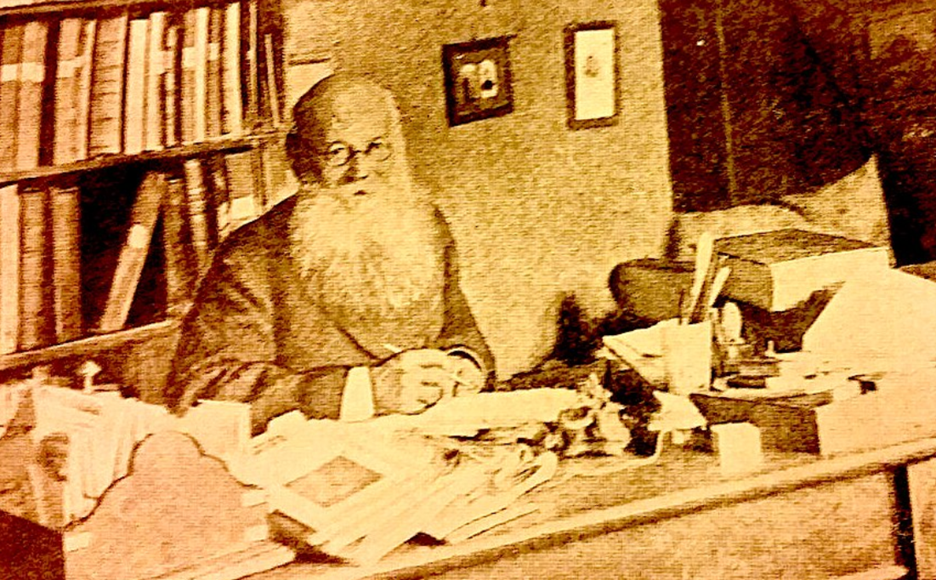

Above photo: Kropotkin at his desk c. 1890. Unknown/Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons.

Cooperation is more important than competition in human survival, argued Peter Kropotkin.

After competition brought two world wars, mutual aid twice sought to rescue humanity. Will there be a third chance?

NOTE: The following is the full text upon which CN Editor Joe Lauria delivered condensed remarks (seen in above video) at the Mut Zur Ethik (The Courage to be Ethical) conference in Sarnach, Switzerland on Aug. 29. Time: 24m 26s.

In our youth there were certain books that stood out and left a lasting impression on us. At the time, these books seemed to change our entire lives, young as our lives were. One would-be genius told me she was 8 years old when she read Montesquieu. I guess I was a late bloomer as I reached about 17 before I started reading serious books.

One of those books came to mind as soon as I read these words in Zeit Fragen (the newspaper of the conference organizers) on what this conference is about:

“The world has changed radically in recent years, and changes radically still. The forces that persist in striving for global supremacy are opposed by others working for peace and a world order based on equality and equal rights. The quest for supremacy comes at a high price: Reason and humanity fall by the wayside, so endangering all of us – those who insist on preserving their power, as well as all others.

This seems to be something those who lead the West, heirs to long traditions of imperial superiority, have not (yet) understood. They have forgotten the treasures of the humanistic tradition, the idea of bonum commune – a good life for all.

We in the West are missing an ethic of common identity, common purpose – an ethic of togetherness. In direct consequence, democracy, the rule of law, and international law are being dismantled. Warmongering supplants the ability to build peace. A cult of irresponsibility prevails.

This makes it all the more important to rethink or return to cultural traditions that have proven their worth in the way people and nations live together.”

The book that immediately came to mind when reading these words was Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution by the Russian prince, Peter Kropotkin.

Who Was Peter Kropotkin?

Born into an aristocratic family in 1842 in Moscow, he became a page to Tsar Nicholas I. As a military officer in Siberia, he took part in geological expeditions for which he won a gold medal from the Russian Geographical Society for discovering that the land from the Ural Mountains to the Pacific Ocean was a plateau and not a plain. A Siberian mountain range was later named for him.

As Siberia correspondent for a St. Petersburg newspaper, he studied peasant social organization. He continued his geographical studies at St. Petersburg university and took part in a polar expedition in 1870. Kropotkin was just as interested in human society as the natural world and was stirred by the 1871 Paris Commune. In 1872 he traveled here to Switzerland where he became involved with the Jura Federation, led by Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin.

Radicalized in Switzerland, Kropotkin returned to Russia with contraband literature and joined an anarchist circle. His first political writings in 1873 argued for a stateless society of workers and peasants owning the factories and the land.

The secret police came after his group for advocating these ideas and Kropotkin was arrested for agitation in 1874 and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress, a scandal for a member of the Russian elite. In jail he was allowed to complete a report he was writing on the Ice Age.

Because of ill health he was moved to a lower security prison from which he escaped and arrived back here in Switzerland in 1876, where began the publication Le Révolté.

Five years later, in 1881, he was expelled from Switzerland at Russia’s request after the assassination of Alexander II, though there was no proof he had a direct role in it. Kropotkin exiled in France and then London after he learned that the Holy League, a tsarist group, intended to kill him for his alleged link to the assassination.

Back in France he was imprisoned for four years before returning to London where he began a publication called Freedom. Inspired by reading Mutual Aid in 1983 I went to its offices in Whitechapel and induced its editors to publish an article I’d written. The paper is still published online.

After the Bolshevik Revolution Kropotkin returned to Russia in 1917 where, despite being opposed to Marxism, he was treated as a friend of the revolution. He refused the offer of a cabinet seat from the Petrograd Provisional Government. His application for residency in Moscow was personally approved by Lenin with whom he met and corresponded. Kropotkin argued with him against the centralization of authority to no avail.

After he died of pneumonia in February 1921 aged 79 his family refused a state funeral offered to him. His Moscow funeral was the last public demonstration of the anarchist movement in Russia as it was fully suppressed by the end of 1921. But in 1935 a station in the Moscow metro was named after Kropotkin.

Kropotkin’s Argument

Kropotkin’s political ideas arose largely from his study of animal life and peasant society during his time in Siberia. It was on the basis of his observation of animal and human cooperation that he concluded that mutual aid, and not mutual struggle, is the primary factor in human evolution and survival. This was an argument in direct contradiction to the evolving consensus at the time put forward by Herbert Spencer and Thomas Huxley of a war for survival of the fittest.

Kropotkin’s argument is essentially this: Human individuals and societies are both competitive and cooperative. The question is which has been more important in the survival of species. Mutual Aid was a response to Huxley’s 1888 book Struggle for Existence and its Bearing upon Man, which promoted the idea of Social Darwinism – that it is, a competitive struggle against others for survival.

This was a misinterpretation of Darwin, Kropotkin argued. In his book’s vast and incisive overview of human history, he shows that it has been predominately the cooperative side of our natures, not the competitive, that has led to our survival until today.

Mutual Aid should be considered, he wrote, “not only as an argument in favor of a pre-human origin of moral instincts, but also as a law of Nature and a factor of evolution.”

It’s Not Love

He rejected the idea that it was love or parental feeling that led to mutual aid.

“It is not love to my neighbour—whom I often do not know at all—which induces me to seize a pail of water and to rush towards his house when I see it on fire; it is a far wider, even though more vague, feeling or instinct of human solidarity and sociability which moves me. So it is also with animals. It is not love, and not even sympathy (understood in its proper sense), which induces a herd of ruminants or of horses to form a ring in order to resist an attack of wolves; not love which induces wolves to form a pack for hunting; … and it is neither love nor personal sympathy which induces many thousand of fallow-deer scattered over a territory as large as France to form into a score of separate herds, all marching towards a given spot, in order to cross there a river.

It is a feeling infinitely wider than love or personal sympathy—an instinct that has been slowly developed among animals and men in the course of an extremely long evolution, and which has taught animals and men alike the force they can borrow from the practice of mutual aid and support, and the joys they can find in social life.

But it is not love and not even sympathy upon which Society is based in mankind. It is the conscience—be it only at the stage of an instinct—of human solidarity. It is the unconscious recognition of the force that is borrowed by each man from the practice of mutual aid; of the close dependency of every one’s happiness upon the happiness of all; and of the sense of justice, or equity, which brings the individual to consider the rights of every other individual as equal to his own.”

Response to Huxley

Mutual Aid published in 1902 is a collection of articles written between 1890 and 1896 for the publication Nineteenth Century as a direct response to Huxley’s 1888 Struggle for Existence and its Bearing upon Man, which Kropotkin writes “to my appreciation was a very incorrect representation of the facts of Nature.”

Social Darwinism emerged during the Gilded Age -– the unrivaled heyday of unregulated capitalism until the resurgent Gilded Age of our own neoliberal era.

In the introduction to Mutual Aid, Kropotkin quotes Huxley about “gladiator’s show” of prehistoric people: “… the weakest and stupidest went to the wall, while the toughest and shrewdest, those who were best fitted to cope with their circumstances, but not the best in another way, survived. Life was a continuous free fight, and beyond the limited and temporary relations of the family, the Hobbesian war of each against all was the normal state of existence.”

Kropotkin said,

“There are a number of evolutionists who may not refuse to admit the importance of mutual aid among animals, but who, like Herbert Spencer, will refuse to admit it for Man. For primitive Man—they maintain—war of each against all was the law of life.”

Kropotkin went on:

“We have heard so much lately of the ‘harsh, pitiless struggle for life,’ which was said to be carried on by every animal against all other animals, every ‘savage’ against all other ‘savages,’ and every civilized man against all his co-citizens—and these assertions have so much become an article of faith—that it was necessary, first of all, to oppose to them a wide series of facts showing animal and human life under a quite different aspect.

It was necessary to indicate the overwhelming importance which sociable habits play in Nature and in the progressive evolution of both the animal species and human beings: to prove that they secure to animals a better protection from their enemies, very often facilities for getting food (winter provisions, migrations, etc.), longevity, and therefore a greater facility for the development of intellectual faculties; and that they have given to men, in addition to the same advantages, the possibility of working out those institutions which have enabled mankind to survive in its hard struggle against Nature, and to progress, notwithstanding all the vicissitudes of its history.”

Kropotkin gives us a tour of history, beginning with mutual aid among animals; among pre-historic people; among what he calls barbarians; in the medieval city and finally in his own day.

His history describes elite institutional efforts over succeeding generations to repress people’s natural instinct to cooperate, imposing conditions of life to divide them so they pose little threat to ruling interests. Despite increasingly sophisticated efforts over the centuries, both ideologically and through the use of force, the resilient, cooperative instinct continues to emerge, however.

Ultimately, Kropotkin says essentially that humanity has a stark choice: cooperate or die.

Distorting Darwin

Kropotkin begins his book discussing the distortion of Darwin’s ideas, arguing that Darwin himself acknowledged cooperation in species such as bees and ants and that his followers overemphasized competition in natural selection. He wrote:

“[Darwin] foresaw that the term which he was introducing into science [survival of the fittest] would lose its philosophical and its only true meaning if it were to be used in its narrow sense only—that of a struggle between separate individuals for the sheer means of existence.

He insisted upon the term being taken in its ‘large and metaphorical sense including dependence of one being on another, and including (which is more important) not only the life of the individual, but success in leaving progeny.’

While he himself was chiefly using the term in its narrow sense for his own special purpose, he warned his followers against committing the error (which he seems once to have committed himself) of overrating its narrow meaning.

In The Descent of Man he gave some powerful pages to illustrate its proper, wide sense. He pointed out how, in numberless animal societies, the struggle between separate individuals for the means of existence disappears, how struggle is replaced by co-operation, and how that substitution results in the development of intellectual and moral faculties which secure to the species the best conditions for survival.

He intimated that in such cases the fittest are not the physically strongest, nor the cunningest, but those who learn to combine so as mutually to support each other, strong and weak alike, for the welfare of the community. ‘Those communities,’ he wrote, ‘which included the greatest number of the most sympathetic members would flourish best, and rear the greatest number of offspring.’”

Animals’ Mutual Aid

Drawing on his experience studying nature in Siberia, Kropotkin then gives copious evidence to demonstrate mutual aid among animals.

He describes how ants share food and work, including building bridges with their bodies to overcome obstacles. Bees work collectively to create and maintain hives.

Migratory birds, such as cranes and swallows, cooperate in long-distance flights by taking turns to lead the flock to reduce wind resistance. Birds protect each other’s young in the nest from predators.

The same goes for mammals like deer, buffalo, and wild horses grouping together to ward off predators. Wolves hunt in packs, share their food and together care for the sick and injured.

Social bonds take precedence over individual survival. In the sea, even lobsters and crabs will practice collective defense.

Environment

Kropotkin points out that harsh conditions, such as in the Siberian tundra, are more likely to engender mutual aid than in less challenging circumstances where individual survival through competitive behavior may take precedence. But even in such circumstances cooperative behavior is essential for group survival.

When defense isn’t needed at a grassroots level, but is instead provided by the state, individualism can start to supplant mutual aid. Hence Kropotkin’s absolute opposition to the state.

In his discussion of animals, he shows how mutual aid in primates leads to more sophisticated social structures. Monkeys and apes share food, grooming and defense, protecting the weaker members of the group.

Small mammals and rodents build and share a tunnel system and use calls to communicate alarm. Penguins and seagulls share incubation of newborns and gather together for defense.

He also points out mutual aid between species, such as birds removing parasites from large mammals and different species of fish banding together to defend against common predators.

Overall, Kropotkin establishes that mutual aid is a natural instinct, not a device, which boosts adaptability and resilience in order to reproduce the species with traits favoring sociability.

Individualistic competition may benefit certain individuals, but it weakens the survival of the group. Competition is found mostly in one species against another. Within a species it is less common than cooperation. When competition does occur within a species it is mostly the result of human-made scarcity, in other words inequality, he says.

With examples from the animal kingdom Kropotkin laid the groundwork to demonstrate that mutual aid is actually fundamental among humans too.

Mutual Aid Among Prehistoric People

Focusing on the San people of Southern Africa and Australian Aborigines, Kropotkin demonstrates that hunter-gatherer societies share tools, food and land. Hunting and gathering is a collective endeavor and the spoils are shared for the benefit of group survival.

Cooperative behavior becomes institutionalized in clans and tribes, held together through ceremony and ritual – without hierarchy or central authority. Disputes are resolved within the tribes through collective mediation promoting social cohesion.

The Great Transition: Mutual Aid Among ‘Barbarians’

Agriculture and the domestication of animals led to a social and political revolution that has challenged mutual aid among humans forever. Sedentary life led to the alliance between chiefs, warriors and shamans, becoming a ruling establishment for centuries – divine kings, priests to legitimize the state and generals to enforce its will.

What Kropotkin called barbarians were tribes transitioning from hunter-gathering to agricultural or pastoral economies. Germanic, Mongols, Slavs, etc. were outside of Greek, Roman and ancient hierarchical and centralized authority. These ancient and classical states dominated through military conquests and the imposition of social stratification, including slavery, enforced through ideology and state violence to repress the natural instinct of mutual aid still dominant in barbarian tribes.

Mutual aid inside barbarian tribes was challenged by emerging hierarchies in the transition to sedentary life. Nevertheless Kropotkin shows how mutual still persisted.

Even though the means of production had changed from hunting and gathering to settled agriculture, in the villages of this era, land, tools and harvests were still shared communally.

Defense also remained a largely a shared obligation in tribal society outside the dominance of standing armies. Social bonds were reinforced in assemblies like the Germanic volkmoot or thing.

Laws were developed to enforce mutual obligations such as communal support during famine, and laws were enforced through communal consensus, not centralized authority.

Kropotkin quotes the Roman historian Tacitus’s description of barbarian societies to show that even as societies and economies became more complex the lack of repressive central authority among barbarian tribes allowed mutual aid to flourish through cooperative institutions.

Battle Lines Are Drawn

The battle lines were drawn in this era within barbarian tribes between the emerging alliance of chiefs, warriors and priests defending private land ownership on the one hand versus the vast population still operating under tribal mutual aid.

This competition within the group’ that created the division between ruled and ruler eventually led to Social Darwinism, a distortion of nature pitting everyone against each other. It is still very much with us today.

Battle lines between the tribes and central authorities such as in Rome had already been drawn and were in time breeched, as barbarians overtook the empire. Their control in the West eventually developed into feudalism.

Throughout all of these momentous changes, Kropotkin argues that the natural instinct of cooperation remained resilient despite increasing assaults against it.

Mutual Aid in the Medieval City

Despite social stratification, especially in the countryside, mutual aid survived in medieval cities in the form of guilds (financial aid, training, and protection for members), communes (free cities as semi-autonomous republics governed by assemblies, like Florence and Ghent) charitable institutions (hospitals, almshouses, community granaries), and in defense and infrastructure such as building canals, cathedrals and city walls.

These cities resisted monarchs and feudal lords to preserve mutual aid even when overseas colonies with the rise of mercantilism and the emergence of the capitalist class undermined the autonomy of the free city states.

Mutual Aid vs Capitalism Until Kropotkin’s Time

Capitalism creates artificial competition and fosters individualism, undermining the natural instincts of cooperation, Kropotkin argued. Resistance to capitalism has come in the form of trade unions, cooperatives, fights against enclosure, strikes and the development of socialist, communist and anarchist organizations and parties as well as charities. Peasant rebellions and utopian movements were efforts to maintain social bonds in the face of the ravages of capitalism and centralized authority.

Kropotkin concludes his book by arguing that humans have a natural propensity to cooperate, which has preserved the species and though suppressed by central authorities, continues to survive despite all efforts to destroy it.

As an anarchist, Kropotkin believed that only decentralized communities could practice mutual aid and not the state.

Mutual Aid and World War

Battle lines between elites and the public – and between elites themselves – twice in the 20th Century led to supreme conflict. The First World War was a war within capitalism itself, each against the other, for dominance of the system, a senseless battle of survival of the fittest in the capitalist bloc and their overseas colonies. The remnants of the feudal system that tried to suppress the mutual aid of the medieval cities collapsed with the fall of the Hohenzollern (Germany), Habsburg (Austria-Hungary), and Romanov (Russia) eagles.

After the war Germany and Turkey were severely weakened, Britain maintained its empire for the time being and a new player made its entrance into the entanglements of Europe, the United States, which had just 20 years earlier emerged as an empire beyond its shores by finishing off the decrepit empire of Spain.

The accumulated greed for wealth and power that culminated in the Gilded Age of capitalism led to the war that was supposed to end all wars. It was the most destructive conflict to that point in history. Competition had not proven to be the engine of progress the Social Darwinists professed it to be but an engine of utter destruction.

Kropotkin surprised and disappointed many of his followers by supporting the Allied side rather than opposing the war altogether, arguing that German aggression needed to be defeated.

The unbelievable carnage in the fields of Europe led to a collective reassessment. The Social Darwinist ethic, which attempted to use science to legitimize socially predatory behavior, had clearly contributed to the unimaginable horrors.

First Post-War Resurgence of Mutual Aid

There was a widespread implicit acknowledgment post war that a return to mutual aid was needed to put humanity back on a course to survival.

Out of this came a series of developments. The League of Nations was established, ill-fated as it turned out to be. In Italy in 1920, in perhaps the most striking example of mutual aid in defiance of capitalist rule, 600,000 Italian workers took part in factory takeovers. These weren’t sit down strikes.

The workers ran the factories as well as freight trains that moved raw material and finished goods in a demonstration of anarcho-syndicalism which showed the bosses weren’t needed to run an industry. The people, through mutual aid, alone could do it by themselves.

Italian capitalist leaders freaked out. They reacted by supporting a movement to repress this massively successful display of mutual aid which threatened capitalism itself. It was called fascism.

Then in 1928, in another display of institutional mutual aid in direct reaction to the breakdown of World War I, 62 nations signed onto the Kellogg-Briand Pact, named after the U.S. and French foreign ministers who negotiated it. The pact sought to outlaw war as an instrument of foreign policy and to promote peaceful resolution of conflicts.

In the U.S. a best-selling 1934 book, Merchants of Death, claimed U.S. banks and corporations plotted to draw the U.S. into WWI. A Senate subcommittee chaired by Senator Gerald P. Nye of North Dakota investigated the book’s charges and found U.S. companies had made massive profits from the war.

Nye’s hearings led to Congress passing laws in 1935, 1936 and 1937 known as the Neutrality Acts making it illegal to lend money or sell arms and ammunition to any country involved in war.

But none of these measures to restore mutual aid would last.

It took only 22 years for Europe to again be plunged into world war.

The Second Post-War Resurgence of Mutual Aid

Once again Big Power competition squashed cooperation among and within nations leading to a second round of worldwide destruction.

When the worst war in human history was over, once again attempts at cooperation emerged. The world sought to take stock of itself, considering it had threatened its own survival through the disruption of mutual aid.

The United Nations was formed to “end the scourge of war,” U.N. agencies were to foster health, development and worldwide cooperation. The U.N. was institutionalized Mutual Aid so to speak.

Adding to the 1945 U.N. Charter’s attempted blueprint to end war, the U.N. enshrined the principles of mutual aid in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted in 1948. These sought to ensure basic rights that preserve mutual aid among peoples. Its preamble reads:

“Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people,

Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law…”

There were other examples of peoples and nations coming to together in cooperation and in opposition to the predatory and individualistic behavior that led to global devastation. The post-war, non-aligned movement, the precursor of today’s BRICS, saw newly decolonized developing countries practice a kind of mutual aid against the dominance of the U.S.-led West.

The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe was an attempt to create a mechanism to defuse Cold War tensions and foster detente and cooperation on key international issues such as disarmament and the uses of outer space.

State-Run Mutual Aid

Workers in Britain threw out wartime leader Winston Churchill and the first government-run health service since Bismarck, the NHS, was established the same year, 1948. Across Western Europe government was put into the service of the public as never before.

Kropotkin of course would not have agreed with government-directed mutual aid in the form of social democracy. Here is where I differ a little with the great Russian anarchist. He saw no positive role for government. Mutual aid had to be practiced locally, from the ground up, without the involvement of the state, he held.

Ideally, this is what the world should strive for. But the world is much more complex than in Kropotkin’s time, and social democracy, as practiced in Western Europe after the war, with a mixed economy and a strong social safety net, may be the best system human beings will ever be capable of.

The US: The Greatest Threat to Mutual Aid

In opposition to these moves to revive mutual aid, the forces of individualism and greed fought back to maintain control. The beginning of the Cold War by the Truman administration, and the subsequent nuclear arms race, was in direct contradiction to efforts to preserve the species through the revival of mutual aid.

The Cold War was driven by the U.S. emerging from WWII with troops and intelligence scattered around the world ready to enforce U.S. access to new markets and resources through invasions and coups installing foreign governments subservient to U.S. interests.

To support this global empire, the U.S. developed a permanent military state that still dominates at home and with declining authority abroad. This militarized economy takes away from the administration of mutual aid among the people and glorifies a single leader and the interests of an elite class over the population.

This came about despite three U.S. presidents who at least tried to warn about the consequences to society of U.S. power.

James Madison warned in 1795:

“Of all the enemies to public liberty, war is, perhaps, the most to be dreaded, because it comprises and develops the germ of every other … In no part of the constitution is more wisdom to be found than in the clause which confides the question of war or peace to the legislature, and not to the executive department. Beside the objection to such a mixture of heterogeneous powers: the trust and the temptation would be too great for any one man … War is in fact the true nurse of executive aggrandizement.”

After every previous war U.S. soldiers returned to the fields and factories and the economy returned to civilian pursuits. But after the Second World War fear of a return to the Depression led to the permanent military economy. Eisenhower’s 1961 warning that this would threaten American democracy – and world peace – has come true.

After Cold War competition nearly led to nuclear annihilation in the Cuban Missile Crisis, John F. Kennedy’s warned in his famed June 1963 American University speech not to humiliate a nuclear weapons state – the Soviet Union. The warning. as seen in today’s Ukraine crisis, has been ignored.

[See: A History of Humiliation]

Kennedy sought to humanize the Soviet people for an American audience in an effort to restore global cooperation and the survival of the species. Some analysts think it led to his own death five months later as clashed directly with the interests of American militarism. JFK favored mutual aid over Big Power competition and potential mutual destruction.

Throughout the Cold War 1950s and into the 1960s, dissent was crushed. If one sought detente, as Kennedy did in his speech, one was usually denounced as a traitor.

Then Henry Kissinger achieved detente in the 1970s. Today one is back to being a traitor if one seeks cooperation rather than confrontation with Russia.

After McCarthy’s 1950s witch hunt was disgraced, sociability led to mass protests against the U.S. war in Vietnam that were not easily crushed. The 1960s anti-consumerist counterculture, and the spread of social revolution in the developing world, posed a threat to the Social Darwinists.

The Attack of the NeoLiberals

The Chicago School of neoliberal economics, in which the state plays almost no role min the economy, leaving individual greed to dominate, facilitated fascistic, U.S.-led dictatorships in Latin America and brought two supreme Social Darwinists to power in the West.

The regimes of Margaret Thatcher in Britain and Ronald Reagan in the U.S. began working diligently from 1980 to dismantle whatever government-run mutual aid exists. It was nearly 50 years ago that the neoliberal movement was begun in earnest and we are still living with.

Thatcher and Reagan set out a worldwide agenda of privatization, free trade, deregulation, and destruction of trade unions and the social safety net. This meant selling off state-owned heavy industries, railways and the gradual privatization of government-run health services. It seems all that will remain of commonly-held property will be parks and public libraries.

Thatcher went much further than saying mutual aid doesn’t exist or shouldn’t exist. She said society itself does not exist. Only the individual does.

There was no clearer declaration that Social Darwinism was alive and well in the late 20th century.

Global Competition vs Global Cooperation

Multilateral institutions such as the U.N., created after the war to foster mutual aid and cooperation between nations, became paralyzed at the Security Council by the Cold War rivalry. (The non-binding General Assembly became the focus of international solidarity during the decolonization period.)

In the fourth decade of the Cold War, Reagan and Thatcher drummed up Big Power competition, heightening tensions, leading to a second near nuclear war in Project Able Danger in 1986.

But in the midst of the Thatcher-Reagan social repression came one of the great outpourings of mutual action geared towards survival of the species. It was a prime example of the resilience of mutual aid that Kropotkin wrote about.

Mass demonstrations against nuclear weapons, especially one million protestors in New York’s Central Park in June 1982, and millions across Western Europe in October 1983, including one million in The Hague and 400,000 in London’s Hyde Park, eventually led Reagan and Soviet leader Mihail Gorbachev to agree at the 1986 Reykjavik Summit to what became the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty.

The demonstrations had been particularly against the deployment of intermediate-range U.S. cruise missiles in Europe. These were removed along with Soviet SS-20s in the agreement.

Will We Survive This Time?

After both world wars the world remembered what had allowed the human race to survive: cooperation and mutual aid. Post-war attempts were made to minimize competition between nations and peoples and to increase mutual aid. The first attempt failed when world war came for a second time. After the Second World War multilateral institutions were put in place in the hope that this time international cooperation could stave off the descent of man to utter destruction.

The end of the Cold War in 1991 brought a brief hope of international cooperation. In the United States there was talk of a “peace dividend,” meaning spending on weapons would now be spent on society. There would be no triumphalism over the defeated Soviet Union, then President George H.W. Bush said. There was talk of a united Europe at peace from Lisbon to Vladivostok.

Instead, Wall Street and U.S. corporate carpetbaggers swept into the former Soviet Union in the 1990s, eyed its enormous natural resources, asset-stripped the formerly state-owned industries, enriched themselves, gave rise to oligarchs and impoverished the Russian, Ukrainian and other former Soviet peoples.

The humiliation intensified with the decision in the nineties to expand NATO eastward despite a promise made to last Soviet premier Gorbachev in exchange for reunifying Germany. Even Washington’s man in the Kremlin, Boris Yeltsin, at first objected to NATO expansion, while then Sen. Joe Biden supported it though he knew it would provoke Russian hostility.

Yeltsin’s successor, Vladimir Putin then closed the door on Western interlopers in order to restore Russian sovereignty and dignity, ultimately angering Washington and Wall Street. Russia sought in treaty proposals with the U.S. and NATO in 2009 and again in 2021 to create a new security architecture in Europe.

Instead Russia’s enormous natural resources and its obstacle to U.S. global dominance has led the West to provoke Russia in Ukraine with the overthrow of the democratically-elected government in 2014. The U.S.-installed government attacked ethnic Russians in the breakaway Donbass region, which defended its democratic rights against the coup.

After failing at repeated attempts of diplomacy, Russia intervened in the civil war in 2022. Fighting continues against NATO-trained and equipped Ukraine amid realistic fears of a nuclear confrontation between NATO and Russia. Despite clear warnings from Moscow of a potential nuclear retaliation, American and German soldiers have attacked Russia by firing U.S. and German missiles into Russia from Ukraine territory risking the ultimate disaster.

Nearly 50 years of neoliberalism and a new Cold War have weakened the institutions of mutual aid. The U.S. seeks to replace international law and the principles of mutual aid in the U.N. Charter with a so-called rules-based order, in which the U.S. alone makes the rules and sets the order.

After two world wars humanity nobly tried to return to mutual aid to save the species. Both times it failed to preserve the peace.

While the old bonds that knit clans and tribes together may have been broken by the individualism of capitalism, Kropotkin saw that it is impossible to completely crush the natural instinct of people to aid one another.

But the tragedy is that this time with nuclear weapons aimed at one another, there may not be another post-war period to try to return to the sanity of aiding one another to survive.