Above Photo: From Stumblingandmumbling.typepad.com

I welcome Professor Sir Angus Deaton’s report into inequality. I especially like its emphasis (pdf) upon the causes of inequality:

To understand whether inequality is a problem, we need to understand the sources of inequality, views of what is fair and the implications of inequality as well as the levels of inequality. Are present levels of inequalities due to well-deserved rewards or to unfair bargaining power, regulatory failure or political capture?

I fear, however, that there might be something missing here – the impact that inequality has upon economic performance.

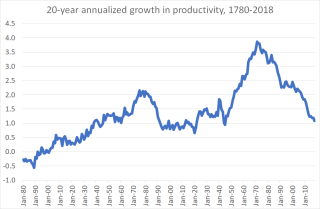

My chart shows the point. It shows the 20-year annualized rate of growth in GDP per worker-hour. It’s clear that this was much stronger during the relatively egalitarian period from 1945 to the mid-70s than it was before or since, when inequality was higher.

This might, of course, be coincidence: maybe WWII caused both a backlog of investment and innovation which allowed a subsequent growth spurt and a desire for greater equality.

Or it might not. This is not the only evidence for the possibility that inequality is bad for growth. Roland Benabou gave the example (pdf) of how egalitarian South Korea has done much better than the unequal Philippines. And IMF researchers have found (pdf) a “strong negative relation” between inequality and the rate and duration of subsequent growth spells across 153 countries between 1960 and 2010.

Correlations, of course, are only suggestive. They pose the question: what is the mechanism whereby inequality might reduce growth? Here are eight possibilities:

1. Inequality encourages the rich to invest not innovation but in what Sam Bowles calls “guard labour” (pdf) – means of entrenching their privilege and power. This might involve restrictive copyright laws, ways of overseeing and controlling workers, or the corporate rent-seeking and lobbying that has led to what Brink Lindsey and Steven Teles call the “captured economy.” An especially costly form of this rent-seeking was banks’ lobbying for a “too big to fail” subsidy. This encouraged over-expansion of the banking system and the subsequent crisis, which has had a massively adverse effect upon economic growth.

2. Unequal corporate hierarchies – what Jeffrey Nielsen calls rank-based organizations – can demotivate junior employees. One study of Italian football teams, for example, has found that “high pay dispersion has a detrimental impact on team performance.” That’s consistent with a study of Bundesliga and NBA teams by Benno Torgler and colleagues which found that “positional concerns and envy reduce individual performance.”

3. “Economic inequality leads to less trust” say (pdf) Eric Uslaner and Mitchell Brown. And we’ve good evidence that less trust means less growth. One reason for this is simply that if people don’t trust each other they’ll not enter into transactions where there’s a risk of them being ripped off.

4. Inequality can prevent productivity-enhancing changes, as Sam Bowles has described. We have good evidence that coops can be more efficient than hierarchical ones, but the spread of them is prevented by credit constraints. Poverty reduces education levels by making it impossible to afford books, or encouraging bright but poor students to leave earlier than they should, and women and BAME people might avoid careers for which they are otherwise well-suited because of a lack of role models.

5. Inequality can cause the rich to be fearful of future redistribution or nationalization, which will make them loath to invest. National Grid is belly-aching, maybe rightly, that Labour’s plan to nationalize it will delay investment. But it should instead ask: why is Labour proposing such a thing, and why is it popular?

6. Inequalities of power – in the sense of workers’ voices being less heard than they were in the post-war period and trades unions becoming less powerful – have allowed governments to abandon the aim of truly full employment and given firms more ability to boost profits by suppressing wages and conditions. That has disincentivized investments in labour-saving technologies.

7. The high-powered incentives that generate inequality within companies can backfire. As Benabou and Tirole have shown (pdf), they encourage bosses to hit measured targets and neglect less measurable things that are nevertheless important for a firm’s success such as a healthy corporate culture. Or they might crowd out intrinsic motivations such as professional ethics. Big bank bonuses, for example, encouraged mis-selling and rigging markets rather than productive activities.

8. High management pay can entrench what Joel Mokyr calls the “forces of conservatism” which are antagonistic to technical progress. Reaping the full benefits of new technologies often requires organizational change. But why bother investing in this if you are doing very nicely thanks to the increased (pdf) market power of your firm? And if you have, or hope to have, a big salary from a corporate bureaucracy why should you set up a new company?

My point here is that what matters is not so much the level of inequality as the effect it has. And it might well be a pernicious one. If inequality has contributed to weaker growth, then it is very likely to have contributed to the rise of populism and to Brexit and the divisions with which both are associated. In this way, inequality does political damage too.

From this perspective, pointing out that the Gini coefficient has been flat for years (which is true if we ignore housing costs) is like saying that because the bus has stopped moving we need not care about the man who has been run over by it. It misses the main point.