Above Photo: Steve Schlotterbeck presented at a petrochemical industry conference in Pittsburgh on Friday. Credit: Sharon Kelly, DeSmog

Steve Schlotterbeck, who led drilling company EQT as it expanded to become the nation’s largest producer of natural gas in 2017, arrived at a petrochemical industry conference in Pittsburgh Friday morning with a blunt message about shale gas drilling and fracking.

“The shale gas revolution has frankly been an unmitigated disaster for any buy-and-hold investor in the shale gas industry with very few limited exceptions,” Schlotterbeck, who left the helm of EQT last year, continued. “In fact, I’m not aware of another case of a disruptive technological change that has done so much harm to the industry that created the change.”

“While hundreds of billions of dollars of benefits have accrued to hundreds of millions of people, the amount of shareholder value destruction registers in the hundreds of billions of dollars,” he said. “The industry is self-destructive.”

Schlotterbeck is not the first industry insider to ring alarm bells about the shale industry’s record of producing vast amounts of gas while burning through far more cash than it can earn by selling that gas. And drillers’ own numbers speak for themselves. Reported spending outweighed income for a group of 29 large public shale gas companies by $6.7 billion in 2018, bringing the group’s 2010 to 2018 cash flow to a total of negative $181 billion, according to a March 2019 report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

But Schlotterbeck’s remarks, delivered to petrochemical and gas industry executives at the David L. Lawrence Convention Center in Pittsburgh, come from an individual uniquely positioned to understand how major Marcellus drillers make financial decisions — because he so recently ran a major shale gas drilling firm. Schlotterbeck now serves as a member of the board of directors at the Energy Innovation Center Institute, a nonprofit that offers energy industry training programs.

His warnings on Friday were also offered in unusually stark terms.

‘Destroyed on Average 80 Percent of the Value of Their Companies’

“The technological advancements developed by the industry have been the weapon of its own suicide,” Schlotterbeck added, referring to the financial impacts of shale gas drilling on shale gas drillers. “And unfortunately, the industry still has not fully realized how it’s killing itself. Since 2015, there’s been 172 E&P company bankruptcies involving nearly a hundred billion dollars of debt.”

“In a little more than a decade, most of these companies just destroyed a very large percentage of their companies’ value that they had at the beginning of the shale revolution,” he said. “It’s frankly hard to imagine the scope of the value destruction that has occurred. And it continues.”

At the Friday conference, he displayed a slide showing the stock prices of eight major Marcellus shale gas drillers: Antero, Range Resources, Cabot Oil and Gas, Southwestern Energy, CNX Gas, Gulfport, Chesapeake Energy, and EQT, the company that Schlotterbeck ran until he resigned in March 2018. Seven of the eight companies saw their stock prices fall between 40 percent and 95 percent since 2008, the slide showed.

“Excluding capital, the big eight basin producers have destroyed on average 80 percent of the value of their companies since the beginning of the shale revolution,” Schlotterbeck said. “This is not the fall from the peak price during the shale decade, this is the drop in their share price from before the shale revolution began.”

Mr. Schlotterbeck credited the shale rush with lowering power and natural gas bills nationwide and offering significant economic benefits since 2008, when he said the shale revolution began.

“Nearly every American has benefited from shale gas, with one big exception,” he said, “the shale gas investors.”

Residents of communities where shale gas drilling and fracking have caused disruptions and health issues might take exception to Mr. Schlotterbeck’s categorical description of the beneficiaries of shale gas, as might climate scientists who have warned that the shale industry’s greenhouse gas emissions are so severe that burning gas for power may be worse for the global climate than burning coal.

Only Cabot Oil and Gas, which owns the rights to drill gas from roughly 174,000 acres, mostly in one county in the northeastern corner of Pennsylvania, saw its stock price rise since 2008, according to Schlotterbeck’s presentation.

Cabot remains at the center of disputes tied to water contamination, a gas well blow-out, and other problems in Dimock, PA. One major lawsuit in that dispute was filed against Cabot back in November 2009 and legal battles have continued since. The company has denied liability and settled on undisclosed terms with landowners along Carter Road in Dimock.

Schlotterbeck made no mention of Dimock, focusing his remarks on the economic decisions made by the shale gas industry’s corporate management and boards of directors — not just in the past, but also in the present.

“The fact is that every time they put the drill bit to the ground, they erode the value of the billions of dollars of previous investments they have made,” he said. “It’s frankly no wonder that their equity valuations continue to fall dramatically.”

Slowing the Flow?

More recently, shale gas producers have begun to feel the heat from investors who are pushing to see signs that the gas can be produced not just in high volume, but also at a profit.

“As a result of investor pressure, all these companies have committed to lower growth rates and to live within cash flow,” said Schlotterbeck. He noted that the drillers had slashed their gas production growth forecasts from over 20 percent down to 11 percent this year. “Yet both the gas commodity market and the equities market are saying this is not nearly enough of a cut.”

He noted that the at-the-wellhead price of natural gas in the Marcellus region was around $8/MMBtu back in 2008, and had plunged to less than $2/MMBtu today.

That price plunge was caused by a massive glut of shale gas production as drillers raced first to hold acreage by producing gas, then competed to see who could make individual wells produce at higher rates by using tactics like drilling longer horizontal well bores and experimenting with the proppants used during fracking.

“And at $2 even the mighty Marcellus does not make economic sense,” he said, later clarifying that that included both “dry” gas wells, which produce mostly methane, and “wet” gas wells, which also produce the natural gas liquids (NGLs) that can be used by the petrochemical industry as raw materials for making plastic and chemicals. “Wet gas is better, but nobody’s making money at $2 gas.”

“Over the past year or so, most of the producers have shifted away from the phenomenal growth rates of the past to more moderate growth projections,” Schlotterbeck said. “The market is clearly telling them that they haven’t slowed down enough.”

“Now I tell you all this because I think it has long-term implications for the end users of natural gas. This situation cannot continue indefinitely,” Schlotterbeck continued. “There will be a reckoning and the only questions is whether it happens in a controlled manner or whether it comes as an unexpected shock to the system.”

Frackers Projected Returns ‘Should Not Exist’ — and Don’t

He pointed to profit predictions in a “current investor presentation” by a shale driller he did not name but described as one of the eight largest in the Marcellus. That driller, he said, presently predicts it can make a 46 percent internal rate of return by drilling their dry gas wells at current gas prices, and 61 percent internal returns from the same wells if gas prices rise 36 percent.

“Economics and common sense will tell you that in a world of abundant similar opportunities, rates of return at that level should not exist,” Schlotterbeck said. “And they don’t.”

“Really indicates to me that there’s a lot of these companies that still don’t get it,” he said. “They still think they’re gonna earn 40, 50, 60 percent returns on their investment, even after six years now of saying that and getting negative returns.”

Schlotterbeck said there was a reason he made his presentation to the petrochemical industry in Pittsburgh, where industry plans a massive construction spree to build plastics and chemical factories in large part because gas prices have fallen so sharply. In December, the Department of Energy cited the “tremendous low-cost resource from the Marcellus and Utica shales” as it announced publication of a report touting benefits from building new petrochemical infrastructure in Appalachia.

Drillers’ financial troubles could have significant implications for the petrochemical build-out in the Ohio River Valley.

“I tell you this because the current gas commodity price environment is not sustainable and higher gas prices are required for the shale revolution to continue,” Schlotterbeck said. “Exactly what prices are required for the industry to become reasonably healthy is hard to predict.”

His own personal prediction, he added, was that prices would rise 60 to 80 percent, reaching $3.50 or $4 per thousand cubic feet (mcf). And production growth will have to slow.

In response to an audience question about the impact of demand from new petrochemical plants currently planned for the region, Schlotterbeck said that for drillers, those plans were “great news on the demand side.”

“But when producers are growing 11 percent per year, I don’t think demand can keep up at that pace,” he added.

“The large gas producers will need to make further reductions in their drilling activity,” he said. “Whether they do it on their own accord or if shareholders and bondholders revolt and force them to, I think remains to be seen.”

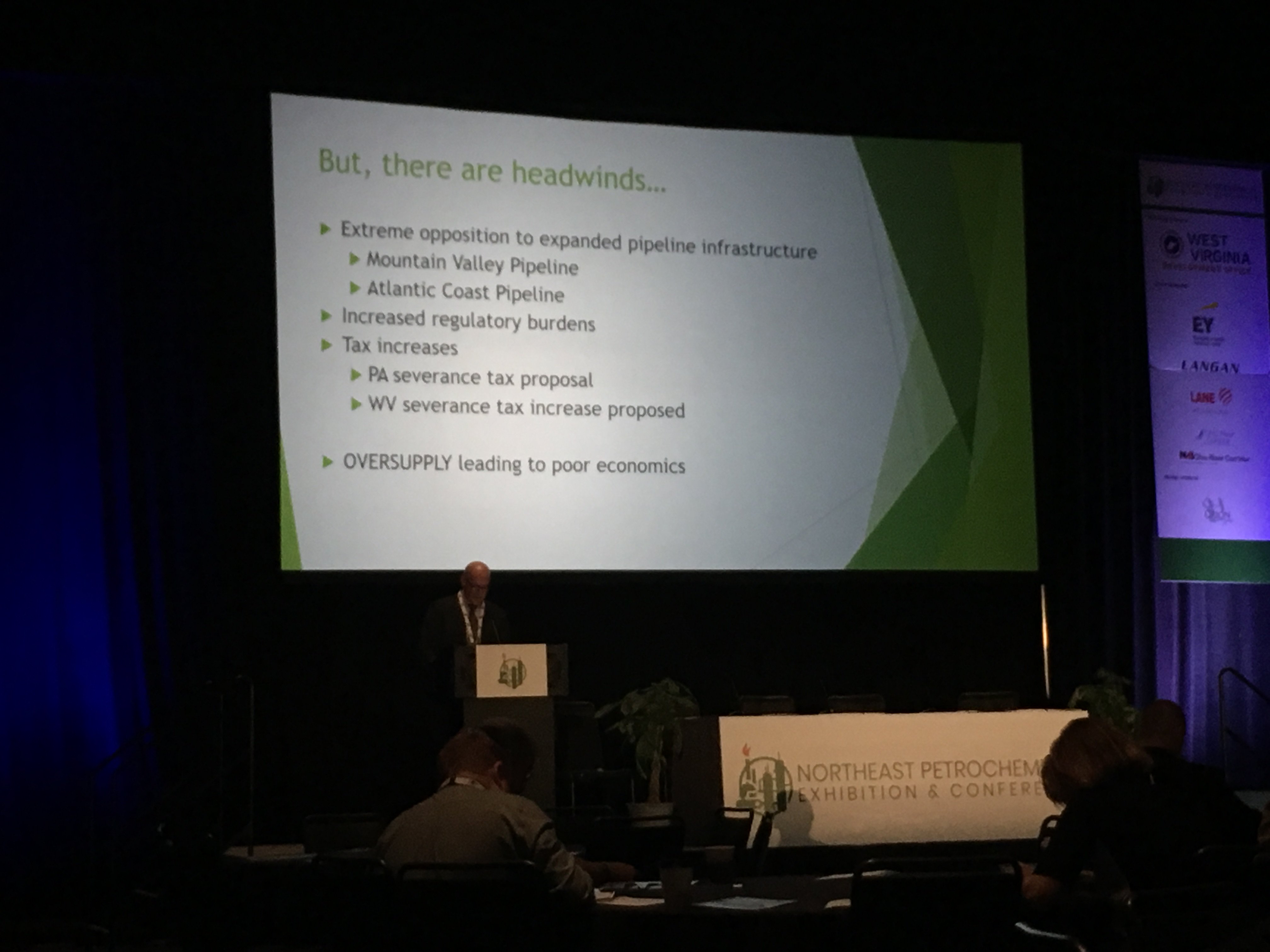

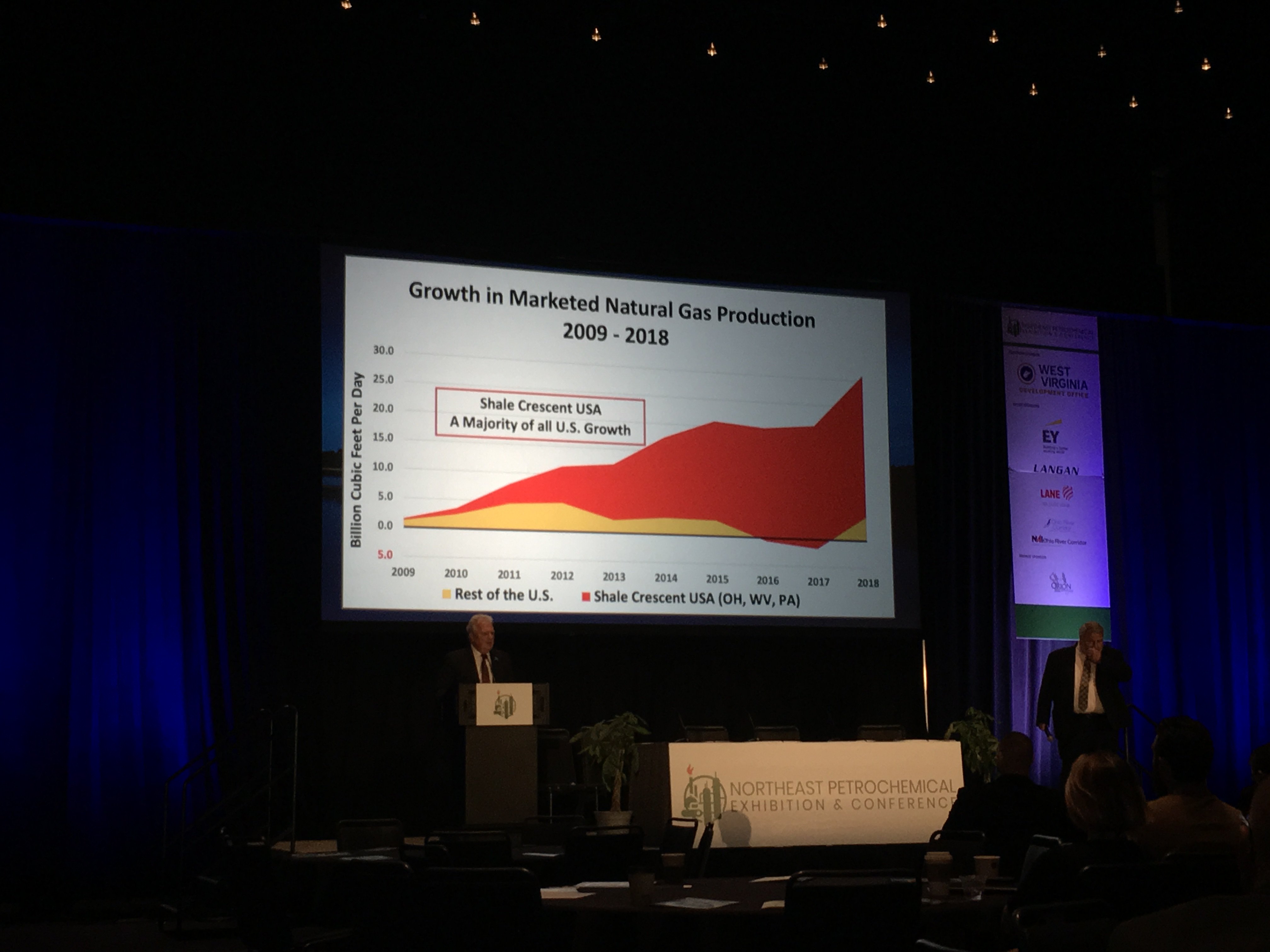

Shale Crescent USA, a petrochemical industry group pushing to transform the Ohio River Valley and Appalachia into a plastics and chemical manufacturing center to rival the one on the Gulf Coast — known locally as “cancer alley” — offered their projections, which predict production will continue to grow rapidly, in a presentation following Schlotterbeck’s.

Shale Crescent USA’s pitch to policy-makers in Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia and Kentucky and to plastics and chemical manufacturers has heavily emphasized the low cost of shale gas and NGLs in the region.

On Friday, Wally Kandel, a Solvay Specialty Polymers vice president, and Jerry James, president of Artex Oil Co., played back a video segment about Shale Crescent USA aired by Bloomberg in June 2018.

“In Shale Crescent USA, you have the most abundant natural gas, the cheapest natural gas in the developed world,” Kandel told Bloomberg in the clip.

“It was that rapid increase in production that got us to start Shale Crescent USA,” James told the conference in Pittsburgh Friday.

James didn’t take issue with Schlotterbeck’s conclusions about the shale revolution. “It’s profoundly changed the market,” said James. “It’s just absolutely amazing what we’ve been able to do.”

“We’ve achieved everything but big profits — and I agree with him,” James continued, referring to Schlotterbeck, “but for people on the downstream side [i.e. industrial consumers of shale gas and NGLs], this is revolutionary.”

In brief comments following Schlotterbeck’s remarks, Charles Schliebs of Stone Pier Capital Advisors recalled an earlier — but failed — plan to drive demand for shale gas, one heavily pushed by former Chesapeake Energy CEO Aubrey McClendon, who died in a car crash a day after being indicted by federal prosecutors with the Department of Justice over alleged bid-rigging.

McClendon, Schliebs recalled, had urged car makers to start building cars that would run on compressed natural gas, or CNG. “Aubrey had amazing plans and was spending a lot of money and doing things to push CNG in cars and in light trucks,” Schliebs recalled.

These days, CNG passenger vehicles seem more like a passing fad, overshadowed by the rise of electric vehicles. Schliebs noted that just two or three weeks before the petrochemical conference, EQT’s CNG fueling station in Pittsburgh’s strip district closed permanently and quietly, adding that he’d been told its owners had no plans to open a replacement.