Above Photo: POLITICO illustration/iStock

Once ladders of social mobility, universities increasingly reinforce existing wealth, fueling a backlash that helped elect Donald Trump.

Those criteria often serve as unofficial guidelines for some colleges’ admission decisions and financial priorities, with a deeply ingrained assumption that the more a school spends — and the more elite its student body — the higher it climbs in the rankings. And that reinforces what many see as a dire situation in American higher education.“We are creating a permanent underclass in America based on education — something we’ve never had before,” said Brit Kirwan, former chancellor of the University of Maryland system.For instance, Southern Methodist University in Dallas conducted a billion-dollar fundraising drive devoted to many of the areas ranked by U.S. News, including spending more on faculty and recruiting students with higher SAT scores — and jumped in the rankings. Meanwhile, Georgia State University, which has become a national model for graduating more low- and moderate-income students, dropped 30 spots.

Those criteria often serve as unofficial guidelines for some colleges’ admission decisions and financial priorities, with a deeply ingrained assumption that the more a school spends — and the more elite its student body — the higher it climbs in the rankings. And that reinforces what many see as a dire situation in American higher education.“We are creating a permanent underclass in America based on education — something we’ve never had before,” said Brit Kirwan, former chancellor of the University of Maryland system.For instance, Southern Methodist University in Dallas conducted a billion-dollar fundraising drive devoted to many of the areas ranked by U.S. News, including spending more on faculty and recruiting students with higher SAT scores — and jumped in the rankings. Meanwhile, Georgia State University, which has become a national model for graduating more low- and moderate-income students, dropped 30 spots.

Meanwhile, there is no measurement for the economic diversity of the student body, despite political pressure dating back to the Obama administration and a 2016 election that revealed rampant frustration over economic inequality. There is, however, growing evidence that elite universities have reinforced that inequality.

Recent studies have produced the most powerful statistical evidence in decades that higher education — once considered the ladder of economic mobility — is a prime source of rewarding established wealth. One report by the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation found that kids from the top quartile of income earners account for 72 percent of students at the nation’s most competitive schools, while those from the bottom quartile are just 3 percent. Fewer than 10 percent of those in the lowest quartile of income ever get a bachelor’s degree, research has shown.

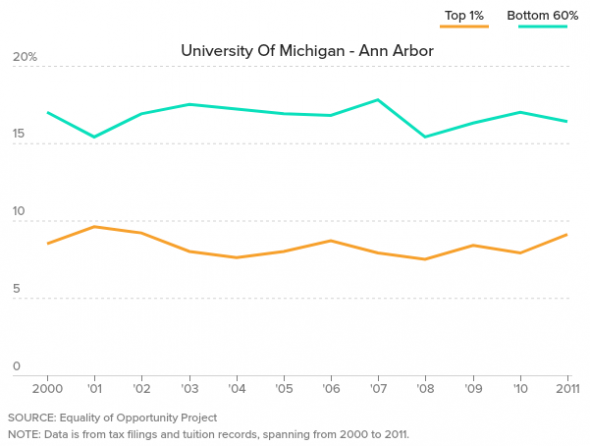

The lack of economic diversity extends far beyond the Ivy League, and now includes scores of private and public universities, according to the Equality of Opportunity Project, which used tax data to study campus economic trends from 2000 to 2011, the most recent years available. For instance, the University of Michigan enrolls just 16 percent of its student body from the bottom 60 percent of earners. Nearly 10 percent of its students are from the top 1 percent.

Class-based anger was a driving factor in the 2016 presidential campaign, as white voters without college degrees vented their frustration by voting for Donald Trump in record numbers; it was the single best statistical predictor of a Trump voter. In the wake of Trump’s election, the majority of Republicans say colleges and universities have a negative effect on the country, according to the latest polling by the Pew Research Center. Young people still see college as necessary to get a good job and move up in society. But the vast majority don’t believe the higher education system is helping them do that, according to a recent report by New America, a Washington-based think tank.

Carol Christ, chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley — perennially near the top of the rankings — said the extent to which U.S. News motivates schools to pick wealthier students is “mind-boggling.”

An elitist equation

Higher education in America is a fiercely competitive enterprise. It’s a market-based system in which status is largely based on perception — a university’s prestige has an inordinate effect on who applies and how easily students are able to get jobs with lucrative employers. And the mark of prestige, in recent decades, has been a ratings system begun by the nation’s third-largest news magazine.

Mitchell Stevens, a Stanford University sociologist who has studied college admission practices, said the U.S. News rankings have evolved into nothing less than “the machinery that organizes and governs this competition.”

“They’re kind of a peculiar form of governance,” he said. “They’re not states, they’re not official regulators, they don’t have the backing of a government agency. But they effectively serve as the governance of higher education in this country because schools essentially use them to make sense of who they are relative to each other. And families use them basically as a guide to the higher education marketplace.”

Colleges go to great lengths to rise in the rankings. The president of one school ranked in the top 20 said the college caps classes at 19 students, simply because the rankings reward schools for keeping classes under 20 students. In some states, the rankings are built into accountability systems for university presidents. Arizona State trustees put a bonus pegged to the rankings in the president’s contract. In Florida, Gov. Rick Scott set a goal to “achieve the first top-10 research public university and a second-ranked public university in the top 25.”

“The sad part is … if you care about the health of your institution, those benchmarks for the public — you have to pay attention to that stuff,” said Bridget Burns, at the University Innovation Alliance, a group of 11 colleges that has banded together to create strategies to help low-income students. “An unelected group gets to set the measures by which institutional behavior is judged and evaluated.”

The rankings aren’t meant to hold such sway, U.S. News officials say.

“We’re not setting the admissions standards at any schools,” said Robert Morse, chief data strategist at U.S. News who develops the methodologies and surveys for the rankings. “Our main mission for our rankings is to provide information for prospective students and their parents, and we’re measuring academic quality. That’s what we’ve been doing. We’ve been doing this for 30 years, and we believe we’ve been driving transparency in higher education data. Our methodology and the data we’ve chosen for the best colleges rankings is to measure which schools are the top in academic excellence.”

The rankings are based on a formula of 15 weighted criteria that Morse says, taken together, provide a good look at the academic quality of the nation’s schools. He stressed that outcomes — the rates at which schools are able to graduate students and keep them coming back year to year — are the most important part of the formula. They make up 30 percent of the total.

How U.S. News ranks schools

“There’s no perfect indicator and there’s no perfect ranking,” Morse said. “Anybody who does rankings is making choices on which indicators to use, and more or less each indicator — people can criticize it in some way. We believe when you aggregate the 15 indicators we’re using, we’re coming up with a very good measure of a school’s relative standing.”

“There’s no perfect indicator and there’s no perfect ranking,” Morse said. “Anybody who does rankings is making choices on which indicators to use, and more or less each indicator — people can criticize it in some way. We believe when you aggregate the 15 indicators we’re using, we’re coming up with a very good measure of a school’s relative standing.” Many college presidents are skeptical about the tests’ effectiveness, but feel obliged to pay attention to student scores anyway to protect their rankings.

Many college presidents are skeptical about the tests’ effectiveness, but feel obliged to pay attention to student scores anyway to protect their rankings.

Eric J. Furda, Penn’s dean of admissions, said in a statement that “there is an outdated notion that early decision serves a narrow group of students, which simply does not hold true at Penn . . . The early decision pool is deeper and broader than it has ever been given the strength of our grant-based financial aid, our extensive recruitment and outreach efforts and the quality of the Penn undergraduate experience and educational outcomes.”

Some colleges have given faculty raises with the sole purpose of boosting their U.S. News ranking, Stevens, the sociologist who is now at Stanford University, said. When he was on the faculty at a small liberal arts college in the 1990s, the entire faculty was given a 15-percent raise overnight. They were told it was to improve the school’s ranking.

“It was a relatively straightforward mechanism for boosting rankings,” Stevens said.

Kirwan, the former University of Maryland chancellor, put it this way: “If you could deliver the same quality at lower cost, you’d go down in the rankings.”

Likewise, an easy way for universities to jump in the rankings is simply to raise tuition and increase spending. Baylor University, a private Christian school in Texas, wrote into its “Baylor 2012” strategic plan in 2002 a goal of breaking into the top 50 schoolswithin 10 years. It poured hundreds of millions into programs and faculty salaries and was ranked 75 by 2012, according to the 2014 report. It then jumped to 71 in the 2017 rankings, published last September.

But such spending can also push up tuition. In 2002, Baylor charged $17,214 a year in tuition and fees. That has soared to $44,040 this year. The university said in a statement that “while rankings in national publications and acknowledgements by outside organizations are certainly desirable, they were not the primary objective of ‘Baylor 2012’ and its related expenditures.”

— Alumni giving rate (5 percent). Per U.S. News: Giving is an indirect measure of student satisfaction; students are more willing to contribute to their alma mater if they felt like they received a good education there. But elite colleges have a long history of catering to children of alumni to keep the donations flowing. More than 40 percent of Harvard’s class of 2021 are legacy students — meaning they have family members who attended before them, according to data compiled by the Harvard Crimson. This hurts the chances of lower-income applicants who are often the first in their families to go to college.

— Graduation and retention rates (22.5 percent) and graduation rate performance (7.5 percent). This is the portion that is actually the most helpful to lower-income students. Schools are rewarded for graduating more students. And U.S. News gives special credit to schools that do a better job of graduating low-income students.

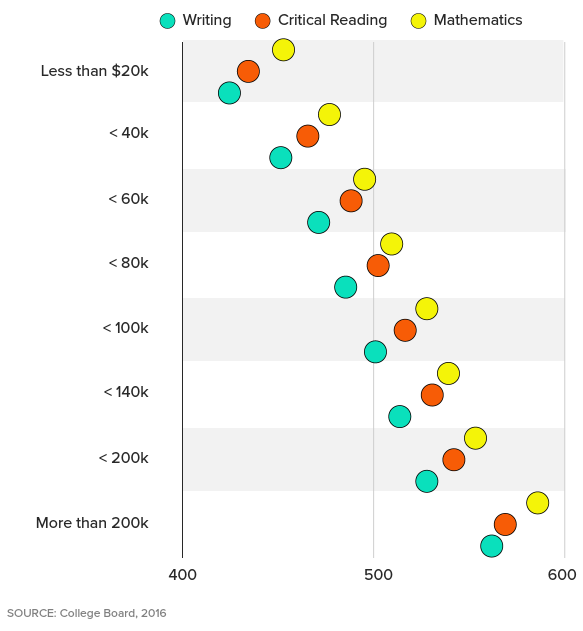

But the measure can also work to the advantage of schools with fewer low-income students. Most universities near the top of the rankings have a high proportion of well-off students, who don’t face financial pressures that might lead them to drop out. College Board data indicate that students in the top income quartile graduate at about a 13-percentage-point higher clip than those in the bottom quartile. The gap in degree attainment also appears to be growing. According to a University of Pennsylvania study, students from families in the top half of income earners accounted for 77 percent of bachelor’s degrees in 2014 — up from 72 percent in 1970.

Nonetheless, to U.S. News’ credit, the graduation rate performance measure — which controls for factors like test scores and income — is one of the only portions of the ranking formula that recognize schools that are working to help the most disadvantaged students. U.S. News controls for student characteristics, like how many of them are on Pell Grants, which go to lower-income students, and predicts what a school’s graduation rate should be. If the actual rate is higher, U.S. News deems the college is “enhancing achievement, or over-performing,” and it gets a boost.

It’s a recent addition to the rankings formula, and, while lauded by presidents and administrators, it’s still just a sliver of the equation.

U.S. News defends the entire formula. Morse argues that if schools are seeking to improve in the U.S. News rankings, they’re probably becoming better institutions in the process.

“If they’re improving graduation rates and doing a better job of retaining students, or they’re investing money to have more small classes and fewer large classes, and they’re hiring better faculty with better credentials, then they’re creating a better academic environment,” Morse said. “If a school wants to rise in our ranking, it’s not by rejecting more students … You have to make improvements across the board. The schools that have risen in the ranking have done so by making improvements across the board.”

Rewarding the rich

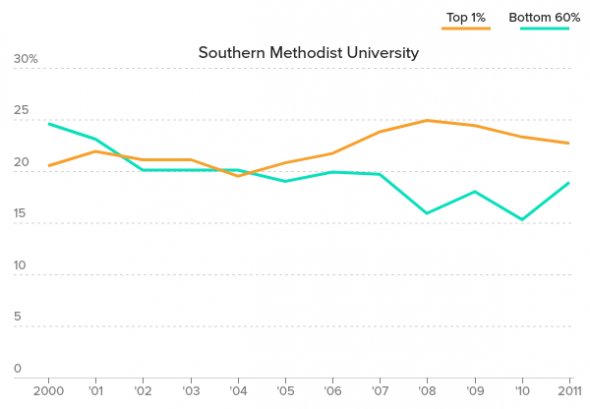

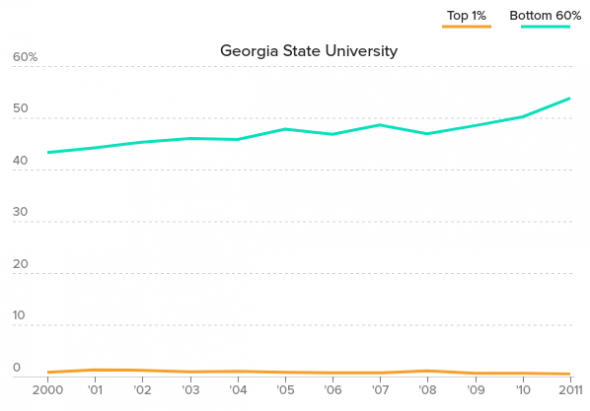

Nonetheless, the sometimes spurious nature of the rankings can be measured in the experience of two universities — Georgia State and Southern Methodist — and their seesawing fortunes from 2008 to 2016.

Georgia State, which dramatically improved both its economic diversity and its graduation rate, nonetheless plummeted in the rankings. SMU, which conducted a major fundraising campaign powered by unusually high levels of alumni giving, saw its fortunes soar, even though its student outcomes were largely unchanged.

At Georgia State, administrators made a conscious decision to reduce emphasis on SAT scores to build a more diverse student body because administrators found that scores didn’t actually predict how well a student would do. High school performance is a better indicator, administrators and studies say. “Basically, if you’re a B student, we’ll admit you,” said Timothy Renick, vice provost at Georgia State.

The average SAT score has dropped 33 points.

At the same time, Georgia State has nearly doubled its number of students on Pell Grants, who now make up about 60 percent of its student body. The school enrolls more students on Pell Grants than any other public research university, and more than the entire eight-university Ivy League — by a nearly 3-to-1 margin.

The school is serving more of the middle class, as well. According to the Equality of Opportunity Project data, the percentage of students from the bottom 60 percent of income earners rose by 11 percentage points from 2000 to 2011, the most recent year statistics are available, to 54 percent. The percentage of students from the top 1 percent — which never made up a significant portion of Georgia State’s student body — has shrunk, as well, from just under 1 percent in 2000 to just half a percent in 2011.

But at the same time, the school has fallen 30 spots in the rankings.

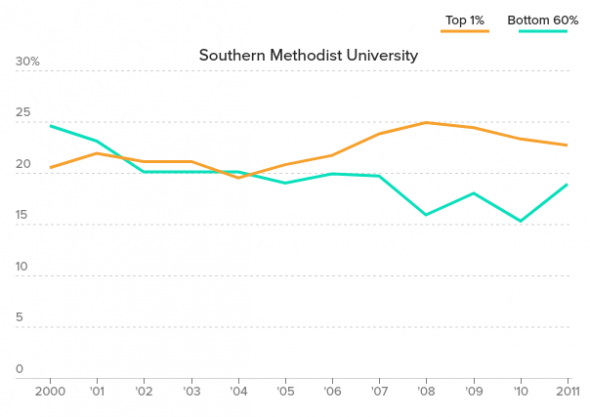

But as it celebrates its increase in the rankings, SMU has catered more to the elite. According to the Equality of Opportunity Project data, the top 1 percent made up 23 percent of SMU’s student body in 2011, the most recent year statistics are available. Students from the bottom 60 percent made up just 19 percent. It’s a mirror image of the student population in 2000, when the bottom 60 percent made up 25 percent of the student body and the top 1 percent was 20 percent.

SMU officials say they’re working to reverse the trend, including spending some of the money the school raised in its billion-dollar campaign on need-based aid for low-income students. The school also has a program that offers micro-grants to low-income high school students.

SMU officials say they’re working to reverse the trend, including spending some of the money the school raised in its billion-dollar campaign on need-based aid for low-income students. The school also has a program that offers micro-grants to low-income high school students.

’Shaking your fist at the gods’

The lack of economic diversity in higher education, and the rising cost of college, are among the few issues on which the Trump administration and the Obama administration share common ground. Obama repeatedly complained about excessive spending by universities in his State of the Union addresses, to little avail. He also blasted the college ranking system, which he said “actually rewards [colleges], in some cases, for raising costs.” The Obama administration launched its own ratings system, the College Scorecard, in part to counter U.S. News’ rankings.

The College Scorecard appears to be among the few Obama initiatives that Trump will continue. The new administration plans to release the latest round of ratings later this fall, an Education Department spokeswoman said.

But college presidents and administrators say creating a counter-rating to U.S. News isn’t enough to force changes on campus — and the scorecard drew a fair share of criticism upon its initial launch, with a messy rollout and questions over data quality.

Some colleges — including some in the Ivy League and some state flagships — have started alliances aimed at finding ways to recruit and retain more low-income students.

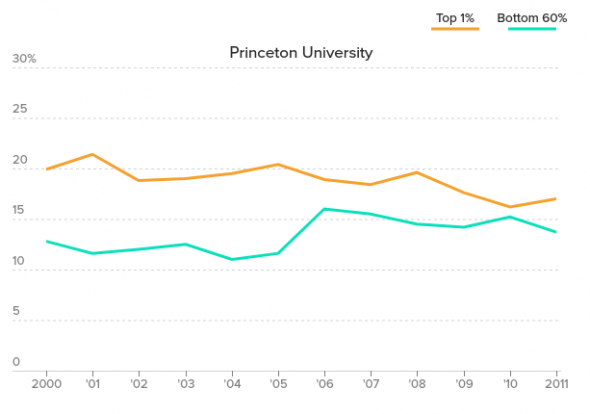

One, the American Talent Initiative, includes 30 colleges, all with a six-year graduation rate of at least 70 percent. Among the group’s leaders are the presidents of Princeton, the University of Washington and Ohio State.

Another group, the University Innovation Alliance, is made up of 11 major public research universities — including Georgia State, Purdue and the University of Texas at Austin — that share strategies for improving economic diversity. For example, Georgia State’s micro-grant program — through which the school automatically deposits aid to students at risk of dropping out — will be adopted by all 11 schools, the alliance announced earlier this summer.

Congress is also starting to weigh in. House Republicans have suggested that wealthy colleges need to dip more into their massive endowments to help low-income students.

Rep. Tom Reed (R-N.Y.) has pushed a plan that would require universities with endowments exceeding $1 billion to spend at least a quarter of their investment income on financial aid to maintain their tax-exempt status. Any university eligible for tax-exempt donations would be required to disclose more information about salaries and amenities, and colleges would need to file “cost-containment plans” to make sure tuition increases don’t outpace inflation.

The Senate Finance and House Ways and Means committees last year ratcheted up the pressure with a joint letter to 56 private colleges and universities with over $1 billion in endowment inquiring about how they “are using endowment assets to fulfill their charitable and educational purposes.”

There is little they can do to influence U.S. News to change its system. When college leaders complain, they get invited to U.S. News headquarters in Washington. There, editors let them air their complaints. Then, according to college presidents, the editors often tell them what they need to do to move up in the rankings: Spend more on faculty, admit better students, etc.

“I’ve worked with 29 presidents and chancellors and that story has been relayed to me by multiple campus leaders,” said Burns of the University Innovation Alliance. “When they sit down with you, you think hopefully you’ll be able to influence these mechanisms. Instead, they will tell you how to move up.”

Brian Rosenberg, president of Macalester College, said he met with U.S. News officials and raised concerns that the rankings incentivize schools to spend more money when the cost of college is already skyrocketing.

“The question I asked was, ‘Doesn’t this seem to run counter to what’s really in the public’s interest?’” he recalled.

“The answer was, ‘Yes, we know it — but we don’t care.’”

Morse, of U.S. News, denied that, saying, “We do meet regularly with college presidents and admissions deans and we’re definitely aware of what’s written about U.S. News.”

To many presidents, though, prodding U.S. News to change feels like a lost cause.

Said Rosenberg, “It feels a little bit like shaking your fist at the gods — there’s nothing I can do about it.”