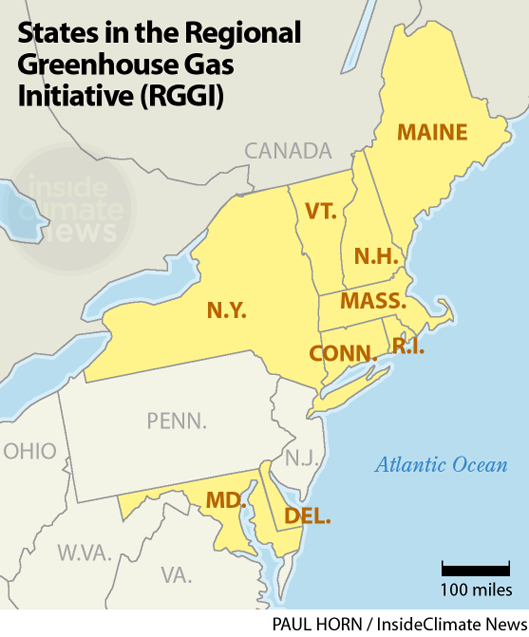

Above Photo: The states in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, or RGGI, broke new ground when they launched the nation’s first carbon cap-and-trade program in 2009. Credit: Todd Van Hoosear/CC-BY-SA-2.0

Five of the states have Republican governors. The RGGI proposal follows California’s vote to extend its cap-and-trade program to fight climate change.

Nine eastern states announced Wednesday that they have agreed on a proposal to cut global-warming pollution from the region’s power plants an additional 30 percent between 2020 and 2030.

The compact of Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic states known as the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) has worked for two years to hammer out the next step in their landmark emissions cap-and-trade program, which puts a price on carbon dioxide emissions from the production of electricity. The program has a track record of cutting emissions fairly painlessly across a densely populated section of the country.

Advocacy groups and policy makers have been closely watching the outcome of the negotiations. The RGGI states’ decision on how to move forward, which still must be finalized, is seen as a test case of states’ commitment to cut greenhouse gas emissions as the Trump administration attempts to dismantle federal climate policies, including the Clean Power Plan that was the Obama administration’s plan for controlling power plant emissions.

The RGGI states—with five Republican governors and four Democratic governors—together represent the world’s sixth largest economy, with $2.8 trillion in GDP. California, where the legislature recently voted to extend its own cap-and-trade program through 2030, falls just behind in GDP, at $2.5 trillion.

Despite the bipartisan support for the proposal announced Wednesday, Republican administrations in three states—Maine, New Hampshire and Maryland—had previously expressed concern about the costs of more stringent cuts. In 2011, New Jersey’s Republican governor, Chris Christie, withdrew his state from the coalition.

Ultimately, the RGGI states agreed to pursue one of the more ambitious proposals on the table, which calls for lowering emissions caps each year by 3 percent over the previous year. Under the current plan, their commitment is to lower the cap by 2.5 percent a year. Under the agreed upon proposal, power sector emissions would be 65 percent lower by 2030 than they were 2009, RGGI’s inaugural year.

By allowing utilities to trade emissions credits, RGGI encourages lower-cost solutions and also generates revenue for the states, which have used the money for energy conservation and other popular programs.

“Maryland is committed to finding real bipartisan, common-sense solutions to protect our environment, combat climate change and improve our air quality,” Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan, a Republican, said in a statement following the announcement Wednesday.

Environmental Groups See Pros and Cons

Many environmental groups applauded the choice—and the model more broadly—as a workable, market-based approach in the absence of leadership at the federal level.

“With the Trump administration making every effort to turn back the clock on environmental progress, it falls to state and regional collaboration to lead the way in protecting public health and defending clean air and water,” said Phelps Turner, an attorney with the Conservation Law Foundation. “For nearly a decade, RGGI has been a sterling example of the positive impact such collaboration can have on both the environment and the economy, and today’s new commitments represent a significant contribution to our work to leave a cleaner and safer home for future generations.”

Critics of the cap-and-trade model lashed out at the proposal.

“The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) is based on the dubious notion that a market-based system can reduce the carbon emissions that are driving the climate crisis,” said Jim Walsh, renewable energy policy analyst for Food & Water Watch, in an emailed statement. “The states participating in RGGI must create real energy programs that tackle emissions head-on with hard caps on pollution, instead of tinkering around the edges with corporate-friendly pollution credit schemes.”

According to a recent analysis by the Acadia Center, carbon dioxide emissions from the RGGI states have fallen more than 40 percent compared to 2008 levels. In 2016, their annual CO2 emissions fell to just under 80 million tons.

The RGGI group says the proposed caps will cut carbon emissions an additional 132 million tons by 2030, equivalent to taking 28 million cars off the road for one year.

Other regions across the country have seen lower carbon emissions, largely driven by low-cost natural gas. But a study by the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions and the Duke University Energy Initiative found that, in the RGGI states, the primary reason for lowered emissions was the cap-and-trade market.

How Cap-and-Trade Lowers Emissions

Under the RGGI model, the coalition sets a cap on carbon pollution that declines each year. Each year, states sell a decreasing number of permits—or allowances—at auction. Power plant operators purchase the allowances or trade them in the marketplace, enabling them to remain under the cap. The proceeds from the auctions are rolled into energy efficiency and renewable energy initiatives and programs.

If the RGGI states fail to lower the pollution cap, there is a danger that carbon credits on the RGGI market would continue to be priced so cheaply as to undermine the effort. Thanks largely to low natural gas prices and the declining costs of renewable energy, more allowances were being sold than the market could absorb, creating a surplus of allowances and driving down auction prices. Power generators banked some of those allowances, creating a scenario where they could potentially use the allowances to pollute beyond the 2020 cap.

The proposal agreed upon and announced Wednesday includes two mechanisms aimed at remedying the problem.

One of those would lower the post-2020 cap by the amount of excess allowances banked in the years leading to 2020, which the Acadia Center has estimated could prevent nearly 50 million tons of carbon pollution. The other would automatically lower the cap, by up to 10 percent a year, if allowances fall below expected levels.

The member states—Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island and Vermont—will hold a stakeholder meeting on Sept. 25 in Baltimore, where they plan to discuss further details of the proposal.