The left should welcome the rise of social movements as union influence wanes. But protesters must form alliances if they are to be effective

So much for a winter of discontent. The etiolated state of the British left in 2013 gives us no right to expect any such climax. All the seasonal metaphors – red-hot autumns, summers of rage, even democratic springs – have eluded us.

Why is the landscape so bleak? In 2011, things looked different. The election of a Tory-led government in the UK and a spate of Tea Party Republicans in the US initiated a sequence of austerity programmes – prompting direct conflicts between governments and organised workers. And this seemed to fuse with a heterogeneous series of global struggles, from Middle East revolutions to strike action in Greece to the indignadosin Spain and the Occupy movement.

The militancy was short-lived. As far as the UK goes, the strikes of 2011 look like a blip. In 2012, the days lost to strike action fell from 1.4m to250,000, one of the lowest rates of action on record. As for the US, the disputes such as the one in Wisconsin were far more politically salient than anything else. The rate of industrial action in the leading capitalist economies since the credit crunch has not been merely low: it has been at historic lows. The disruption to the flow of profit is minimal: less than0.005% of working time is lost to strike action each year in the US, for example. No wonder corporate profits have been at historic highs. Meanwhile, in the same economies, the movements largely collapsed or deflated, or were swept up by violent police intervention.

There are structural tendencies at work here. There is the secular disengagement of masses from organised politics, whether party membership or, increasingly, voting. The old institutional bases of radicalism have been demolished. There is the long-term decline in union density and a decline in the frequency of industrial action. Restrictive labour laws and the growing bureaucratisation of unions means strikes occur more slowly and less often. Industrial action is “tertiarised”, taking place mainly in the service sector, and mostly in the public sector.

Take a simple contrast. The peak years of the winter of discontent saw strikes take place in large, strategically important industries. They were often led by rank-and-file movements, acting against the union leaderships. They shook governments, and made the social contract of its day – a pay restraint agreement leading to real cuts in living standards – unworkable. Some 39m working days were lost to strike action in 1978 and again in 1979. In 2011, the strikes were led by union bureaucracies, they took place largely in the far less central public sector, they each lasted one day, and their main use was as a negotiating lever to obtain a slightly less worse pensions deal.

The growth of social movements

However, there is one notable trend that stands apart from the general picture of decline that I noted above. That is the ongoing rise of protest and social movements. The proportion of Britons who have taken part in some form of protest action against the government has more or less consistently risen, almost doubling between 1986 and 2003. This is part of a global trend registered by the World Values Survey (data here).

[Indignados protests in Barcelona, May 2012. Photograph: Emilio Morenatti/AP]

[Indignados protests in Barcelona, May 2012. Photograph: Emilio Morenatti/AP]

Aloof from official politics, non-party-aligned and sometimes distant from trade unionism, such movements reflect the growing prominence of issues and forms of profound social conflict that emerge outside the workplace. Capitalism has demonstrated a tendency to politicise ever-growing areas of life, from the environment to the genetic code, and the profusion of “new social movements” since the 1960s reflects this.

This is something that filled conservatives with horror, and led to the “crisis of democracy” thesis according to which overactive citizens were overloading governments with demands and causing their breakdown. There was also some standoffishness in parts of the left, at least insofar as these were seen as displacing the central emphasis on class struggle. But the rise of the social movement is something the left should welcome. As Colin Barker has argued, the new movements “expanded the very meaning and the agenda of human emancipation”.

Indeed, the movements of anticapitalists and alter-globalists, and more recently, the indignados and occupiers, reflect the long legacy of this in their attempts to construct a complex unity, a unity in difference. At their best, they sought to fuse together a many-headed hydra of anticapitalism, trade unionism, environmentalism, and so on; to build a coalition, a multitude which actively took into account the interests of women, black people, LGBTQ and disabled people, rather than treating them as an afterthought.

However, to leave it at that is to risk idealising social movements, or treating them almost as a panacea. As the late sociologist Charles Tilly pointed out, nothing was more common at the turn of the 21st century than to hear a social movement rhetorically summoned up as the solution to any given issue: whether an anti-regime struggle in Zimbabwe, a debt relief campaign in Europe, a diarrhoea control effort in Bangladesh or labour struggles in Canada. Is this a tribute to the versatility of the social movement form or, in a malign twist on the same point, a mark of the basic emptiness of the form? Is the call for a social movement perhaps a bit like saying “just do something”? One way to answer this is to look at a concrete example and see what distinguishes it.

The US civil rights movement as a model

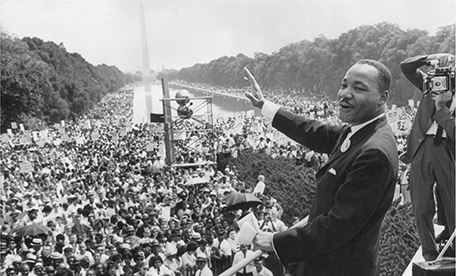

[Martin Luther King Jr during the 1963 march on Washington. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

[Martin Luther King Jr during the 1963 march on Washington. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

The archetypal social movement, which inspired many students of social movements in the coming years, is the great struggle for civil rights in the US, most iconically represented in the March on Washington in August 1963. This exhibited the three characteristics of the modern social movement form, identified by Tilly: a public campaign making claims on target authorities; the deployment of an array of tactics and strategies, the “social movement repertoire”; and displays of popular legitimacy, of commitment, rectitude and of numerousness.

Stretching from 1954 to 1968, this complex movement united diverse agencies, such as the NAACP, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Students’ Non-Violent Co-ordinating Committee and even (to the FBI’s horror) the Communist party. And it faced down an array of opponents – not only southern state authorities and their parapolitical allies (such as the Klu Klux Klan); not only Washington DC, but also the social movements that emerged to contest civil rights, such as the White Citizens’ Council.

This was achieved through an ensemble of strategies, from wrangling in the courts up to and including the supreme court, to consumer boycotts, business lobbying, mass protests, strikes and civil disobedience. In these strategies, they exercised both communicative power, in the form of “consciousness raising”, and structural power – or what Frances Fox Piven would call “disruptive power”, the ability to stop co-operating in the reproduction of the social system, and even actively obstruct it.

Notably, there was no single overarching infrastructure or leadership – yet both infrastructure and leadership were central to the movement’s success. And these infrastructures often included elements – parties, unions, churches, civil society organisations – which pre-dated the civil rights struggle itself. They provided forms of sociality, points of intersection where dispersed populations mingled, forums in which rival strategies and tendencies could be contested, and vehicles through which they could be pursued.

When protest movements die

What happens when you degrade and diminish that infrastructure almost to nothing, while wounds of injustice still fester? What happens when the major institutions through which popular political action takes place are either wholly co-opted or die? What happens is something like the student movement against tuition fees in Britain in late 2010. This movement sprang up almost spontaneously – not entirely, as the vitiated democratic structures of the NUS still played a part, if a limited one. It drew in tens of thousands of young people, linked by little more than social media and sometimes their own milieus, but with no relation to institutional politics. It threw the authorities, put the government briefly on the back foot, and provoked frenzied horsebacked repression. And then it died once the bill to raise tuition fees was passed, leaving some minimal, ad hoc infrastructures behind. The grim echo of this defeat were the riots in the summer of 2011.

What happens, alternatively, is something like Live 8 or the Big If campaigns. Neoliberalism, hollowing out democratic institutions, encourages instead the proliferation of new political forms modelled on capitalist businesses: NGOs, for example. NGOs like lobbies and charities can be democratic organisations, of course, but generally are narrow bureaucracies modelled on capitalist enterprises. As a result, those well-meaning organisations attempting to achieve limited goals toward debt-reduction or environmental protection might occasionally need to simulate democratic legitimacy. To this end, they can mimic the basic format of social movements, usually emphasising the “consciousness-raising” aspect of such activity. A series of communicative techniques involving celebrity are deployed, building up to a “big day”: a rock festival or televised spectacle, a moment of ecstatic unity. Some “achievements” are listed – failure is rarely acknowledged – and the people go home, apparently satisfied. But little changes. Rarely are more people actually engaged in politics as a result of such campaigns.

[Students protest tuition fee increases in Montreal in 2012. Photograph: Steeve Duguay/AFP/Getty Images]

[Students protest tuition fee increases in Montreal in 2012. Photograph: Steeve Duguay/AFP/Getty Images]

These are the two extremes of a Janus-faced problem: spontaneous but unsustained radicalism on the one side, hypertrophied bureaucratism on the other. The problem is a lack of democracy. The problem is a lack of self-organisation. To see how it can be different, consider another, more contemporary example of a social movement.

Lessons from Quebec

In Quebec in 2011, the students fought an authoritarian neoliberal government, determined to impose tuition fee rises, and won handsomely. They used a combination of tactics, from forms of direct democratic organisation on campuses, to direct action on the streets. They solicited union solidarity, and lent their support to striking workers. They sought an expansive unity, one based on class as the shared ground of experience on which diverse millions could unite. Though they sought popular legitimacy, they did not defer to the media, and refused to bow to “law and order” when the Liberal government cracked down on the right to protest. They had a communicative strategy: it just wasn’t one aimed at winning over elites. And, though their approach was hardly parliamentarist, many students lent tactical support to the left party Québec Solidaire in the federal elections, which helped shift the balance of forces in parliament to the left; more so than the far-from-impressive vote for the winning Quebec nationalist party would have. The incoming government, after months of growing militancy, repealed the tuition fee rises and pledged to overturn the repressive anti-protest laws.

All such victories are necessarily partial and provisional. But this was certainly a success, the only serious setback for an austerity programme since 2010. And it was crucially made possible by the existence of long traditions of grassroots organising inherited from the “quiet revolution” of the 1960s, as well as another tradition of social democratic left-nationalism in Quebec, which has not yet been fully undermined by neoliberalism.

Whether we scry into the past, or take a longing look abroad, the answer seems to be the same: successful social movements thrive and avoid the limits of spontaneity and bureaucratic routine on the basis of tenaciously constructed infrastructures, unions, parties, organisations of political combat linked to grassroots democracy.

This would seem to be a crucial lesson today when any anti-austerity campaign in the UK will look like some form of social movement: a “system of alliances”, in Antonio Gramsci’s term, in which the quite heterogenous forces affected by austerity are united in an array of strategies and organisations.

Such a movement will have to proactively build, as a condition of its own success, precisely the forms of popular self-organisation that have been depleted in the neoliberal era. It will have to be a movement of reconstruction as well as resistance.