With all the news coming out about possible mass surveillance and the relationship between an alphabet soup of federal agencies and the companies that hold huge swaths of your electronic life, it’s easy to feel powerless. But you’re not. Technology taketh away your privacy, but technology can giveth quite a bit of it back too.

Much of the news of the past week has been about government access to phone and internet “metadata,” which is a part of communications that we almost never think about in the course of normal life.

Here’s what you need to know to make your communications more private:

What is “Metadata” and Why Do You Care?

All communication is broken up into two parts – metadata and message. Metadata is what’s needed for your message to arrive at its intended destination. An address on an envelope is metadata, as is an email address, a phone number and a twitter handle. When you shout someone’s name across a room to get their attention, that’s metadata too.

The message is the letter inside the envelope. It’s everything below the “to/from/subject” information in an email. Everything you say after you connect with someone, either by calling them or shouting at them, is the message.

If the distinction between metadata and message seems a bit arbitrary, that’s because it is. In technology, what’s metadata and what’s message are designated by the programmer’s design, rather than some great dividing line. This is a problem in American law, because message is usually protected by strong laws, but metadata isn’t. Programmers, who are almost never also lawyers, put sensitive material in metadata all the time. And legislators, even fewer of whom are programmers, have never fixed the metadata loopholes in the law.

Given a couple decades of communication technology, you get a situation like the one revealed by the Verizon court order. The mobile phone companies track all cellphone locations and call data, and can uniquely identify every phone, SIM and user. This isn’t because the mobile phone companies are cackling evilly as they put trackers on nearly everyone in America, it’s because in order for cell phones to work, towers need to know where phones are. That’s not surveillance, it’s just how radio waves work. What’s more, in order to build out capacity and maintain service, the telcos need to keep track of how people move around. It’s all part of making their networks work. To the phone company, metadata about who you are and where you go is useful for running their network. Despite some of their ads, they aren’t particularly interested in your personal life. On the other hand, to you, where you go and who you talk to is sensitive information. Right now, you can’t do anything about keeping all of that a secret from your mobile phone company, except not having your phone with you.

The messages that come to and from your phone are another matter. There’s a lot you can do about keeping those private and secure, and doing so helps you live in a safer world – not just from government surveillance, but from anyone who wants to snoop on you for any reason.

On computers and smartphones (which are just smaller computers with hard-to-use keyboards) your main tool for protecting your information, both message and metadata, is cryptography. Cryptography (often also called “crypto”) is a way of using math to rewrite information in a secret code. Since metadata is needed to get information across the network, some level of it is always exposed. For you, the question is where does your metadata end, and the message begin?

Making Crypto Work for You

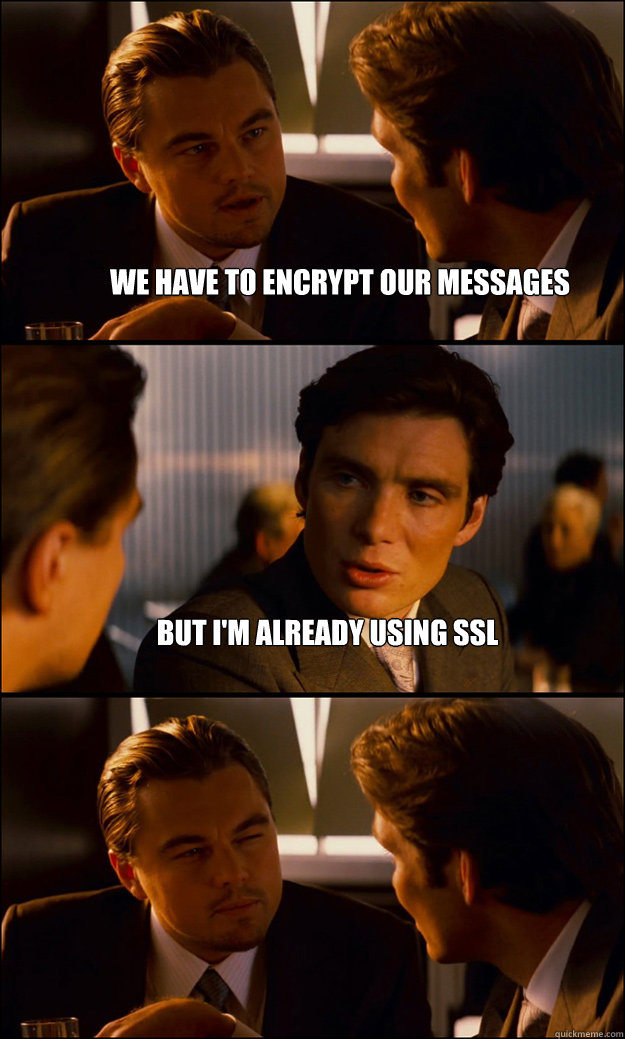

A warning: Computer scientists are terrible at naming things, and trying to get them to explain how things they make work is a world of Lovecraftian horrors. Nowhere is this worse than in crypto, which is full of unintuitive names and nonsensical metaphors. Fortunately you don’t really need to know how cryptography works to use it, though if you want to, there’s a video series that explains the concepts in some detail for a general audience.

Communication crypto works by exchanging “keys,” or long strings of numbers that each side of a conversation uses to encrypt and decrypt each other’s messages. The various schemes for coming up with these shared numbers include symmetric-key exchange,Diffie–Hellman key exchange, and public-key cryptography – but you definitely don’t need to understand the details in order to use keys. All you need to know is that they all involve performing math functions that are easy for a computer to do, but extremely hard to undo. These methods are strong. There’s evidence that even the NSA can have trouble circumventing well-done key exchange crypto, and cracking it en masse is probably still not practical. There are two basic ways to use crypto:

Talking to Bob

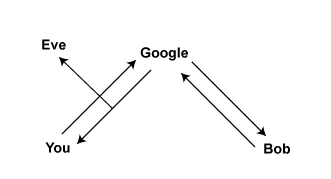

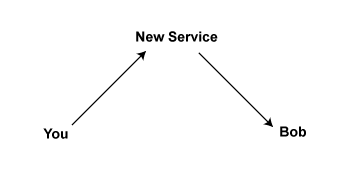

Let’s say you’re trying to talk to your friend Bob. Over the internet, you’re generally going to pass your messages through a server. Let’s say you’re talking to Bob over a Google service (though most other services work similarly).

Obviously, Google can see all of this. But if someone steps into the stream they can see everything, too. This was the case with the cable splices detailed in the 2006 stories of warrantless wiretapping, and in last week’s story about the Verizon order.

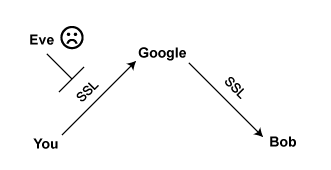

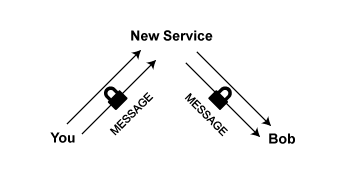

In an attempt to be witty, cryptographers always call the party stepping into the stream Eve. Because Google is good at security, they use something called SSL to hide your traffic from Eve as it passes through the wires (or over the air). You can tell you’re using SSL, also called TLS for no good reason, when you visit a web address that starts with https instead of http. (Gee, thanks for making that so clear, computer scientists.) SSL is effective in blocking Eve, which is why the Electronic Frontier Foundation developed a browser plug-in called HTTPS Everywhere, which helps you put the majority of your web browsing inside SSL and out of view. You should use that. (Disclosure: I’m legally married to an EFF employee, and occasionally seek advice from their legal department.)

HTTPS Everywhere Logo

HTTPS Everywhere Logo

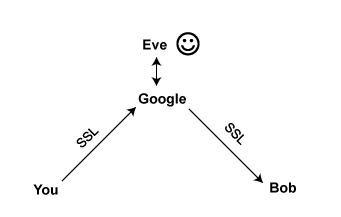

But if Eve has a special relationship with Google, you have another problem. With SSL, Google still has a copy of all your information, metadata and message. You can’t avoid Google having your metadata – the like cell phone towers, they need it to make the network work.

Encrypting Message Data

What now? There’s a fix: You can encrypt your message with a deeper layer of public-key cryptography called “end-to-end encryption.” Even the server that passes the message can’t look at it. Google can still give Eve your metadata, but even Google can’t see your messages, only encrypted gobbledegook. There’s a catch: This kind of encryption isn’t always easy to use. More on that in Part 2.

Even with end-to-end encryption, you have the same problem with metadata being visible to Google that you had before you encrypted anything. You’ve just made Eve go through one extra step – talking to Google – to get it. That might be all the protection you need, depending on your service provider legally resisting blanket requests from the government. If you don’t trust them to do that, then you should use a different service.

But here is where most people, even cryptographers, make their big mistake. We encrypt our messages and feel safe. But without using SSL, even when using a provider that won’t give information to Eve, the metadata is being transmitted unencrypted. You’re not even making Eve take the extra step of asking your provider. Eve can just step into the stream and capture a copy of your metadata as it passes by.

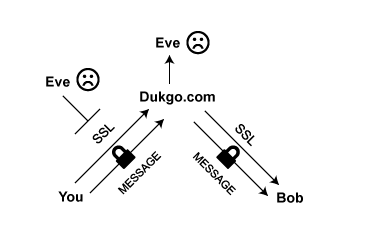

So let’s say you’ve moved to a new chat service. You trust it. It’s run entirely by Swedish hacker teenagers on offshore servers who respond to legal queries with pictures of sarcastic lolcats, not to cooperate with Eve. This new service requires you to encrypt your messages.

But being teenagers, they’ve overlooked a few details, and are accidentally leaking your metadata back to Eve, which is just fine with Eve, since your message data was legally protected anyhow, and when Eve is the NSA, she’s not supposed to keep it.

Oops. You were probably better off staying with your last service.

You abandon the Swedish teenagers then and turn to their somewhat more learned cousins, who have set up independent services around the world with an eye towards security being able to resist intrusion from outside actors. With services like Dukgo.com, and Riseup.net, you can have the best of both worlds: SSL and encrypted messages inside it.

Now you’ve got some privacy back.

Caveat: Who’s Out to Get You?

This advice assumes you’re trying to avoid mass surveillance, of the type that’s been in the news over the last few days, raising constitutional and societal questions. In security we call this an “untargeted attack.” If someone is investigating, surveilling or watchingyou personally, the rules and the advice change. You can no longer count on hiding in plain sight using SSL and encrypted messages. If you believe you need to resist targeted surveillance, things are more complex. Check out security in-A-box to start learning more.