Above Photo: A West Papuan activist in traditional costume protests in Jakarta for Papuan self-determination. EPA Images

Almost every December, the Indonesian region of Papua makes headlines both nationally and further afield. In 2018, following the arrest of hundreds of Papuans commemorating the region’s “independence day” on December 1, the nation was shocked by the killing of 31 construction workers allegedly by armed separatists – although the details are still unclear. There are now fears the violence could escalate.

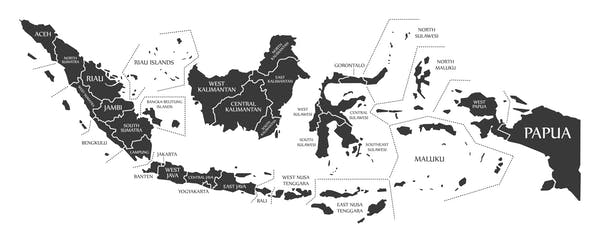

Ironically, these events took place as the Indonesian government makes a tremendous effort to develop Papua – which makes up the western half of the island of New Guinea and includes the Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Papua. In fact, no other Indonesian region outside Java receives so much attention, with the nation’s president, Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, visiting two or three times annually in recent years.

But while his attention has been appreciated, Jokowi has also been accused of having a poor attitude to human rights abuses and state violence in the region. And while the president enjoys wide public support in Papua, the aspiration of Papuan self-determination is gaining traction both domestically and internationally.

The Jokowi Way

Since Papua was granted special autonomy (or “Otsus”) status by Indonesia in 2001, Jokowi’s prosperity-based approach has focused on developing infrastructure and improving connectivity. The government’s 4,330km Trans-Papua road project, for example, aims to put an end to the isolation of many Papuan communities.

Jokowi also introduced the “BBM Satu Harga”, a national standard price for fuel. This policy aims to bring down the cost of fuel in Papua, which can reach Rp50,000-100,000 (£2.70-£5.40) per litre, nearly ten times the average price nationally. The pricing policy has proved popular, although in practice Papuans in the region’s highlands only enjoy the standard national price once or twice a month due to supply constraints.

During Jokowi’s presidency, central government funding has also increased for both Papuan provinces. In 2016 alone, the central government allocated a 85.7 trillion rupiah (£4.6 billion) development fund for Papua and West Papua. On top of this Otsus fund, both provinces also have benefited from additional infrastructure spending.

But while Papua has received a larger share of the country’s development fund than any other region, its public service provision is among the worst in the country. Major public health disasters are commonplace, such as the recent measles outbreak in Asmat Regency, which along with malnutrition killed hundreds of children. In fact, Papua has been at the bottom of the national human development index for decades.

Jokowi has also focused on developing security, deploying thousands of additional soldiers to the region. Although aimed at strengthening national defence, there are ongoing concerns about human rights abuses in the region. A recent report by Amnesty International indicates that extrajudicial killings involving security personnel are still taking place in Papua.

Jokowi has also been criticised for failing to deal with such abuses when they occur. So far, none of the human rights cases relating to Papua have been resolved during his administration, leading to growing Papuan distrust of Jakarta (Indonesia’s capital and the seat of the national government). According to one Papuan leader I interviewed:

Jakarta is busy chasing away the smoke but not trying to put out the fire.

Self-determination

Against this backdrop, the campaign for Papuan self-determination is growing. While there is some armed resistance, most Papuans campaign peacefully through democratic action such as mass rallies and social media campaigns. Domestically, this peaceful campaign is directed by the National Committee of West Papua (KNPB), the Papuan Student Alliance (AMP), and The Democratic People’s Movement of Papua (Garda Papua). These organisations are mostly supported by Papuan youths and students.

But they have also been active beyond Papua, including in many of Indonesia’s biggest cities, such as Yogyakarta, Jakarta, Bandung and Surabaya on the island of Java, Denpasar on Bali, Medan on Sumatra, and Makassar and Manado on Sulawesi. Recently, the cause also received support from non-Papuan groups, such as the Jakarta-based Indonesian People’s Front for West Papua (FRI WP).

Nor is this just a domestic issue. The United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP) was established in December 2014, two months after Jokowi took office, and has since been building support for the cause among Pacific nations. Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands and Tuvalu have raised the Papuan issue in UN forums many times.

Which all goes to show that the Indonesian government’s strategy in the region has been less fruitful than expected.

Time to reflect

Jakarta’s trust-building project in Papua is falling short because of the government’s narrow perspective of the problem. Since the late 1990s, all Indonesian presidents except Gus Dur have tended to make the Papuan issue all about economic development. Other crucial issues stated in the “Otsus Law”, such as Papuan identity, local political parties, law enforcement, human rights and the protection of indigenous people, have been overlooked.

Consequently, rather than facilitating the emergence of a strong and autonomous Papuan government, Otsus has made Papua even more dependent on Jakarta. And as the human rights issues remain unaddressed, the slogans of self-determination are being shouted even louder.

Jakarta and Papua must now come together and reconsider the best options for a more constructive future relationship. For if the 17 years since the region was granted Otsus status have revealed anything, it’s that economic development alone is not enough to win the hearts and minds of the Papuan people.