Above Photo: Aurich Lawson / Getty

Companies’ obsession with efficiency hasn’t always been good for workers.

Until the 1980s, big companies in America tended to take a paternalistic attitude toward their workforce. Many corporate CEOs took pride in taking care of everyone who worked at their corporate campuses. Business leaders loved to tell stories about someone working their way up from the mailroom to a C-suite office.

But this began to change in the 1980s. Wall Street investors demanded that companies focus more on maximizing returns for shareholders. An emerging corporate orthodoxy held that a company should focus on its “core competence”—the one or two functions that truly sets it apart from other companies—while contracting out other functions to third parties.

Often, companies found they could save money this way. Big companies often pay above the market rate for routine services like cleaning offices, answering phones, staffing a cafeteria, or working on an assembly line. Putting these services out for competitive bid helped the companies get these functions completed at rock-bottom rates, while avoiding the hassle of managing employees. It also saved them from having to pay the same generous benefits they offered to higher-skilled employees.

Of course, the very things that made the new arrangement attractive for big companies made it lousy for the affected workers. Not only were companies trying to spend less money on these services, but now there were companies in the middle taking a cut. Once a job got contracted out, it was much less likely to become a first step up the corporate ladder. It’s hard to work your way up from the mailroom if the mailroom is run by a separate contracting firm.

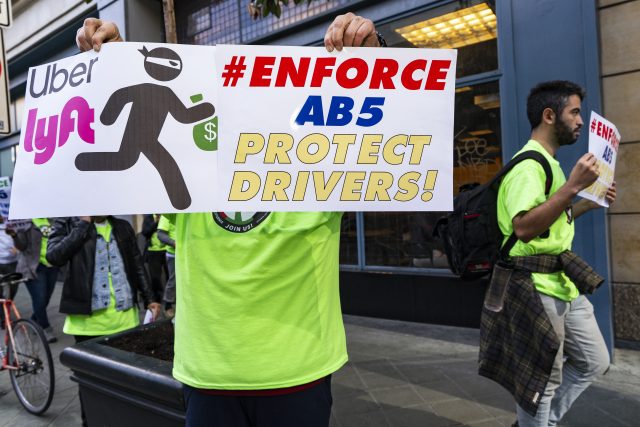

An important question in the coming years will be whether the contracting trend continues to gain steam—or whether opponents of the practice can convince companies to knock it off. Last year, for example, California passed AB 5, legislation that makes it more difficult for companies to classify their workers as independent contractors. Other states are considering following in California’s footsteps. Labor rights advocates hope that a mix of legislation, litigation, and public education campaigns can convince companies to treat more of their workers as employees.

It won’t be easy. Contracting strategies save companies a lot of money, and at this point they’re deeply rooted inside corporate cultures. But no one knows for sure whether the future will see more and more contracting—or if we’ll see a return to the more egalitarian workplaces of the mid-20th century.

“This practice has continued to move up the skill ladder”

A 2017 New York Times story illustrated how the contracting trend has affected ordinary workers. It compared the experience of a janitor at Kodak in the early 1980s (a time when Kodak was considered a successful high-tech firm) to an Apple janitor in 2017. Janitors’ pay, adjusted for inflation, had stayed about the same over 35 years, the Times‘ Neil Irwin calculated. But almost everything else about the job had changed.

As employees, Kodak janitors enjoyed paid vacation time, tuition reimbursements, job security, and opportunities for advancement inside Kodak. Irwin profiled one woman who was able to work her way up from a janitorial job to a professional-track IT job.

By contrast, Irwin reported, Apple janitors were employees of dedicated janitorial contracting firms that bid for work cleaning Apple’s offices. These workers got none of the perks that came with being an Apple employee, no real job security, and no opportunities to move up inside the company.

Similar trends can be found in a wide range of other industries. Today, if you stay at a brand-name hotel, there’s a good chance the person who checks you in and the person who cleans your room don’t work for the company whose name is on the building. If you call about a problem with your home Internet service, you’re likely to talk to someone at a sub-contracted call center. If a broadband technician comes to visit your home, that person is probably a contractor, too.

“Many tech companies solved this problem by having the lowest-paid workers not actually be employees. They’re contracted out. We can treat them differently, because we don’t really hire them. The person who’s cleaning the bathroom is not exactly the same sort of person. Which I find sort of offensive, but it is the way it’s done.”

And it’s not just janitors, housekeepers, and call center workers. “This practice has continued to move up the skill ladder,” author and Brandeis professor David Weil told me in a late February interview. Today, even many white-collar workers find themselves working for high-profile companies as contractors, not full employees.

The contracting trend has transformed corporate America into a two-tier economic system. If you’re lucky enough to get hired as an employee of a Fortune 500 company, you can expect generous benefits, decent job security, and significant autonomy on the job. Those who don’t make the cut wind up working for one of these companies’ many subcontractors. That likely means meager benefits, precarious employment, and few opportunities for advancement.

The existence of such a two-tier workplace is especially ironic in Silicon Valley, a region that takes pride in its egalitarian ethos. Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt gave a remarkably candid assessment of the situation in 2012, in a statement quoted by author Chrystia Freeland.

“Many tech companies solved this problem by having the lowest-paid workers not actually be employees. They’re contracted out,” Schmidt said. “We can treat them differently, because we don’t really hire them. The person who’s cleaning the bathroom is not exactly the same sort of person. Which I find sort of offensive, but it is the way it’s done.”

Subcontracting makes labor law violations more likely

Labor law requires that workers be paid a minimum wage, get overtime pay, have access to compensation for injuries, etc. In principle, the contracting firm can act as a worker’s employer and make sure it complies with all of these rules—freeing the hiring company from having to worry about it.

But in practice, subcontracting arrangements often lead to violations of labor law. A big company probably wouldn’t take the legal risk of paying a worker below minimum wage, for example. But a small janitorial firm might be more willing to take this kind of legal risk. The market for janitorial services is extremely competitive, with low profit margins. Under-paying workers might be the only way to make a profit. And there are so many small janitorial firms that any single firm is unlikely to get audited by the authorities.

This is a common problem in franchised businesses. For example, many major hotel chains today operate as franchises, licensing their name to local investors who actually build and own each hotel. These investors get a lot more than a name. They get an elaborate rulebook specifying every aspect of how the hotel should be operated: how big the rooms should be, what amenities they should offer, how to decorate the lobby, how front desk and housekeeping staff should dress, and so forth. To ensure a consistent customer experience, franchisors closely monitor franchisees for compliance with these rules.

Franchisees sometimes hire a third company to actually manage the hotel. That company, in turn, often turns to small staffing companies to provide workers in particular categories—like housekeepers or front-desk people.

The situation is similar in the restaurant business. Companies like McDonald’s and Subway license out their brands to hundreds of small business owners, each of which is expected to comply with a thick book of rules and regulations. Once again, the brand owner closely monitors whether the franchisee is following the rules.

In principle, this can be a win-win for everyone involved. The brand gets to expand without having to raise millions of dollars in capital—and without having to worry about its local employees mismanaging its multi-million dollar hotel investment. Meanwhile, would-be entrepreneurs and investors can become owners of a successful hotel or restaurant without having to create a new brand from scratch.

But as Brandeis University’s David Weil pointed out in an influential 2014 book, there’s a curious blind spot in a lot of these franchising agreements: compliance with labor law. Brand owners could carefully monitor franchisees and operating companies to ensure that they are paying minimum wages, offering overtime pay, dealing appropriately with sexual harassment complaints, and so forth—just as they closely regulate employee uniforms and room cleaning standards.

But in practice that’s not what happens. To the contrary, franchisors use the franchise agreement as a way to shield themselves from liability. When workers try to sue a brand owner for labor law violations by its franchisee, the larger company invariably disclaims any responsibility, arguing that the dispute is purely between the worker and the local business owner.

In practice, this leads to more violations of labor law. One 2012 study by Weil and a co-author found that, even after controlling for the type of neighborhood and other factors, franchised restaurants were 24 percent more likely to have labor law violations—like failure to pay overtime or asking workers to work off the clock—than restaurants owned directly by a brand owner.

That’s not too surprising: franchisees are often operating under tight profit margins, so under-paying their workers could make a big difference in their bottom line. They also don’t have the high profile or deep pockets of a large restaurant brand owner. That makes them a less attractive target for lawsuits and enforcement efforts by government officials.

Research has found something similar in the hotel industry, Weil writes: hotels managed by independent management companies are far more likely to have violations of the Fair Labor Standards Act than hotels managed directly by either franchisees or brand owners—both of which have more to lose if they’re caught breaking labor laws.

Complex subcontracting can create safety risks

On March 10, 2006, two teams of workers were working on an AT&T cellular tower in Talladega, Alabama. The company, which had recently merged with Cingular, wanted work done quicklybecause of an upcoming NASCAR race. One team of workers was lowering a 50-pound antenna from the top of the tower, while another two-person team was working inside the shelter.

Tragically, the upper team’s rope snapped just as the team on the ground was leaving for lunch. That 50-pound antenna fell 200 feet and struck one of the workers, William Cotton, killing him.

On one level, it was a freak accident. But on another level it was an illustration of the problems that can crop up when safety-critical work is spread out among many subcontractors.

According to ProPublica, AT&T hired a management company called Nsoro to handle the antenna replacement work. Nsoro, in turn, hired a company called WesTower Communications, which in turn hired a third company called ALT Inc. Meanwhile, AT&T hired yet another company, Betacom Inc., to do work in the shelter at the base of the tower.

AT&T itself didn’t take an active role in supervising work at the site. That was left up to contractors to work out among themselves. Yet the rigid requirements of the contract made it difficult for the contractors to complete the work safely.

Josh Cook, the foreman of the team raising the antenna later testified that he told his immediate supervisors that “I was not gonna work above others, and I was gonna have a hard time completing the job because of poor planning on the job.” His bosses, he said, “made some phone calls on my behalf” asking for another week to complete the work. However, “they got denied and told me I needed to be able to test on Tuesday.”

When the Cotton family sued AT&T along with the contracting companies, AT&T argued that it should be dismissed from the lawsuits because it wasn’t responsible for the decisions of other companies. AT&T ultimately settled the case on undisclosed terms.

Worker liability law gives companies a perverse incentive not to try to improve the safety of workplaces managed by subcontractors. In deciding on liability, courts look at whether a company had practical control over safety-related decisions at a worksite. If it did, then it’s more likely to be found responsible for any injuries or deaths. That means a company that proactively tries to ensure worker safety faces higher, not lower, liability if a non-employee is injured or dies on the job.

Things appear to be even worse in the coal mining industry. In recent decades, large coal companies have contracted work out to smaller companies with meager financial resources. Weil writes that, according to mining data between 2000 and 2010, “contract miners in underground operations face significantly higher rates of traumatic injuries than miners working as direct employees of operators in otherwise comparable mines.”

With little capital and thinner margins, these smaller companies couldn’t necessarily afford the sophisticated safety equipment or conservative safety procedures used by larger mining companies. At the same time, many of the firms were judgment-proof: if they were responsible for a major accident, they’d quickly go bankrupt, with few assets for affected families to seize.

“You are a second-class citizen here”

Shortly after David Weil published his book The Fissured Workplace in 2014, President Obama tapped him to lead the federal government’s wage and hour laws—a job that’s made more difficult by the proliferation of subcontracting relationships.

In a recent phone interview, Weil told me about a striking meeting he had on a 2016 visit to Silicon Valley to talk to technology workers, venture capitalists, Uber drivers, and others. He met with a group of contractors at leading technology companies, who described how the expansion of contracting affected their standing at their companies.

Most big tech companies require employees to carry badges while on company property, and the color of the badge frequently reflects the employment status of the worker. Contract workers told Weil that this system was a constant reminder that they lived in a two-tier workplace.

If you were a contract worker, you paid for your meal. If you had an employee badge you didn’t have to pay. If you had the colored kind of badge [indicating contractor status], you had to enter certain kinds of doors. If you had the colored badge, you were allowed to come to the holiday party, but you weren’t allowed to bring anybody. If you had the other badge you could bring in friends and family. The people talked about it as a constant reminder that you are a second class citizen here and don’t forget it.

The growth of the subcontracting economy is partly about shifting interpretations of the law, and it’s partly about technology making it easier to keep track of complex subcontractor relationships. But to an important extent the subcontractor economy is about workplace culture.

Fundamentally, companies contract out more and more work because they, and their elite employees, feel that it’s legitimate to do so. Solidarity between workers and management is seen as passé—replaced by an ethos of ruthlessly transactional bargaining. Many corporate executives simply don’t consider it their problem to ensure the people who clean their offices are being paid fair wages—or that programmers with contractor badges are treated with respect by employees.

California’s AB 5: A first step away from the subcontracted workplace

I recently talked to Shannon Liss-Riordan, a lawyer who has made a career out of suing companies who mis-classify workers as independent contractors.

This is a different trend from the one I’ve been discussing so far, but it’s closely related. Sometimes companies contract work out to other companies who act as a worker’s official employer. But in other cases, companies simply declare a worker to be an independent contractor—and hence ineligible for benefits as an employee. Uber and Lyft have famously done this for hundreds of thousands of drivers, for example.

Liss-Riordan told me that companies do this because it “saves companies so much money, they’re going to push the envelope as much as they can. Not only do they not have to comply with wage laws, don’t have to pay into wage funds, don’t have to pay workers’ compensation, don’t have to pay the employers’ share of payroll taxes. And they transfer the risk and expenses of running a business to their workers.”

Last year California passed AB 5, legislation designed to crack down on misclassification of employees. The law established a clearer, more expansive definition of employment. Supporters of AB 5 hope the law will force companies across California to bring more workers directly onto their payrolls.

As AB 5 forces companies to rethink how they deal with independent contractors, it could also prompt a broader conversation within companies about what kind of workplace they want to have. Relegating a bunch of workers to second-class status via contracting arrangements might save a company some money, but it can also create frictions and resentments within the workplace.