Sweden’s 32 waste-to-energy incineration plants are working so efficiently, the country must import garbage from other EU countries. | Handout

There’s a “recycling revolution” happening in Sweden – one that has pushed the country closer to zero waste than ever before. In fact, less than one per cent of Sweden’s household garbage ends up in landfills today.

The Scandinavian country has become so good at managing waste, they have to import garbage from the UK, Italy, Norway and Ireland to feed the country’s 32 waste-to-energy (WTE) plants, a practice that has been in place for years.

“Waste today is a commodity in a different way than it has been. It’s not only waste, it’s a business,” explained Swedish Waste Management communications director Anna-Carin Gripwell in a statement.

Every year, the average Swede produces 461 kilograms of waste, a figure that’s slightly below the half-ton European average. But what makes Sweden different is its use of a somewhat controversial program incinerating over two million tons of trash per year.

It’s also a process responsible for converting half the country’s garbage into energy.

“When waste sits in landfills, leaking methane gas and other greenhouse gasses, it is obviously not good for the environment,” Gripwell said of traditional dump sites. So Sweden focused on developing alternatives to reduce the amount of toxins seeping into the ground.

Importing garbage for energy is good business for Sweden from Sweden on Vimeo.

Before garbage can be trucked away to incinerator plants, trash is filtered by home and business owners; organic waste is separated, paper picked from recycling bins, and any objects that can be salvaged and reused pulled aside.

By Swedish law, producers are responsible for handling all costs related to collection and recycling or disposal of their products. If a beverage company sells bottles of pop at stores, the financial onus is on them to pay for bottle collection as well as related recycling or disposal costs.

Rules introduced in the 1990s incentivized companies to take a more proactive, eco-conscious role about what products they take to market. It was also a clever way to alleviate taxpayers of full waste management costs.

According to data collected from Swedish recycling company Returpack, Swedes collectively return 1.5 billion bottles and cans annually. What can’t be reused or recycled usually heads to WTE incineration plants.

In Helsingborg (population: 132,989), one plant produces enough power to satisfy 40 per cent of the city’s heating needs. Across Sweden, power produced via WTE provides approximately 950,000 homes with heating and 260,000 with electricity.

Recycling and incineration have evolved into efficient garbage-management processes to help the Scandinavian country dramatically cut down the amount of household waste that ends up in landfills. Their efforts are also helping to lower its dependency on fossil fuels.

So if Sweden burns approximately two million tons of waste annually, that produces roughly 670,000 tons worth of fuel oil energy. And the country needs that fuel to operate its well-developed district heating networks which heat homes in Sweden’s cold winters.

This is why the country has taken advantage of the fact a number of European nations don’t have the capacity to incinerate garbage themselves due to various taxes and bans across the EU that prevent landfill waste. There’s where Sweden comes in to buy garbage other countries can’t dispose of themselves at a reasonable cost.

According to a study in the journal of Environmental Science and Technology, more than 40 per cent of the world’s trash is burned, mostly in open air. It’s a process markedly different from the regulated, low-emission processes Sweden has adopted.

Start-up costs for new incineration plants can get pricey and out of reach for some municipalities depending on the integration of processes used to filter ash and flue gas byproducts. Both contain dioxins, an environmental pollutant.

The incineration process isn’t perfect, but technological advancements and introduction of flue-gas cleaning have reduced airborne dioxins to “very small amounts,” according to the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency.

Unless manufacturers stop making products with materials that can’t be reused or tossed into incinerators, a 100 per cent recycling rate is unlikely to be achieved in our lifetime. Goods that are or contain tile, porcelain, insulation, asbestos, and miscellaneous construction and demolition debris can’t be burned safely; they have to be dumped in landfills.

“The world needs to produce less waste,” explained Skoglund.

Sweden’s success handling garbage didn’t come overnight — the latest results are the fruits of a cultural shift decades in the making.

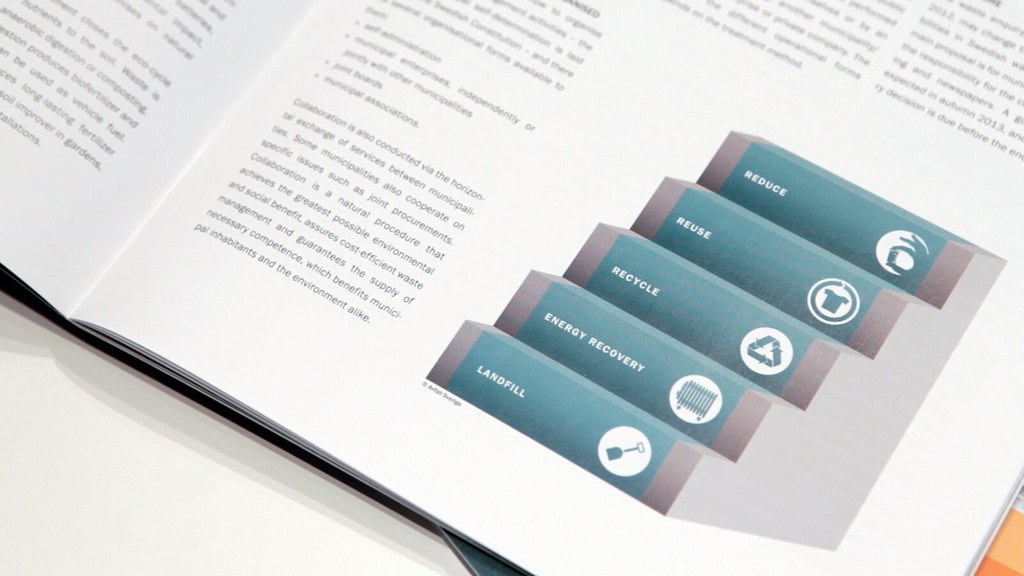

“Starting in the ‘70s, Sweden adopted fairly strict rules and regulations when it comes to handling our waste, both for households and more municipalities and companies,” Gripwell told HuffPost Canada, referring to the country’s “waste hierarchy” now ingrained in Swedish society.

“People rarely question the ‘work’ they have to do,” she said.