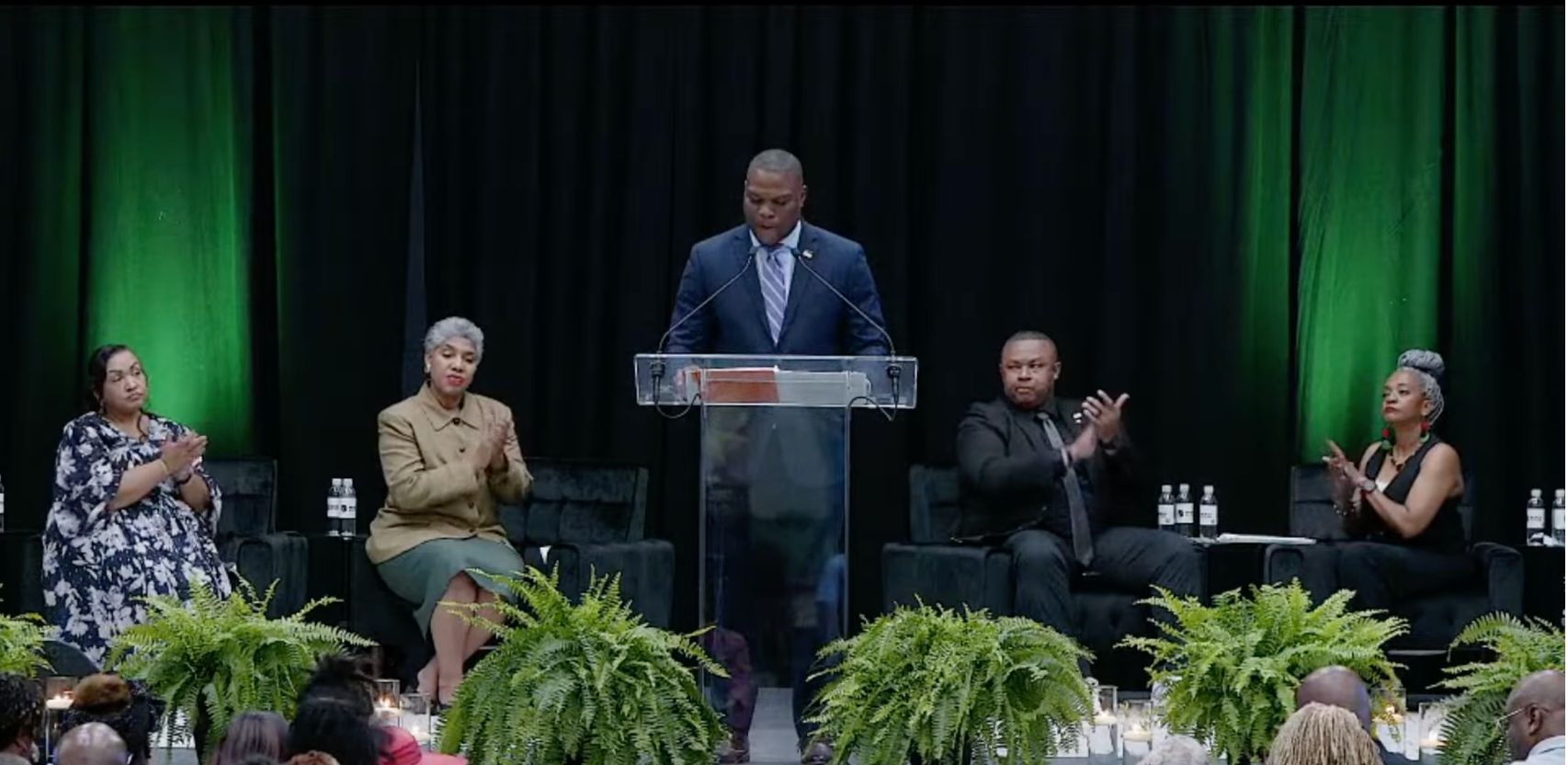

Above photo: City of Tulsa.

Tulsa’s first Black mayor Monroe Nichols announced the creation of a historic reparations plan for Greenwood, the “Road to Repair.”

Tulsa, Oklahoma – Exactly 104 years after Tulsa’s local government deputized white men to loot, bomb, burn, kill and kidnap Black residents of the Historic Greenwood District, the city’s first Black mayor announced the creation of a historic plan for reparations on Sunday.

Inside the Greenwood Cultural Center on the first annual celebration of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Observance Day, newly elected Mayor Monroe Nichols announced the creation of a Greenwood Trust that will be used to collect $105 million to address racial disparities impacting Massacre survivors, descendants and the majority Black residents of north Tulsa.

“This is a critical step to help to unify Tulsans and heal the wounds that for so long prevented generations of our neighbors from being able to recover from the Race Massacre,” Mayor Nichols announced.

Calling the massacre a “stain on the city’s history,” Mayor Nichols asked the audience to imagine the progress in society had Greenwood never been attacked. “We’ve recognized and remembered. Now it’s time to take the next big steps to restore.”

The mayor appeared to criticize a review from the former Biden administration’s Department of Justice in January, which claimed there is no way to provide restitution and justice for the 104-year-old government-sanctioned massacre.

“I have to say, as the calls for repair continue to mount, it is my belief that we can no longer wait to ignore these powerful voices for unity and progress,” Mayor Nichols said, honoring the organizations and individuals who have been pushing for reparations long before he was elected.

The Greenwood Trust

The money collected through the private charitable trust will direct $24 million to a housing fund, $60 million toward a cultural preservation fund and $21 million toward a “legacy” fund that would support the acquisition of land and scholarships for survivors and descendants. They fall in line with recommendations proposed by the city’s Beyond Apology commission and the Justice for Greenwood Foundation.

Since 2001, a state report recommending specific steps for reparations has been largely collecting dust despite efforts by century-old survivors to continue demanding justice and repair.

Last week, the U.S. Senate, in a rare bipartisan move, unanimously passed a bill that would designate Black Wall Street Historic Greenwood District as a national monument. Two living survivors remain: 111-year-old “mother” Viola Ford Fletcher, the oldest living person to publish a memoir, titled “Don’t Let Them Bury My Story“, and 110-year-old “mother” Lessie Benningfield Randle.

Granddaughter Of Survivor Speaks On Racial Trauma

Sunday’s historic announcement closed out Black Wall Street Legacy Fest, a series of events and celebrations commemorating the anniversary of the 1921 Massacre. During a Legacy Fest panel discussion Saturday afternoon, the granddaughter of survivor “mother” Randle opened up about the struggles she experienced when she carried the trauma in silence.

LaDonna Penny serves as the caretaker for her grandmother and Massacre survivor Lessie Benningfield Randle.

“Since we started this journey she’s gotten a lot better. When we started she wasn’t able to sleep,” Penny said. Randle would experience night terrors frequently and needed a night light to sleep. Penny said her grandmother began to heal after people, organizations and entities at the city, state and federal level began to advocate and tell her story.

“I’m happy that my grandmother’s still here to see 110. praying she stays here to see 111,” Penny said.

Tulsa Moves Toward Reparations For 1921 Massacre

Sunday’s reparations announcement comes after years of advocacy from Tulsa organizations like Justice for Greenwood, the Terence Crutcher Foundation and the city’s Beyond Apology commission, which continued a century-long fight of seeking reparations for the theft of property and human lives at the hands of a racist government.

Over 300 Black men, women and children were bullet-ridden, burned or bombed out of across over 37 square blocks during the hours of May 31 and June 1, 1921. Over 3,000 Black Tulsans were temporarily reduced to slavery in concentration camps for three days following the massacre, according to the Tulsa Historical Society. The white mob destroyed over 1,000 homes and over 200 businesses.

Descendants like Chief Egunwale Amusan, Black Tech Street’s Tyrance Billinglsey III, and the Black Wall Street Times editor-in-chief Nehemiah Frank, along with advocates like former mayoral candidate Greg Robinson, the late Rep. Maxine Horner and the late J. Kavin Ross, were all honored for continuing the intergenerational effort for restitution.

They were centered as moving in the same spirit of B.C. Franklin, an attorney and survivor who sued the city of Tulsa from a Red Cross tent days after the Massacre, successfully preventing the city’s efforts to take over the burned and bloodied land.

The community eventually rebuilt an even larger Black Wall Street well into the 1940s before government urban renewal programs caused a decline.

City Steps In After Courts Step Out

In over a century, the American courts have never been kind to survivors of Tulsa’s Black holocaust. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to accept a case brought by the late Charles Ogletree in the early 2000s.

In 2023, Tulsa County District Judge Caroline Wall dismissed the case for survivors “mother” Viola Ford Fletcher and “mother” Lessie Benningfield Randle. The Oklahoma Supreme Court later upheld the dismissal in 2024.

The historic step toward reparative justice for the worst single instance of racial domestic terror builds on previous moves made by the new mayoral administration. Mayor Nichols previously dedicated June 1 Tulsa Race Massacre Observance Day for the first time in the city’s history. He is also making public over 45,000 documents related to the massacre. The actions mirror proposals from Project Greenwood, the Justice for Greenwood’s 13-point plan for reparations.

The reparations plan from Justice for Greenwood also calls for a hospital to be built in north Tulsa, descendant preferences for city contracts, immunity for survivors and descendants from all local taxes and opening a criminal investigation into known massacre victims. It’s unclear if Mayor Nichols plans to act on these proposals.

In addition to the Greenwood Trust, Mayor Nichols’ administration has also dedicated $1 million of the city’s budget to continue the city’s mass graves investigation and the continuation of the Community Engagement Genealogy Project, an effort to identify more descendants of the government-sanctioned 104-year-old racial domestic terror attack.

What’s Next

During a time when far-right conservatives and the Trump administration are weaponizing the weight of the federal government to reshape society in their own ideological image, the decision to pursue reparations has undoubtedly cast Tulsa into the national spotlight.

Oklahoma state Senator Regina Goodwin, Rep. Ronald Stewart and Tulsa City Councilor Vanessa Hall-Harper, two Black lawmakers representing Greenwood and north Tulsa, acknowledged the historic moment while warning of the need to prepare for the pushback.

“It is also very triumphant, a call to all of us, elected officials, businesses, leaders, artists, educators and the youth, to recommit ourselves to justice, equality and opportunity,” Rep. Stewart said.

Mayor Nichols said the investments to restore the Greenwood District “to the community we should have been” will commence within a year of its creation.

“Today, I will be releasing more than 45,000 historical and relevant records directly related to the massacre. These are records that have not been shared publicly to this point,” the mayor said, in response to requests from Justice for Greenwood.

The documents can be found at www.cityoftulsa.org/roadtorepair.

“There are some I am sure, that will say why after 104 years. Others will say, after 104 years, this is not enough. I can tell you, I see it both ways,” Mayor Nichols said. “The Greenwood Trust is the next big step on our road to repair a road that we as Tulsans, as Oklahomans and as Americans will boldly travel together, not compelled by law, but resolved in our commitment to ensure that our tomorrows are far better than our yesterdays.”