Above Photo: By Mason Adams/Getty Images

WHEN HEATHER EDWARDS’ CONTRACTIONS BEGAN THREE MONTHS EARLY, in March, she worried about the long drive to the hospital from her home nestled in the Appalachian Mountains in Jonesville, Va., a town of fewer than 1,000 people. Edwards, 32, was carrying quadruplets and hers was considered a high-risk pregnancy. The nearest hospital with a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) was an hour away in Kingsport, Tenn., Holston Valley Medical Center.

A decade ago she could have found an emergency room, if not a NICU, 10 minutes up the road at Lee County Regional Medical Center in Pennington Gap, Va., but the hospital closed in 2013 due to low community use, a lack of local physicians and Virginia’s refusal to expand Medicaid, which left the state’s rural hospitals to provide uncompensated care to uninsured patients. In 2012, the Lee County hospital was nearly $2.5 million in the red.

Neighboring counties do have emergency rooms, but none offered the NICU care Edwards needed. She decided to make the 44-mile drive along twisty mountain roads to Holston Valley Medical Center.

“If I went to [a different hospital], they were just going to fly me to Holston Valley or the [next] closest NICU,” Edwards says. “It would have been a waste of time.”

Edwards barely made it. Moments after she arrived, “everything just broke loose, and I went into labor,” Edwards says. “They tried to stop it and couldn’t. I had an emergency C-section.”

Edwards considers herself lucky. For the residents of rural Appalachia, long drives for emergency care are often a matter of life and death.

Lee County’s population reflects that of many rural communities in America: aging, mostly poor residents who struggle with long-term conditions that require ongoing, often expensive, care. The median household income in Lee County is $32,590—less than half of Virginia’s $68,766 and slightly more than half of the national $61,937. Lee County’s poverty rate is 28.2%, and about 12.5% of the county’s residents under 65 are uninsured, higher than the statewide average of 10.2%, and the population is aging, with all age groups except 65 and older in decline.

Despite the need, 113 rural hospitals have closed across the United States since 2010, according to the North Carolina Rural Health Research Program at the University of North Carolina. Another 673, about a third of those that remain, were at risk of closing in 2016, according to the National Rural Health Association.

“For me to drive five miles more to get access to hospital care is not a big deal,” says George Pink, deputy director of the North Carolina Rural Health Research Program. “But if you’re old or disabled, if you’re poor, traveling 4, 10, 16 miles—that could be a big enough barrier to forgo care.”

DOWNGRADING HEALTH

About six months after Edwards delivered her babies, on September 1, Holston Valley Medical Center’s NICU closed. On October 1, Ballad Health, the nonprofit that owns the hospital, also downgraded the trauma center from level 1 to level 3, meaning there would be fewer doctors and a smaller range of medical services. Now, the nearest level 1 trauma center and NICU are in Johnson City, Tenn., 66 miles from Jonesville; the next closest are 97 miles away in Knoxville, Tenn., 166 miles in Lexington, Ky., and 206 miles in Roanoke, Va.

Protests began outside the Holston Valley hospital May 2, the day after the state of Tennessee approved Ballad’s plans to close the NICU. Dani Cook, 46, joined because her granddaughter was born at Holston Valley weighing just over a pound; she learned about Ballad’s NICU plans a year and a day after her granddaughter came home.

“I jumped on Facebook Live and said, ‘That’s what happens when hospitals put profit over people, in this case babies,’” Cook says. She has been involved in the protest ever since. She posted a widely shared image on Facebook that lists distances from rural area communities to the closest level 1 trauma care center in Johnson City, along with the question, “Will you make it??!”

By late June, on the 58th day of the Holston Valley protest, Ballad banned Cook from the hospital grounds, with then-CEO Lindy White writing that Cook “repeatedly interfered with patient care by entering patient rooms, disagreeing with nurses and physicians over treatment plans.” As this issue went to press in early October, the protests have continued for more than 150 days.

Ballad has a virtual monopoly in the region, part of an emerging trend of rural hospitals owned by large nonprofits operating with little or no competition. With 21 hospitals serving 1.2 million people, Ballad dominates rural, economically depressed southwest Virginia and northeast Tennessee as the leading provider of inpatient hospital services.

Ballad emerged in 2018 from the consolidation of two competing nonprofits that ran up big debts: Mountain States Health Alliance and Wellmont Health System. Ballad’s Director of Communications Teresa Hicks says the debts were incurred due to wasteful and unnecessary duplication of services. The nonprofit received a Certificate of Public Advantage (COPA)—which allows states to approve mergers in exchange for various legal commitments—in Tennessee and a similar cooperative agreement in Virginia to escape federal oversight over potential monopoly problems, including effects on pricing, access and quality.

In Virginia, Ballad agreed to 49 conditions as part of its cooperative agreement, including a commitment to provide 11 “essential services” that include things typically found in a hospital, including emergency room stabilization. It was a victory of sorts for the Lee County Hospital Authority (LCHA), a group formed by the county board of supervisors in 2014 in an attempt to keep the hospital going.

As this issue went to press, Ballad officials said the Lee County hospital would reopen as an urgent care center in October, and as a critical access hospital by fall 2020, but the process has dragged on and locals remain skeptical.

Alan Bailey, who heads up Lee County E-911, a rescue squad dispatcher, says, “I’m not going to believe a word I hear out of the Ballad folks until I see the doors open and the people there.”

Even if the hospital’s emergency services return in 2020, J. Scott Litton Jr., 46, a Lee County native and member of the LCHA who has practiced as a family physician since 2003, says he doubts it will ever be what it once was. “We had a fully functional hospital with an intensive care unit, a medical surgeon and an operation surgical suite,” Litton says. “Probably what we’ll get … is an emergency room and some critical beds for access patients. But anyone requiring a cardiology consultation or surgical consultation is going to be transferred”—to Big Stone Gap, Kingsport, Johnson City or somewhere else.

In their merger application, Mountain States and Wellmont argued that consolidation was the only way to maintain high-quality, cost-effective care and local governance. In 2018, Ballad closed four urgent care centers—in Abingdon, Va., and Johnson City, Kingsport and Greeneville, Tenn.—where its predecessors had maintained competing facilities. In addition to downgrading the trauma level of the Holston Valley hospital in Kingsport, Ballad will downgrade another trauma center in Bristol, Tenn., in 2021.

Ballad officials contend these changes will enable it to survive in the fourth-lowest wage index area in the country while creating a better healthcare system. According to Ballad’s information sheets, the changes will “better integrate our highly-skilled trauma experts … to ensure assessment and rapid transport of patients to the center most appropriate for the patient’s needs.”

Cook and other local residents believe these changes will mean higher medical bills and a critical loss of care access. Multiple studies have consistently shown that hospital consolidations result in higher prices for services, at least for those with private insurance. Ballad’s Hicks says that, since the merger, charges for physician visits were reduced by an average of 17%, and a 77% discount for uninsured patients was adopted. Hicks also says Ballad has increased eligibility for free care, and offers no-interest payment plans as low as $50 per month.

Whether consolidation causes loss of access to services is more difficult to assess. Nonetheless, consolidation can result in confusion and frustration for patients as they adjust to changes in everything from drug prices to what services are offered at which facilities.

Teresa Allgood, 67, has seen her medical costs skyrocket since the Ballad consolidation. For four years, Allgood received infusions of INFeD every three or four months to treat her lupus and other autoimmune disorders at Kingsport Hematology and Oncology, known locally as Allendale. Each infusion took a day to administer and cost around $3,500, she says. Once Ballad took over, however, her regimen changed. Ballad enrolled in a federal drug discount program called 340B, at which point Ballad took Allgood off INFeD and put her on Feraheme. Feraheme infusions required coming in twice, seven days apart, and were much more expensive.

“The bill for the first infusion that Ballad was responsible for was $13,449.28,” Allgood says.

In late 2018, Ballad closed the Allendale facility and redirected patients to a new cancer center at Indian Path Community Hospital in Kingsport.

Ballad again changed Allgood’s medication, this time to Injectafer. Allgood received two treatments in March and says she is still waiting for the bill.

Although Allgood has now switched back to Feraheme treatments with a different provider, Tennessee Cancer Specialists in Johnson City, she expects her monthly insurance premium to increase because of the more expensive treatments.

“Folks end up in court with the attorneys from Ballad suing these people who never received a bill, and then their bills have been turned to collections,” Allgood says. Hicks says Ballad does not sue patients who have not received a bill.

Ballad filed 5,713 lawsuits against patients in its 2019 fiscal year, seeking payment for unpaid medical bills. In Virginia, Ballad first files a lawsuit against patients, which—if Ballad wins the case—allows it to more aggressively seek payment, sometimes by garnishing a patient’s wages.

Since October 2018, Ballad has filed 88 suits (plus 16 wage garnishments) against patients in Lee County. In neighboring Wise County, Ballad has filed 158 suits (plus 21 wage garnishments). When patients don’t appear in court, which is often, Ballad wins by default; when they do appear, they almost never have a lawyer.

Ballad is not the only nonprofit medical group to pursue debts via lawsuits. It’s a standard industry practice, and one carried out by both of its predecessor companies. To patients struggling on fixed incomes, though, it can feel like a punishment for falling ill.

A STATE OF DECLINE

Rural areas struggle to provide healthcare access for a number of reasons—including depopulation, a national nursing shortage and the departure of talented young people, which leave an older and poorer patient population than in urban areas. Access to health insurance is another issue. George Pink says rural hospitals tend to serve a bigger percentage of uninsured and Medicaid patients than urban hospitals.

Southwest Virginians have had access to only one insurer since 2017. For a brief period in 2018, it appeared that 58 localities, mostly in western Virginia, would be covered by no insurer in the federal marketplace at all, before Anthem eventually became the lone provider.

The majority of the country’s 113 rural hospital closures are clustered in the South, coinciding with the fact that few Southern states have expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, which provides extra federal funding to benefit rural hospitals. Despite Medicaid expansion’s popularity among voters nationwide, 13 Republican-dominated state legislatures in the South rejected Medicaid expansion over concerns about costs—and, arguably, to deny President Barack Obama a political victory.

The majority of the country’s 113 rural hospital closures are clustered in the South, coinciding with the fact that few Southern states have expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, which provides extra federal funding to benefit rural hospitals. Despite Medicaid expansion’s popularity among voters nationwide, 13 Republican-dominated state legislatures in the South rejected Medicaid expansion over concerns about costs—and, arguably, to deny President Barack Obama a political victory.Virginia lost two rural hospitals before it finally expanded Medicaid in January. Tennessee, which still has not expanded Medicaid, has seen 12 hospitals close since 2010.

A LONG WAY TO GO

Litton says before Lee County’s hospital closed, “we would have patients come to the office all the time who were short of breath, having chest pain—and we’d put them in a wheelchair and roll them down to the ER. Since the hospital closed, we’ve had to call the ambulance or call helicopters to get people to the care they need.”

Not all of those patients make it.

And without a hospital close by, Lee County’s volunteer rescue squads have much farther to travel. For much of the 70-mile-wide county, the nearest hospital is in Big Stone Gap, Va. In the westernmost end, it’s Middlesboro or Harlan, both in Kentucky.

The rural terrain adds to the travel time. “We have isolated areas with one road in and one road out,” says Lee County Sheriff Gary Parsons. “It may take you 45 minutes to get an ambulance in, and 45 minutes out before you hit a main road. That’s if you can even get an ambulance. If there are two crews [on duty], but they’re both taking people to hospitals somewhere else, you could have someone having a heart attack, the dispatcher begging for help—and an ambulance may still be an hour away.”

The county’s rescue squads have seen their time spent on each emergency call swell since the hospital closed. Jonesville Rescue Squad went from an average of 72 minutes to clear a call in 2012, the year before the hospital closed, to 112 minutes for the first eight months of 2019, according to data provided by Alan Bailey. The squad in Pennington Gap went from 63 minutes in 2012 to 101 minutes in 2019.

Ballad hospitals in southwestern Virginia also use ambulance diversion on a regular basis, according to regional Emergency Medical Services. Hospitals go on diversion when they don’t have enough beds or staff to treat new patients in a timely manner, meaning ambulances must take patients elsewhere except in dire emergencies. Hospital diversion has happened so frequently in recent months— including an incident in which three Ballad hospitals in close proximity went on diversion simultaneously—that the Southwest Virginia Regional EMS Council sent a letter in an attempt to relieve tensions between hospital staff and rescue crew volunteers. Hicks says the increased hospital diversion was due to staffing issues, and that diversion rates have since returned to normal.

“I could tell you story after story,” Litton says. “Joe Smith calls the ambulance because he’s having chest pain, and by the time the ambulance gets there and picks him up, Mr. Smith dies. That’s happened multiple times since the hospital closed. Honestly, would a hospital in the area have made a difference? Possibly.”

A SKY-HIGH PRICE

In a serious medical emergency, first responders often call helicopters to fly patients to a large, well-equipped hospital. Sometimes the flights are covered under insurance. In other cases, a patient could easily see a bill upward of $40,000.

Over the summer, Ballad signed a contract to partner with Med-Trans, an air ambulance company. Eric Deaton, Ballad’s chief operating officer, says Ballad has no control over what Med-Trans charges, but encourages employers to join the AirMedCare Network membership program, an insurance-like membership that protects against out-of-pocket transportation costs for select companies.

Gerri Kulakowsky, 73, lives in Rogersville, Tenn., a mountain town of about 4,300. When she woke up dizzy one night in November 2018, emergency responders put her on a helicopter to Johnson City Medical Center. Kulakowsky is deaf and says first responders misinterpreted her slurred speech as a stroke; the dizziness was caused by an inner-ear infection.

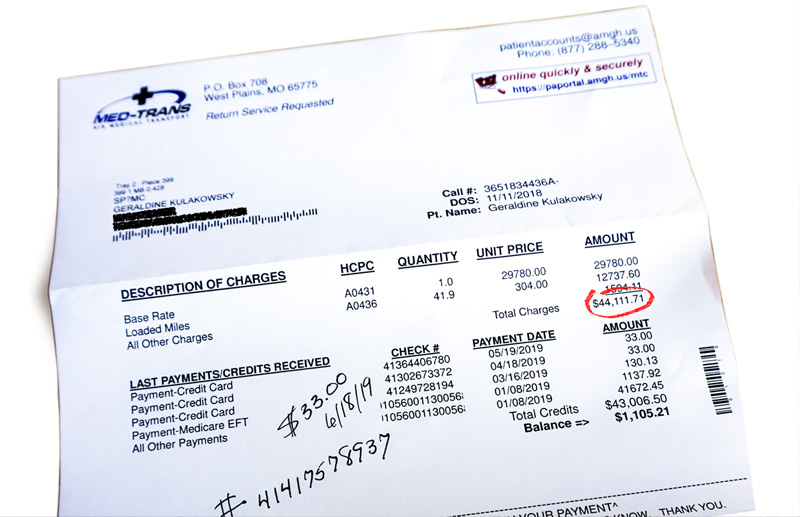

Kulakowsky did not have specialty insurance for air ambulances and received a $44,111.71 bill for the flight.

Congress held hearings this summer about surprise medical bills. A March 2019 study by the Government Accountability Office found that the median cost for privately insured patients of an air ambulance flight was $36,400, with most flights falling outside insurance networks, leaving patients on their own. The other major private air ambulance company serving people in southwestern Virginia is Air Evac Lifeteam, and then there’s the Virginia State Police. Patients in emergency situations don’t get to choose which helicopter picks them up—it often depends on a patient’s location, weather conditions and the helicopter’s estimated time of arrival—but if the state police arrive, there’s no charge. Even so, “the bill charges are not typically what a patient will pay,” says Shelly Schneider, public relations manager for Air Evac Lifeteam, likely because of insurance or settlements.

Kulakowsky still doesn’t understand her bill, which shows a mysterious credit for $41,672.45, even though she understands her insurance denied her claim.

Gerri Kulakowsky’s $44,111.71 bill for an air ambulance.

Legislation to address surprise bills and lower healthcare costs introduced by Sens. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Patty Murray (D-Wash.) has sat in a Senate committee since June. The law would require insurers to pay out-of-network providers the median in-network rate for surprise costs like air ambulances. In response, Global Medical Response, the parent company of Air Evac Lifeteam, Med-Trans and AirMedCare Network, spent nearly $900,000 on ads, many targeting Tennessee and Kentucky, urging people to call their senators and ask them to “protect access to air medical services.”

WHAT TO DO

Following the Ballad merger, Tennessee established the COPA Local Advisory Council to collect community input and to hold forums for public comment on Ballad’s annual report. In February, the council held a public hearing in Blountville, Tenn., in which physicians and activists expressed concerns about the merger and its effect on regional healthcare. In September, Virginia created a similar task force. The Federal Trade Commission also held a public workshop in June to assess the impact of COPAs.

Ballad’s virtual monopoly has also emerged as an issue in a nearby Virginia state house district race. Starla Kiser, a physician with a Norton clinic, is running as a Democrat for an open seat against Republican lawyer William Wampler III, who worked for a consulting firm that helped Ballad’s underwriters refinance its debt after the merger (although Ballad says Wampler himself was not involved). Kiser wrote an op-ed criticizing Ballad and expressing her “fear that patient fatalities will increase due to the lack of local care during a medical emergency.” Kiser faces an uphill battle in a district where Trump won 77% of the vote.

While healthcare politics plays out at the state and federal level, clinics and healthcare providers have sprouted up to fill gaps and provide basic care in southwestern Virginia.

Stone Mountain Health Services operates a number of regional clinics that offer a sliding scale for patients. The Health Wagon, founded by a nun in 1980 operating out of a Volkswagen Beetle, runs mobile clinics used by many regional residents, some of whom are managing long-term ailments like diabetes and heart conditions. And Remote Area Medical, based in Rockford, Tenn., runs free clinics providing dental, vision and medical services to thousands of Appalachians.

Ballad points to one of its rural Tennessee hospitals as a “great prototype” for healthcare’s future in the region, replacing an aging hospital in Unicoi with a new facility with fewer but targeted services and an ER. Ballad COO Deaton says it is “busier than when we had an older facility, because it meets the needs of the population.” Ballad was also required to keep it open as part of its COPA agreement with Tennessee.

Ballad’s new Unicoi facility does address a key reason why rural hospitals close: their inability to invest in new equipment and services to keep patients coming to their local hospitals, instead of bypassing them for more modern facilities.

Overhauling America’s health insurance system with a single-payer Medicare for All system could curb rural hospital closures, says Adam Gaffney, a critical care physician who teaches at Harvard Medical School and serves as president of Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP).

“There are real challenges to providing comprehensive healthcare in sparsely populated areas that basically every nation faces (including attracting needed personnel) that don’t entirely disappear,” Gaffney cautions. “However, one critical reason for closures and disparities in access is resolved: the fact that healthcare infrastructure follows profits.”

PNHP recommends that in a single-payer system, the federal government provide each hospital a guaranteed global budget to cover operating costs. (This provision is included in the House Medicare for All bill, but not the Senate’s.) Hospitals wouldn’t have to rely on bringing in net revenue— or what nonprofit systems refer to as “operating margins”—to cover investments in new technology, services and facilities.

“In our current system, if you don’t have operating margins, you can’t get the MRI machine or the new ward you need,” Gaffney says. “If your competitor has these new facilities and services, you’re going to start hemorrhaging patients. That’s the essential issue” behind hospital closures.

He notes Medicare for All would solve another major factor in closures: the lack of reimbursement from uninsured patients or those with lower-paying insurance. Government insurance would also protect such patients from shocking bills.

In September, Alexa Begley, 26, friend and coworker of Heather Edwards, was in the midst of her own high-risk pregnancy, due October 17. She had been seeing an OBGYN at Holston Valley. Begley learned, however, that in the wake of the NICU closure, her doctor would no longer deliver babies there as of October 1, meaning Begley would need to travel 63 miles from her home in Pennington Gap to Johnson City to give birth—an hour and a half drive.

“With it being my third pregnancy, you never know how fast the baby can get here,” Begley said. “It’s scary. You may be delivering in the car.”

For better or worse, Begley delivered her baby early, on September 20, at Holston Valley, just 11 days before her doctor moved.

As Ballad and other rural health systems try to serve rural patients without running million-dollar deficits, Begley, Edwards and other residents of southwestern Virginia are left with a sense of powerlessness and uncertainty—not just for themselves, but for their children.

How do you get up each day with that hanging over you? “You just take it as it comes,” Begley shrugs.