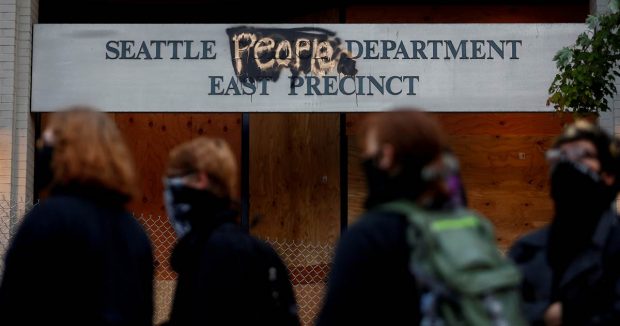

Above photo: People stand in front of the Seattle Police Department’s East Precinct sign in the “Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone” while continuing to demonstrate against racial inequality and call for the defunding of Seattle police in Seattle on Tuesday, June 9, 2020. Lindsey Wasson for Reuters.

Spontaneous urban uprisings have a soul of their own.

To guide one through a decision-making process is very difficult but not impossible.

Nationwide demonstrations, mobilized around the Black Lives Matter movement’s response to the killing of George Floyd, were held in all fifty states and in 5,000 cities. Rallies were held in public squares and larger cities saw their freeways and bridges blocked. Only a few cities ( Richmond, Va.; Philadelphia; Oakland, CA, and New York City ) experienced occupations of public space. None of them were sustained for long, except Seattle, which went on for a month.

When the police abandoned their undamaged East Precinct Police Station, because they did not want demonstrations on the streets bordering it, the demonstrators moved into those streets and declared it under the people’s control. Initially, the most vocal protest leaders declared it an “autonomous” zone. That caught everyone’s attention. Seattle’s occupied three-block-long street, located in a neighborhood business and residential area, received extensive national coverage.

The three largest news channels, CNN, MSNBC, and FOX News, repeatedly covered the occupation. Leaders from the local BLM group proclaimed the occupation as CHOP (Capitol Hill Organized Protest). Often TV reporters just got the facts wrong. One Fox news analyst described the demonstrators’ autonomous zone as an immense six-block radius area and the CHOP occupiers were terrorists bent on destroying Seattle. The other two stations saw them demonstrators accurately as a mixture of curious local residents, racial justice advocates, and peaceful libertarians.

The Seattle independent journalist Omari Salisbury live-streamed reported from the CHOP during the entire occupation. In an NPR interview he spoke of lost opportunities:

…a lot of people who just really, just want to be heard in a peaceful way and in a peaceful capacity. But there was nobody, with this national and international spotlight, who could just emerge here, and who could just speak with a little bit of humanity, to the people in the street and understand it, and also build a bridge down the City Hall, and everything else.

Another independent Seattle journalist, Kevin Schofield, wrote of his disappointment with the CHOP experience in his Tragedy Of Errors piece. He faulted everyone involved. Mayor Jenny Durkan stumbled through experimenting with new approaches without any clear path forward. Seattle Police Chief Carmen Best, the city’s first female black to hold that position, she issued a ban on the use of tear gas by patrol officers, only to reauthorize it less than 48 hours after her ban.

Schofield, who also criticized the city government and the protestors. He claimed that politicians turned CHOP into political theater, cranking out council bills supposedly responding to protesters’ demands. While the demonstrators who appeared to be leading the occupation failed to form an “Occupy Seattle” organization to demand that the city address structural racism and over-policing. Instead, he saw CHOP becoming an “Occupy Woodstock” experiment in participatory democracy. Not having a clearly identified leadership allowed the police chief to honestly say she didn’t know who she could negotiate with from CHOP.

Both journalists said, in so many words, there was no organization providing effective leadership to the rebellion. Although CHOP provided open forums allowed for group discussions, no sustainable organized decision-making apparatus was created. The major groups in the occupation seemed to be primarily concerned with keeping the peace within their controlled area.

It is not surprising that a single guiding organization did not develop. There were probably individuals in CHOP who tried their hardest to create one. However, the social dynamics within urban populist rebellions and the political powers outside them make it difficult to create an organization that can sustain the occupation of open public space. That hurdle was also present in the thirty cities in 2011 when the Occupy Wall Street movement occupied public plazas or parks for indefinite periods of time.

The most famous being the two-month-long occupation of New York’s Zuccotti Park in the financial district in Lower Manhattan. At that same time, Seattle’s Occupy Wall Street moved around to three different occupation sites. First starting at the Westlake Mall in the core of downtown, then moving to the City Hall Plaza, at the invitation of the Mayor as they were being forcibly removed from the Westlake location. Seattle’s OWS group finally decided to move to the Seattle Central Community College (SCCC) campus and stayed for a month, until they were forced to leave.

The OWS occupations did develop organized efforts through their “general assemblies”, which allowed for an orderly and democratic discussion of how their occupation should function. However, different political philosophies competed for control, which hindered the development of an effective organization. The same struggle became apparent at Seattle’s CHOP when no single group could claim to speak for it.

Three main philosophical tendencies appear to be jostling for control. A Libertarian anarchist approach advocated direct action, direct democracy, and a rejection of existing political institutions. Another philosophy fits more into a socialist paradigm of focusing on the larger societal inequities and how the occupation should address them. And then there was a pragmatic philosophy that advocated practical immediate political gains to allow for further organizing opportunities down the road. Although each philosophy had a different priority, there was enough overlap to allow for some coherent and coordinated action, if there had been an identifiable objective, they could all agree to.

A bigger barrier to success than competing philosophies is the ambiguity of defining an objective when open public space is being occupied in possible perpetuity. Who controls the space and who has access to it? If other citizens, who do not have political power inside the occupied area or outside of it, have had their usual access to this occupied land be compromised, then as a local community they will likely oppose it. That gives the authorities the justification for disbanding the occupants.

However, there are examples of where occupying a piece of land has resulted in success. It involves taking control of real property and that property is not critical to the needs of another community. It literally moves a protesting groups’ objective from being against a number of social and political existing conditions to wanting a real physical object in order to better mobilize a community to change those conditions. It moves from controlling an open public space, which may have little or no connection to directly addressing their grievances, to controlling a particular building to help them pursue those grievances. By making that change, leadership and an organization are required to focus on a finite, measurable, and achievable goal.

Seattle’s history provides three specific examples: Daybreak Star Cultural Center, El Centro de la Raza, and the Northwest African American Museum (NAAM). In each instance, a discriminated minority community, Native American, Latino/Chicano, and African American, successfully occupied a public building that eventually resulted in it being turned over to that community’s legal control, allowing them to serve their community’s needs. All three occupied an unused building that no other community sought to use. Their length of occupation varied. Daybreak had multiple short-term occupations, El Centro was occupied for three months, and NAAM took eight years of occupation and negotiation. All efforts were led by a single organization with recognized leadership and overarching philosophy of focusing on a single objective — obtaining control of a building.

Each effort was initially met by local government resistance, and in some instances police force was used. However, by having an organization with supporters largely in agreement on tactics, they were able to put constant political pressure on the authorities. This involved organizing rallies, marches and sit-ins within government buildings. All this activity was to gain positive media coverage on the reasonableness of their demands to provide for the practical needs of their community. As a result, the authorities recognized that they could and had to negotiate a solution that would be acceptable to the occupiers.

These examples show how an occupation focusing on a singular objective means having a clearly defined measurement for success such as acquiring a physical resource for helping meet the needs of a discriminated community. Nevertheless, occupying open public spaces have successfully captured national attention on existing police brutality and systemic racism in the application of law enforcement. That attention is now resulting in cities being pressured to move funds from militarized police forces, whose culture has been largely limited to “catching criminals and putting them in jail,” to a more holistic, humanistic approach that can earn the trust and respect of communities they patrol.

But for protestors to simply draw out an occupation with no clear end in sight, actually diffuses their message to address major issues. This occurs because citizens who are occupying public spaces do not have the resources to create a sustainable safe environment. Lacking one swing open a wide door for critics to get media coverage by highlighting any and all of the shortcomings that result from that situation. Consequently, the groups’ initial meaningful message can be diminished in the media.

The path toward a successful occupation tactic, if it is not to obtain a building, is to pull out before things fall apart. By leaving voluntarily rather than being pushed out, leaves the public remembering the protestor’s message and not on the problems created by trying to create an “autonomous” zone in an open public space.

An organization that has the respect and trust of the larger protestor community, is required to lead them down a path of planned actions with clear objectives. Such an organization also needs resources and internal discipline from its members and supporters if a plan executes a withdrawal.

Looking back again on the CHOP experience reveals how difficult that task is when an open public space if being occupied by a diverse assortment of communities and philosophies. There were probably only five existing organizations that might have been able to pull off that effort. I do not mention their leaders by name because I want to focus on the organizations, not on personalities. However, it is very likely that all of these organizations had members who were involved in or at least supportive of CHOP. The hyperlinks to each organization provide additional information.

The local King County Democratic Party was the largest and best-organized group available to influence CHOP. It has identifiable members in each neighborhood and an internet communication network for being in touch with them. It also has a philosophy that is compatible with larger social justice objectives and more immediate pragmatic solutions. It was practically invisible at CHOP as an active organization. There were most certainly individual members of it at CHOP, maybe in leadership roles, but as an organization, it was not a force. The Democratic Party generally cannot respond quickly to events. Its membership is not prone to direct actions, like occupations. Additionally, the DP is part of the political system with members in elected office. Those public officials have to be accountable to their constituents, many of whom may oppose occupations. As a result, the DP is rarely a major player in demonstrations that form from a populist uprising.

The second-best organized group was the local chapter of the national Socialist Alternative Party, which has far less than a tenth of Seattle’s Democratic Party membership. It is highly organized but with a much narrower philosophical bandwidth. Their SA member on the Seattle city council was at the demonstrations and even managed to convince a large contingency of CHOP occupants to march down to city hall. She let them inside, after that building had officially closed, and held an impromptu rally. But SA had no direct role in how CHOP’s decision making was occurring. And although it is more nimble than the DP in making decisions, it may lack the bandwidth to engage in negotiations that diverge too far from their philosophy. As their website says SA is in the “revolutionary tradition of the leaders of the Russian Revolution, Lenin, and Trotsky from which we draw inspiration.”

The next three organizations are truly grassroots-based but also less organized with fewer resources than the first two mentioned.

The Seattle People’s Party, formed in 2016, describes itself as a “community-centered grassroots political party led by and accountable to the people most requiring access and equity in the City of Seattle.” They ran an SPP member for Seattle Mayor, narrowly missing the general election by 1,100 votes. In that effort, they mobilized over 1,000 volunteers and knocked on 22,000 doors. They have the membership muscle to run political campaigns. Their most visible board member, who ran for mayor, often was a media commentator on the significance of CHOP. In an NPR interview, she emphasized the importance of not criticizing other protestors, no matter what direct action strategies they employed. SPP was not mentioned in the media playing any role in shaping CHOP and their presence was not visibly prominent within the occupation zone. While SPP would certainly have the respect of the CHOP occupants, it was not apparent that it tried to influence the occupants to leave at any time.

The Seattle Democratic Socialists of America describe themselves as anti-capitalists who believe that both the economy and society should be run democratically. They state, “We are a political and activist organization, not a party.” They have a website, but like SA’s website, no local board members are identified. DSA has posted Black Lives Matter issues but nothing about CHOP. Like SPP, they do not appear as an organization having a role in guiding CHOP’s future nor do they proffer on what it should be. However, they did devote space on their website to an event hosted by the Seattle Black Collective Voice, which has grown out of the local Black Lives Matter movement.

Which brings us to the last of the five groups, and probably the most important: Black Lives Matter Seattle-King County (BLMSKC ). Their core activists and organizers consist of a “group of Black and other people of color focused on dismantling anti-black systems and policies of oppression.” The local group tweeted that “CHOP started in response to the need for safety of Black bodies from police and racial violence, and the demand for authentic accountability and change.” They also posted their response to being asked to help shut down CHOP: “you can’t shut down human needs or the people who demand them — you can only meet or exceed them.”

A BLM spokesperson declared soon after the start of the occupation, that the Capitol Hill area was not an Autonomous Zone, but an Organizing Protest, hence it went from CHAZ to CHOP. Later, a new group appeared, the Seattle Black Collective Voice, and their spokesperson said, “It’s the will of the people,” when asked how long CHOP residents plan to camp out. The local BLM may have been the driving force behind CHOP and Seattle’s demonstrations in general, but it did not appear that those occupying CHOP were about to relinquish their freedom to protest as they best saw fit. The libertarian philosophy was evident in not wanting to be subject to any organization’s authority.

This brief review of relevant organizations shows how none of them, however big or organized, sympathetic, or active, could determine the fate of CHOP. Spontaneous urban uprisings have a soul of their own. To guide one through a decision-making process to reach a near consensus is practically impossible. That is particularly true if it was not organized by a single group and does not have a measurable objective.

Despite the CHOP zone no longer being an entity, the occupant’s most publicized objective to significantly defund Seattle’s police department appears to have been achieved. While the mayor responded with a minimal 5% cut in the police budget, a majority of the Seattle City Council members agreed with advocates to defund the Police Department by 50% and reallocate the dollars to other community needs. Although the details and execution of that reduction must still be defined. While CHOP failed to be permanent, it did put reforming the police department into overdrive. However, for there to be a lasting success, those five organizations will need to work together to achieve that end goal.

Nick Licata is author of Becoming A Citizen Activist, and has served 5 terms on the Seattle City Council, named progressive municipal official of the year by The Nation, and is founding board chair of Local Progress, a national network of 1,000 progressive municipal officials.

Subscribe to Licata’s newsletter Urban Politics