Above Photo: Life-sized models of a tank and surface-to-air missile launcher are positioned near a training range to simulate a battleground environment. Jon Letman

Pohakuloa Training Area, an Army-controlled site the size of Guam, is the largest U.S. military training ground in the Pacific.

POHAKULOA, Hawaii Island — It’s cold, it’s windy and at 6,300 feet above sea level, the air is thin. For more than 70 years, this stark landscape of folded black lava and bulging cinder cones has been where the U.S. military prepares for war on Hawaii Island.

This is Pohakuloa Training Area, the U.S. military’s largest training grounds in the Pacific.

Established as a live-fire range for U.S. Marines during World War II, PTA has fallen under the domain of the Army since the mid-1950s. The area is used to practice unloading troops, firing weapons and other battle maneuvers — and also serves as a training ground for other militaries around the globe.

“Sweat in training is far more preferable to blood lost in fighting,” said Army public affairs officer Eric Hamilton, adding that the training is central to PTA’s core mission.

But he conceded it’s also at odds with the world view of many in Hawaii. Some activists consider continued military control at PTA a desecration of the land, and are fighting in particular, to end live-fire training.

Lakea Trask, a Puna resident, said that in a world ravaged by militarism and violence, Hawaii should be a kipuka (oasis) of aloha for teaching peace.

“Instead of being the training grounds for war, why not the training grounds for cleaning up that war or healing that relationship?” Trask asked.

A Training Area As Large As Guam

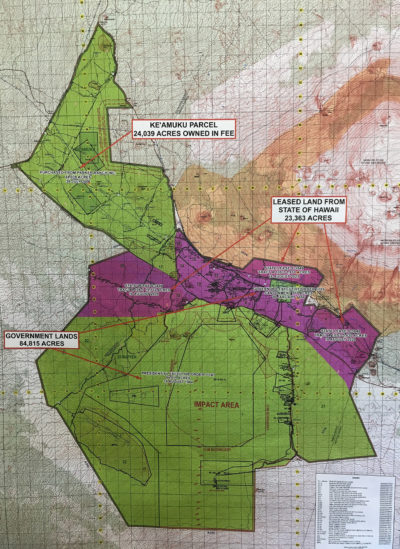

PTA is comprised of Hawaiian Kingdom government and crown lands seized by U.S. government executive order, along with a 24,000-acre parcel purchased from Parker Ranch, and a third parcel leased from the state of Hawaii for the amount of one dollar for 65 years. Occupying 133,000 acres (207 square miles), PTA is as large as the island of Guam.

Inside PTA’s cantonment area, Hamilton explained how rows of weather-beaten Quonset huts dating back to the Korean War are used as barracks, offices, a theater, a chapel, a mess hall, a gymnasium, even a Domino’s Pizza outlet.

Driving along a bumpy road to the training sites, Hamilton said PTA allows soldiers and marines to practice as if they were deployed.

“Everybody can work with their assigned weapons system in an area where they’re not facing life or death,” he said. “They can afford to make mistakes.”

Training includes everything from sniper practice to throwing grenades, firing vehicle-borne armaments, torpedoes, mortars, artillery and munitions.

Soldiers and marines practice operating assault vehicles, surveillance drones and aircraft like helicopters and MV22 Osprey. B-2and B-52 bombers have also flown from as far away as Guam and Missouri to drop dummy bombs on Pohakuloa.

The Hawaii County Police Special Response Team also regularly conducts small arms and tactical training at PTA in a mock village that allows for live-fire and simulated munitions drills.

Additionally, PTA is used for training by as many as eight foreign militaries during the biennial Rim of the Pacific maritime warfare exercises, which runs this year from June 27 to Aug. 2, primarily in Hawaii and, to a lesser extent, Southern California.

Conservation Or Desecration?

PTA critics consider the installation a violation of the land, a threat to the environment and lacking legal legitimacy. Live-fire training, they say, is an affront to Hawaiian culture and spirituality.

Describing how Tutu Pele (the Hawaiian volcano goddess, Pele) gives birth to new land while leaving kipuka (unaffected areas of forest from where life begins anew), Lakea Trask stood on a Kalapana lava flow from the 1990s and denounced what he sees as a gross misuse of Hawaii’s land.

“They learn how to kill, spill and bill right here,” said Trask, referring to violence, pollution, and the financial burden of war.

“We don’t want that imprint on the rest of the world … (They’re) putting the blood on our hands and the hands of our ancestors.”

Trask wants an end to all live-fire training and has a message for the military: “Help us, your next door neighbors, rebuild our communities and install environmental safeguards and protections instead. Use your equipment and muscle for something good. Make Hawaii a center of healing and peace for the world.”

Good News Stories

When the military holds public hearings related to PTA, residents frequently unleash strong criticism, but Deputy Garrison Commander Gregory Fleming countered that PTA is a respected community member and plays an important role in protecting the environment.

Fleming pointed to nearly 200 civilian jobs, cultural and natural resources programs with a combined budget of up to $7 million and an active recycling center.

“It’s just not about the military training here. It’s how we take care of the land,” he said. “We’ve got a lot of good news stories. We’re very happy with that.”

Besides replacing the aging Quonset huts with more permanent structures and burying an upgraded electric system underground, Fleming said renewing the lease or otherwise acquiring the 23,000-acre parcel of state-leased land before the August 2029 deadline is a top priority.

That parcel is home to ammunition storage and holding areas, a battle area complex and firing points for artillery and mortars. Losing access, Fleming said, would greatly diminish the training value of PTA.

Breach Of Trust

In April, a Honolulu Circuit Court judge ruled that the state had failed to fulfill the obligations of the PTA lease, specifically to malamaaina or care for the land.

One of the suit’s co-plaintiffs, Clarence Ku Ching, said that while he sympathizes with individual soldiers, he is a “pro-peace, anti-military guy” opposed to sacred land being used for “getting ready to make war and go kill people.” He called the ruling a “big win for the aina.”

In a statement following the ruling, the Department of Land and Natural Resources said, “We appreciate that this proceeding brought further focus to regular inspections and ongoing work with the Army to properly steward the leased lands. This work has already been under way for several years.”

Out Of Sight, Out Of Mind

One of PTA’s most prominent critics is longtime activist Jim Albertini, founder of the Malu Aina Peace Center near Hilo. Speaking over the din of coqui frogs and pounding rain, Albertini said, “What’s going on (at PTA) is training to do to others what has been done to Hawaii.” He means invasion, occupation, and militarization.

Albertini noted that in 2008 the Hawaii County Council adopted a resolution in an 8-1 vote calling for a “complete halt” to live-fire testing at PTA until the potential hazards posed by depleted uranium (DU) were addressed.

Earl DeLeon was part of the aloha aina movement in the 1970s that helped end live-fire training on Kahoolawe. He says the live-fire training on Hawaii Island must also end.

Earl DeLeon was part of the aloha aina movement in the 1970s that helped end live-fire training on Kahoolawe. He says the live-fire training on Hawaii Island must also end.

Jon Letman

In 2007 the military confirmed that DU had been used as fins on M28/M29 Davy Crocket training munitions at PTA between 1965-1968.

The threat DU may pose demands further investigation Albertini said, but PTA spokesman Hamilton insisted the Army has been forthcoming in addressing the matter.

Hamilton dismissed the idea of DU blowing in the wind as an “egregious fallacy” stemming from a “real lack of understanding about what happens here and what did happen here.”

DU was used by the military in Hawaii before the National Environmental Policy Act was introduced, Hamilton pointed out, and said no special records were kept and over time knowledge of whether DU had been used at PTA or Schofield Barracks was lost. “The Army is presuming that it could have been used here and we have reacted accordingly,” he said.

Let It Burn

As a federal agency, the Army is required to comply with the Endangered Species Act as well as analyze live-fire training and other activities that could impact endangered species within PTA.

Lena Schnell, senior program manager for PTA’s Natural Resources Office, explained that she and her crew of 30 civilians are employed through a cooperative agreement between Colorado State University and the Army to monitor threatened and endangered species like Hawaii’s native hoary bat, hawks, seabirds and 20 federally protected plants endemic to Hawaii.

PTA is used by every branch of the military and also, during Rim of the Pacific exercises, foreign military units for training with most available weapon systems and armored vehicles.

“If some of the Army actions are going to cause a rapid decline or continue to move species toward the brink of extinction, then the Fish and Wildlife Service will issue what is called a jeopardy opinion,” Schnell said.

“If the Army can step in and say we know our actions cause fires, therefore if we fence these areas and we move the ungulates and have more of those species, if we have a fire that impacts a smaller part of the range, we still won’t cause an extinction.”

Schnell said this strategy helps endangered species populations grow and recover while reducing the damage of accidental impacts.

“Different training events come with certain fires risks,” Schnell said. “It seems like whenever there’s big training events, fires in the impact area happen.”

When munitions or artillery start fires inside the impact area, the fires are left to burn out on their own. That area of PTA is a “no-go zone” but, Schnell said, the area is mostly devoid of vegetation.

Schnell said the Army is committed to wildlife conservation but conceded protecting natural resources while achieving the Army’s primary mission (training for war) is a “tough sell.”

“That’s a difficult thing to do because (Army) training missions … can be disruptive to the landscape,” she said, adding that the Army works hard to strike a balance with “conserving and preserving training assets.”

They’re ‘Hurting Our Mother’

Kealakeua resident Earl DeLeon doesn’t buy the conservation argument.

“You’re kidding me. I’m going to slap my mother in the face and she’s not going to be sore? She’s not going to hurt?” DeLeon said. “That’s our mother you’re talking about. You’re hurting our mother, even one part. If you hurt her leg, her arm, that’s part of her body. It’s real simple … The truth is the truth, period. You cannot deviate from the facts.”

“To me it’s hilarious because if you speak conservation and you be bombing the land, that is the conflict of interest.”

DeLeon was one of the Native Hawaiians who occupied Kahoolawe as part of the aloha aina movement in the 1970s. He remembers walking along Kahoolawe’s coastline covered in undetonated explosives.

Eventually live-fire training on Kahoolawe was stopped and now it’s time to stop bombing Pohakuloa, DeLeon said.

We’re Not ‘Bombing The Aina’

But what many refer to as “bombs” are, in fact, very targeted precision munitions, according to PTA’s Hamilton. He explained how the Army goes to great lengths to minimize impacts and reduce noise.

That said, Hamilton acknowledged sound carries, especially during helicopter night training saying, “Wherever there’s loud aircraft there’s going to be some impact on folks.” But he was adamant, “We are not bombing.”

Ruth Aloua lived three years at Waikii Ranch, just five miles from PTA. Aloua remembers falling asleep to the sound of bombs and helicopters. Some mornings, she awoke to the sound of explosions shaking the house.

As a farmer and kiailoko (fishpond guardian), Aloua disputed the Army’s claims of conservation, asking: “If they’re going to present such an argument … as ‘oh, we don’t bomb as much as we preserve,’ why are (they) even bombing at all?”

She said the military has no legal authority to claim jurisdiction over Pohakuloa and that her people, Kanaka Maoli, were never asked if they wanted their land to be used for war training.

The fact that more people don’t speak out, Aloua said, is evidence of how militarization has been normalized and people are afraid to publicly oppose the army.

But she’s hopeful things are starting to change.

“I’m always reminding myself, Pohakuloa is at the base of Mauna Kea and so it is Mauna Kea,” she said.

She sees a clear connection between protecting sacred land from development at the top of the mountain, stopping live-fire testing and safeguarding the environment for all life downstream mauka to makai.

The struggle against the proposed Thirty Meter Telescope on Mauna Kea activated and motivated younger generations, Aloua said, and now it’s time to harness that courage to stop live-fire testing at Pohakuloa to protect the water and land of Moku O Keawe — Hawaii Island.

Aloua continued, “For me, if I was the military, I would be frightened … because a lot of us are very young, we’re very smart, a lot of our keiki coming up are going to have more tools than us.”

“The mountain keeps just reigniting us, reaffirming who we are, what we know, what we’re doing, why we’re doing it,” Aloua said. “When we go down slope and whether we come up slope, it all brings us back to our mountain, our main mountain.”