Israel has been stealing nuclear secrets and covertly making bombs since the 1950s. And western governments, including Britain and the US, turn a blind eye. But how can we expect Iran to curb its nuclear ambitions if the Israelis won’t come clean?

Deep beneath desert sands, an embattled Middle Eastern state has built a covert nuclear bomb, using technology and materials provided by friendly powers or stolen by a clandestine network of agents. It is the stuff of pulp thrillers and the sort of narrative often used to characterise the worst fears about the Iranian nuclear programme. In reality, though, neither US nor British intelligence believe Tehran has decided to build a bomb, and Iran‘s atomic projects are under constant international monitoring.

The exotic tale of the bomb hidden in the desert is a true story, though. It’s just one that applies to another country. In an extraordinary feat of subterfuge, Israel managed to assemble an entire underground nuclear arsenal – now estimated at 80 warheads, on a par with India and Pakistan – and even tested a bomb nearly half a century ago, with a minimum of international outcry or even much public awareness of what it was doing.

Despite the fact that the Israel’s nuclear programme has been an open secret since a disgruntled technician, Mordechai Vanunu, blew the whistle on it in 1986, the official Israeli position is still never to confirm or deny its existence.

When the former speaker of the Knesset, Avraham Burg, broke the taboo last month, declaring Israeli possession of both nuclear and chemical weapons and describing the official non-disclosure policy as “outdated and childish” a rightwing group formally called for a police investigation for treason.

Meanwhile, western governments have played along with the policy of “opacity” by avoiding all mention of the issue. In 2009, when a veteran Washington reporter, Helen Thomas, asked Barack Obama in the first month of his presidency if he knew of any country in the Middle East withnuclear weapons, he dodged the trapdoor by saying only that he did not wish to “speculate”.

UK governments have generally followed suit. Asked in the House of Lords in November about Israeli nuclear weapons, Baroness Warsianswered tangentially. “Israel has not declared a nuclear weapons programme. We have regular discussions with the government of Israel on a range of nuclear-related issues,” the minister said. “The government of Israel is in no doubt as to our views. We encourage Israel to become a state party to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty [NPT].”

But through the cracks in this stone wall, more and more details continue to emerge of how Israel built its nuclear weapons from smuggled parts and pilfered technology.

The tale serves as a historical counterpoint to today’s drawn-out struggle over Iran’s nuclear ambitions. The parallels are not exact – Israel, unlike Iran, never signed up to the 1968 NPT so could not violate it. But it almost certainly broke a treaty banning nuclear tests, as well as countless national and international laws restricting the traffic in nuclear materials and technology.

The list of nations that secretly sold Israel the material and expertise to make nuclear warheads, or who turned a blind eye to its theft, include today’s staunchest campaigners against proliferation: the US, France, Germany, Britain and even Norway.

[Whistleblower Mordechai Vanunu. Photograph: AP]

[Whistleblower Mordechai Vanunu. Photograph: AP]

Meanwhile, Israeli agents charged with buying fissile material and state-of-the-art technology found their way into some of the most sensitive industrial establishments in the world. This daring and remarkably successful spy ring, known as Lakam, the Hebrew acronym for the innocuous-sounding Science Liaison Bureau, included such colourful figures as Arnon Milchan, a billionaire Hollywood producer behind such hits as Pretty Woman, LA Confidential and 12 Years a Slave, who finally admitted his role last month.

“Do you know what it’s like to be a twentysomething-year-old kid [and] his country lets him be James Bond? Wow! The action! That was exciting,” he said in an Israeli documentary.

Milchan’s life story is colourful, and unlikely enough to be the subject of one of the blockbusters he bankrolls. In the documentary, Robert de Niro recalls discussing Milchan’s role in the illicit purchase of nuclear-warhead triggers. “At some point I was asking something about that, being friends, but not in an accusatory way. I just wanted to know,” De Niro says. “And he said: yeah I did that. Israel’s my country.”

Milchan was not shy about using Hollywood connections to help his shadowy second career. At one point, he admits in the documentary, he used the lure of a visit to actor Richard Dreyfuss’s home to get a top US nuclear scientist, Arthur Biehl, to join the board of one of his companies.

According to Milchan’s biography, by Israeli journalists Meir Doron and Joseph Gelman, he was recruited in 1965 by Israel’s current president, Shimon Peres, who he met in a Tel Aviv nightclub (called Mandy’s, named after the hostess and owner’s wife Mandy Rice-Davies, freshly notorious for her role in the Profumo sex scandal). Milchan, who then ran the family fertiliser company, never looked back, playing a central role in Israel’s clandestine acquisition programme.

He was responsible for securing vital uranium-enrichment technology, photographing centrifuge blueprints that a German executive had been bribed into temporarily “mislaying” in his kitchen. The same blueprints, belonging to the European uranium enrichment consortium, Urenco, were stolen a second time by a Pakistani employee, Abdul Qadeer Khan, who used them to found his country’s enrichment programme and to set up a global nuclear smuggling business, selling the design to Libya, North Korea and Iran.

For that reason, Israel’s centrifuges are near-identical to Iran’s, a convergence that allowed Israeli to try out a computer worm, codenamed Stuxnet, on its own centrifuges before unleashing it on Iran in 2010.

Arguably, Lakam’s exploits were even more daring than Khan’s. In 1968, it organised the disappearance of an entire freighter full of uranium ore in the middle of the Mediterranean. In what became known as the Plumbat affair, the Israelis used a web of front companies to buy a consignment of uranium oxide, known as yellowcake, in Antwerp. The yellowcake was concealed in drums labelled “plumbat”, a lead derivative, and loaded onto a freighter leased by a phony Liberian company. The sale was camouflaged as a transaction between German and Italian companies with help from German officials, reportedly in return for an Israeli offer to help the Germans with centrifuge technology.

When the ship, the Scheersberg A, docked in Rotterdam, the entire crew was dismissed on the pretext that the vessel had been sold and an Israeli crew took their place. The ship sailed into the Mediterranean where, under Israeli naval guard, the cargo was transferred to another vessel.

US and British documents declassified last year also revealed a previously unknown Israeli purchase of about 100 tons of yellowcake from Argentina in 1963 or 1964, without the safeguards typically used in nuclear transactions to prevent the material being used in weapons.

Israel had few qualms about proliferating nuclear weapons knowhow and materials, giving South Africa’s apartheid regime help in developing its own bomb in the 1970s in return for 600 tons of yellowcake.

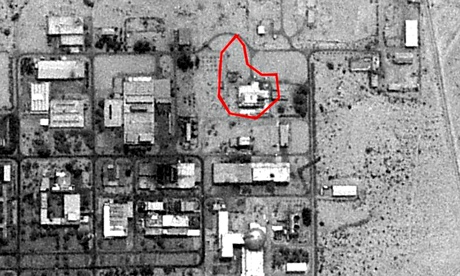

[Pictures of the secret Dimona nuclear reactor in Israel, showing where the plant has allegedly been camouflaged. Photograph: space imaging]

[Pictures of the secret Dimona nuclear reactor in Israel, showing where the plant has allegedly been camouflaged. Photograph: space imaging]

Israel’s nuclear reactor also required deuterium oxide, also known as heavy water, to moderate the fissile reaction. For that, Israel turned to Norway and Britain. In 1959, Israel managed to buy 20 tons of heavy water that Norway had sold to the UK but was surplus to requirements for the British nuclear programme. Both governments were suspicious that the material would be used to make weapons, but decided to look the other way. In documents seen by the BBC in 2005 British officials argued it would be “over-zealous” to impose safeguards. For its part, Norway carried out only one inspection visit, in 1961.

Israel’s nuclear-weapons project could never have got off the ground, though, without an enormous contribution from France. The country that took the toughest line on counter-proliferation when it came to Iran helped lay the foundations of Israel’s nuclear weapons programme, driven by by a sense of guilt over letting Israel down in the 1956 Suez conflict, sympathy from French-Jewish scientists, intelligence-sharing over Algeria and a drive to sell French expertise and abroad.

“There was a tendency to try to export and there was a general feeling of support for Israel,” Andre Finkelstein, a former deputy commissioner at France’s Atomic Energy Commissariat and deputy director general at the International Atomic Energy Agency, told Avner Cohen, an Israeli-American nuclear historian.

France’s first reactor went critical as early as 1948 but the decision to build nuclear weapons seems to have been taken in 1954, after Pierre Mendès France made his first trip to Washington as president of the council of ministers of the chaotic Fourth Republic. On the way back he told an aide: “It’s exactly like a meeting of gangsters. Everyone is putting his gun on the table, if you have no gun you are nobody. So we must have a nuclear programme.”

Mendès France gave the order to start building bombs in December 1954. And as it built its arsenal, Paris solds material assistance to other aspiring weapons states, not just Israel.

“[T]his went on for many, many years until we did some stupid exports, including Iraq and the reprocessing plant in Pakistan, which was crazy,” Finkelstein recalled in an interview that can now be read in a collection of Cohen’s papers at the Wilson Centre thinktank in Washington. “We have been the most irresponsible country on nonproliferation.”

In Dimona, French engineers poured in to help build Israel a nuclear reactor and a far more secret reprocessing plant capable of separating plutonium from spent reactor fuel. This was the real giveaway that Israel’s nuclear programme was aimed at producing weapons.

By the end of the 50s, there were 2,500 French citizens living in Dimona, transforming it from a village to a cosmopolitan town, complete with French lycées and streets full of Renaults, and yet the whole endeavour was conducted under a thick veil of secrecy. The American investigative journalist Seymour Hersh wrote in his book The Samson Option: “French workers at Dimona were forbidden to write directly to relatives and friends in France and elsewhere, but sent mail to a phony post-office box in Latin America.”

The British were kept out of the loop, being told at different times that the huge construction site was a desert grasslands research institute and a manganese processing plant. The Americans, also kept in the dark by both Israel and France, flew U2 spy planes over Dimona in an attempt to find out what they were up to.

The Israelis admitted to having a reactor but insisted it was for entirely peaceful purposes. The spent fuel was sent to France for reprocessing, they claimed, even providing film footage of it being supposedly being loaded onto French freighters. Throughout the 60s it flatly denied the existence of the underground reprocessing plant in Dimona that was churning out plutonium for bombs.

[Producer Arnon Milchan with Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie at the premiere of Mr and Mrs Smith. Photograph: L Cohen]

[Producer Arnon Milchan with Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie at the premiere of Mr and Mrs Smith. Photograph: L Cohen]

Israel refused to countenance visits by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), so in the early 1960s President Kennedy demanded they accept American inspectors. US physicists were dispatched to Dimona but were given the run-around from the start. Visits were never twice-yearly as had been agreed with Kennedy and were subject to repeated postponements. The US physicists sent to Dimona were not allowed to bring their own equipment or collect samples. The lead American inspector, Floyd Culler, an expert on plutonium extraction, noted in his reports that there were newly plastered and painted walls in one of the buildings. It turned out that before each American visit, the Israelis had built false walls around the row of lifts that descended six levels to the subterranean reprocessing plant.

As more and more evidence of Israel’s weapons programme emerged, the US role progressed from unwitting dupe to reluctant accomplice. In 1968 the CIA director Richard Helms told President Johnson that Israel had indeed managed to build nuclear weapons and that its air force had conducted sorties to practise dropping them.

The timing could not have been worse. The NPT, intended to prevent too many nuclear genies from escaping from their bottles, had just been drawn up and if news broke that one of the supposedly non-nuclear-weapons states had secretly made its own bomb, it would have become a dead letter that many countries, especially Arab states, would refuse to sign.

The Johnson White House decided to say nothing, and the decision was formalised at a 1969 meeting between Richard Nixon and Golda Meir, at which the US president agreed to not to pressure Israel into signing the NPT, while the Israeli prime minister agreed her country would not be the first to “introduce” nuclear weapons into the Middle East and not do anything to make their existence public.

In fact, US involvement went deeper than mere silence. At a meeting in 1976 that has only recently become public knowledge, the CIA deputy director Carl Duckett informed a dozen officials from the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission that the agency suspected some of the fissile fuel in Israel’s bombs was weapons-grade uranium stolen under America’s nose from a processing plant in Pennsylvania.

Not only was an alarming amount of fissile material going missing at the company, Nuclear Materials and Equipment Corporation (Numec), but it had been visited by a veritable who’s-who of Israeli intelligence, including Rafael Eitan, described by the firm as an Israeli defence ministry “chemist”, but, in fact, a top Mossad operative who went on to head Lakam.

“It was a shock. Everyody was open-mouthed,” recalls Victor Gilinsky, who was one of the American nuclear officials briefed by Duckett. “It was one of the most glaring cases of diverted nuclear material but the consequences appeared so awful for the people involved and for the US than nobody really wanted to find out what was going on.”

The investigation was shelved and no charges were made.

A few years later, on 22 September 1979, a US satellite, Vela 6911, detected the double-flash typical of a nuclear weapon test off the coast of South Africa. Leonard Weiss, a mathematician and an expert on nuclear proliferation, was working as a Senate advisor at the time and after being briefed on the incident by US intelligence agencies and the country’s nuclear weapons laboratories, he became convinced a nuclear test, in contravention to the Limited Test Ban Treaty, had taken place.

It was only after both the Carter and then the Reagan administrations attempted to gag him on the incident and tried to whitewash it with an unconvincing panel of enquiry, that it dawned on Weiss that it was the Israelis, rather than the South Africans, who had carried out the detonation.

“I was told it would create a very serious foreign policy issue for the US, if I said it was a test. Someone had let something off that US didn’t want anyone to know about,” says Weiss.

Israeli sources told Hersh the flash picked up by the Vela satellite was actually the third of a series of Indian Ocean nuclear tests that Israel conducted in cooperation with South Africa.

“It was a fuck-up,” one source told him. “There was a storm and we figured it would block Vela, but there was a gap in the weather – a window – and Vela got blinded by the flash.”

The US policy of silence continues to this day, even though Israel appears to be continuing to trade on the nuclear black market, albeit at much reduced volumes. In a paper on the illegal trade in nuclear material and technology published in October, the Washington-based Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS) noted: “Under US pressure in the 1980s and early 1990s, Israel … decided to largely stop its illicit procurement for its nuclear weapons programme. Today, there is evidence that Israel may still make occasional illicit procurements – US sting operations and legal cases show this.”

Avner Cohen, the author of two books on Israel’s bomb, said that policy of opacity in both Israel and in Washington is kept in place now largely by inertia. “At the political level, no one wants to deal with it for fear of opening a Pandora’s box. It has in many ways become a burden for the US, but people in Washington, all the way up to Obama will not touch it, because of the fear it could compromise the very basis of the Israeli-US understanding.”

In the Arab world and beyond, there is growing impatience with the skewed nuclear status quo. Egypt in particular has threatened to walk out of the NPT unless there is progress towards creating a nuclear-free zone in the Middle East. The western powers promised to stage a conference on the proposal in 2012 but it was called off, largely at America’s behest, to reduce the pressure on Israel to attend and declare its nuclear arsenal.

“Somehow the kabuki goes on,” Weiss says. “If it is admitted Israel has nuclear weapons at least you can have an honest discussion. It seems to me it’s very difficult to get a resolution of the Iran issue without being honest about that.”