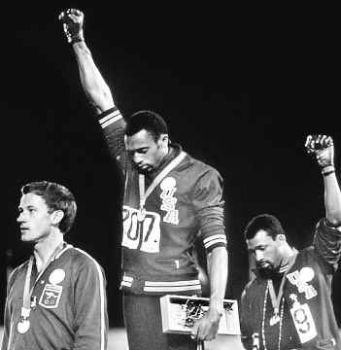

Above Photo: From PopularResistance.org.

Every year around this time, Americans shower Martin Luther King, Jr. with love. Since 1986 his birthday has been a national holiday, providing all of us with a chance to learn more about him. School kids get exposed to the nature of African American life under apartheid in the South; symposia and talks are given discussing King’s legacy; King’s experiences are examined under the lens of current racial tensions; stores can have MLK Day sales; and the marketing opportunities are endless.

Get your “I Have a Dream” fortune told at a 1-800 number; make a cake with “Batter from a Birmingham Jail”; drink an “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop Dew”; if you’re lost, use the “Where Do We Go From Here” GPS; play in the “Edmund Pettus Bridge Tournament”; get a lottery ticket for the “SNCC Six” game, where you win if you rub off the names of a half-dozen leaders of the sit-in movement . . . and so it goes on. (As I write this, a TV ad has just come on for the “Joseph A. Bank Martin Luther King Day Sale” and I’ve learned that ESPN is airing a national MLK Day Special Edition NBA game).

Surely King deserves as much recognition as possible. He gave his life for the cause of civil rights and that legacy remains vital to discussions of race in the U.S., now more than any time in the past several decades in the aftermath of Ferguson, Baltimore, and hundreds of incidents of cops killing African Americans.

But national holidays serve another purpose as well—instilling a sense of national pride and, if needed, obscuring the past. We celebrate Christopher Columbus Day even though he perpetuated a genocide (a difficult reality to accept even for a proud Sicilian-American). King’s birthday has a political purpose as well. By celebrating it, the country engages in a weekend of self-congratulation and pride over its triumph over racial separation and violence.

We can pay tribute not just to the triumph of King and his associates but to the national consensus that developed, at least north of the Manson-Dixon Line (as Gil Scott-Heron called it), that segregation had to end and civil rights had to be extended to all Americans. We hail the victory of inclusion over apartheid. Whites can feel good about their open-mindedness and African Americans (to a much greater degree than Italians and Sicilians celebrating Columbus Day), can be proud that one of their icons, actually the icon, reached the historical mountaintop and is recognized as one of the greatest Americans ever.

But MLK Day also enables us to avoid a lot of uncomfortable truths, and that’s the point often of honoring someone or making his/her life an “official” celebration (Pete Seeger always pointed out that “The Internationale” was ruined when it became the anthem of the Communist movement). With Martin Luther King Day, whites can feel good about their open-mindedness and commitment to social justice, and African Americans can be proud that the civil rights movement led to acceptance within the American system. Martin Luther King Day, then, has become not just a commemoration of the struggle of African Americans but a celebration of the market as Blacks became full participants in American capitalism, and businesses big and small can use that hook to bring in consumers during the third weekend of January every year. King, who was often violently repressed in life, has been commodified in death.

Lost in the observance of MLK’s life is the reality of many of his views, in particular his opinions on the economy, equality, war, and the need for militant action against the state and its ruling class. MLK embodied all the traits we honor on his day, but, unknown to most and certainly not celebrated, he offered a caustic, biting, and often radical critique of American society and politics, especially directed at those who ran the country and its economy. It’s not in the interests of many people to discuss the entirety of King’s life. King’s attention and focus on class issues was a challenge to the class of oligarchs that ruled America. But in many ways, it defined what he did almost as much as his commitment to civil rights. In four key areas, below, MLK offered a direct challenge to the state and ruling class on issues other than race in the south: the economy, the Vietnam War, the Olympics, and Poverty.

Democratic Socialism. In the 1950s King told his fiancée Coretta Scott, “I imagine you already know that I am much more socialistic in my economic theory than capitalistic.” Such views were not simply a product of youth, and he continued to believe accordingly. In a 1965 talk to the Negro American Labor Council (often overlooked, King had strong and important relationships with the labor movement), King bluntly observed, “there must be better distribution of wealth and maybe America must move toward a democratic socialism. “ A year later he explained that solving the “economic problem of the Negro” would involve “billions of dollars.” You can’t end slums, he added, without “profit . . . be[ing] taken out of the slums. But if you do that, “you’re really tampering and getting on dangerous ground . . . You are messing with captains of Industry.” To do this would be tread “in difficult water, because it really means that we are saying that something is wrong with capitalism.”

In August, 1967 King delivered one of his more important addresses to the SCLC Convention. Titled, “Where Do We Go From Here” (and the basis of a book with the same title), he showed that his analysis had moved beyond race in the South to class and capitalism nationally:

I want to say to you as I move to my conclusion, as we talk about “Where do we go from here,” that we honestly face the fact that the Movement must address itself to the question of restructuring the whole of American society. There are forty million poor people here. And one day we must ask the question, “Why are there forty million poor people in America?” And when you begin to ask that question, you are raising questions about the economic system, about a broader distribution of wealth. When you ask that question, you begin to question the capitalistic economy. And I’m simply saying that more and more, we’ve got to begin to ask questions about the whole society. We are called upon to help the discouraged beggars in life’s market place. But one day we must come to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring. It means that questions must be raised. You see, my friends, when you deal with this, you begin to ask the question, “Who owns the oil?” You begin to ask the question, “Who owns the iron ore?” You begin to ask the question, “Why is it that people have to pay water bills in a world that is two thirds water?” These are questions that must be asked.

After the Civil and Voting Rights Acts went into effect after 1965 and the southern apartheid regime was finally being dismantled, King’s focus on inequality and the economy changed his standing in America and would become his undoing (see Poor People’s Movement below) as liberals, who’d supported him when he was seeking inclusion in the American system for Blacks in the South, now began to abandon him when he spoke of the greater problem of material injustice for Blacks and inequality for all poor people all over America. The Civil Rights campaigns sought jobs along with justice, but never challenged the structure of capitalism; rather they sought to include 15 million or so Blacks in the American economy—as investors, workers, and consumers. But King’s rejection of capitalism, along with his global notoriety as a Nobel Peace Prize winner and his popularity among the poor, made him a threat to all segments of the ruling elite, not just southern politicians and bigots.

Vietnam and State Violence. Americans, especially liberals, loved MLK as he spoke out against the violence being committed against Blacks by southern sheriffs like Bull Connor or Jim Clark, but, as he pointed out, they turned on him when he spoke out against the violence American troops were committing against the people of Vietnam. Speaking on April 4th, 1967 (note the eerie coincidence of the date), King offered a sermon titled “A Time to Break the Silence” (also referred to as “Beyond Vietnam”) in which he assumed the mantle of not only Civil Rights leader but radical critic of American militarism and imperialism.

To King, there was a “very obvious and almost facile connection” between the U.S. war in Vietnam and the struggle for civil rights and against poverty at home. With the military buildup, King watched the commitment to domestic justice and equality “broken and eviscerated as if it were some idle political plaything of a society gone mad on war.” At the same time, Vietnam was showcasing the government’s hypocrisy on racial matters as African-Americans and other minorities were dying in extraordinarily high proportions in the early years of the war though they accounted for a small percentage of the population. “We were taking the black young men who had been crippled by our society,” King charged, “and sending them eight thousand miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in southwest Georgia and East Harlem.”

Not four years earlier King dreamed of an America in which “little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls and walk together as brothers and sisters.” Violence in Vietnam, however, had brought them together, and Americans watched those black and white boys “in brutal solidarity burning down the huts of a poor village” though “they would never live together on the same block in Detroit.” As King saw it, the commitment to racial reconciliation and social improvement was dying on the battlefields of Vietnam, causing a rupture in the social fabric unlike any in the twentieth century.

As a result, Americans faced the “cruel irony” of watching those black and white American boys kill and die together in the service of a country “that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools.” Because of these circumstances, King, who had developed a strong relationship with the White House and the liberal establishment, had to speak out; he “could not be silent in the face of such cruel manipulation of the poor.” At home, as the Reverend saw it, racial division had become increasingly contentious, with urban uprisings in the North becoming as common as anti-black violence in the South had been earlier in the decade.

Abroad, especially in Vietnam, U.S. actions were marked by mayhem and destruction as well, as American soldiers, weapons, and airplanes inflicted massive levels of damage on the residents of a small agrarian society. The United States, King thus concluded, remarkably, was “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.” And he called for militant action: “These are the times for real choices and not false ones,” he lectured. “We are at the moment when our lives must be placed on the line if our nation is to survive its own folly. Every man of humane convictions must decide on the protest that best suits his convictions, but we must all protest.”

The relationship with the White House and liberals that had been instrumental in ending apartheid in the South was now frayed to the limit. King had been expected to remain silent and support LBJ’s policies, but his break with the war, in such stark terms, marked the point of no return. Southerners had long tried to discredit King as a Communist, but those charges hadn’t stuck. Now, liberals would see him as a strident radical, and he would no longer have the support of politicians, media, and much of the white establishment. MLK’s world had changed, and with it American politics.

Olympic Boycott. King’s radical analysis and actions aren’t well-known but if one studies his life, his views on the economy and Vietnam become apparent. But even among those who are familiar with the full legacy, his embrace of the 1968 Olympic Boycott—public and sturdy—comes as a surprise. In the past generation or so—since the 1992 “Dream Team” exploded the myth of amateur sports in the Olympic games—the quadrennial sporting event has remained a huge media event, but much of the national passion for the games has dissipated. In the period after World War II, however, the Olympics had immense importance as a political event, a showcase for American athletes to show not just their ability to run, swim, throw a discus, or whatever, but, more importantly, their superiority to athletes from the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. It was a very important, epic really, battleground in the Cold War. To criticize the Olympics was almost unheard of, and to simply not care about them was a cause for suspicion.

So when Black athletes, who had won so many medals in Olympic competition, in 1967 started talking about actually refusing to participate in the 1968 games scheduled for Mexico City to protest racial conditions at home, the reaction was fierce, with sportswriters and politicians in particular attacking Harry Edwards, who came up with the idea, and any Black athlete rumored to support it. The vast majority of Americans, including the vast majority of Blacks, opposed the very idea of boycotting the games. It’s hard to understand in 2016 just how controversial and radical the idea was—it could, and it did, ruin people’s careers and lives. Boycotting the Olympics, without exaggeration, was akin to burning an American flag.

And, yet, on December 15th, 1967, Martin Luther King, Floyd McKissick of CORE, and Harry Edwards held a press conference in New York to publicly support the Olympic Boycott by African American Athletes. King did not equivocate. “I absolutely support the boycott, not only as Martin Luther King, but as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference,” he made clear. King had earlier spoken with athletes like the sprinter John Carlos (who would medal in the 200 meters but be sent home along with Tommie Smith for their powerful black-gloved Black Power salute) to encourage the boycott, but the press conference was a huge step forward in his radical evolution.

The Boycott Movement had six demands, conditions to be met if Black athletes were to participate on the American Olympic team. They included an end to discrimination at the famed New York Athletic Club; the restoration of Muhammad Ali’s stripped Heavyweight title because he’d refused to be drafted; at least one more Black coach on the U.S. Olympic team; a ban on South African and Rhodesian participation in the games; and the removal of Avery Brundage, an old Nazi, as head of the International Olympic Committee (Brundage, to show he was not racist, made sure to express his opinion that 1936 Olympic hero “Jesse Owens is a fine boy”).

Ultimately, the Boycott had little effect. Among well-known athletes only Lew Alcindor (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) refused to participate, and the Smith and Carlos controversy dominated the games and gave Brundage all the reason he needed to remove them from the Olympic team and send them home (with USOC agreement of course). But the Boycott attempt did have one major success. Due to the pressure put on Brundage and others by King especially, the IOC had a re-vote on South Africa’s admission to the games and this time banned it from participating. While far from the larger outcome they sought, the Boycott leaders had a measure of success and King had shown, without doubt, that he was a global leader with radical views, and he wasn’t going to avoid expressing them publicly. (See Jet, December 26, 1967; also see David V. Gray, “A Prelude to the Protest At The 1968 Mexico City Olympics,” History M.A. Thesis, San Jose State University, 1997).

Poor People’s Campaign. King’s last crusade was, in some ways, going to be his biggest, and greatest challenge. Taking on the Jim Crow system was vast and now he was aiming at the system of class and inequality in the entire country, a nation-wide “Poor People’s Campaign.” King and SCLC had announced in late 1967 that would organize a national effort to address the lack of wealth and democracy among the poor. As King explained, “We intend to channelize the smoldering rage and frustration of Negro people into an effective militant and nonviolent movement of massive proportions. We will also look for the participation of the millions of non-Negro poor—Indians, Mexican-Americans, Puerto Ricans, Appalachians, and others. And we shall welcome assistance from all Americans of good will.”

A centerpiece of the Campaign was an “Economic and Social Bill of Rights” that King and his associates created in early 1968. It pointed out that the U.S. Bicentennial was coming up, but asked “Two hundred years after the Declaration of Independence will the right to the pursuit of happiness mock the majority of Negroes locked up in an economic underworld of poverty, joblessness, and unemployment?” Clearly his work had now shifted into a focus on the problems of American capitalism. He also again connected the the new crusade to the problem of Vietnam, pointing out that the “black and white poor” were carrying out the fighting, and dying as well, in Vietnam.

Sounding like Frederick Douglass excoriating the Fourth of July, King aimed at the Bicentennial—“will Negroes be able to celebrate?”; “what is it that the young people in the streets have a right to—a life of unemployment and low pay when there is work?” Thus his Bill of Rights demanded decent jobs for all employable people, pointing out that many ghettos had 30-50 percent under- and unemployment rates. King also demanded careers, not “make-work” jobs or quick-fix public employment programs. With that came the demand for a minimum income, noting that in 1965 almost 30 million poor people could not even receive public assistance. The right to “decent housing and free choice of neighborhood” came next, with the added observation that suburbs were being built all over with subsidized credit and public infrastructure, while blacks and poor whites were being sent to public housing and living in substandard “projects.”

The Bill of Rights ended with demands for adequate education and funding for Black and poor schools, the right to participate in the decision-making process (a clear link between the Campaign and earlier efforts like those of SDS for “participatory democracy”), and the right to national health care to stop the “scandal” of life spans depending on class and race. King was demanding no less than a serious commitment to the poor in ways that the ruling class had never attempted or allowed, along with an end to the war in Vietnam, where, he claimed, the U.S. was spending $500,000 for each enemy soldier killed compared to $53 for each poor person at home. It was, in all ways, a radical document.

As the Campaign went on, King sought out all segments of the American population living in poverty, not just southern Blacks but urban and rural, industrial and agricultural workers. This was, probably for the first time since the Populists in the 1890s, an attempt to develop a nationalclass movement against the way American capitalism was constructed and practiced. King pointed out the inequality inherent in America, where over 35 million could not afford a minimally decent, healthy life. “Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, poor whites, and Orientals who are crushed down by economic forces make incomes that fall below the ‘Poverty Line.’” Their incomes, he added, averaged about $3000/year for a family of four, only about one-third of the average budget for a family in an urban area. Jobs, wages, housing, health care, and dignity were thus “moral and constitutional” issues, as he explained things.

The Poor People’s Campaign, however, would play out much differently than the Civil Rights Movement. Liberals, who had been so supportive of his pre-1965 efforts, now turned on King as he was challenging them on their home turf, pointing out problems in the North and with the Capitalist system and making demands that would surely lead to tax increases if ever put into effect. Harry McPherson, one of LBJ’s closest aides, complained in a moment of liberal candor that “the Negro . . . showed himself to be, not only ungrateful, but sullen, full of hate and the potential for violence.”

The Poor People’s Campaign, however, would play out much differently than the Civil Rights Movement. Liberals, who had been so supportive of his pre-1965 efforts, now turned on King as he was challenging them on their home turf, pointing out problems in the North and with the Capitalist system and making demands that would surely lead to tax increases if ever put into effect. Harry McPherson, one of LBJ’s closest aides, complained in a moment of liberal candor that “the Negro . . . showed himself to be, not only ungrateful, but sullen, full of hate and the potential for violence.”

Such liberal sentiment was surely widespread and the Campaign never gained traction. The government made it difficult for King to get permits for public events in Washington D.C. and had agents keeping surveillance on key leaders. The, on April 4, 1968 in Memphis, while supporting the efforts of AFSCME to gain recognition as the union for sanitation workers, King was murdered by a barely literate drifter who escaped and was later caught in London with a forged passport . . .

The Poor People’s Campaign went to Washington but “Resurrection City,” as they named their encampment, was a muddy, often disorganized, and generally dismissed gathering, nothing like King’s vision. The movement was ineffective and easily ignored, with the majority of Americans simply tired of the protests of Blacks and the poor. Even had King remained alive, such an outcome was virtually inevitable. Taking on race in the South was a vast task, but it was consistent with the interests of many Americans who understood that Blacks could be consumers and the apartheid system was a global scandal. And it was a movement for inclusion that was not anti-capitalist in any way. The Poor People’s Campaign was King’s recognition that fundamental problems of class and poverty were not eradicated and a bigger crusade, with capitalism in its sights, was needed. And that was his ultimate undoing.

In one of his last letters, in April 1968, King sent out an appeal for support of the Campaign and included the line, underlined for emphasis, that “We cannot condone either violence or the equivalent evil of passivity.” While his commitment to nonviolence is widely-known, and is the hallmark of his national holiday, his commitment to resistance, to strong resistance, is overlooked generally. King was fond of quoting Dante’s admonition that the lowest circle of Hell was reserved for those who remained neutral in a time of moral crisis.

King’s approach stressed nonviolence but it was “militant” nonviolence, direct resistance at the point of action against the “evil” of not acting. Some of his peers and rivals—like Malcolm X and some Black Panthers—derided him angrily, even calling him an Uncle Tom. But King’s approach and his analysis, especially as it evolved, was indeed militant as it increasingly challenged the state and economic elite not just to get rid of apartheid but to take on the inevitable consequences of capitalism—inequality, poverty, housing, health care—and that made him a threat to the very people who had supported him just years earlier. He might have seemed “ungrateful” and “sullen” to many liberals, but he was carrying out a mission that was rare in American history—an anti-capitalist crusade that would bring people together across lines of race, ethnicity, and gender.

In his anti-Vietnam talk in 1967, King said “I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin…we must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.” This weekend, as we “celebrate the dream,” those ideas and words will not be heard on a TV commercial, in a typical school room, or in an “official” testimonial. We will instead hear, legitimately, about his dream in August 1963 and how we, as a country, overcame our past and brought racial justice to America. Indeed, we now have an African American president, evidence, to many, that the evils of the apartheid era are long behind us, Black unemployment, cop killings, record corporate profits, and drone wars notwithstanding.

But King’s legacy, while being honored, has been, to a real degree, changed, even sanitized. Few Americans are aware of his admonition of America as the “greatest purveyor” of global violence, or his embrace of socialism, or his attacks on poverty and inequality across racial lines. Indeed, to hear about the reality of King, and his legacy, one would find it in a few places, like the Black Agenda Report, or among intellectuals like Adolph Reed or Cornel West, or on the animated show “Boondocks,” but it’s not easy to discover, and it’s not a marketable commodity. In order to “sell” King as a national hero, worthy of a national holiday, we have to ignore a good deal about him. America’s national holidays honor individuals who became known through genocide and wars—Columbus, Washington, Lincoln. King’s day is unique, a commemoration of a man of peace who challenged the state and elite on many different levels. To make his full story part of that celebration would be more than an aberration, but a danger to certain interests.

We don’t need “a” Martin Luther King—campaigns and movements rely on masses of people, not necessarily a great individual. But once King was put on that pedestal, it became imperative to create a “safe” version of him and to make sure those who are comparable to King today (the Rollo Goodlove types who show up in Ferguson, Baltimore and other places where there are TV cameras) aren’t trying to organize the masses. Aaron McGruder of “Boondocks” created a controversial episode speculating that King had remained in a coma for decades after he was shot and regained consciousness in the early 2000s, where he was a critic of the war on terror andbecame a reviled national enemy. It was consistent with King’s actions, but this part of his thinking isn’t so widely known; indeed, it  is in the interests of those who control the past to keep such realities under wraps. Ultimately, it speaks volumes that a cartoon on cable television provides us with a historical lesson much different, and much closer to reality, than the one our leaders are selling to us in mid-January every year.

is in the interests of those who control the past to keep such realities under wraps. Ultimately, it speaks volumes that a cartoon on cable television provides us with a historical lesson much different, and much closer to reality, than the one our leaders are selling to us in mid-January every year.