Above photo: The Cradle.

With France ejected and its president in exile, Madagascar’s revolt opens the island to new suitors.

And new conflicts, in a sea increasingly shaped by multipolar ambitions.

After weeks of protests and a mutiny, former Madagascar president Andry Rajoelina boarded a French military plane and fled the country. With a public angry at a corrupt, western-aligned government, Madagascar has the potential to shape its future and the whole Indian Ocean.

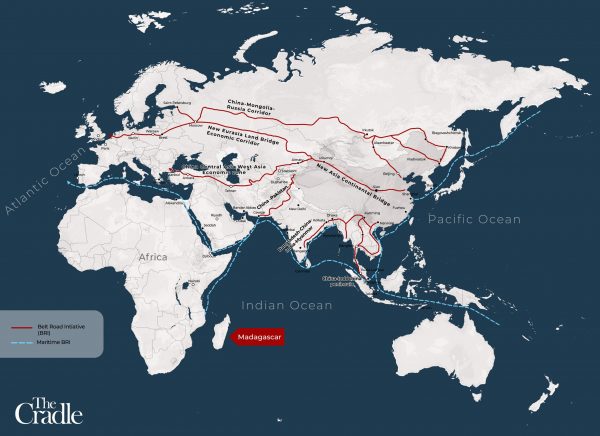

This development comes as global powers scramble for strategic access in a region that holds five of the world’s nine maritime chokepoints. India, China, and the US are expanding their naval and commercial footprint, while France – once the uncontested gatekeeper of these waters – finds itself besieged and in retreat.

As the fourth largest island in the world and, according to the CIA, “the largest, most populous, and most strategically situated of the southwestern Indian Ocean”, Madagascar is a key player, as shipping routes change and expand, and superpowers look to increase their influence.

France’s long imperial shadow

France’s colonial grip on Madagascar began in 1892, intended to counter British sway over Indian Ocean routes. Despite the Suez Canal’s opening, the Cape Route, which rounds Madagascar and the Cape of Good Hope, remained a vital artery for trade between Asia, Europe, and the Americas.

Madagascar formally gained independence in 1960. Yet decolonization remained incomplete. Paris retained control of the surrounding Scattered Islands (Les îles éparses), granting itself exclusive economic zones encircling Madagascar’s north, east, and west.

Antananarivo claims these islands under the international law of territorial integrity. In 1975, Madagascar became a socialist state and kicked the French military out. Facing growing protests over food shortages, Madagascar pivoted to a mixed economy and increased cooperation with Paris, letting the French navy dock at two ports.

Each time Malagasy leaders pivoted away from Paris, crisis followed – often ending with exile and regime change.

When protests grew in 2002, former president of Madagascar Didier Ratsiraka fled to France. The next government would be short-lived. In 2009, sections of the military mutinied and Andry Rajoelina, mayor of Antananarivo, became president – a post he held onto, until last week.

Another Francafrique collapse?

Rajoelina first rose to power in 2009 with backing from elite military units like CAPSAT. Initially presenting himself as a populist, he was removed in 2013, only to return in 2018 under a technocratic, pro-business veneer. His presidency brought little progress: Madagascar languished among the lowest global rankings for electricity and clean water access.

Corruption scandals further damaged his credibility. Instead of reforming the state-run energy monopoly, Rajoelina struck a deal giving France a 37.5 percent stake in a major dam project – even as he postured about reclaiming the Scattered Islands. Revelations of his secret French citizenship undermined this nationalist stance, especially given Madagascar’s ban on dual nationality.

When nearly two dozen protesters were killed last month, CAPSAT turned on him. The military that had once elevated Rajoelina now removed him. His flight to France echoes the collapse of other western-backed leaders across the continent.

Paris, cornered in Africa

Madagascar’s uprising is only the latest chapter in France’s broader retreat from Africa. The French military has been expelled from Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Central African Republic, and others. It now clings to token deployments of fewer than 200 soldiers in Gabon and Djibouti – the latter already hosting seven other foreign bases.

In January 2022, Burkina Faso underwent a coup after the government failed to stop the ISIS and Al-Qaeda insurgency. When nothing changed, another coup followed in September, led by the anti-imperialist Ibrahim Traore. In Mali, a 2020 coup was followed by another in 2021 by the more radical Assimi Goita.

The loss of Madagascar carries enormous strategic cost. The French-occupied Scattered Islands straddle the Mozambique Channel. In addition to the channel facing growing piracy risks amid an Islamic insurgency in Mozambique, it is a key transit route whose importance has surged as Red Sea trade routes face disruptions from Yemen’s blockade imposed by the Ansarallah-aligned armed forces. Shipping traffic around the Cape Route has increased by over 200 percent.

Paris risks losing control of the very maritime chokepoints it once colonized to secure. The recent return of the Chagos Islands to Mauritius by the UK further isolates France as the last colonial power resisting decolonization in the Indian Ocean.

India and China circle the vacuum

India, whose economy depends on the Indian Ocean for 90 percent of its trade, has been quietly building its presence for decades. In 2007, it established a listening post in northern Madagascar.

This was soon followed by other military installations in the western Indian Ocean, including Mauritius, the Maldives, Oman, and the Seychelles.

In 2018, India and Madagascar signed a defense cooperation agreement, and imports and exports with India doubled from 2012 to 2022. A larger presence in Madagascar would allow India to foster closer trade, protect trade routes and create an early warning system for hostile vessels entering the Indian Ocean.

New Delhi’s interest is both strategic and economic: safeguarding trade routes, monitoring rival navies, and extracting mineral wealth. Nickel – vital for electronics and defense manufacturing – is abundant in Madagascar, but its extraction has been limited by poor infrastructure.

China, meanwhile, sees the Indian Ocean as the maritime spine of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Around 80 percent of China’s oil imports flow through these waters. To secure its interests, China built a military base in Djibouti in 2017 and is expanding ports in Eritrea, Kenya, Madagascar, Mozambique and Sri Lanka.

While Beijing has focused more on East Africa, it is poised to expand its influence in Madagascar. It already invested in the Tamatave port and could now push for access to Diego Suarez – a former French naval base.

Despite being Madagascar’s top trading partner, China has treaded lightly in political affairs. That may change. A new government in Antananarivo presents an opportunity for Beijing to deepen its hold on a corridor essential to its global ambitions.

Washington’s late and limited game

The US has lagged behind in this contest, constrained by geography and distracted by wars elsewhere. Until recently, Washington’s main concern in the Indian Ocean was West Asia, ensuring the flow of oil and other goods through the Persian Gulf and Red Sea.

But just as France once feared Britain would monopolize the Indian Ocean, America now worries China will do the same. Even Russia has made more of an effort, backing candidates in the 2018 Madagascar election, opening a base on the Red Sea in Sudan, doing joint drills with Myanmar, and working with India to create a Chennai–Vladivostok maritime route.

Its Indo-Pacific strategy – a rebranding of its Asia–Pacific pivot – has yielded limited gains. Tariff wars with India and a light military footprint in the western Indian Ocean have stymied Washington’s ambitions.

Nevertheless, the US remains Madagascar’s largest export destination. And it could see in Madagascar what France once saw: a launchpad to counter rivals.

But a history of bad relations, including the cutting of aid after the 2009 coup and recent tariffs, will make reestablishing relations difficult – and impossible if the new Malagasy government actually becomes anti-imperialist.

Revolutionary promise or neocolonial reset?

The only way the US can gain a foothold is if it can co-opt the Malagasy revolution, turning the ruling military into puppets of western interest. It was done in the Arab Spring and it can be done again.

But Africans no longer have patience and are willing to do what is necessary to keep the west out, as they did in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. Perhaps aware of this, the new Madagascar President, Michael Randrianirina, signalled his anti-imperialism when he refused to speak French to the BBC because he “does not like glorifying the colonial tongue.”

On his first day in office, adorned with a military beret (similar to Traore’s) he went straight to a power station to tackle outage issues. Symbolic or sincere, the gesture signals an intent to address local grievances rather than foreign expectations.

If this moment holds, Madagascar could reclaim its stolen islands, extract its own resources, and chart a path independent of foreign tutelage. In doing so, it would join a growing chorus of African nations rejecting the west’s declining hegemony.

In the broader struggle for the Indian Ocean, the Malagasy revolt may well mark the beginning of the end for colonial-era arrangements – and the opening shot of a new geopolitical era.