Above Photo: Collage of UC Global surveillance photos of Assange made for CIA inside Ecuador embassy. Photos include Assange being examined by a doctor and the “decoy Dad” arriving at embassy. Cathy Vogan.

U.S. prosecutors have five times misled two British courts on key points about Julian Assange’s health as it attempts to overturn a ruling against extraditing him to the United States.

The United States appeal against a British judge’s decision not to extradite imprisoned WikiLeaks publisher Julian Assange begins at the High Court in London on Wednesday with prosecutors for the U.S. seeking to prove Assange is faking psychological disorders and urges to kill himself.

The U.S. wants the High Court to overturn the order of Magistrate Vanessa Baraitser on Jan. 4 not to extradite Assange to the U.S. — to face charges of espionage and conspiracy to commit computer intrusion — because of Assange’s high risk of suicide and the inhumane conditions of U.S. prisons.

The High Court on July 7 granted the U.S. leave to appeal that decision, but initially limited it to issues not related to Assange’s health. In an unusual move, the U.S. challenged those grounds for appeal.

On Aug. 11, a High Court judge reversed the same court’s earlier decision, allowing the U.S. to argue at this week’s hearing that Assange is a malingerer mentally fit to be extradited and that testimony that says otherwise should be thrown out.

An assessment of Assange’s mental state is now the key issue on whether he will be freed or sent to the United States.

The U.S. appears determined to win its appeal by any means necessary. But an examination of U.S. prosecutors’ and witness statements at the September 2020 extradition hearing and at the Aug. 11 hearing shows that the U.S. has misled the court, either deliberately or otherwise, on key points regarding Assange’s mental state.

There have been at least five instances of the U.S. misleading the courts about Assange’s mental health and suicidal tendencies:

- At the Aug. 11 hearing a U.S. prosecutor neglected a key Assange witness’ motivation for hiding the identity of Assange’s partner and their children in an effort to get key medical testimony thrown out;

- A prosecutor for the U.S. misrepresented two of its own expert’s testimony about Assange’s autism, falsely stating that they fully contradicted the defense;

- The U.S. lead prosecutor argued falsely in the September 2020 hearing that no razor blade was found in Assange’s cell at Belmarsh Prison;

- A U.S. expert witness incorrectly testified about the reason why Assange was moved into isolation at the prison in 2019;

- The lead prosecutor dismissed as “palpable nonsense” suggestions that Assange faced a threat of assassination, something which could affect his mental state.

Banging His Head on the Cell Wall

The U.S. is fighting to dismiss the testimony of Assange witness Michael Kopelman, emeritus professor of neuropsychiatry at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London.

Kopelman testified under oath at the September 2020 extradition hearing that Assange has had a history of clinical depression and said his risk of suicide would increase if extradition were about to happen.

“[Assange] has made various plans and undergone various preparations such as: he’s confessed to the Catholic priest who granted him absolution, he’s begun to draft farewell letters to his family and close friends, he’s drawn up a will,” he testified from the stand at Old Bailey. “It is the imminence of extradition and/or an actual extradition that will trigger the attempt, in my opinion.”

Kopelman cited a study showing that someone like Assange who is diagnosed with Asperger’s is nine times more likely to commit suicide.

In her judgement to bar extradition, Baraitser accepted Kopelman’s testimony and described how Assange was so distraught that he punched himself in the face, banged his head against his cell wall and repeatedly called a suicide hotline.

“Professor Kopelman considered that, if housed in conditions of segregation and solitary confinement, Mr. Assange’s mental health would deteriorate substantially resulting in persistently severe clinical depression and the severe exacerbation of his anxiety disorder, PTSD and suicidal ideas,” Baraitser wrote.

This is the man the U.S. is trying to portray as a malingerer and not suicidal.

James Lewis QC, the lead prosecutor for the U.S., sought to undermine Kopelman’s credibility during his oral testimony from the witness stand at Old Bailey on Sept. 22, 2020.

On cross examination Lewis questioned Kopelman’s credentials, saying he was not a forensic psychiatrist, who work in prisons. Kopelman retorted that he had spent time in many prisons and that even Lewis had once urgently called upon him for his expert testimony in an extradition case. That brought laughter in the courtroom, even from Baraitser.

To have Kopelman’s testimony thrown out, the U.S. will argue this week that he was not an impartial witness because he deceived the court by having concealed his knowledge of Assange’s two children with his partner and lawyer Stella Moris.

Kopelman failed to mention Moris or the children in his December 2019 preliminary submission to the court but did in his written testimony in August 2020, a month before Assange’s extradition hearing resumed. The U.S. knew about it as early as April 2020 in time for the September extradition hearing.

The U.S. argues that initially concealing the children misled the court because having small children makes it less likely Assange would take his life. This was based on Kopelman’s preliminary report in which he wrote that Assange told him his family kept him from killing himself.

In her judgement, Baraitser wrote:

“Professor Kopelman was aware that Mr. Assange’s children were a significant factor in the assessment of his risk of suicide, as Mr. Assange had told him in August 2019 ‘The only things stopping [me] from suicide were the ‘“small chance of success”’ in his case, and an obligation to his children.’”

Despite this, Baraitser’s judgement on Jan. 4 of this year showed that he was still highly likely to commit suicide.

Reason to Conceal the Children

Moris, and by extension Kopelman, hid her and the children’s identities in light of revelations that a Spanish security company working for the CIA had spied on Assange inside the Ecuadorian embassy in London, including on visits with his lawyers, doctors, Moris and their first child.

UC Global employees testified in a court case in Madrid against the company’s CEO (and later at Assange’s extradition hearing) that the CIA wanted to nab one of their baby’s diapers to prove Assange’s paternity through DNA testing.

Moris was forced to reveal the identity of the children in April 2020 when a bail application required information about with whom Assange would live if he were released. Moris had asked the court to keep that information sealed but Baraitser refused “in the interest of open justice.”

That same month Moris then publicly revealed to the Daily Mail and Australia’s 60 Minutes her relationship with Assange as well as alarming details of what had been happening to the family at the embassy.

Moris said she’d been worried that British tabloids would make her life hell if they found out she was the mother of Assange’s children.

Moris and Assange had been aware they were being filmed and tried to conceal their relationship. She lived elsewhere and had a “decoy dad” bring their infant son Gabriel to the embassy, pretending the child was his.

Moris was distressed when an embassy guard warned her the baby should not be brought back. It’s not clear what might have happened to the child if it were proven he was Assange’s son.

Ethical Obligation

Whether intentionally or not, U.S. prosecutors are misleading the court in wanting to throw out Kopelman’s testimony on this basis because he was actually fulfilling his ethical duty to protect Assange’s children by initially concealing their existence from the court.

Lissa Johnson, a clinical psychiatrist and Assange supporter, told Consortium News that “irrespective of whether they are acting as expert witnesses in legal proceedings, psychiatrists and psychologists remain bound by their ethical obligations to avoid causing harm (non-maleficence), including to third parties. Where a child is at risk, that child’s welfare is paramount.”

Baraitser, in her ruling against extraditing Assange on health grounds, acknowledged Kopelman had good reason to initially exclude mention of the children to protect Moris’ safety. Baraitser wrote:

“In my judgment, professor Kopelman’s decision to conceal [Assange and Moris’s] relationship was misleading and inappropriate in the context of his obligations to the court, but an understandable human response to Ms. Moris’s predicament. He explained that her relationship with Mr. Assange was not yet in the public domain and that she was very concerned about her privacy.

After their relationship became public, he had disclosed it in his August 2020 report. In fact, the court had become aware of the true position in April 2020, before it had read the medical evidence or heard evidence on this issue … In short, I found Professor Kopelman’s opinion to be impartial and dispassionate; I was given no reason to doubt his motives or the reliability of his evidence.”

During the Aug. 11 hearing in which the U.S. won its challenge to appeal Assange’s heath issues this week, Assange lawyer Edward Fitzgerald did not elaborate on the nature of “Ms. Moris’s predicament.” Had he done so, the High Court judges Lord Justice Holroyde and Mrs. Justice Farbey may have understood that Moris’ child was in danger.

It would have been arguable, and still is, that Kopelman’s “understandable human response” was his duty to protect a child’s safety. Holroyde will be on the bench with Lord Chief Justice Ian Duncan Burnett for this week’s hearing. (Burnett overturned an extradition order to the U.S. for activist Lauri Love in 2018 because of Love’s high risk of suicide. Kopelman also testified in that case.)

Twisting Testimony on Autism

Dr. Quinton Deeley, a senior lecturer in social behaviour and neurodevelopment at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience, King’s College London and consultant neuropsychiatrist in the National Autism Unit, also testified for Assange on Sept. 24, 2020 that he would be at “high risk” of suicide if extradited. Deeley said Assange’s Asperger’s syndrome and autism led to his “obsessive rumination” about suicide if he were sent to the United States.

Former British diplomat Craig Murray reported from the courtroom:

“Deeley, after overseeing the standard test and extensive consultation with Julian Assange and tracing of history, had made a clear diagnosis which encompassed Asperger’s. He described Julian as high-functioning autistic.”

Murray then recorded the reaction of the lead U.S. prosecutor:

“There followed the usual disgraceful display by James Lewis QC, attempting to pick apart the diagnosis trait by trait, and employing such tactics as ‘well, you are not looking me in the eye, so does that make you autistic?’”

Dr. Seena Fazel, professor of forensic psychiatry at the University of Oxford, followed on the stand the same day for the prosecution. Murray wrote:

“There was a great deal of common ground between Fazel and the defence psychiatrists, and I think it is fair to say that his major point was that Julian’s future medical state would depend greatly on the conditions he was held in with regard to isolation, and on hope or despair dependent on his future prospects.”

Consortium News reported that day that Fazel testified Assange exhibited autistic traits, but it was “not a clear-cut case.”

Even Nigel Blackwood, a forensic psychiatrist for the National Health Service and the lead prosecution medical expert, did not totally dismiss that Assange was suffering from autism, testifying “that any traits of autism were on the low end of the spectrum.”

In her judgement not to extradite Assange, Baraitser “noted that both Professor Kopelman and Professor Fazel had recorded autistic-like traits in Mr. Assange.”

“[Fazel] agreed with the view that Mr. Assange has some autistic-like traits,” Baraitser wrote.

Despite the evidence and this clear language in the lower court judgement, prosecutor Clair Dobbin at the Aug. 11 High Court hearing said, as Consortium News reported: “Neither Fazel nor Blackwood agreed that Assange was on the autistic spectrum.” Journalist Kevin Gosztola live tweeted, “Dobbin: Neither Fazel nor Blackwood agreed with diagnosis that Assange was on autistic spectrum.”

‘Disingenuous’

“It sounds as though Claire Dobbin is referring to whether Fazel issued a clear-cut diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder,” said Johnson. “With the words it’s ‘not a clear cut case’ Fazel essentially abstained on that count. It is disingenuous to frame this as disagreement with Kopelman, when both experts agreed on the existence of Autistic-like traits, which is the material issue where suicide risk is concerned.”

Johnson added: “Diagnosing Autism Spectrum Disorder is a specialised field, particularly in those who are high functioning. Fazel’s abstention on this point may have merely reflected that fact, rather than substantive disagreement with Kopelman. The wording of Judge Baraitser’s ruling suggests this to be the case.”

In an email, Dr. Derek Summerfield, an honorary senior clinical lecturer at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, agreed with Johnson, saying he had nothing to add.

Baraitser ruled:

“I preferred the expert opinions of Professor Kopelman and Dr. Deeley to those of Dr. Blackwood. Dr. Blackwood did not accept Professor Kopelman diagnosis of severe 109 depressive episode with psychotic features (from 2019) and he did not consider that Mr. Assange met the diagnostic threshold for an autism spectrum disorder.”

It is difficult to imagine it was a mistake by Dobbin to say that prosecution witness Fazel and defense witness Deeley did not agree that Assange was autistic. Dobbin misrepresented Fazel’s opinion, misleading the court.

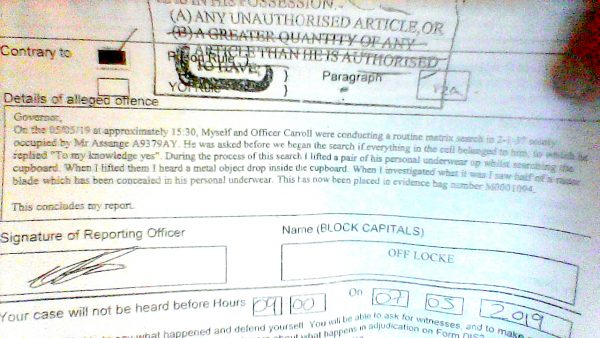

The Razor Blade Incident

Lewis, the lead prosecutor for the U.S., in his cross examination repeatedly tried to lead Kopelman to doubt Assange’s word that a razor blade and two cords were found in his cell at Belmarsh prison. Lewis said Kopelman should reconsider his diagnosis of Assange’s suicidal impulses in what Lewis argued was an absence of factual evidence and malingering on Assange’s part.

Lewis tried to establish that Assange was at no risk of killing himself. He said when Assange was first brought to Belmarsh he refused to answer questions about his mental state and then refused to see a psychiatrist until he had spoken to his legal team. “Surely alarm bells should have rung that a very intelligent man with a strong incentive to feign symptoms would not agree to see a psychiatrist until he saw his legal team?” Lewis said.

Lewis then grilled Kopelman on the razor blade incident, which Lewis said was never recorded in prison records and must have been made up by Assange.

Lewis: “It beggars belief the authorities would not have put that in their notes.”

Kopelman: “It is surprising they are not there.”

Lewis: “So you rely on the razor and cords as indication of suicide. If this didn’t happen would it alter your diagnosis?”

Kopelman: “But he has clinical depression independent of whether a razor was found. He has reported his intense suicidal preoccupations, he wrote farewell letters and a will, that I corroborated, and the other day pills were found in his cell.”

Lewis: “These factors are self reported by Mr. Assange.”

Kopelman then testified that Assange had been given a test designed to detect if a patient is exaggerating an illness or malingering (and he later on re-direct said Assange had passed such a test.)

Lewis: “Was that the Minnesota test?”

Kopelman: “No, it was the TOMM test.”

Lewis: “The TOMM is not a test for malingering.”

Kopelman: “Yes it is. TOMM stands for Test of Memory Malingering.”

It was a rare instance of Lewis being reduced to humiliated silence in the courtroom.

It grew worse for Lewis the next day, when Assange’s attorneys produced a prison report clearly showing the razor blade incident had been recorded—a charge sheet filled in by two wardens at Belmarsh prison.

In her judgement, Baraitser wrote:

“… the US submitted that it was strange that the finding of a razor blade should only be recorded as a disciplinary infraction rather than related to a suicide attempt, and that ‘enormous’ weight had been given to the incident by Professor Kopelman. However, I noted that Professor Kopelman recorded this incident faithfully and without embellishment. I did not find that he gave the incident undue weight but that he considered it as one of very many factors indicating Mr. Assange’s depression and risk of suicide. In short, I found Professor Kopelman’s opinion to be impartial and dispassionate; I was given no reason to doubt his motives or the reliability of his evidence.”

Transfer to the Medical Wing

Still another instance of the prosecution misleading the court about Assange’s health was revealed when a prison report showed prosecution witness Blackwood wrongly testified that the only reason Assange had been transferred to Belmarsh’s medical wing was simply to isolate him after prison officials were embarrassed by a leaked video on June 7, 2019 of Assange speaking with other inmates.

The prison report instead detailed Assange’s “uncontrolled suicidal urges” the same day he was transferred, which prompted a meeting of prison officials to decide what to do with Assange.

How he came to be put in health care isolation was a key moment during Blackwood’s testimony.

The prosecution witness asserted from the stand that if Assange had indeed suffered from severe depression, the prison authorities would have sent him for outside medical treatment. That they didn’t, showed Assange was not suffering as much as Kopelman had contended, Blackwood testified.

On cross examination, Assange attorney Fitzgerald first elicited from Blackwood that one reason the authorities sent Assange to the medical ward, isolated from other prisoners, was indeed because of “reputational damage” to prison officials caused by the release of the video.

But then Fitzgerald produced a prison document that said that at 2:30 pm on the day Assange was sent to the ward it was noted that he was exhibiting a risk of self harm.

Flashing anger, Fitzgerald spoke over Blackwood, demanding to know why Blackwood hadn’t put that in his report. Judge Baraitser interjected that the witness should be allowed to finish his answer.

Blackwood said there were multiple factors for why he was sent to the medical ward, and essentially broke down to admit that Assange’s thoughts of self-harm was one of them, though he neglected to mention that in his report.

Assassination: ‘Palpable Nonsense’

During his cross-examination of Kopelman, Lewis curiously brought up the report of Nils Melzer, the U.N. special rapporteur on torture, who visited Assange in 2019 in Belmarsh with a physician and a psychiatrist. Lewis went on about how false Melzer’s report was in stating, for instance, that nations were ganging up on Assange and that there had been threats of violence and even assassination.

“Melzer accused the U.S., U.K., Sweden and Ecuador of contributing to a campaign of public mobbing, defamation and also powerful political insults, humiliation, open threats and instigation of violence and assassination,” Lewis said, calling it “palpable nonsense.”

Though Lewis had not yet heard the testimony that would come eight days later of the UC Global partner and employee that the CIA had discussed plans with the security firm to kidnap or poison Assange, and had not yet known of the Yahoo! News report last month in which U.S. officials confirmed those plans, he should have been aware of this video:

Lewis should have known that Assange had been aware of possible CIA plans to kill him as early as 201o when the CIA refused to say if there were such plans after a Freedom of Information Act request:

CIA refuses to confirm or deny plot to assassinate WikiLeaks editor; open government-Obama style http://is.gd/gLvcn

— WikiLeaks (@wikileaks) November 6, 2010

Lewis was clearly misleading the court by dismissing those threats as “palpable nonsense.”

Assange’s lawyers may try to introduce evidence from the Yahoo! report at the hearing this week to bolster their case that Assange was negatively affected psychologically by such assassination plans and that he should not be extradited to a country that seriously contemplated killing him.

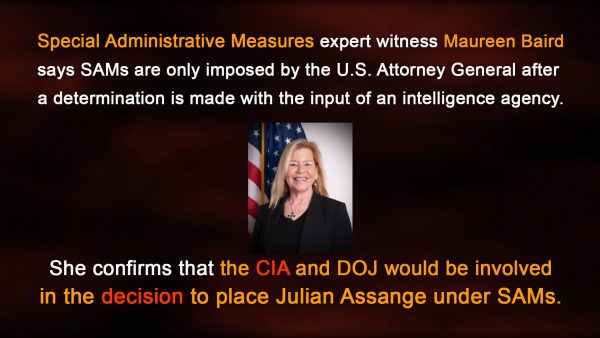

The Challenge for the US

That Assange is faking real illness and is not at high risk of suicide will be the central U.S. argument this week at the High Court, an argument it must win if the court is to overturn Baraitser’s decision not to extradite on health grounds.

At the Aug. 11 High Court hearing in which the U.S. won the right to appeal the ruling on Assange’s health, Dobbin said “part of the U.S. appeal is that Mr. Assange didn’t have an illness that came close” to being irresistible to suicide.

She argued that Assange couldn’t be so mentally ill that he would kill himself because “he had the fortitude to withstand the conditions” of the Ecuadorian embassy and left it “only when forced to.”

“He was willing to break the law at personal cost to himself,” she said. “He proved himself adept brokering diplomatic asylum, he remained a public figure including hosting a chat show on Russia Today and he sought to assist Edward Snowden.”

The U.S. faces a steep challenge to dismiss Kopelman’s testimony and overturn this assessment of it by the lower court judge, Baraitser:

“The overall impression is of a depressed and sometimes despairing man, who is genuinely fearful about his future. For all of these reasons I find that Mr. Assange’s risk of committing suicide, if an extradition order were to be made, to be substantial.

I am satisfied that, if he is subjected to the extreme conditions of SAMs, Mr. Assange’s mental health will deteriorate to the point where he will commit suicide with the ‘single minded determination’ described by Dr. Deeley.

First, Professor Kopelman offers the firm opinion that he is as confident as a psychiatrist can ever be that Mr. Assange will find a way to commit suicide. This opinion is based on a clinical evaluation following hours of clinical assessment with Mr. Assange, and a detailed knowledge of his history and circumstances.

I accepted Professor Kopelman opinion that Mr. Assange suffers from a recurrent depressive disorder, which was severe in December 2019, and sometimes accompanied by psychotic features (hallucinations), often with ruminative suicidal ideas. Professor Kopelman is an experienced neuropsychiatrist with a long and distinguished career. He was the only psychiatrist to give evidence who had assessed Mr. Assange during the period May to December 2019 and was best placed to consider at first-hand his symptoms.

He has taken great care to provide an informed account of Mr. Assange background and psychiatric history. He has given close attention to the prison medical notes and provided a detailed summary annexed to his December report. He is an experienced clinician and he was well aware of the possibility of exaggeration and malingering. I had no reason to doubt his clinical opinion.”

It might be a long two days for the U.S. prosecutors if their misleading arguments are exposed in court.