(Some names in this story have been changed to protect those criminalized for migration.)

There isn’t much to see around the River Correctional Center, a small, privately run jail near the Mississippi River and the tiny town of Ferriday, Louisiana. Farmlands and fields stretch in either direction beyond the jail’s barbed wire fence. In the 19th century, enslaved people worked cotton and sugar cane fields here, enriching white plantation owners with their daily labors. The local economy is still extracting profit from maintaining the captivity of people of color today.

River Correctional Center is one of several local jails and state prisons in Louisiana, Mississippi and beyond that have lucrative contracts with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to incarcerate hundreds of people detained in the federal immigration detention system, which has swelled under Trump administration policies that prioritize the “indefinite detention” of thousands seeking refuge in the United States. The 600-bed, medium-security facility is run by LaSalle Corrections, a for-profit prison firm based in Louisiana and Texas that originally built the jail for the local sheriff. In small towns across central and northern Louisiana, sheriffs and one mayor have recently signed fresh contracts with ICE to secure a new source of income.

Sitting in a cafeteria at River Correctional that doubles as a visitation room, Oscar, a middle-age asylum seeker from El Salvador, lifts up his shirt to reveal a massive scar covering one side of his body. He says he ran a successful recycling business back home but was unable to make extortion payments to gang members, who kidnapped him and set him on fire in retaliation. After gangs threatened to kidnap another member of his family, Oscar fled with his mother and cousin to Tijuana and then California, where they were apprehended by border patrol officers in late December. He has since been separated from his family and shuffled across the country as he waits to see an immigration judge about a pending asylum claim.

“No one flees because they want to,” Oscar says, his words translated from Spanish to English by a visiting volunteer.

Oscar is less than optimistic about gaining asylum, despite the evidence of extreme violence scrawled across his body. Immigration judges in Louisiana are notorious for denying the vast majority of claims before them, and few legal resources and Spanish-language services are available inside the jail. Still, he is in contact with advocates and their support networks, which gives him a better chance of accessing legal aid. Plus, there are people on the outside who know that he is being held at a jail in rural Louisiana to begin with. Some others at River Correctional Center are not so lucky.

Immigrants and their advocates talk of Louisiana as a place where people “disappear,” a term increasingly used since mid-2018, when thousands of migrant children separated from their parents under the Trump administration’s “zero-tolerance” policy were lost for months in a tangled web of government agencies. Most immigrant rights groups had never heard of River Correctional Center until March, when dozens of asylum seekers staged a hunger strike at the facility and demanded to be released. News of the strike circulated among activist networks and made national news as hunger strikes spread across the country, drawing attention to the growing number of local jails-turned-immigrant-holding-pens in Louisiana.

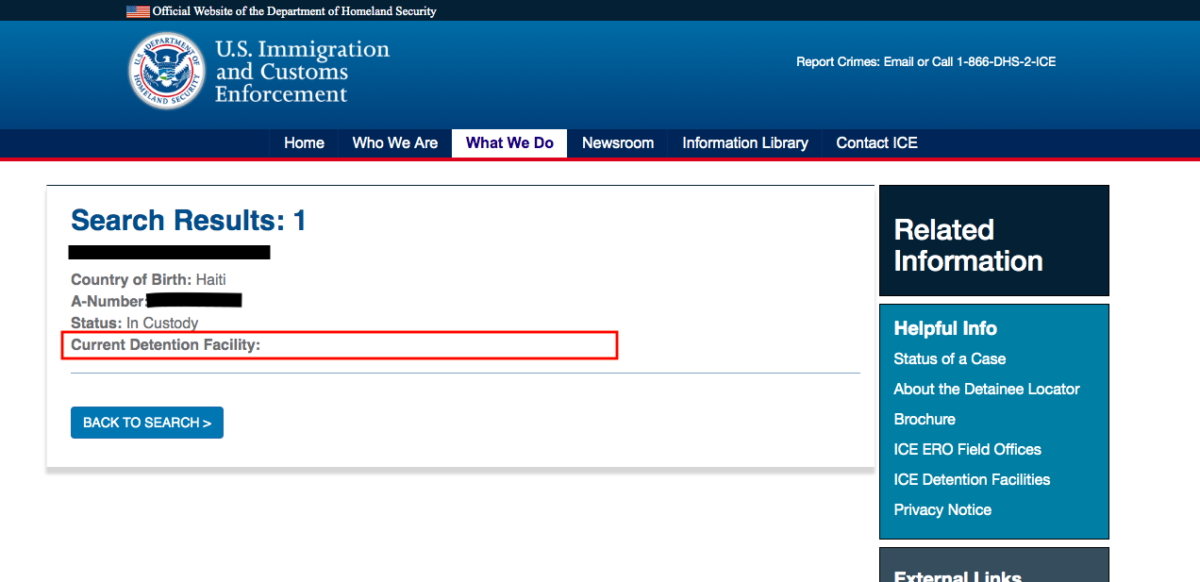

Immigrants from certain parts of Latin American refer to these facilities as “black sites” because they are reminded of secret prisons set up by authoritarian regimes in their home countries, where political dissidents were “disappeared” indefinitely and tortured. Like other “correctional” facilities now holding migrants and asylum seekers in Louisiana, River Correctional is not listed on ICE’s official “detention facility locator” map. ICE prisoners are given a so-called “A-number” to track them within the system, but punch an A-number assigned to asylum seekers held at River Correctional into ICE’s online “detainee locator” database, and the results for “current detention facility” comes back blank:

Maru Mora Villalpando, a longtime Seattle activist who works to end immigration detention and is currently fighting her own deportation, told Truthout that advocates and family members no longer rely on ICE’s “detainee locator” to keep track of people in the system. Instead, advocates dig through online services set up by private prison companies to collect payments for phone calls and commissary in order to locate people who have “disappeared” in the expanding world of immigration detention. Activists and journalists have also used such websites to “discover” local jails in Louisiana and beyond that that have signed fresh contracts with ICE, often by identifying a cluster of surnames in the commissary list associated with countries that migrants are known to flee.

“I think there is a clear attempt to not allow those who want to come [to enter] into the United States, and those that do, to disappear them into the system,” Villalpando said in an interview.

A “Big Business”

Oscar and other immigrants refer to the ICE detention system as un grande negocio, a “big business” that is making as much money off them as possible. They describe being shuffled between various detention centers and prisons across the country, allowing a series of contractors and subcontractors to get their piece of the pie. After he was arrested near the border, Oscar says he spent days in a hielera or “freezer,” the common name for temporary holding pods that human rights groups have condemned for cold temperatures and harsh conditions. He was taken to a detention center in southern California, then flown to Arizona, and then bussed to Tennessee, all in chains and handcuffs. Like others at River Correctional, he was first held at a prison in Tallahatchie county, Mississippi, run by the notorious private prison company CoreCivic before arriving in rural Louisiana.

“We came thinking this country was better than ours, but actually we are treated the same or worse,” Oscar said.

Each additional incarcerated immigrant means more federal funding for their jailers in Louisiana, who have seen their budgets dwindle due to state reforms aimed at reducing the state’s notoriously high incarceration rate. In Louisiana, ICE contractors reportedly earn $62 per day from the federal government to lock up a person incarcerated for immigration charges, more than twice the state rate for holding prisoners convicted on criminal charges. ICE per diems are known to climb as high as $168 per detainee. The number of people held in local Louisiana jails dropped by about 2,700 from 2017 to 2018, but ICE contracts have replaced them with roughly the same number of immigrants from countries across the world, doubling the agency’s detention capacity in the state.

Villalpando expects this trend to continue in Louisiana and beyond as the Trump administration doubles down on deportations and politicians continue pursuing modest reforms that chip away at domestic incarceration rates – and the prison industry’s profit margins.

“Louisiana is an example of what is going to happen with the rest of the nation,” Villalpando said.

“Why Am I Still Here?”

Immigration advocates interviewed by Truthout say they are seeing more people jailed without criminal charges than ever before. While some crossed the border illegally and surrendered to border patrol officers, a misdemeanor offense, others waited for months and applied for asylum at legal ports of entry. However, ICE is still detaining them indefinitely, even after they showed “credible fear” of returning to their home country and opened an asylum case.

One such asylum seeker is “A.J.”, a middle-age man who says he fled gang violence in a Caribbean country and is seeking asylum in the United States. He spent a month waiting at the border in Tijuana where a bottleneck created by the Trump administration’s harsh policies and large numbers of migrants has left thousands stranded on the Mexican side of the border. He was eventually handcuffed by Mexican immigration police and “delivered” to ICE, which accepted his “credible fear” claim but bounced him around the country for months before bringing him to the private prison in Tallahatchie and then River Correctional Center.

“Why am I still here?” A.J. asked in an interview translated by a volunteer.

A.J. is detained indefinitely because ICE considers him a “flight risk” who has been unable to prove “strong ties” to a community in the U.S., according to his asylum documents. Proving “strong ties” could require pay stubs, car titles, utility bills or letters from friends who can prove their citizenship or legal status. A.J. says his mother moved to a major city in the U.S. when he was a child. His mother has since passed away, leaving behind three half-siblings still living in the U.S., whom A.J. has yet to meet in person. He says he is waiting on them to send paperwork to show the immigration judge, in hopes he could be released on parole. If he were released, he would get a job and hire a lawyer, he says, but how can he make enough money for a lawyer while sitting in jail?

A.J. has had trouble staying in touch with his family, particularly in Tallahatchie, where a private company charged high rates for phone calls. It’s unclear if the paperwork will come in time. On top of his stack of asylum papers is a notice to appear in court for a removal hearing within the next week. A.J. speaks little English and cannot read his asylum documents very well, so a visiting volunteer translates the notice by reading it out loud in a language he understands, allowing A.J. to fully grasp the document for the first time.

Of course, not all incarcerated immigrants are free of criminal charges — and focusing on those asylum seekers alone would miss the point. Villalpando says journalists and the public often focus on recent asylum seekers like A.J. because they are not deemed “criminals” and are likely fleeing violence. However, the deportation machine has been churning since the Obama administration and beyond, and incarceration has long been an obstacle for those defending themselves against removal proceedings. Immigration jails are not only filled with migrants fleeing foreign countries, but longtime U.S. residents as well, including those who have lost Temporary Protected Status under President Trump. Human rights groups propose alternatives to jailing people while their immigration cases are pending and demanded that undocumented people be decriminalized, but the government has expanded its system of mass incarceration instead.

“The point is, the system was already there to do these horrible things to everyone, not just asylum seekers,” Villalpando said.

This system has left people like A.J. and Oscar with few options, which explains the wave of hunger strikes that have swept immigration jails across the country and prompted immigration rights groups to spar with ICE over allegations of force-feeding and solitary confinement. An ICE spokesman told Truthout in an email that the agency has tight protocols for hunger strikes and does not “retaliate against anyone” for political protest, but detainees who “violate facility rules are subject to facility discipline” according to the agency’s standards. However, advocates in contact with immigration prisoners say solitary confinement — “the hole” — is a fact of life, particularly for those who resist.

Oscar says some people, under the pressure of captivity, sign their own deportation orders, only to languish in jail for additional weeks or even months as contractors continue to profit off their incarceration. He heard a rumor about one detainee posting bail to the tune of $22,000, with no bondsman available to bring down the cost, but such cases are rare, since most incarcerated immigrants have little to no money. Others keep their heads down in hopes that good behavior could benefit their case — one local sheriff has boasted that immigration prisoners are “super cooperative” — but in Louisiana, judges consistently deny petitions for parole and asylum claims, even for those without disciplinary records.

In March, hunger strikers at River Correctional Center demanded to see different judges and be given a real chance to be released on parole or bail, along with an end to “psychological torture” inflicted by corrections officers. While it’s unclear if any progress has been made toward these demands, Villalpando says the tactic is effective; otherwise ICE would “let people starve” rather than attempt to shut down the strikes. Oscar seems to agree.

“Vamos a luchar,” he says. “Let’s fight.”