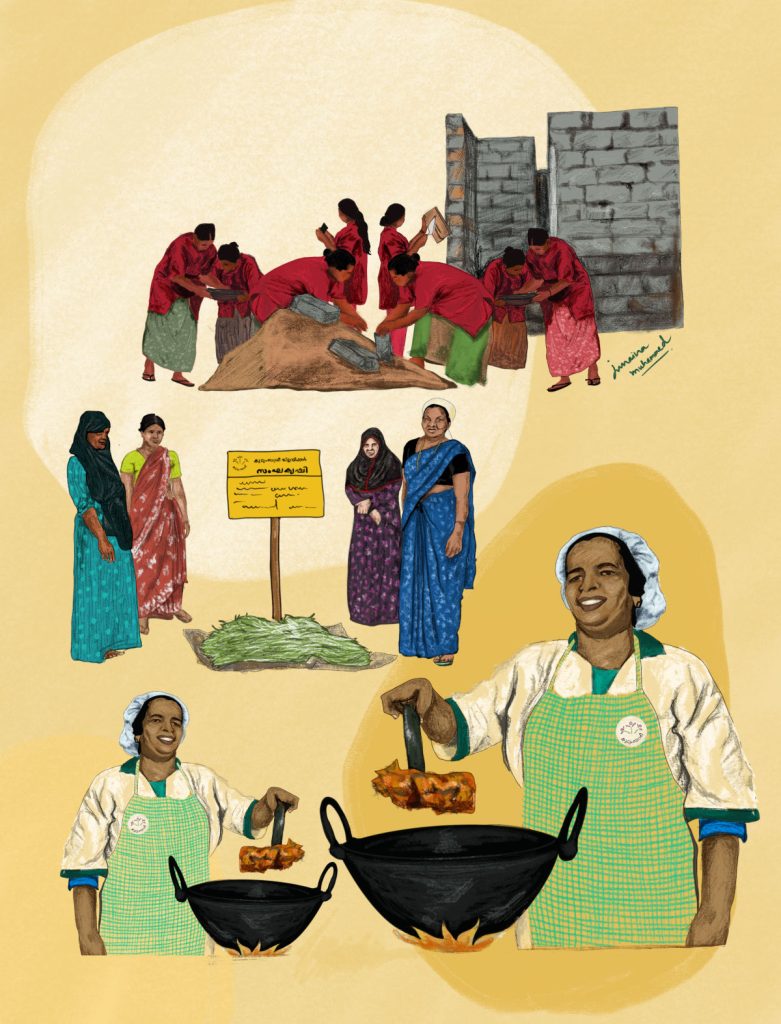

Above photo: Junaina Muhammad (Young Socialist Artists), Kudumbashree, 2025.

The Indian state of Kerala has eradicated extreme poverty through clear public policy, decentralised planning, and the leadership of its cooperative movement.

On 1 November 2025, the south-western Indian state of Kerala – home to 34 million people – was declared free from extreme poverty by Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan. Kerala is one of the few places in the world to have eradicated extreme poverty, following China, which announced in 2022 that it had eradicated extreme poverty nationwide.

Kerala’s achievement is significant for two reasons. First, in a country where hundreds of millions of people still live in poverty, Kerala is the only one of India’s twenty-eight states and eight union territories to have overcome extreme poverty. Second, Kerala is governed by the Communist-led Left Democratic Front (LDF) and is therefore routinely denied assistance from the central government led by the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (Indian People’s Party).

Kerala’s Athidaridrya Nirmarjana Paripaadi (Extreme Poverty Eradication Project, or EPEP) was built on decades of worker and peasant struggles, which created strong public institutions and mass organisations, and the work of several left administrations. The EPEP was launched by Vijayan – a leader in the Communist Party of India (Marxist) – during the first Cabinet meeting of the second LDF government led by him in May 2021. After a rigorous criteria-based process focused on households’ access to employment, food, health, and housing, the government identified 64,006 families (or 103,099 individuals) as extremely poor. To carry out this survey, the government relied on about 400,000 enumerators – including government workers, cooperative members, and members of the mass organisations of left parties – to identify the unique problems faced by poor families. These enumerators created tailored plans for each family – from securing entitlements and accessing public services to obtaining housing, health care, and livelihood support – to build their strength in the fight against poverty. The role of the cooperative movement was fundamental in this campaign. The planning process for poverty eradication would not have been possible without the role of the local self-government system, the result of Kerala’s successful decentralisation of power. As this newsletter goes out, Kerala is in the midst of new local body elections.

Over the past few years, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research has worked closely with the Uralungal Labour Contract Cooperative Society (UL) Research Centre to build knowledge about the cooperative movement in Kerala. We are very proud to publish our joint study The Cooperative Movement in Kerala, India within a month of Kerala’s declaration of eradicating extreme poverty. Our study profiles six different cooperatives, with essays researched and written by scholars who have worked closely with them. One essay focuses on Kudumbashree, an all-women cooperative with nearly five million members, which played a major role in implementing the EPEP.

Kerala’s first democratic government, which came into office in 1957, was led by communists. It immediately began to execute a programme of agrarian reform, including land redistribution, and to expand universal social goods such as public education, health care, housing, and libraries. This democratisation of the rural landscape, combined with sustained social mobilisation, hastened the journey of Kerala’s millions towards social indicators that are the marvel of the world: near-total literacy, very low infant and maternal mortality, high life expectancy, and some of the highest human-development scores in India. These investments, built over decades, created the conditions for poverty eradication long before the targeted programmes emerged. Communist-led coalitions have governed Kerala from 1957–1959, 1967–1969, 1980–1981, 1987–1991, 1996–2001, 2006–2011, and 2016 to the present. Even when the left was not in power, social mobilisation by the left ensured that right-wing governments could not fully reverse these gains.

With the growth of the neoliberal debt-austerity model in the 1990s, pressure grew on the LDF government to reverse some of these projects and adopt privatisation. However, the LDF chose a different path. Through the People’s Plan Campaign for Decentralised Planning, launched in 1996, the government devolved 40% of state expenditures to local governments and asked localities to identify needs, design programmes, and allocate budgets for development projects. Rather than develop a one-size-fits-all development and poverty alleviation agenda, the people of Kerala built locally planned and context-specific projects that focused on the emancipation of exploited and marginalised communities, including Adivasis, Dalits, and coastal communities. The campaign set in place a culture of democratised social policy and nourished a dense network of public institutions and cooperatives – all of which were crucial for the EPEP.

When he announced the end of extreme poverty in Kerala, Chief Minister Vijayan presented the EPEP as a continuation of this long trajectory. He highlighted several initiatives that had paved the way for the programme, including the universalisation of the Public Distribution System, which provides subsidised food and fuel, and long-term efforts to eradicate landlessness and homelessness, including the LIFE Mission, which has provided homes to well over 400,000 families across the state. To these we can add other pillars of Kerala’s model – state schemes that have expanded public health care, food distribution, educational assistance, and employment opportunities, and indeed the cooperatives. Together these initiatives have transformed social life in Kerala and strengthened the character of its left movement.

Our study with the UL Research Centre provides a window into the various cooperatives that have played a key role in the democratisation of Kerala’s economy. Formed in 1998 as part of the state’s poverty eradication mission, Kudumbashree, which means ‘prosperity of the family’ in Malayalam, is now the largest women’s mutual aid network in the world. It is built around a transformative idea: if women at the household and community level build their confidence and capacity to assess economic life, then the locus of development can shift from patriarchal institutions towards working women’s needs. Collective farms, community kitchens, cooperative skill development initiatives, and other forms of joint enterprise have allowed the women of Kudumbashree to increase their income and build power in both public and private life. Kudumbashree’s emphasis on solidarity rather than competition and on collective rather than individual entrepreneurship sets it apart from market-centric poverty-alleviation strategies. Recently, the government of Kerala announced a Women’s Security Scheme based on the necessity of recognising the value of unpaid household work. Eligible women between the ages of 35 and 60 will receive ₹1,000 per month. Such an initiative is part of the overall attempt to transform patriarchal property relations in Kerala.

Kudumbashree is part of a wider ecosystem of cooperatives that sustain Kerala’s fight against poverty. Taken together, these initiatives are powerful examples of how, in Marx’s words, ‘hired labour is but a transitory and inferior form, destined to disappear before associated labour plying its toil with a willing hand, a ready mind, and a joyous heart’. They show that cooperatives are not only safety nets for the poor but also vehicles for democratic planning, technological advance, and social dignity.

These include:

-

The Uralungal Labour Contract Cooperative Society (UL). Founded in 1925 in northern Kerala as a mutual aid society for construction labourers facing caste-based exclusion, UL has grown into one of Asia’s largest workers’ cooperatives, employing tens of thousands in major infrastructure projects. It shows how worker-controlled enterprises can deliver complex public works while expanding social protection and collective welfare for its workers and the surrounding community.

-

Kerala’s network of credit cooperatives. More than four thousand credit cooperatives, with tens of millions of mostly working-class and marginalised members, operate as ‘people’s banks’ that reach areas private finance will not. By protecting borrowers from moneylenders, anchoring land reform, and mobilising local savings – including during the 2018 floods and the COVID-19 pandemic – they provide the financial backbone for poverty eradication.

-

The Kerala Dinesh Beedi Workers’ Central Cooperative Society. Formed in 1969 after private beedi (a thin, hand-rolled cigarette) factory owners shut down their workplaces rather than implement new labour protections, Dinesh Beedi quickly became the leading beedi producer in southern India. It secured higher wages, social security, and a rich cultural life for its members, and later diversified away from tobacco to preserve jobs in socially useful production.

-

The Sahya Tea Cooperative Factory. In Idukki’s hill country, small tea growers and agricultural workers used the 15,000-member Thankamany Service Cooperative Bank to establish their own factory in 2017 and break from ‘Big Tea’ monopolies. Processing 15,000 kilograms of leaves a day and employing more than 150 workers, Sahya secures better prices for around 3,500 growers and demonstrates how small producers can move up the value chain and defend dignified livelihoods.

-

The Udayapuram Labour Contract Cooperative Society. In Kodom Belur, a remote panchayat in Kasaragod, villagers facing feudal landlordism, corrupt officials, and predatory contractors organised a labour cooperative in 1997. From just over two hundred members it has grown to nearly three thousand worker-members, including many Adivasis, who now execute public works on transparent, fair terms and shape local development priorities themselves.

Taken together, these cooperatives – alongside Kudumbashree – show what becomes possible when state policy, social reform, and organised workers converge. They do more than soften the blows of the market. They reorganise production around human need, deepen democracy in the workplace and the village, and offer a living glimpse of associated labour in practice – of possible communism – even under the harsh conditions of contemporary capitalism that make programmes like the EPEP necessary.

Kerala’s poverty eradication story is not without challenges. The state is still within the Indian Union and therefore vulnerable to the vicissitudes of policy-making by the right-wing government in New Delhi. Like many parts of the Global South, Kerala’s youth face high unemployment and often migrate to the Persian Gulf region and other parts of the world for work. Attempts to build new quality productive forces that could allow the state to leapfrog outdated industries are held back by limited access to tax revenues collected from the state by the central government. Nonetheless, there are ongoing attempts to overcome these limitations and build a more robust growth paradigm for Kerala.

In February 2021, President Xi Jinping announced that nearly 99 million Chinese people had lifted themselves out of extreme poverty, the last of the country’s impoverished. The country of 1.4 billion people did this a decade in advance of the date set by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for 2030. Kerala achieved its goal a year before expected. Vietnam, another country close to this achievement, plans to end extreme poverty by 2030. It is no surprise that all three of these projects are led by communist parties, whose commitment to human emancipation drives them to work to ensure that every human being can live a dignified life. Poverty eradication is not an end in itself but a part of the long journey for human emancipation – it is a living social project, not a set of boxes that must be ticked off. As Kwame Nkrumah said, ‘forward ever, backward never’.