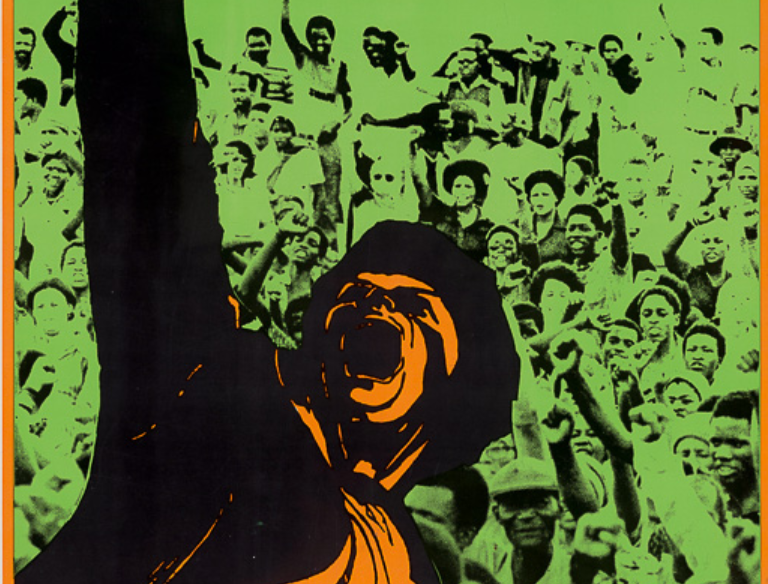

Above photo: Alberto Blanco González (OSPAAAL), Namibia: Power to the People, 1981. Courtesy of The Radical Media Archive.

Sixty years after the Tricontinental Conference, the right to development – the material basis of dignity – remains the horizon of socialist revolution and national liberation.

In memory of Mehdi Ben Barka (1920–1965), in whose footsteps we walk.

Nearly sixty years ago, in January 1966, hundreds of revolutionaries from across the Third World gathered in Havana, Cuba, for the First Solidarity Conference of the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America – the Tricontinental Conference. There, they discussed the inevitability of decolonisation and their ideas for a world beyond imperialism. Fidel Castro and the other organisers called the conference to bring together the two currents of world revolution: the current of socialist revolution and that of national liberation. The delegates saw the need to radicalise the ideals of sovereignty that had been given voice ten years earlier at the Bandung Conference. They were frustrated that the world order remained trapped in the structures of neocolonialism that kept even newly independent countries in cycles of underdevelopment, with formerly revolutionary national liberation parties demobilising as soon as new flags went up and new anthems began to play.

To commemorate the legacy of the Tricontinental Conference, which gives our institute its name, this month we released dossier no. 95 Imperialism Will Inevitably Be Defeated: The Re-Emergence of the Tricontinental Spirit (December 2025). Throughout 2026 we will also organise several online and in-person discussions and seminars (the first of these, co-hosted with CLACSO, the Latin American Council of Social Sciences, can be viewed here). In the dossier we argue that while the Bandung Spirit was anchored in an insistence on sovereignty and multilateralism, the Tricontinental Spirit pushes further, grounding true emancipation in dignity and the class struggle.

One of the key ideas of the Bandung and Tricontinental eras was that dignity cannot be achieved without development – and that the right to development belongs to all peoples in the world. In November 1957, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) adopted Resolution 1161 (XII) on Balanced and Integrated Economic and Social Development. Four years later in 1961, the UNGA declared that the 1960s would be the ‘United Nations Development Decade’. In May 1968, toward the end of that decade, the delegates at the United Nations International Conference on Human Rights in Tehran, Iran, adopted The Proclamation of Tehran, which warned:

The widening gap between the economically developed and developing countries impedes the realisation of human rights in the international community. The failure of the Development Decade to reach its modest objectives makes it all the more imperative for every nation, according to its capacities, to make the maximum possible effort to close this gap.

The Tricontinental Conference took place in the middle of this so-called development decade. At the time, there was already a clear recognition among the leading countries of the Third World that the UN’s development framework could not close the gap so long as the global economy remained organised along structures of dependency. It would take almost two decades after Tehran for the UN to adopt a declaration on the right to development. On 4 December 1986, as many Third World states were already collapsing under the weight of a debt crisis that would stretch into the 1990s, the UNGA finally adopted the Declaration on the Right to Development. The document shone with the very best of ideals:

The right to development is an inalienable human right by virtue of which every human person and all peoples are entitled to participate in, contribute to, and enjoy economic, social, cultural and political development, in which all human rights and fundamental freedoms can be fully realised (Article 1.1).

…

States should undertake, at the national level, all necessary measures for the realisation of the right to development and shall ensure, inter alia, equality of opportunity for all in their access to basic resources, education, health services, food, housing, employment and the fair distribution of income. Effective measures should be undertaken to ensure that women have an active role in the development process. Appropriate economic and social reforms should be carried out with a view to eradicating all social injustices (Article 8.1).

States should encourage popular participation in all spheres as an important factor in development and in the full realisation of all human rights (Article 8.2).

These ideals are enshrined in UN resolutions and declarations not because of the altruism of the Global North but because hundreds of millions of people in anti-colonial and socialist movements fought for them.

Two years after the declaration was adopted, the World Bank published the World Development Report (1988), which found that the Third World’s total external debt had reached over $1.035 trillion in 1986, a staggering leap from $560 billion in 1982 and $130 billion in 1974. The report noted: ‘Their [the Third World states] debts are growing, but they still face negative net resource transfers because debt service obligations exceed the limited amounts of new financing. In some developing countries the severity of this prolonged economic slump already surpasses that of the Great Depression in the industrial countries, and in many countries, poverty is on the rise’. The International Monetary Fund reached a similar conclusion in its own assessment, which placed Third World total debt at $916 billion, a slightly lower number that still pointed to the same trend.

Next year will be the fortieth anniversary of the UN Declaration on the Right to Development, but few people will commemorate it. Since 1986, there have been efforts within the UN human rights system to move from a non-binding largely symbolic declaration towards a legally binding instrument. Yet those efforts have met sustained resistance from the wealthier nations, who see such an instrument as being detrimental to their monopoly over wealth and resources.

In October 2021, for instance, the Human Rights Council adopted its annual resolution on the right to development by a vote of 29 to 13, with 5 abstentions. The 13 votes against all came from Global North countries. Two years later, in October 2023, when the council voted to submit a draft convention on the right to development to the UNGA, the resolution again passed by a vote of 29 to 13, with 5 abstentions. All votes against once again came from the Global North countries. It is patently clear that despite the North’s rhetorical support for development, it has spent plenty of energy cutting UN resolutions on development down to size and even preventing any discussion of major debt relief, a crucial step for Global South development.

This is the contradiction at the heart of the right to development: proclaimed as inalienable yet denied in practice. Dossier no. 95 returns to the Tricontinental Spirit’s insistence that emancipation cannot be measured by flags and speeches, but by whether people’s lives materially improve. Development is not a slogan, nor a set of targets to be managed from above. It is the right to expand people’s capacity to live with dignity. But such a right will remain out of reach for most of humanity so long as debt service, coercive economic measures, and wars continue to drain the social wealth of the poorer nations. The development aspirations of the Global South will not be achieved in the halls of the UN; they will only be made real through organised struggle that compels institutions and states to act.

As the year comes to an end, so does the first decade of our existence as a research institute. We began with the ambition of being the inter-movement think tank of the Global South, our feet rooted in the more than two hundred workers’ and peasants’ organisations and political movements that make up the International Peoples’ Assembly network. Over the course of the past decade, we realised that we had two key tasks: first, to amplify the views of the movements and to stimulate a debate among them and within society; second, to build a New Development Theory for when our movements come to power and have the obligation to reshape society and lead us to a better future beyond the fetters of capitalism. As our mandate grew so did the scope of our work.

For that reason, and because you believe in our mission, we hope that you will decide to support our work for another year. We depend on your solidarity to sustain it. There are many ways to contribute:

- If you would like to join our Tricontinental Intern Brigade, please write to intern@thetricontinental.org.

- If you would like to help us with editing and translation work, please write to volunteers@thetricontinental.org.

- If you would like to make a financial contribution, please write to donations@thetricontinental.org. We truly rely on your support to continue this work.

We hope you will join our Tricontinental community.