use solitary confinement should use this information to provide services that focus on breaking the link between solitary confinement and premature death after release. Correctional systems should not wait to mitigate harms after they have already occurred: Solitary confinement causes far more harm than good and is not a “rehabilitative” process.

Footnotes

- The phrase “solitary confinement” is not used consistently. Some prisons deny that they employ it, instead opting for more administrative-sounding terms, like “Segregated Housing Units” (SHUs) and “restrictive housing.” (See this list from MuckRock for more examples.) While conditions can vary between facilities, for our purposes, “solitary confinement” refers to the practice of segregating individuals from the general population for any reason. Under solitary confinement, individuals are typically forced to remain in small, individual cells for 22 to 24 hours per day with minimal human interaction.

- In 2015, the United Nations revised the Standard Minimum Rules on the Treatment of Prisoners and called for an end to solitary confinement lasting longer than 14 days. Regardless, at least 25 states reported in 2017 that 3,500 people were held in solitary confinement for at least 3 years.

Andrea Fenster is a Policy Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative.