Above Photo: Michael Nigro/Pacific Press/LightRocket/Getty Images. Dakota Access pipeline protesters faced off with law enforcement on the day their camp was slated to be raided, Feb. 22, 2017, in North Dakota.

Google is blocking our site. Please use the social media sharing buttons (upper left) to share this on your social media and help us break through.

THE PRIVATE SECURITY firm TigerSwan, hired by Energy Transfer Partners to protect the controversial Dakota Access pipeline, was paid to gather information for what would become a sprawling conspiracy lawsuit accusing environmentalist groups of inciting the anti-pipeline protests in an effort to increase donations, three former TigerSwan contractors told The Intercept.

For months, a conference room wall at TigerSwan’s Apex, North Carolina, headquarters was covered with a web-like map of funding nodes the firm believed it had uncovered — linking billionaire backers to nonprofit organizations to pipeline opponents protesting at Standing Rock. It was a “showpiece” for board members and ETP executives, according to a former TigerSwan contractor — part of a project that had little to do with the pipeline’s physical security.

In August, the law firm founded by Marc Kasowitz, Donald Trump’s personal attorney for more than a decade, filed a 187-page racketeering complaint against Greenpeace, Earth First, and the divestment group BankTrack in the U.S. District Court of North Dakota, seeking $300 million in damages on behalf of Energy Transfer Partners. The NoDAPL movement, the suit claims, was driven by “a network of putative not-for-profits and rogue eco-terrorist groups who employ patterns of criminal activity and campaigns of misinformation to target legitimate companies and industries with fabricated environmental claims.”

“It was as if the entire campaign came in a box. And of course it did,” the suit alleges. “Its objective was not to protect the environment or Native Americans but to produce as sensational and public a dispute as possible, and to use that publicity and emotion to drive fundraising.”

Among the nonprofit network’s alleged crimes: “perpetrating acts of terrorism under the U.S. Patriot Act, including destruction of an energy facility, destruction of hazardous liquid pipeline facility, arson and bombing of government property risking or causing injury or death.”

“We felt compelled to file the lawsuit against Greenpeace and others because we want the truth to come out about the illegal actions that took place in North Dakota and the funding of these actions,” ETP spokesperson Vicki Granado told The Intercept. “In many cases, the only way the truth comes out is through the legal process.”

The case was filed under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, passed in 1970 to prosecute organized crime — primarily the mob. Greenpeace says it amounts to a strategic lawsuit against public participation, or SLAPP, designed to curtail free speech through expensive, time-consuming litigation.

“It grossly distorts the law and facts at Standing Rock,” said Greenpeace general counsel Tom Wetterer. “We’ll win the lawsuit, but it’s not really what this is about for ETP. What they’re really trying to do is silence future protests and advocacy work against the company and other corporations.”

“[The lawsuit] had some major racist overtones. They were basically saying that we were not intelligent enough to know for ourselves what the possibilities were in case the pipeline were to leak. They were basically saying we were manipulated,” said Linda Black Elk, a member of the Catawba Nation who lives on the Standing Rock reservation and organized against the pipeline months before the protests began. “I think the whole purpose of it is to scare tribes from further activism when it comes to the fossil fuel industries and to scare these green groups to keep them from supporting us in those future fights.”

A Short-Lived Line of Work

TigerSwan, which got its start working U.S. government contracts in Afghanistan and Iraq, was hired by Energy Transfer Partners to coordinate the DAPL operation in September 2016, after dogs handled by private security officers were caught on film biting pipeline opponents. The firm began collecting information on the movement’s funding streams soon afterward, submitting intelligence to ETP via daily situation reports, more than 100 of which were leaked to The Intercept by a TigerSwan contractor.

But the effort to build a lawsuit began in earnest in January. TigerSwan personnel were tasked directly by lawyers working for ETP with fulfilling information requests, according to two former contractors. Situation reports from the beginning of February note that the company planned to “continue to proceed with the ETP legal team’s requests.”

In response to the requests, TigerSwan personnel sent reports on trespassing incidents and pipeline sabotage, including information about who was suspected to be involved and monetary damages caused by the work stoppages. The firm also compiled descriptions of movement leaders and individuals arrested by law enforcement, and tracked donations to DAPL-related GoFundMe accounts. Much of the intelligence collection was carried out via fake social media accounts and infiltration of protest camps by TigerSwan operatives.

According to the former contractors, the company intended to sell its legal investigative services to future clients. A PowerPoint presentation obtained by The Intercept, which a former contractor described as marketing material to attract a new contract, shows TigerSwan applying its follow-the-money tactics to a new pipeline fight against Pennsylvania’s Mariner East 2 project. The presentation traces nonprofit funds to various “action arms,” which include activist groups — Lancaster Against Pipelines and Marcellus Shale Earth First — as well as a member of the press, StateImpact, a regionally focused public radio project.

“As concerns StateImpact, the TigerSwan graphic is incorrect,” editor Scott Blanchard told The Intercept. “StateImpact, which covers Pennsylvania’s energy economy, is independent of outside influence and is not aligned with any stakeholders.”

While TigerSwan eventually landed security work on the Pennsylvania pipeline, its RICO work for Energy Transfer Partners was short-lived. By early March, the legal team working for ETP had pulled the security firm off the lawsuit. Former TigerSwan contractors speculated the firm’s lack of experience building legal cases made it ill-equipped for the project.

Michael Bowe, the Kasowitz attorney representing ETP in the RICO case, told The Intercept, “We did not retain or work with TigerSwan.” Former TigerSwan personnel agreed that the ETP lawyers working most closely with TigerSwan were not with Kasowitz.

ETP declined to comment on TigerSwan’s work, stating, “We do not comment on any specifics related to our security programs.” A TigerSwan spokesperson stated, “We do not discuss the details of our efforts for any client. We are proud of our work to provide the very best in consultative risk management services to our clients around the world.”

Hunting Paid Protesters

Internal documents and interviews with the former TigerSwan contractors display some of the fruits of the firm’s investigation, which include claims that echo prominent right-wing conspiracy theories.

A PowerPoint presentation created in the fall of 2016 describes what TigerSwan dubbed the Billionaire’s Club: “an exclusive group of wealthy individuals, [which] directs the far-left environmental movement.” Several slides are dedicated to the anti-pipeline nonprofit Bold Nebraska, whose parent organization, Bold Alliance, is named in the ETP suit.

“Underlying Bold Nebraska’s homespun, grassroots facade is a significant, growing, well-funded and well-organized financial support network originating from wealthy far-left environmental interests thousands of miles away,” one slide states. The language is pulled verbatim from a 2014 report by the Republican minority staff of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, titled “Chain of Environmental Command: How a Club of Billionaires and Their Foundations Control the Environmental Movement and Obama’s EPA.”

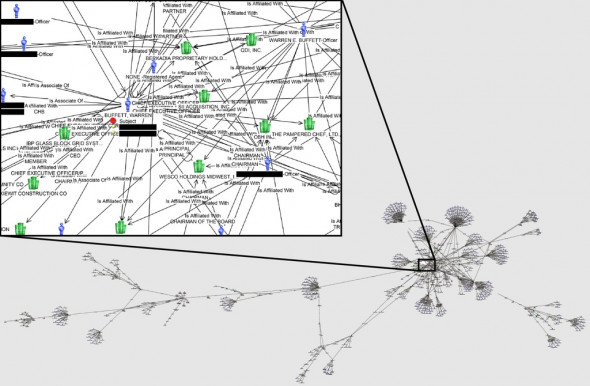

TigerSwan claimed that among the wealthy interests behind Bold Alliance was billionaire philanthropist Warren Buffett, whose donations to foundations that support environmental causes, one slide states, benefited an oil-by-rail business owned by Buffett’s investment company Berkshire Hathaway. Buffett also appears at the center of a TigerSwan links map, obtained by The Intercept, meant to depict movement funders and influencers.

One of the theory’s most obvious flaws is that Buffett has a significant financial stake in the Dakota Access pipeline. Berkshire Hathaway is the largest investor in the oil and gas firm Phillips 66, which owns a 25 percent stake in DAPL. Buffett did not respond to a request for comment.

Jane Kleeb, founder of Bold Alliance, told The Intercept that the group raised money for food and shelter at the DAPL resistance camps. They also had an indigenous staff member on the ground for six months who was involved in organizing protests.

“We’d be happy to take Buffett’s millions, but we don’t have any of that money,” she said, noting the organization relies on thousands of small donors. “There’s literally never been a foundation or a major donor that has given us money and said, ‘You have to do XYZ and target XYZ person.’”

“It’s remarkable that because we are a nonprofit and because I get paid a salary, and I pay our organizers a salary, that somehow makes us a paid protester,” Kleeb added.

Indeed, according to one of the former TigerSwan contractors, a goal of the firm’s RICO work was to identify “paid protesters.”

Throughout the protests, prosecutors and police also took interest in identifying such protesters, indicating that the oil industry’s hunt for a conspiracy was taken up by the public sector.

Multiple TigerSwan situation reports note law enforcement efforts to follow the money. For example, on March 3, a TigerSwan operative wrote, “Spoke with FBI Agent Tom Reinwart in reference to funds being funneled to protesters.” Another report from February 11 describes the Bureau of Indian Affairs tracking individuals “assessed to be assisting in the facilitation of moving money and supplies to the camps.”

Meanwhile, Lynn Woodall of the Morton County Sheriff’s Department also regularly forwarded a protester social media activity bulletin from a Gmail account to an array of law enforcement officials. The bulletins summarized Facebook and Twitter statements made by DAPL opponents, tracked the progress of various anti-DAPL fundraising campaigns, and at times noted posts made by groups named in the lawsuit — including 350.org, Greenpeace, and Earthjustice — under a category labeled “Protest Supporters and Amplifiers.” In at least one case, the bulletin was forwarded to a TigerSwan operative.

A spokesperson for Morton County told The Intercept that a law enforcement staff member collected the fundraising information for “situational awareness.” Neither the FBI nor the Bureau of Indian Affairs responded to The Intercept’s requests for comment.

State’s attorneys were also interested in funding linked to media coverage of the protests, repeatedly singling out Democracy Now, the news outlet whose footage of private security dogs attacking protesters attracted widespread criticism of the pipeline project and galvanized many to join the opposition movement. In a motion filed last December as part of a criminal case against pipeline opponents, state’s attorney Ladd Erickson repeated right-wing talking points. “Some DAPL protester videos are designed for fundraising, to get actors weeping into cameras,” he said, adding, “Pretend journalists like Amy Goodman of Democracy Now or The Young Turks have published manipulated DAPL social media videos with faux narratives in an attempt to be recognized as a news source by those who are duped by fake news.”

In a November 29 email, the acting state’s attorney of McKenzie County, Todd Schwarz, relayed to a North Dakota State and Local Intelligence Center officer a secondhand story he’d heard about someone a colleague sat next to on a flight. “He indicated to Ron that he is a paid protester, $ 3000/day plus expenses. His check comes from Democracy Now who receives their money through the DNC from the Clinton Foundation. I have no way to confirm this but was asked to pass it to you.” Schwarz noted it was “the first time I’ve had it confirmed from the person who actually heard it from the paid protester.” Schwarz did not respond to a request for comment.

“These claims are baseless and absurd,” Julie Crosby, general manager for Democracy Now, told The Intercept. “The Young Turks’ Jordan Chariton took six trips to Standing Rock, where he conducted interviews that shined a light on the truth and raced to cover the front lines of the demonstration,” a spokesperson for the network told The Intercept, calling the narrative pushed by ETP “a continuation of right-wing, corporate intimidation tactics.”

Of course, as police and prosecutors searched for the big-money backers of the protest movement, they were receiving their own share of billionaire support. Throughout the protests, police used ETP equipment including ATVs, snowmobiles, and a helicopter. This past October, ETP paid the state of North Dakota $15 million for law enforcement expenses, and went on a tour of pipeline counties in Iowa, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Illinois, handing out giant checks totaling $1 million — “gifts without condition,” as one ETP executive put it.

An activist stands in silent protest by a police barricade near Oceti Sakowin Camp on the edge of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation on Dec. 4, 2016, outside Cannon Ball, N.D. Photo: Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images

Using Lawsuits to Chill Free Speech

“When it was adopted, RICO was thought to be a mafia tool,” Jeffrey Grell, who teaches courses on RICO at the University of Minnesota School of Law, told The Intercept. “Now it’s going through a renaissance,” he added, noting that while federal courts tried to limit applications of the law, winning the case is often not the primary motive of those filing charges.

“I do not think this pipeline claim is a very legitimate use of this statute … but in legal reality, whether you have a good claim or not does not matter,” Grell said. “If you are an energy company, you have a lot more money than some of these protest groups, so paying a lawyer for two or three years to sue these protesters, who cares? But I guarantee you, the protest groups, they’re going to care.”

“If you have got money in our country, you can use litigation for a lot of purposes, and many times those purposes are not to win a court case.”

Marc Kasowitz’s firm was also behind a RICO suit filed last year against Greenpeace on behalf of logging company Resolute Forest Products. That suit was dismissed in October, although Resolute has filed an amended complaint.

Kasowitz attorney Michael Bowe told Bloomberg Businessweek that Energy Transfer Partners and Resolute are not the only companies with an interest in suing Greenpeace. “When Greenpeace directly attacks a company’s customers, financing, and business, that company has little choice but to legally defend itself,” he said. “I know others who are considering having to do so and would be shocked if there are not many more.”

Several states have passed “anti-SLAPP” legislation in an effort to counter the use of lawsuits for the purpose of chilling free speech, but North Dakota is not one of them. “There’s no question that whether it’s a civil damages lawsuit or a criminal prosecution, if part of what’s motivating it is a desire to suppress speech, that it’s a First Amendment problem,” Seth Berlin, an attorney who has defended the First Amendment rights of advocacy groups and political organizations, told The Intercept.

“It’s a big threat to the environmental movement,” said Wetterer, the Greenpeace lawyer. “These baseless lawsuits have to be thrown out at the initial stage because the longer they go on, the corporations win.”