Above Photo: People visit a makeshift memorial at the scene of a mass shooting in El Paso. AP PHOTO/JOHN LOCHER

The El Paso shooter wasn’t a “lone wolf.” His act of white supremacist terror is part of a century of racial violence targeting fronterizo communities.

In the immediate aftermath of the El Paso shooting—the largest massacre of Latinx people in the history of the United States—politicians of all stripes stood before the cameras and gave their diagnosis of what just happened. They sounded like the proverbial blind men who touched one part of the elephant and confused the different fragments for the whole. El Paso Mayor Dee Margo, a Republican who once praised the “freedom fence” for keeping out “riff raff,” emphasized that the atrocity was committed by an outsider. Other voices blamed mental health, video games, and the lack of gun control laws.

But none of these diagnoses went deep enough, looking only at the symptoms. Before we know how to fight back effectively against white supremacist terrorism like the El Paso massacre, we have to know exactly what we’re up against. History offers an important instrument to determine the root causes of what I characterize as a deadly epidemic.

The chilling manifesto reportedly posted online by the alleged shooter tapped into entrenched narratives with deep roots in the history of the U.S.-Mexico border. It’s unlikely that the 21-year-old from Allen, Texas, knew just how utterly repetitive his words and actions were.

The shooter wrote that he was protecting whites in America from “cultural and ethnic replacement” brought on by “the Hispanic invasion of Texas.” He claimed that “Hispanics will take control of the local and state government of my beloved Texas, changing policy to better suit their needs.”

According to one witness, as the perpetrator gunned down people in each aisle, he allowed anyone who “didn’t look Mexican” to walk away unharmed. Individuals with brown skin had no such pass. It didn’t matter to the alleged killer whether his targeted victims had legal papers or on what side of the barbed-wire fence they were born. He couldn’t have cared less whether the eight Mexican nationals among the 22 people he murdered had permits to shop in the United States.

The manifesto explains why distinctions of legal status were irrelevant to him: “Even though new migrants do the dirty work, their kids typically don’t. They want to live the American Dream which is why they get college degrees and fill higher-paying skilled positions.” In other words, brown people with college degrees threaten the racial purity of white America.

I am a third-generation native of El Paso. One of the Mexican Americans killed by the assassin’s bullet was Art Benavides, a friend of mine from high school, a happy-go-lucky guy who served for 23 years in the U.S. Army and Texas National Guard. He and I had been co-captains of the Jefferson High School swim team. El Paso, population 700,000, has been described as one of the largest small towns in the United States. Here, everyone seems to be connected by only one or two degrees of separation, and a tragedy such as this one is very personal.

The El Paso shooter’s manifesto is fully immersed in alt-right writings of individuals and groups who claim to be fighting against the “Great Replacement,” as one of their leaders calls the purported threat of “white genocide” around the world. Followers of this conspiracy theory aim to create a neo-fascist “ethnostate” where at least 90 percent of inhabitants are white. Their proposed program will be carried out by draconian border enforcement measures that will deter future migration, mass deportations, the revocation of birthright citizenship, and the purging of nonwhite children (who represent the greatest threat to the disappearance of the white race). According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, massacres like the one in El Paso are part of a strategy these extremist groups call “accelerationism,” the idea that the deliberate spread of terror is necessary for the elimination of nonwhites from this country.

But historians know that these proposed measures for the racial purification of the nation, enforced by violence, are by no means new.

In the early 20th century, the American eugenics movement called for the exclusion and elimination of nonwhites, undesirable “aliens,” and those deemed genetically inferior from the United States through draconian immigration restrictions, incarceration, urban removal, miscegenation laws, and scientific baby contests. More than 60,000 people were forcibly sterilized in government-run programs. These calls for the creation of a genetically superior race were by no means part of a fringe movement. They were prevalent among the nation’s elite.

One of the most influential American racial hygienists was Madison Grant, author of the 1916 book Passing of the Great Race. He wrote: “The Mexican Indian has no racial qualities to contribute to the United States population that are now needed.” He recommended that Mexicans “should be deported as fast as they can be located and funds made available” despite the likelihood that “a storm of protest will arise from the radicals and half-breeds claiming to be Americans, who will all rush to the defense of their kind.”

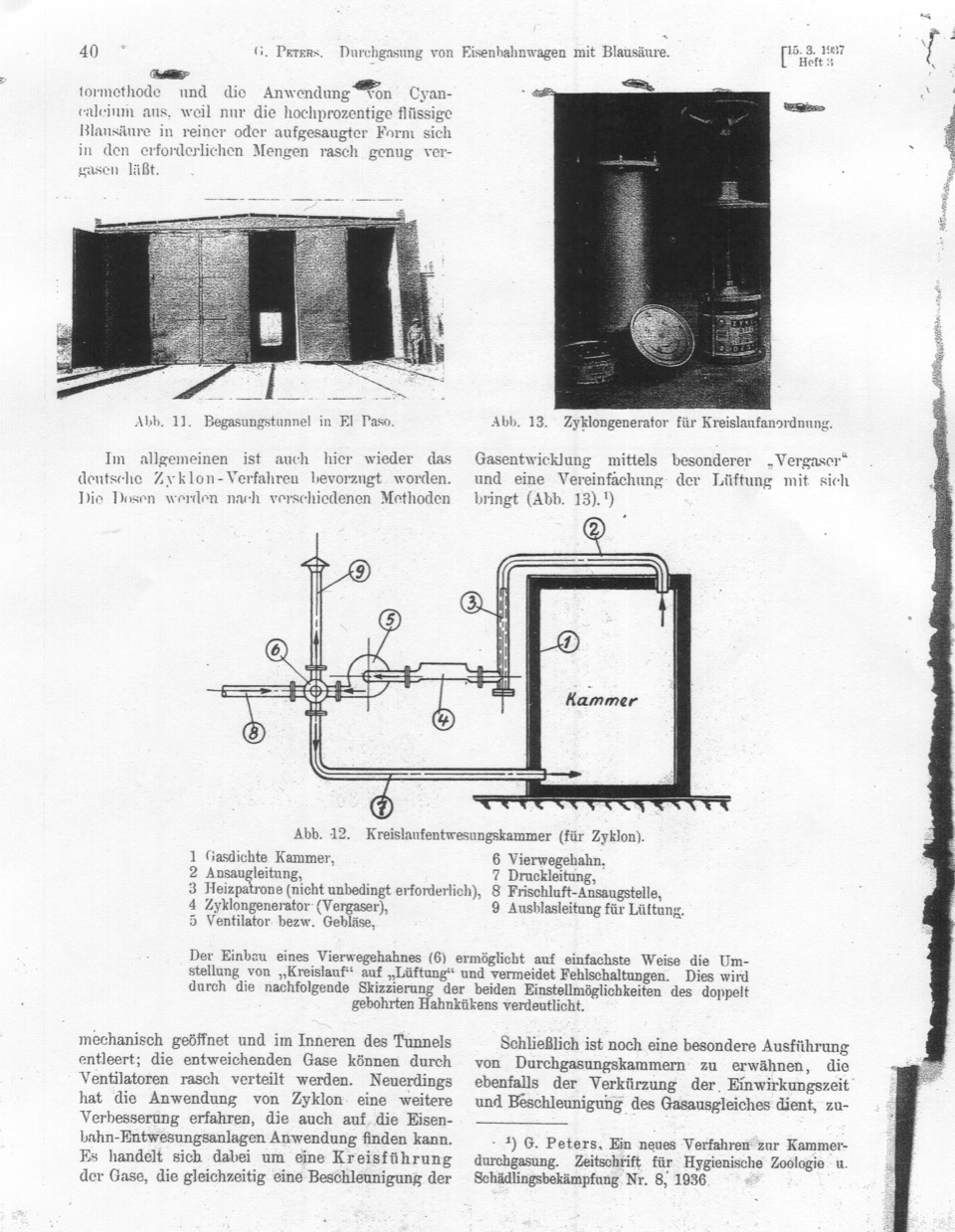

Along the U.S.-Mexico border, these proposals to exclude people deemed genetically unfit left a long and pernicious legacy. In 1917, U.S. public health officials began disinfecting all Mexican border crossers at the Santa Fe International Bridge at the El Paso-Juárez border with highly noxious pesticides including kerosene, and during the next decades, DDT and Zyklon B.

In 1937, the use of Zyklon B, or hydrogen cyanide, as a fumigation agent on the southern border inspired Dr. Gerhard Peters to call for its use in Nazi Germany. Peters wrote an article for a German pest science journal, Anzeiger für Schädlinskunde, which included two photographs of El Paso delousing chambers. He used the El Paso example to demonstrate how effective Zyklon B was as an agent for killing unwanted pests. Peters became the managing director of Degesch, one of two German firms which acquired the patent to mass-produce Zyklon B in 1940. During World War II, the Germans would use Zyklon B in concentrated doses in the gas chamber to exterminate millions of people the Nazis considered subhuman “pests.”

Nazi eugenicists paid close attention to other American practices as well. One of them was the forced sterilization laws in California that were applied against an estimated 20,000 women of Mexican and Native American descent and other ethnic minorities between 1920 and 1964. These served as models for Germany’s forced sterilization law, which went into effect January 1, 1934.

In the U.S., the Immigration Act of 1924 — which established the Border Patrol — was another piece of legislation based on the principles of racial purity and white supremacy. Hitler praised this law enthusiastically, stating, “Compared to old Europe, which had lost an infinite amount of its best blood through war and emigration, the American nation appears as a young and racially select people. The American union itself, motivated by the theories of its own racial researchers, has established specific criteria for immigration … making an immigrant’s ability to set foot on American soil dependent on specific racial requirements.”

Eugenics weren’t the only way that Anglos exerted control over fronterizocommunities. Around the same time, vigilante lynch mobs and extrajudicial murders by the Texas Rangers took hundreds of lives. Scholars have identified at least 600 lynchings in the United States of persons of Mexican descent by white mobs between 1848 and 1928. But these numbers do not include the murder of ethnic Mexicans by the Texas Rangers. The 1918 massacre at Porvernir, where Texas Rangers marched 15 boys and men out of town and shot them in cold blood, was one of many acts of state-sanctioned terrorism against people of Mexican origin along the Rio Grande Valley during the early 20th century. As Benjamin Johnson writes in Revolution in Texas: “Even observers hesitant to acknowledge Anglo brutality recognize that the death toll was at least three hundred. Some of those who found human remains with skulls marked by execution-type bullet holes in the years to come were sure that the toll had been much, much higher, perhaps five thousand.”

Low-intensity warfare against people of Mexican descent has been going on for a long time on the border. Some of the current policies by the Trump administration echo the practices at the border a century ago. For instance, just last week U.S. customs agents began to publicly inspect the heads and bodies of border crossers for lice at the Santa Fe International Bridge.

But not everything is repetition. What is new is the staggering acceleration of events currently aimed at fronterizo communities. El Paso has now become ground zero for a Blitzkrieg, a lighting-speed war waged by the Trump government against fronterizos. It seems every week, sometimes every day, we are bombarded with new twists and turns to the ruthless measures aimed to prevent “the browning of America”: detention camps for children, mass deportations, threats to revoke birthright citizenship, calls for “sending back” American citizens of color who speak out against Trump’s policies, threats to shut down all traffic at the border as a form of political blackmail. Some of these strategies are reminiscent of psychological warfare operations that are meant to keep besieged communities feeling confused, fearful, overwhelmed, and in a constant state of shock. Things are moving so fast it’s hard for fronterizo populations to know how to respond.

Historians now face a new challenge. We must not only understand the past, but what the past can teach us about how to alter a potentially deadly future.

READ MORE:

- The Fight to Commemorate a Massacre by the Texas Rangers: In 1918, a state-sanctioned vigilante force killed 15 unarmed Mexicans in Porvenir.

- White Terror on the Border: After an anti-immigrant shooting in El Paso, Texas’ GOP leaders blamed mental health and video games rather than gun laws and white supremacy.

- Otherness Among Us: The legacy of the Crystal City, Texas internment camps poses a difficult question about the balance between national security and personal liberty.