Above photo: Children playing in Crawfish Rock, Honduras, where a ZEDE charter city is forming. Dassaev Aguilar.

The charter of Honduras’s first Economic Development and Employment Zone (ZEDE) reveals implications of the new enclave model for popular sovereignty.

“It’s almost like an insult that this is happening to us now, after so much sacrifice to develop the community to the point it’s at today,” Venessa Cardenas explains, in Crawfish Rock, Roatán, as she remembers her grandmother who passed away last May at 90 years old. “She was the one who fought for us to have the road, the school, water, all of the basic projects… the government has never given us anything that we didn’t fight for. She gave everything for this community. She’s the reason me and my family are so firm.”

Venessa’s community is located between two tourism projects—Pristine Bay and Palmetto Bay—on the Honduran island of Roatán, where she serves as vice-president of the patronato, the community governing council. Her family has been in Crawfish Rock for five generations and seen different kinds of tourism investment come to the island over the years. But recently, Crawfish residents learned that their municipality was ground zero for a new enclave model that has allowed a group of investors from the Washington DC-based firm NeWay Capital to establish an independent governance system as an experiment with privatized jurisdictions.

Hondurans are facing a sudden onslaught of these new jurisdictions, Economic Development and Employment Zones (ZEDEs), which international promoters refer to as “charter cities,” “startup cities,” or “free private cities.” U.S. economist Paul Romer, currently disassociated from the project, and Honduran politicians from the National Party proposed the zones shortly after the 2009 military coup, which made the country a ripe location for experimentation with extreme neoliberal policies. The 2013 ZEDE law provided unprecedented legislative, administrative, judicial, and financial autonomy to investors for a wide range of territorial ventures, including urban development and resource extraction.

The legal framework of the ZEDE caught the attention of libertarian and free-market venture capitalists who sought opportunities to create a global market of private governments. However, internal disagreements and public controversies over government corruption, drug trafficking, and electoral fraud slowed the project. Government promises of fantastical new city projects that would build a “Honduran Hong Kong” appeared to be smoke and mirrors, as behind the scenes attempts to establish ZEDEs were largely kept secret from the public. Since May 2020, two ZEDEs have been officially launched: the “Honduras Próspera” ZEDE (PZ) on Roatán where Crawfish Rock is located, and the “Ciudad Morazán” ZEDE in the industrial town of Choloma. The founders of Próspera have referenced a third site in La Ceiba, and are also considering Cuyamel, Puerto Cortés, Puerto Castilla, and Amapala in the southern region as additional future hubs.

According to Crawfish residents, developers did not present the Próspera project to them as a ZEDE. Once it was revealed to be a ZEDE, the project provoked national debate over whether the ZEDEs represented a privatization of Honduran sovereignty or were simply a new form of democratic local government. The constitutional charter of Honduras’ first ZEDE, Próspera, along with its extensive code of rules, was made public at the official site of the Published Internal Rules of the Próspera ZEDE. While the ZEDE law, passed in 2013, has been analyzed elsewhere, here we will discuss the form of government this group of investors has established by way of the Próspera charter within the parameters of autonomy provided to them in the ZEDE law. Implications of the Próspera governance system include an erosion of popular sovereignty, a discriminatory model for most Hondurans, and a misleading and faulty internal democracy.

Governance Structure and Decision Making in the Próspera ZEDE

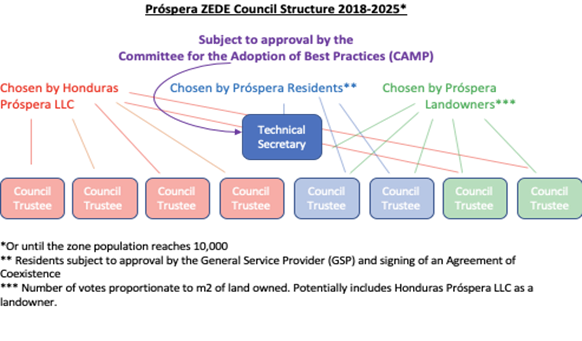

The structure of the Próspera ZEDE, as outlined in the reformed constitutional charter approved on July 26, 2019, is a highly corporatized model of governance with minimal opportunities for participation. A primary authority, the Technical Secretary (TS), governs the ZEDE alongside other key bodies, including the “Promoter and Organizer,” a private company registered in Delaware called Honduras Próspera LLC, and the Council of Trustees, referred to as “the Council” in this article. The Council oversees the PZ Trust and is the PZ’s primary governing body, with nine voting members including the TS and NeWay Capital and Honduras Próspera LLC CEO Erick Brimen as Secretary. Other Trustees include Oliver Porter, founder of the Sandy Springs model, Jeanette Doran, President of the North Carolina Institute for Constitutional Law, and Gabriel Delgado, a tech and cryptocurrency entrepreneur associated with the Francisco Marroquin University in Guatemala. They serve seven-year terms with no term limits. Próspera also has two Council Observers: Rodrigo Quercia, CEO of Brazilian real estate, retail, and agribusiness conglomerate Grupo Solpanamby, and Tom Murcott, who played a lead role in attracting investors and residents to the Songdo IDB in the Incheon smart city in South Korea.

The charter allows Próspera to operate as a corporation that can contract with private or public actors. One primary contract is with the General Service Provider (GSP), a private entity to which the provision of services such as water and electricity, education, and healthcare as well as other elements of local governance, are outsourced. The GSP can collect fees in exchange for services and pays a determined royalty to the Council.

Any semblance of local democracy in the Próspera charter is undermined by the power of the Committee for the Adoption of Best Practices (CAMP) over each ZEDE government. The CAMP is a 12 to 21-person body that was appointed by President Hernández and ratified by Congress in 2014. It is subject to little oversight and fills its own vacancies. According to the most recent publicly available information, its members include nine U.S. citizens and only four Hondurans. The CAMP must approve the ZEDE’s choice of Technical Secretary as well as the zone’s internal rules and norms and therefore holds the power to override local decisions.

Even so, limits to internal democratic decision-making in the PZ are also significant. Honduras Próspera LLC selects four of the nine Council Trustees. Although PZ “Residents,” those who are approved and fulfill a list of criteria explained below, elect a majority of decision-makers—four Council Trustees plus the Technical Secretary—further stipulations chip away at even this partial representation. Until August 2025, or when PZ reaches a population of 10,000 residents, two of the four Trustees subject to Resident vote will be elected by land-owning Residents only. Land-owners will exercise one vote per square meter of land owned and registered in the ZEDE’s independent land registry. After this point, the Council will determine the continuation of vote-by-land ownership. By then, the PZ will have likely entered many contracts that would be difficult to reverse, as the passage of any rule that terminates an existing contract will require the vote of two thirds of the Council.

Only after Natural Residents reaches 10,000 do Residents have the ability to repeal existing rules with a two-thirds vote, and new rules by a simple majority, but only within 7 days of the Rule’s passing.

Resident Status and Likelihood of Exclusion

Despite a rhetoric of freedom and choice, ZEDE residency is likely to be restricted, even among Honduran citizens. New residents must be approved by Próspera’s private General Service Provider (GSP) using criteria including available space in the ZEDE, ability for the ZEDE to manage growth, the reputation and social harmony of Próspera, the applicant’s criminal record, and the ability to pay applicable taxes and fees. These include an annual Resident fee of $260 for Honduran citizens and $1,300 for foreigners, an annual e-Gov license fee of $130 to access Próspera’s digital governance platforms, and a general liability insurance policy sold by the GSP at an annual premium of $260 maximum.

Through vague language such as “reputation and social harmony,” it is highly possible the GSP will use its discretion to achieve political and ideological cohesion in Próspera through exclusion. In 2019, Titus Gebel, a former member of the ZEDE of North Bay Council and a chief architect of the Próspera legal system, told a German media outlet that the “ZEDE will reserve the right not to admit, for example: serious criminals, communists and Islamists.”

Such cohesion-by-design is also reinforced by an “Agreement of Coexistence,” a legally binding contract that residents must sign with the PZ government. Zone administrators tout this Agreement as a codification of the “social contract” assumed between citizens and governments in the modern nation-state. This time, citizens (Residents) can sue their governments for breach of contract. But what the Agreement does in effect is reduce, if not eliminate, the possibility for contentious politics. In Section 1(b), Residents agree to “such delegation of popular sovereignty as is necessary to sustain the power and authority held in trust by the PZ” as well as to “comply with the provisions of the PZ Promoter and Organizer’s master plan common interest community declaration,” to be enacted on all land registered within the PZ. In exchange, Residents are promised “legal stability” for individuals and property.

The Agreement also seems to preclude the possibility of social welfare. Residents must commit to “self-responsibility,” meaning the ability to meet the financial obligations to the PZ without relying on subsidies from the PZ government. Breach of this Agreement can result in revocation of residency. New Residents are also subject to a probationary period of one year, during which the PZ can terminate their Residency without cause. Terminated Residents have 180 days to vacate the zone before being evicted.

The cost, requirements, and subjective selection of Residency make it likely that some Hondurans who work in the zone will be relegated to a non-Resident underclass.

Justice System

The Agreement of Coexistence also upholds the Resident Bill of Rights, which emphasizes individual freedoms and protects private property. This individualist approach to subjective rights contrasts with current international attempts to increase protection of collective interests and the commons. PZ’s rights scheme also breaks with social rights, such as certain labor rights, health, maternity leave, and the people’s right to insurrection, that crystallized in the 1982 Honduran Constitution. Even though all ZEDEs are ordered to fulfill the principles of human rights in the Honduran Constitution, it is legally unclear how the latter can coexist with the property-based regime ingrained in the Próspera Charter.

PZ’s adjudicative system is designed to integrate common law as an alternative to the country’s civil legal system. It is made up of the Próspera Court and the Próspera Arbitration Center (PAC). The Próspera Court is a judicial body that holds exclusive jurisdiction in PZ but is limited to criminal matters and those related to children and adolescents. The CAMP proposes members of the Próspera Court, who are then appointed by the Honduran Judiciary Council, but as of 2020 there is no information available about the judges who will serve on the Próspera Court.

The PAC is a dispute settlement mechanism that may eventually provide services to various ZEDEs, which the Agreement of Coexistence obliges Residents to use for all disputes except those specifically delegated to the Court. Eight non-Honduran arbiters and one Honduran arbitral officer have already been appointed to the PAC by Próspera ZEDE. The three Senior Arbiters of the PAC are from the state of Arizona. It is also notable that the CEO and Secretary of the PAC, Humberto N. Macias, is also Deputy General Counsel for Honduras Próspera LLC. The PZ Court, the PAC, or any arbitration tribunal is also empowered to reform the Próspera Charter, subject to ratification by a simple majority of natural Residents through a referendum.

Individuals or local communities affected by the PZ’s activities may have restricted access to the PZ adjudicative system for several reasons. First, information regarding the PZ’s legal and adjudication system is neither clear nor easily accessible to the public. Adopting a new legal system might exclude Honduran lawyers who lack the means to adapt to a new common law practice. For example, Próspera has created a legal framework called “Roatán Common Law Code” that compiles a large set of norms on private law, including from U.S. common law. Second, it is unclear if the adjudicative system will be physically accessible and affordable. According to a PAC fee calculator, for a Próspera resident to file, for example, a labor related claim of $10,000 under standard arbitration procedures, the estimated fee would be $1,120 with $392 of that amount paid upon filing, and all fees recoverable as costs by the prevailing party. For Honduran Citizens (not Próspera Resident) this same proceedings would be $378 more expensive. Finally, communities affected by Próspera activity outside of its borders have limited mechanisms for accessing justice either through Honduran courts that have no jurisdiction over the PZ, or through the PZ judicial system.

Once the population of Próspera reaches 1,000 natural person Residents, those who are Residents of Próspera can file complaints through an Ombudsman appointed by the CAMP for violations of the Residents’ Bill of Rights. However, the Ombudsman is severely disincentivized to pursue complaints because it is personally financially liable if arbitrators determine the proceedings to have been “an abuse of process or otherwise frivolous.”

According to Cardenas, Próspera representatives have done little to explain Resident status or the governance structure to the Crawfish population. To the contrary, local residents understand that the municipal government no longer holds jurisdiction over the 58 acres now incorporated into the ZEDE model. The land has allegedly been transferred from the municipal registry to an independent Próspera ZEDE land registry.

Land dispossession is an essential concern of communities. The ZEDE law gives the Honduran state the ability to expropriate land for the development or the expansion of each zone, which must be compensated, but cannot be challenged by landholders. According to the Permit Registrar of PZ, investors are even able to apply for an Indigenous Impact Permit when a project poses a “substantial risk of involuntary displacement of indigenous populations groups.” The permit lasts for six months and costs $200.

In an audio file sent to the community, NeWay CEO Erick Brimen has claimed, as has the Honduran government, that Próspera holds no intention to expropriate Hondurans of their land: “[We] have not taking any land, have not forced any transaction, and never will. Never will. You have my word on that. You don’t have to take my word, but you have it.”

Próspera is now building and marketing luxury homes on the property. According to a Próspera survey, those interested in inhabiting the zone can seemingly reserve a residence with a refundable $5,000 reservation fee. Bulldog Security contractors have begun securing the PZ area. Additionally, the Próspera ZEDE has begun admitting Residents and aims to attract mobile tech workers, entrepreneurs, and investors by offering an expansive menu of regulatory options.

But Cardenas asserts that the primary struggle right now is to get Congress to repeal the ZEDE law.

“I don’t care what anyone says about expropriation. What I care about is what’s written in the law passed by Congress. That’s what matters…” she says. “They might say ‘we won’t expropriate you,’ but maybe the next person will be different. Maybe other investors will need Crawfish Rock or another community, so the risk is very high for Hondurans.”

Andrea Nuila Herrmannsdorfer is an international lawyer and PhD candidate in law at the University of Bremen. Her doctoral research focuses on the legal implications of zones such as ZEDE in the future of public international law.

Beth Geglia is a researcher and PhD candidate in anthropology at American University. Her doctoral research focuses on ZEDE development, governance, and land struggles in Honduras.