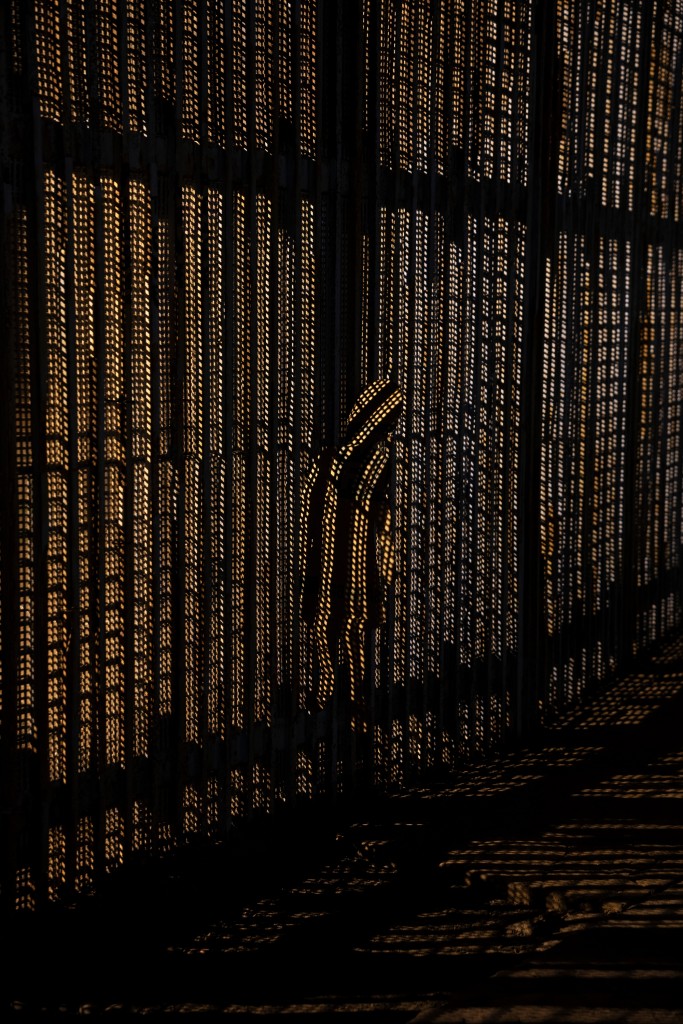

Above Photo: A man stands by the end of the U.S.-Mexico border wall in Tijuana, Mexico, on Dec. 23, 2018. Photo: Kitra Cahana

FOUR PHOTOJOURNALISTS GATHERED on the southern side of the U.S.-Mexico border wall shortly after Christmas in Tijuana. They were there to document the arrival of the migrant caravans from Central America, the latest chapter in a story that had drawn President Donald Trump’s increasing outrage.

As the photographers waited in the dark, a pair of Mexican police officers approached.

The officers wanted to know the photographers’ names and where they were from. They asked to see their passports and photographed the travel documents once they were handed over.

The photographers represented multiple nationalities and included American citizens and international award-winners contributing to the world’s best-known news organizations. They were an experienced crew, and, to a degree, were accustomed to being documented as they did their work. Still, having their passports photographed by Mexican cops was unusual.

In the weeks that followed, each of the photographers at the wall that night found themselves pulled into secondary screenings by U.S. and foreign officials while attempting to cross borders in multiple countries. In one case, a photojournalist was barred from re-entering Mexico. During questioning, a U.S. official later indicated that he knew about her encounter at the wall. In another case, a photojournalist was taken into a private room at a U.S. port of entry, shown a book full of images of border-based activists, and asked who he knew.

A Border Patrol officer uses his cellphone to take photos of journalists after a Mexican migrant and her daughter jumped the border fence to get to San Diego, Calif., from Tijuana, Mexico, on Dec. 29, 2018.

Photo: Daniel Ochoa de Olza/AP

In early January, a second group of photojournalists was approached by Mexican police while working near the wall. Again, their passports were photographed. When one of the photographers asked the officers why they were taking the photos, the answer that came back was “for the Americans.”

By the end of the month, at least one of those photojournalists had also been barred from re-entering Mexico.

Last week, two attorneys with a leading legal organization challenging the Trump administration’s border crackdown were denied entry into Mexico. In a press conference, the lawyers — Nora Phillips and Erika Pinheiro, senior litigators with the Los Angeles- and Tijuana-based organization Al Otro Lado — blamed the U.S. government for their removal. Pinheiro, a U.S. citizen living in Mexico, was heading home to her 10-month-old son. Phillips, Al Otro Lado’s legal director, was on her way to a long-planned vacation with her husband, her 7-year-old daughter, and her best friend when she was flagged by officials at the Guadalajara airport. She spent nine hours in detention without food or water.

“It was literally just hell on earth,” Phillips said in an interview with The Intercept.

The attorneys’ expulsion was the latest in a series of escalating tactics used by U.S. and Mexican law enforcement to target legal service providers, humanitarian groups, and journalists on the border.

Through interviews with journalists and advocates who have worked in the Tijuana area recently, The Intercept has uncovered a pattern of heightened U.S. law enforcement scrutiny aimed at individuals with a proximity to the migrant caravans.

Nineteen sources described law enforcement actions ranging from the barring and removal of journalists and lawyers from Mexico, to immigrant rights advocates being shackled to benches in U.S. detention cells for hours at a time. Multiple sources, including members of the press and advocates, described being forced to turn over their notes, cameras, and phones while plainclothes U.S. border officials pumped them for information about activists working with members of the caravans.

Secondary screenings in the San Diego area have become so routine, one source said, that he has taken to leaving several hours early for his cross-border trips, anticipating being held by U.S. border guards. The freelance photojournalists swept up in the dragnet, meanwhile, have been left to worry about whether they will be able to freely continue their profession, or if state interference — in some cases from their own government — will prevent them from documenting some of the most important stories of the Trump era.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the agency responsible for U.S. ports of entry, has denied responsibility for the immigration attorneys’ denied entry into Mexico. The Intercept sent CBP a series of questions on Monday regarding the targeting of journalists, lawyers, and immigration advocates. The agency did not provide responses on the record. The Mexican government did not respond to a request for comment.

Responding to The Intercept’s findings, Alex Ellerbeck, North America program coordinator for the Committee to Protect Journalists, and lead author of a recent report on CBP searches involving journalists, said that while “CPJ has documented dozens of cases of journalists asked about their work in secondary screening or asked to hand over their devices … the sheer number of cases back to back in a single point of entry and the incredibly blatant attempts to get journalists to act as informants for the government stand out as an escalation.”

“The government can’t use the border to prevent journalists from gathering information, especially on issues it would rather they not report on,” Hugh Handeyside, a senior staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Security Project, told The Intercept. “If CBP is interfering with or retaliating against journalists, that raises serious constitutional questions and bears further investigation.”

At least one U.S. lawmaker is already investigating.

Sen. Ron Wyden’s office confirmed to The Intercept the opening of an investigation into CBP’s newly revealed border crackdown, including specifically the barring of an American journalist’s re-entry into Mexico to continue her work.

“These are extremely disturbing reports,” Wyden said in a statement to The Intercept. “It would be an outrageous abuse of power for the Trump Administration and CBP to target people for searches based on their political beliefs or because they are journalists. CBP needs to explain exactly what happened in these cases, and whether this was an aberration, or a coordinated effort to punish political opponents.”

Migrants, journalists, and U.S. activists run from tear gas on Jan. 1, 2019, after U.S. authorities fired tear gas over the border wall in Tijuana, Mexico.

Photo: Kitra Cahana

The New Year’s Gassing

In the first hours of 2019, as many Americans were still ringing in the new year, a dramatic display was unfolding on the U.S.-Mexico border.

On one side of the wall separating Tijuana from San Diego were roughly 150 migrants, including women and children; a small group of American activists; and press from around the world. On the other side, in a dirt lot, was a considerable contingent of well-armed border guards.

CBP later claimed that what happened next began with rocks being thrown, which required the use of three volleys of tear gas and an unknown number of pepper-pellet rounds fired over the border. The Associated Press, however, reported that rocks were not thrown until after the gas canisters were launched.

By all accounts, the scene was chaotic, with white plumes of noxious smoke rising into the air, and migrants running to and from the border wall.

Kitra Cahana, a freelancer with dual U.S. and Canadian citizenship, was one of the photojournalists on the ground that night. Though she was shot in the leg with a nonlethal round, she continued on undeterred; her work at a migrant shelter days later was published on the front page of the New York Times. Cahana was also one of the four photojournalists whose passports were photographed by Mexican law enforcement days earlier.

Cahana arrived in Tijuana in late November, following the exodus of thousands of Central Americans who crossed Mexico before filtering into the border city. Like many of the photojournalists covering the caravan, she gravitated to the border wall and was soon shooting photos there on a daily basis. By late December, Cahana told The Intercept, the Border Patrol’s interactions with the photographers there were becoming increasingly hostile. By day, agents would snap photos of the press. At night, they would shine blinking flashlights capable of destroying a camera’s sensor at the photojournalists’ cameras as they worked.

Cahana left Tijuana in early January. She flew home to Quebec for a quick assignment, with plans to return to Mexico days later to continue her coverage of the migrant caravans. Cahana began her second journey on January 17, attempting to travel to Tapachula, Mexico, where a new caravan was set to take off, via Detroit, Michigan. That’s when the trouble started.

When Cahana put her American passport through the check-in machine at the Montreal airport, it printed out an image of her face with a huge X on it. Cahana approached an airport official, explaining what had happened. When Cahana told the official that she was a photojournalist heading to Mexico to cover the migrant caravan, she was taken to a back room to wait. A second official questioned Cahana about her assignment and how she made money, but eventually let her go to board her flight.

It was a little after 8 p.m. when Cahana landed in Mexico City. After telling Mexican customs officials of her plans to head to Tapachula, Cahana was taken to another back room, where she would begin 13 hours of cold, incommunicado detention.

Though conversational in multiple foreign languages, Cahana was a beginning Spanish speaker and struggled to understand what was happening. Her phone was confiscated and her requests for an interpreter, or contact with embassy officials, went nowhere. She worried about the photos on her hard drive being accessed — they included images of vulnerable asylum-seekers. Cahana was given an unofficial-looking document — later shared with The Intercept — consisting of 27 basic questions written in English. She quickly filled it out.

Cahana asked if she was being detained because she was a journalist.

Left/Top: An art installation featuring a cardboard cutout of a girl stands at the U.S.-Mexico border wall near Friendship Park on Dec. 23, 2018, in Tijuana. Right/Bottom: Maryuri Celeste, 18, from Santa Rosa de Copán, Honduras, photographed in Tijuana on Nov. 30, 2018.Photos: Kitra Cahana

“No, it’s not us,” she recalled a Mexican official saying. “It’s Interpol.”

“Interpol?” Cahana asked. “Yes,” the official said.

“Los americanos?” Cahana asked. “Yes,” the official replied.

Hours ticked away. After midnight, Cahana was taken to a separate room and urged to sign a Spanish-language document that would authorize her removal to the U.S. “Just sign here. I’m trying to help you. If you don’t sign, you will not be allowed to come back to Mexico for five years,” she recalled a Mexican official saying. Still without a translator, or any real explanation as to why she was being detained, Cahana refused to sign.

She was moved to a multiroom holding area where people were sleeping on mats on the floor. An official with Aeroméxico told her that she would be flown to Detroit in the morning. When she asked if she could be flown to Montreal instead, offering to pay her own way, she was told that would not be possible. While in detention, Cahana befriended a woman from Spain who spoke English.

Together with the woman, she spoke to a Mexican official overseeing the holding area. Cahana asked him if she could speak to someone from her embassy or someone who at least spoke good English. The man told her no. She again asked if she was being detained because she was a journalist. The man said it was because of the Americans, Cahana recalled, not the Mexicans.

Through the Spanish woman’s translation, the official told Cahana that in order to photograph the Americans by the wall, she needed written permits from U.S. and Mexican authorities. Cahana asked him if he meant CBP. “Yes,” he told her.

At that point, Cahana had gone hours without food or adequate sleep. She couldn’t tell if the man was describing some official policy or just offering his opinion.

At 9:10 a.m., Cahana flew out of Mexico City. When she landed in Detroit hours later, she again ran her passport through the check-in machine — again, it returned an image of her face with a giant X on it. After two airport officials tried and failed to scan her passport, Cahana was taken to another back room, where two plainclothes officials, who said they were from Homeland Security, arrived to question her. The officials, a man and a woman, were looking at a computer as they asked Cahana questions about her interactions with Mexican authorities on the border. The officials specifically asked about “the day after Christmas.”

“He kept prodding at that,” Cahana recalled. Somehow, staring at their computer, the officials seemed to know the date and place where her passport had been photographed.

Remember this, Cahana told herself, this is significant.

Cahana left the airport with plans to return to her work. On January 24, she flew to Guatemala, hoping that if she crossed the Mexico-Guatemala border by land, she might not have the same troubles that she experienced at the airport in Mexico City. Cahana arrived in Guatemala without any issues, but when she presented herself at the port of entry to Mexico two days later, she was denied, told that there was a “migration alert” on her passport.

A migrant stands on the border fence before jumping to get to San Diego, Calif., from Tijuana, Mexico, on Dec. 28, 2018.

Photo: Daniel Ochoa de Olza/AP

A Pattern of Harassment

Cahana was not alone. From November 25 — the first time CBP used tear gas to repel members of the migrant caravan from the border — through the New Year’s incident, tensions on the border had been mounting. Along the way, U.S. border enforcement came to see members of the press and immigrant rights advocates as part of the problem and took a series of steps in response.

On December 2, Guillermo Arias, a Mexican photojournalist with Agence France-Presse with years of experience covering the Tijuana area, headed to a canyon along the border to shoot photos of a family looking to cross. He wasn’t the only one.

Journalists from around the globe had descended to document the families seeking to cross the border and present themselves to the Border Patrol for asylum. The international media attention that came with them was new, both for local press and for local enforcement. In years past, Arias told The Intercept, Border Patrol agents alone in the field, with nobody watching, could turn away migrants who made it onto U.S. soil without having to process them.

“When you have media, you can’t do that,” Arias said.

Turning away asylum-seekers is against the law. On December 1, photographer Fabio Bucciarelli and videographer Francesca Tosarelli, both Italian citizens, captured video that appeared to show agents doing just that.

The day after the Italians shot the footage, Arias sensed a change at the border. That was the first day that Border Patrol agents “got really aggressive with us,” Arias said, yelling at journalists and routinely taking photos of them.

Carol Guzy, a four-time Pulitzer Prize winner, also recalled the shift on December 2. “The agents were there, and they said women and children could come over, but not men. So a ton of women and children went over the border,” Guzy told The Intercept. “Afterwards, they came down to the fence, to the journalists that were standing on the Mexican side, with a camera, filming us all, basically yelling at us, saying we were the reason, we made these people climb that fence and we’re endangering children, and then all the while filming us.”

“It was so uncalled for and it was so ridiculous,” she said. Guzy, who was pulled into secondary screening in San Diego when she left Mexico later that month, added, “I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s a flag on my passport — that gives me the creeps that now they have a picture of all of us standing there. They must’ve done something with it.”

A week after the Border Patrol’s meltdown, tensions escalated even further. A video Bucciarelli and Tosarelli shot that day and shared with The Intercept shows a Border Patrol agent addressing members of the press through the border fence. “My agents say that some of you are aiding and abetting these people to enter the United States illegally, OK?” the agent, identified on his name patch as S. Gisler, told the press, informing them that they could be charged with a misdemeanor or a felony.

A journalist off-camera can be heard telling the agent that the accusations weren’t true.

“I’m just saying that if you come to the United States, we could conceivably get [an] arrest warrant for whoever was doing that, and if you ever come to the United States, we just charge you with that,” Gisler replied. “I don’t know if they’d actually prosecute you for it or not.” As he walked away, Gisler advised the press to let the migrants “just do what they’re gonna do,” and added, “some people say that reporters are helping them climb the fence.”

Video: Francesca Tosarelli

Four days later, Arias was back at the wall, shooting photos of migrants crossing the border to turn themselves in for asylum. As he returned to his vehicle, Arias was approached by a Mexican police officer. The officer said he was with Unidad de Enlace Internacional, a municipal Mexican police unit that works closely with its law enforcement counterparts on the northern side of the border.

With a decade of experience in Tijuana, including years covering the narco violence there, Arias was familiar with the unit and their relationship to the Americans. “These are the guys they call,” he said.

According to Arias, the officer told him that the unit was responding to a “suspicious activity” call from the Americans. Arias noticed the officer was holding a fistful of foreign journalists’ passports, Arias recalled. The two men argued about the law for about 15 minutes, with the officer claiming that the journalists did not have the credentials to shoot there, and Arias responding that the officer was trying to enforce laws that were not within his jurisdiction.

Arias was eventually allowed to leave. Two days later, the Border Patrol’s San Diego sector released a statement reporting that on December 13, surveillance footage had captured video of migrants illegally crossing the border “as photographers and media outlets filmed and, apparently, encouraged the group to cross illegally.”

The statement went on to claim that among more than 20 migrants were individuals “carrying professional-grade recording equipment, believed to be associated with the press.” It added that “agents reported hearing someone tell the group to climb over the [border] barrier,” and that camerapeople climbed to the top of the barrier as they crossed in “what appeared to be a staged event to capture the illegal crossing on video.” The Intercept requested to see the Border Patrol’s footage, but CBP did not provide it.

Cahana’s passport — along with the passports of the three other photojournalists she was working alongside — was photographed by Mexican police officers two weeks after the statement was issued. The municipal police department in Tijuana did not respond to a request for comment on its officers’ relationship to the press and U.S. law enforcement, but according to Arias, “They were pretty obsessed with the foreign journalists.”

On New Year’s Eve, hours before the tear gas was launched, the core group of foreign photojournalists documenting crossings over the international divide was back at the wall. It was dark and rainy. On the northern side of the border, four Border Patrol agents stood watch. Three were dressed in tactical kits. One shined a strobing flashlight at the journalists, while the other filmed them.

As shown on video footage provided to The Intercept, the agents accused the photographers of bringing migrant children out in the rain, so they could take photos of them attempting to cross the border. One agent turned his attention to a photographer with an umbrella. “That’s a man right there,” he said. “Yeah, I like that. That’s a fucking man right there. Yeah, the kids over there — who gives a fuck, right?”

A second agent added, “The reporters, they bring these people down so they can stand in the rain, so you guys can make a couple bucks. Shame on you, man. Shame on you. That should be the story. That’s the real story, how you guys are taking advantage of these poor people.”

“You guys are going to the shelters and telling them to come over here,” an agent said. “This is not happening naturally. You guys are enticing these people to come over here. You know it.”

According to Emilio Fraile, a Spanish freelance photojournalist, the agents’ comments at one point turned from condescending and accusatory to threatening. Fraile said he was focusing on shooting photos of a family preparing to cross when a fellow photojournalist told him, “They’re saying your name.”

Fraile didn’t believe it until he heard it for himself. “Where is Emilio?” the agents called out. “Where is Emilio?”

“They said it two or three more times,” Fraile told The Intercept in Spanish. “It was like, Fuck. Why do these people know my name?”

Fraile had not passed through a U.S. port or given his name to any agents on the line. The agents likely wanted the photographers to move back from the wall, Fraile said. “But of course, to a civilian, it’s quite a frightening gesture, right? To know your name, the American police, knowing who the president is in the United States.”

Left/Top: Honduran asylum-seekers try to jump the border wall from Tijuana on Jan. 1, 2019. Right/Bottom: Honduran asylum-seekers hide alongside the border wall to avoid being detected before attempting to cross on Dec. 30, 2018. Photos: Santi Palacios

Mining for Intelligence

On January 3, Fraile and two other Spanish freelance photojournalists, Santi Palacios, and Daniel Ochoa de Olza, a longtime AP contributor whose coverage of the New Year’s tear gassing was shared around the world, were approached by Mexican police.

Like Cahana and the others, the Spaniards’ passports were photographed. Palacios asked the officers why they were taking photos. It “was because the ‘Americans’ were asking them to do so,” Palacios told The Intercept. “They wanted to know who we were.”

“I asked if they send them to the police on the other side, and the officer said yes,” Palacios said.

According to Palacios, the officers then told the journalists that they couldn’t be in the area because they were on Mexican tourist visas and that if they saw them again, they would take them to the police station. Palacios added: “I also asked them if this was because of the collaborative police team that works on both sides of the border. They said yes, that they do work together and share info.”

Fraile, who also heard the exchange, added, “We were really surprised that the Mexican police told us they shared the information with the U.S. police.”

As the Los Angeles Times reported last week, Ochoa de Olza, who was with the other two Spaniards, was denied re-entry into Tijuana from San Diego in late January. Thus far, of the seven photojournalists known to have had their passports photographed by Mexican law enforcement, two have attempted re-entry into Mexico: Cahana and Ochoa de Olza. Both have been denied.

Days after their passports were photographed, Fraile and a colleague headed to the U.S. for a shopping trip via the San Ysidro port of entry. The two were directed to secondary screening, Fraile said. “They wouldn’t let us talk to each other,” he explained. “We were each taken to separate rooms where they interviewed us.” According to Fraile, the U.S. officials’ questions focused on the mood in Tijuana among participants in the caravan, and the activities of American activists there.

“He was asking us if there was any North American, anyone from the United States, collaborating with the migrants to help them cross the border,” Fraile said.

The Intercept interviewed the three other photojournalists who were with Cahana the night their passports were photographed — a week before the Spaniards’ encounter — and who similarly spent much of late December near the wall in Tijuana. Each described how, in the weeks that followed, they, too, were pulled into secondary screening by U.S. law enforcement as they returned to the U.S.

Aldo Ivan, 18, from Guatemala, and Griselda, 22, from Honduras, embrace on top of a cargo truck heading north toward Guadalajara on Nov. 12, 2018, where they would stay overnight at a temporary migrant shelter set up by the Mexican government.

Photo: Mark Abramson

Mark Abramson, a freelancer whose December work in Tijuana was also featured in the New York Times, was pulled into secondary screening at the El Chaparral port of entry as he returned to the U.S. on January 5. It was approximately 3 a.m., Abramson told The Intercept, when he approached the port on foot. “I had a feeling that it would happen,” Abramson said. “Because I knew that people were being stopped.”

The moment he arrived at the port, he was taken to a lobby in the secondary screening area. CBP officials told Abramson to sit and put his phone down, as they began going through his backpack and notes. Abramson explained that he was a photojournalist. A plainclothes agent then led him to a windowless room, illuminated with florescent light. With Abramson’s phone and belongings now in a separate room, the agent began a 30-minute interview.

The conversation was cordial, Abramson said, but the agent “was mining for intelligence.” The agent first focused on the leadership of the caravan. Abramson reiterated that he was a photojournalist, and that he, too, was interested in those sorts of questions. “I don’t know much,” he recalled saying. “I just know that the people are suffering and they’re definitely running from something, and my job is just to make as powerful a picture as I can of the scenes.”

The agent had a clear familiarity with the migrant camps on the other side of the border, Abramson said, and took a particular interest in how freelance photojournalists earn their money. The agent asked Abramson if he planned to come back to Mexico. Abramson, who had never been through secondary screening before, said that he’d like to, but he wanted to know if this was the kind of experience he could expect to repeat on a return visit. The agent assured him that it was just because Abramson was new to CBP. Abramson had his doubts.

The agent then asked if Abramson had any information about groups on the southern side of the border that might be helping migrants. “I knew he was referring to the gassing on New Year’s Eve,” Abramson said.

The events that night had been complicated and chaotic, and included not only migrants and journalists, but also American activists who had responded to the scene. In the aftermath of the gassing, the activists maintained that they had come to help, while others accused them of antagonizing law enforcement and placing migrants at risk. Abramson told the agent that he had seen medics present but left it at that.

“I didn’t want to feed him information — that’s not my job,” he said. “But they’re clearly mining for something.”

Photo: Go Nakamura

Bing Guan and Go Nakamura, both freelance photojournalists whose passports were photographed by Mexican police, described a similar experience. The two entered the San Ysidro port of entry by car early on the morning of December 29. Guan was driving and the vehicle was his. Just a few weeks before, he had crossed through the same port without any issues. This time, however, he was directed to secondary screening.

After roughly an hour of waiting, a pair of plainclothes officers separated the journalists for questioning. Guan was led to an interrogation room where one of the officers launched into a series of questions. Guan said the officer told him that his agency was looking for information on “instigators” on the border. He then presented Guan with a double-sided, multipage photo lineup.

“Maybe nine or 12 pictures per page of people who have been kind of around the caravan,” Guan recalled. “Including anti-migrant activists, as well activists who have been affiliated with the caravan, that have been kind of shepherding them through Mexico.”

Guan recognized three or four of the individuals included on the sheet. Two were anti-migrant activists, he said. A third, he believed, was associated with Pueblo Sin Fronteras, the immigrant rights organization most prominently associated with the migrant caravan. “They’re pretty much just blatantly telling us that they’re pumping us for information and trying to ID people around the caravan,” Guan said. “Which is weird and highly problematic.”

According to Guan, the images in CBP’s possession were a mix of what looked like travel document headshots, mugshots, and surveillance photos. Nakumara described being shown a similar set of photos. After being presented with the lineup, Guan was then asked to open up the images on his camera. He complied, reasoning that his images were too dark to be useful in identifying anyone.

After 2 1/2 hours, Guan and Nakamura were released.

Journalists who were in Tijuana in December, but did not have their passports photographed, have also experienced unusual scrutiny when returning to the U.S.

Manuel Rapalo, a freelancer with Al Jazeera, was among the journalists at the wall on New Year’s who Border Patrol accused of helping to facilitate migrant crossings. Since that night, Rapalo told The Intercept, he’s twice been pulled into secondary screening when flying back to the U.S. via Dulles International Airport in Washington, D.C. “They’re going through my bags, they’re going through my camera,” Rapalo said. “I’m used to that if I’m trying to enter Nicaragua, not trying to enter the United States.”

During the most recent screening, on January 18, Rapalo asked the officer who was detaining him why he keeps getting pulled aside. “The CBP officer told me it was likely due to the line of work I was in,” Rapalo said. Rapalo suspected that his New Year’s exchange with Border Patrol might have had something to do with what’s been happening. The first time he had been pulled into secondary, Rapalo said, the first question he was asked was, “Why did you have trouble at the border?”

“Honestly, there’s no reason he should have even known that I was at the border,” Rapalo said, noting that nothing in his travel documents, which reflected a flight from Mexico City, said anything about the border. “That was the first question.”

Targeting Humanitarian Groups

Multiple sources who went through secondary screening in the San Diego area described CBP’s focus on border-based activists and humanitarian groups, as well as officials’ efforts to access personal electronics.

Sindbad Rumney Guggenheim, an independent documentary filmmaker who spent two months with the caravan, was sent to secondary screening in the last week of December and the first week of January. During his second encounter, he was questioned about the New Year’s gassing and whether he was an activist. U.S. officials asked him to unlock his phone, which he did, and then they disappeared with the device for approximately 15 minutes.

“For all I know, maybe they cloned it,” Guggenheim said, adding that one of the women who questioned him wrote down his phone’s IMEI number. “They really took everything,” he said. “There was no privacy at that point that mattered.”

At least two volunteers with Border Angels, a humanitarian group that leaves water for migrants in the California desert, have been subjected to secondary CBP screening in the last two months. Volunteer Hugo Castro told The Intercept that he was detained by the agency for more than five hours on December 20. James Cordero, meanwhile, said he was first sent to secondary on Christmas Eve, when he was bringing a load of toys to children at a Tijuana shelter where many of the migrants who had participated in the caravan were staying.

Cordero described being taken into an interrogation room at El Chaparral, where a pair of plainclothes officers pressed him for information on who ran the shelter and what the mood was like there. Cordero, too, was then presented with a series of photographs.

“Some were like mugshots, some were like real bad security camera photos, and then some were photos from people’s driver’s licenses,” he recalled.

By the time he got to the last page, Cordero recognized three members of Pueblo Sin Fronteras — depicted in driver’s license photos — and a friend who organized rallies on the U.S. side of the border on issues like Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA.

Alex Mensing was one of the Pueblo Sin Fronteras volunteers included in CBP’s photo lineup. A longtime organizer with the group, Mensing told The Intercept that he began noticing an uptick in pressure from the border enforcement agency in the spring of 2018, during the first migrant caravan that drew Trump’s ire. “I started getting sent to secondary in May 2018,” Mensing said. That was around the same time that migrants taken into U.S. custody started reporting that they were being asked about Pueblo Sin Fronteras. Since then, Mensing estimates that he’s been pulled into the heightened screening process between 15 and 20 times.

When the most recent caravan arrived in Tijuana in November, giving Trump a pretext to deploy thousands of troops to the border, Mensing got a call from a fellow Pueblo Sin Fronteras volunteer who had been taken into secondary screening. “The very first thing they asked them was, Who is Alex Mensing?” he recalled. According to Mensing, the officer told the volunteer that while the agency did not suspect that they were involved in human trafficking, “that doesn’t mean that your friends aren’t.”

Left/Top: Honduran sisters Yeyi Cambell, 11, and Jeyri Cambell, 7, play near the U.S.-Mexico border crossing at El Chaparral, Tijuana, on Nov. 22, 2018. Right/Bottom: Honduran migrant Wilmer Rosa, 32, looks for a place to unfurl his blanket at a temporary migrant shelter in Tijuana.Photos: Bing Guan

The pressure since then has been intense, Mensing said, with every Pueblo Sin Fronteras volunteer who has crossed the border since December — six people in total — having been sent to secondary screening.

Jeff Valenzuela, a Pueblo Sin Fronteras volunteer living in Tijuana, told The Intercept that he has been sent to secondary screening a half-dozen times since late December.

On Christmas Day, Valenzuela approached the El Chapparal entry on foot. After waiting for two hours, two plainclothes officers, both women, escorted him to an interview room where they asked a series of general questions about the caravan and the condition of the shelters in Tijuana. During the questioning, Valenzuela was told that the officers needed to look through his phone. “You can hold it the whole time,” he recalled being told. “It’s standard procedure to make sure you don’t have child pornography.” It was either that, Valenzuela was told, or the phone could be seized and sent to a second location.

Valenzuela did as he was requested, allowing the officers to watch as he scrolled through his photos for approximately 30 seconds. He was released roughly 2 1/2 hours after he arrived.

Two days later, Valenzuela again came to the border, this time by car. He was on his way to visit his family in Los Angeles. A pair of officers approached his vehicle and told him to get out and put his hands behind his back. As one of the officers reached for a pair of handcuffs, Valenzuela was told that he was not being placed under arrest. Again, he was told, “this is just standard procedure.” Valenzuela was led to a “discreet door” nearby, where he stepped into what he described as a “jail-like booking room.”

Valenzuela’s belongings were confiscated, and he was walked to a steel bench.

Valenzuela said the officers then shackled his ankle to the bench. “Meanwhile, they’re telling me that I’m not being arrested,” he said. According to Valenzuela, he spent more than four hours shackled to the bench before two plainclothes officers arrived and took him to another interview room. The questions were much the same as the last time, Valenzuela said. This time, however, the officers told him to unlock his phone. When Valenzuela questioned whether he could really be compelled to do that, he was presented with a document, which said that his phone had been “detained for further examination, which may include copying.”

“At that point, I had been there for about five hours,” Valenzuela said. He gave in and unlocked the phone. He now regrets the decision. When the phone was returned some 40 minutes to an hour later, Valenzuela discovered that his email had been refreshed, and it seemed that most of the apps on the device had been accessed. Valenzuela was pulled into secondary screening four more times in the weeks that followed and, on January 25, was again shackled to the steel bench in the nondescript processing room.

Now, Valenzuela told The Intercept, he gives himself several hours of lead time before heading into the U.S., makes sure multiple people know he’s crossing, and leaves his phone behind.

David Abud, another Pueblo Sin Fronteras volunteer, has been sent to secondary screening twice since December, with his longest interview taking place at Los Angeles International Airport in early January, following a trip to visit friends and family in Mexico and Honduras. “It’s an escalation of the attack on asylum rights,” Abud told The Intercept. He described it as a Trump administration experiment, one that began by targeting a highly marginalized population — noncitizen migrants — and is steadily expanding outward.

“They’re threatened first by the migrants, and then they’re threatened also by the people that are supporting them,” he said. “I think it just sets a really dangerous precedent if there isn’t more pushback against this.”

Photo: Go Nakamura

Shutting Down Coverage

While CBP has said that it did not flag Nora Phillips and Erika Pinheiro, the Al Otro Lado attorneys who were denied entry into Mexico last week, the lawyers are not taking the claim at face value.

Pinheiro suspected that U.S. officials called counterparts in Mexico and urged them to flag the lawyers themselves. Roughly a year ago, she said, Al Otro Lado learned that CBP had asked a Mexican official to inquire about the immigration status of one of the organization’s lawyers. “This isn’t the first time they’ve looked into our immigration status,” Pinheiro said in an interview from Los Angeles.

The lawyers are already moving to launch inquiries in Congress, in the Mexican government, and with Interpol. “I think we’ll get to the bottom of it,” Pinheiro said. “In the meantime, I’m stuck here.” For an American attorney residing in Mexico, who represents 43 parents who were deported without their children during the Trump administration’s family separation campaign, an inability to cross borders is no small matter.

Join Our Newsletter

Original reporting. Fearless journalism. Delivered to you.

All of the individuals who spoke to The Intercept about the disruptions of their work along the border described a profound impact on their lives. Valenzuela, the Pueblo Sin Fronteras volunteer living in Tijuana, has missed time with his family in California because of his repeated referrals to secondary screening, and he now worries about his ability to commute to a new job in San Diego. For the many photojournalists who worked in the Tijuana area in late 2018, particularly the freelancers who lack the institutional support of a news organization, there is deep concern about future trips.

For now, Kitra Cahana remains in Guatemala. She continues to shoot photos, documenting the families moving north through the country, though she can only follow them so far. She’s spoken to several lawyers and press advocacy organizations, and she hopes — though she does not necessarily expect — that something will give in her case. Keith Chu, a spokesperson for Wyden, told The Intercept that his office “has been in contact with Ms. Cahana, and is in the process of investigating her case.”

“It seems like both governments are pointing the finger at the other government,” Cahana said of the U.S. and Mexico. “Maybe that’s how they want it.”

Cahana feels an obligation to determine exactly what happened in her case and why, both for the sake of her colleagues — especially the freelancers now worried about whether a ticket to the border is worth the risk — and for the issues they cover. “There’s a lot of opaqueness around migration issues,” Cahana said. “It’s our duty as journalists to shed light and bring about some clarity so that the public can make more informed decisions.”

“If we can’t do that, then I think society at large suffers.”