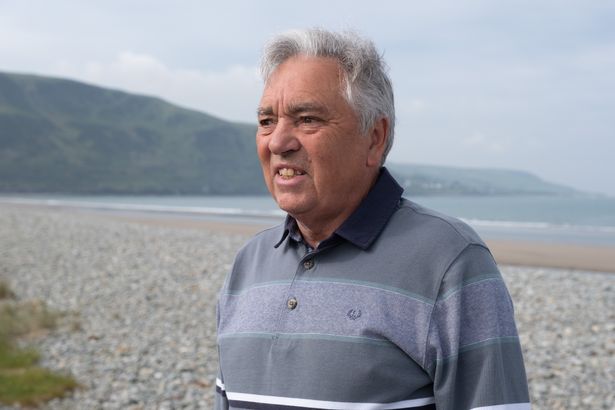

Above Photo: The village of Fairbourne on the west coast of Wales: threatened by climate change and rising sea levels, those who live there may be forced to move out (Image: Keith Morris)

The council says it can’t protect the village from the elements forever and, sooner than later, everything must go

“I’m not going anywhere. I’ll be sat in a deckchair in my back garden with the water up to my neck before I move out.”

What will your village, town or city look like in half a century? Most of us would probably imagine a more modern, populated and eco-friendly version of the environment we live in today.

But for one Welsh village the question is salient and immediate. And they have no idea what the answer is. But there’s a chance it won’t exist at all.

Fairbourne is a beautiful village. It sits on the coast of Barmouth Bay and its flat terrain is dominated by the backdrop of Snowdonia. But when you drive into the village from the north, the scale of its mountainous surroundings is not even visible through the mist.

In the face of tranquillity, there is a frenzy of activity ‘by the shops’. People are out and about. They’re talking, and they’re talking about one thing.

In 2013 Gwynedd Council decided that it could not defend Fairbourne from the elements in the long-term. It currently does, along with Natural Resources Wales, who have spent more than £6m on a flood risk management scheme in the area in the past four years.

However, a Shoreline Management Plan for the west of Wales, first commissioned by the Cardigan Bay Coastal Group in 2009, “raises significant concerns over the future sustainability of the defence of Fairbourne”.

The concerns are based on climate change and the speed at which it takes hold. Sea levels continue to rise. It’s estimated that current levels are more than 100 metres higher than during the last ice age, and that they could rise by a further two metres over the next century.

In short, there will be no money spent on defending this community of around 400 homes and 850 people after 2054. The harsh and unforgiving word ‘decommission’ has been banded about – the death of a community facilitated by its inhabitants being forced to move out, its shops closed down, its houses demolished to make way for salt marsh.

Gwynedd Council says it has not decided to ‘decommission’ Fairbourne, but they have also not ruled it out, admitting that such a step would “need to be considered”. What they have confirmed, however, is that relocating residents is a certainty.

Some people won’t be here to see it, while others are still hoping to be living and working here when the ‘masterplan’ – as it’s been called – kicks into action.

“It’s frustrating,” says Lauren Baynes, a 22-year-old who runs the village butcher’s with her partner.

“We have two young children. It would be nice to hand the business down to them one day and for the whole family to stay here – I’ve lived in the area my whole life and I’ve never known Fairbourne to flood badly.

“We’ve been open now and for three years and I want to stay here, long-term.”

The ambiguity surrounding how and when drastic action is taken to save the people of Fairbourne from the sea is what alarms most of its residents. Estimates predict that the point of no return could be as early 2042, or earlier.

“I’ve never been spoken to about any of this,” says Lauren, whose butcher shop is a stone’s throw away from the sea wall.

“Nobody has said anything about what’s going to happen, or when, or how. There’s been no word on compensation or where we would all move to.”

The word compensation continues to rear its head, no matter who I speak to.

Can residents who privately own property and land just be expected to pack their bags, move out and find another place to live in a different part of the world, on the strength of what is ultimately a forecast, without being paid for the upheaval, the distress and the heartache of leaving their lives behind?

Currently, there are no measures in place for homeowners to receive compensation when they are made to relocate.

“Most people are seriously angry at how it’s been handled,” says Stuart Eves, chair of the local community council, who has lived in Fairbourne for 43 years.

“They’ve basically said ‘we’re going to come in and take this all down’. How can they say that based on supposition? Of course we realise that sea levels are rising, but at what rate? We know there’s going to be a problem, but what we don’t know is when.”

Nobody here is denying climate change. The difficulty is knowing when it will cause Fairbourne to succumb – 2042, 2092, a thousand years from now?

What is without doubt, however, is that climate change has already had an effect on the village because, I’m told, it has driven the council and the other bodies behind the Shoreline Management Plan into a decision which will “destroy it”.

“It’s destroyed the livelihood of the village,” adds Stuart. “You can’t get a mortgage here anymore. There’s lots of young people here who want to stay and buy houses, but they can’t. Banks won’t give them the money.

“But we’re a very resilient community. The county council tried to shut the public toilets recently and we managed to form a group that took them over.

“We run them now with the help of donations from the community, and they’re some of the best public toilets you’ll see. We don’t take things lying down here.

“Climate change is real and it’s affecting the whole world, but there are many other places that will go before Fairbourne. There are places along the same coastline that have flooded in recent years; some have been under a foot of water and we have barely flooded at all.

“I appreciate that the council have been put in a difficult position. If they didn’t’ do this and something terrible happened, the finger would be pointed at them. Now they are going ahead with it, if nothing terrible happens then the finger will still be pointed at them.

“It’s the way it’s been handled that’s the issue. This village is unique, it has an aura about it, an ambience. People come here and they fall in love with the place, but house prices have already fallen here because of this ‘masterplan’.

“We don’t know what things will be like in the future. But if the council turn to us one day and say ‘right, on this date you have to move out’ then they’re going to have one hell of a fight on their hands.”

Councillor Catrin Wager, cabinet member at Gwynedd Council , says it is the “priority” of the authority to work with local people to “protect the social and economic viability of the village for as long as possible whilst also offering emotional and practical support to local people to deal with the situation the village will eventually face.”

One resident disagrees and says that, regardless of what may happen in 20 or so years’ time, Fairbourne has already been washed out.

“We feel the county council has abandoned us,” says Alan Wilde, a resident of 35 years.

“First, they closed the toilets. They also took away the concrete ramp down to the beach two years ago so there’s no safe access to our beach. The notice boards, which are essential to any holiday village, have been taken away and there’s no sign of them being replaced.

“They’re killing tourism and we feel abandoned. We’re totally in the dark.”

Hugh Harrison lives in a neighbouring street and makes an important point.

“If this village does flood then of course we will need help and support. But at the moment it’s not happening and doesn’t look like happening. Most people I speak to all say the same thing – ‘if I want to live here then it’s up to me’.”

Gwynedd Council say that discussions are ongoing to determine the best and safest way of executing their plan to relocate residents before 2054, when they say “sea level rises and changing weather patterns will mean that it will not be possible to further bolster the village’s sea defences”, a point when “the risk to residents will significantly increase”.

It says a “multi-agency project” has been established to address the complex issues that will eventually face Fairbourne.

“It is important to stress that Gwynedd Council has not decided to ‘decommission’ Fairbourne,” a spokesman said.

“Whilst decommissioning has been suggested, no firm decision has been made, and such a step will be a matter that will need to be considered by Natural Resources Wales, Welsh Government, Snowdonia National Park and the community itself.”

Councillor Wager added: “Climate change is happening, and it is unfortunately only a matter of time before it has a very real human impact on coastal communities like Fairbourne.

“By talking to the community sooner rather than later, our aim is to work through these difficult issues together in order to give ourselves as much time as possible to come up with viable options and the best possible solutions.

“Currently there is no legislative precedent or national funding stream for the so called ‘decommissioning’ of a whole community and as a council we are seeking assurances from the Welsh Government that these two issues will be addressed as soon as possible.”

Roger and Christine Kingshott, originally from Derby, recently moved to Fairbourne. They are both in their 70s and love their new home, a footpath away from the sea wall. They don’t regret moving to the village, but know people who do.

“Someone I know who’s bought a property here has said it was a mistake, because she’s worried about her children’s inheritance,” says Christine.

“We intend to carry on enjoying it as we love it here. We can’t sell now anyway with all this going on so we might as well enjoy it.

“It’s our life and we don’t want to go anywhere. It’s an absolutely wonderful place.”

Her husband Roger agrees, but says the issue has cast a cloud on what should have been a care-free existence in retirement, a period of life spent creating a legacy for their children and grandchildren to enjoy after they’re gone.

“Last winter was extremely wet but this street didn’t flood. This house was built in the 1960s and it’s never flooded,” says Roger.

“Everyone’s concerned. Nobody’s told us when or how this plan will happen, all we’ve heard is that there will be no compensation, and the issue is driving prices down. Nobody’s burying their heads in the sand, thinking that it’s too far away in the future – people are aware and they’re incensed.”

What Roger, Christine and the whole community wants, ultimately, is answers. A meeting has been called for June 26 at the village hall, where it is hoped the ‘masterplan’ outlining Fairbourne’s future, or lack of it, will be laid bare to all.

Throwing money at coastal defences is no longer an option in Wales

For hundreds of years, many towns and cities around the Welsh coastline have tried to defend themselves against the natural forces of the sea.

That’s why you will see solid sea walls at Penarth, the long wooden groynes on Saundersfoot beach and tall piles of pebbles at Amroth and Newgale in Pembrokeshire.

It’s why the Romans built the 35km-long sea wall and sea defences which run along the Gwent Levels coast line. The Wentlooge Levels are around seven metres above sea level, but the Severn Estuary has the second highest tidal range in the world, at 15m. If it wasn’t for the wall, most of the Levels would be submerged under several metres of water twice a day.

Coastal defences are designed to hold the shoreline, keep beaches in place and stop the waves and tides from flooding properties.

This approach has served us fairly well over time, but now this is under threat thanks to the effect of climate change.

No one really knows exactly what is going to happen as the earth’s atmosphere warms up and sea levels increase. But it is pretty well accepted by now that for those communities living on the coast, protecting their homes and livelihoods will almost certainly get tougher.

Throwing more money at the problem and building our defences higher and stronger just isn’t an option any more.

Since 1990, the mean sea level around the globe has risen by around 20cm. The latest estimates by DEFRA indicate that between now and 2025 they will rise a further 2cm. By 2050, they are set to rise by more than 25cm. And in 100 years, we should expect to see sea levels some 1.05m higher than they are today.

It’s a scary thought, especially for villages like Fairbourne where much of the land is already below the level of normal high tide.

Paul Blackman, director for flood risk consultancy Wallingford HydroSolutions, said current sea level rise predictions would “cause increased over-topping of existing flood defences”.

He said: “There is a limit as to how high defences could practically be raised. The relocation of communities is a very traumatic solution, but may require consideration in the most extreme cases.”

Detailed shoreline management plans will dictate exactly how sea level rise and coastal flooding will be managed around the Welsh coastline over the next 100 years, and whether defences can continue to be maintained, or if they should be changed or even left alone in future.

The plans show there are 48 areas around the Welsh coastline where some homes may be at risk as a result of the policy decided on.

Here is a list of some of those areas most at risk:

Swanbridge, Sully

Existing defences will be maintained in the short term then allowed to fail. This is likely to result in the loss of residential and non-residential properties along the coast.

Newton, Porthcawl

Although the defences would be maintained for as long as possible, they will be allowed to fail. This would result in increased flood and erosion risk and potential loss of frontal properties.

Oxwich Bay, Gower

Properties adjacent to the shore are at risk from coastal erosion and flooding. It is unlikely that new defences would be constructed and therefore there will be an increased risk of coastal erosion and flooding to these properties.

Port Eynon Bay, Gower

Properties adjacent to the shore are at risk from coastal erosion and flooding. It is unlikely that new defences would be constructed and therefore there will be an increased risk of coastal erosion and flooding to these properties.

Laugharne

There remains a risk of coastal flooding (and erosion) to Laugharne village since a surge barrier was not constructed, as the local community were primarily concerned with the associated aesthetic impact on the village.

Pendine, Carmarthenshire

In the long term, the aim is to undertake a managed realignment scheme at Pendine. As a result of this, some seafront properties are likely to be lost.

Amroth, Pembrokeshire

Once the existing defences fail the shoreline will be allowed to naturally evolve and retreat which will result in the loss of frontal properties.

The village used to have a second row of terraced homes on the beach side of the road, but these were completely destroyed after severe winter storms in the 1890s and 1930s. Major erosion along the shore swept away homes, workshops, gardens, garages and boathouses which are now but a memory in old photographs.

Wiseman’s Bridge, Pembrokeshire

Properties are likely to be lost due to coastal erosion at Wiseman’s Bridge where defences will be maintained in the short term, before being allowed to fail.

Saundersfoot

Flood and coastal erosion risk will continue to increase over time. This policy is subject to a further detailed study to investigate the future risk, but options for adaptation measures include protection measures or relocation of properties.

Newgale sands, Pembrokeshire

Along with the road, increased flooding to the valley is likely to make the properties and businesses untenable after 50 years or so.

New Quay bay

Expected that some properties together would be lost within the next 10 to 30 years.

Borth

There is the need in the future to adapt use of the lower village and the very probable need to relocate people in the future as sea level rises.

Fairbourne

Plans involve the relocation of property owners and businesses from Fairbourne

Fegla, near Fairbourne

Possibility for local defence but recognised to be major changes in expectation for continued defence and significant resource would be needed to manage this change.

Mawddach Estuary

It is not considered realistic to commit to the increasing cost of maintaining and raising defences upstream of Penmaenpool. Consideration might be given to local defence of specific property.

Barmouth

This is likely to require some future realignment of the defences, quite probably with the loss of property.

Hirael, Bangor

It is not considered sustainable to maintain the shoreline defence over the period of the SMP. To take this approach would require developing a plan for moving people and businesses from the area.