Discipline and Punish.

Federal funding cuts will only worsen school districts’ damaging dependence on debt.

Public school districts are bracing for cuts after the Trump administration’s decision to withhold $6.8 billion of education funding. But the financial squeeze is not new. For years, private finance has quietly shaped public education budgets. Schools have become deeply reliant on Wall Street debt to finance everything from basic infrastructure and classroom upgrades to day-to-day operations. The deeper schools fall into debt, the more they are bound by a set of financial rules that prioritize investors over students and teachers.

School districts turn to debt financing when they face costs that their immediate budgets cannot cover. Typically, these are costs associated with expensive, long-term capital projects; however, debt also occasionally covers run-of-the-mill budget shortfalls. Districts will issue municipal bonds, which investment funds purchase, effectively lending schools the money in exchange for a promise to repay the principal, plus interest and issuance fees. As Concordia University education scholar Eleni Schirmer notes, “debt is offered as a lifeline.” In the short term, it keeps the lights on. In the long term, it is too often a trap.

One issue is the terms under which schools borrow. To get low interest rates, districts must obtain a high credit rating from agencies like Moody’s or Fitch. These agencies assess “fiscal health” not by educational outcomes or improvements relative to spending, but by budget reserves, tax base wealth, and a district’s ability to withstand financial shocks. In practice, this means schools are expected to hoard cash, even if it means limiting spending on instruction, staff, or student services.

Consider the Los Angeles Unified School District. Today, its reserves stand at $6.4 billion, nearly 60 percent of its 2024 budget. Credit raters praise its restraint. Yet these savings have come at a cost: the district has stockpiled money by freezing instructional budgets.

The pressure to assuage Wall Street doesn’t stop there. School districts must also be nimble and, in finance parlance, “liquid” enough to respond to volatile market conditions. On the eve of the 2008 financial crisis, many districts adopted exotic debt instruments, such as “capital appreciation bonds” and “interest swaps.” These promised low upfront costs but carried steep long-term risks. When markets crashed, the deals backfired. Philadelphia schools spent $63 million in fees just to unwind its “toxic swaps” — more than its total spending on books or teaching materials.

More recently, Denver public schools transferred ownership of at least 31 schools to a shell corporation so it could lease the buildings back and issue debt securitized by the lease. This is a high-risk form of debt called “certificates of participation,” most often used when tax-backed borrowing is off the table. Half of total repayment on these revenue leases will go to interest alone.

Managing these arrangements requires expertise—not in education, but in finance. Over the past two decades, even as school districts have laid off teachers, they have hired former Wall Street professionals to navigate the municipal bond market. In Chicago, these experts pushed speculative debt schemes like auction-rate securities, assuring the public that they could manipulate interest rates and play long and short positions to minimize costs to taxpayers. In 2008, the auction-rate securities market melted down. The district had to pay $254 million in penalties just to terminate the deals. The Wall Street professionals’ “innovative” transactions may have cost Chicago taxpayers $100 million more than if schools had borrowed through traditional fixed-rate bonds.

These strategies reflect not fiscal prudence but fiscal capture. School districts have become ensnared in capital markets, playing a game they cannot win. They hoard reserves to avoid credit downgrades, gamble on complex debt to cover gaps, and cut educational spending to reassure investors.

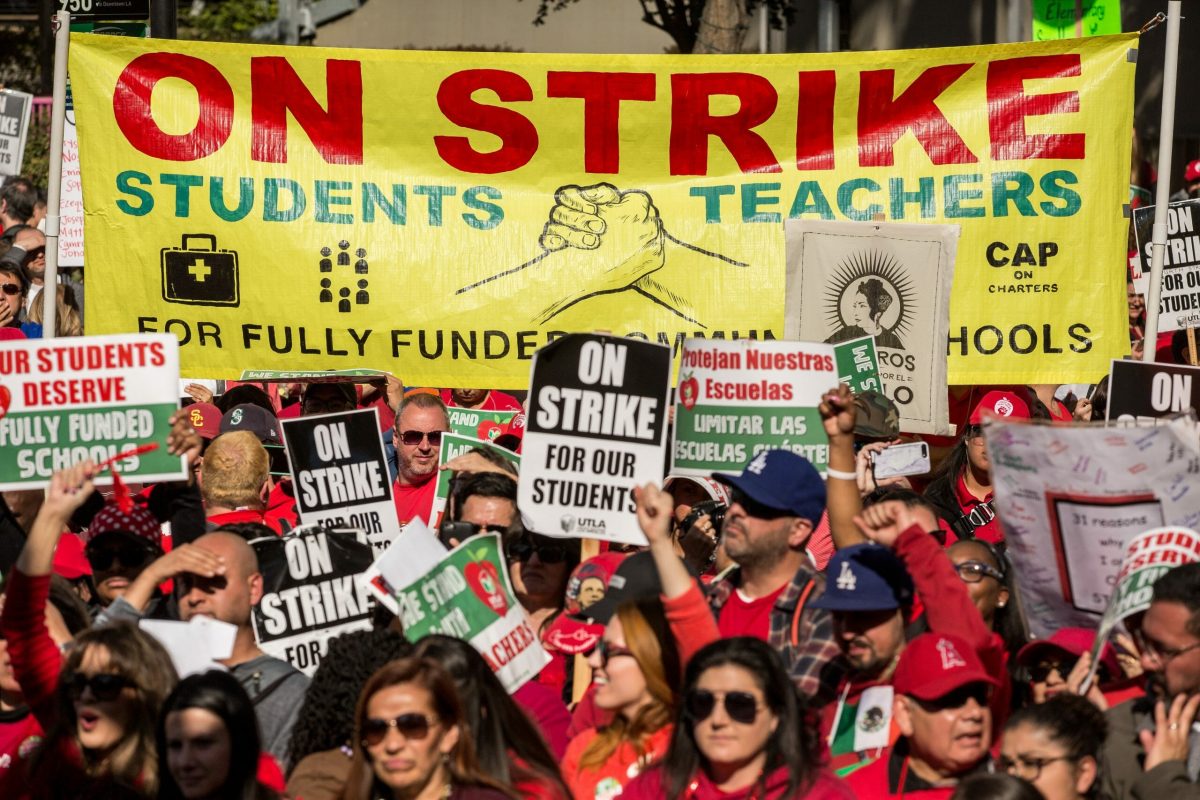

Meanwhile, students and frontline educational workers bear the costs: layoffs, swelling class sizes, crumbling buildings, and virtually non-existent climate adaptation. As federal funding shrinks and states are expected to fill the gap, the pressure to conform to Wall Street’s terms will only grow. Banks will condition future lending on further austerity. But neither students nor education workers can afford more cuts: they have not been the cause of wasteful spending but its victims, and they have sacrificed enough.

Another path is possible. After the 2008 crash, when the bond insurance industry collapsed and the fragility of municipal finance was laid bare, policymakers briefly floated serious alternatives: public credit rating agencies, collective bond pooling, regulation of transaction fees, and even direct Federal Reserve lending to schools and cities. Those ideas faded though the core problems persisted.

With budget cuts and a new economic downturn looming, it’s time to revisit them. Debt financing has a crucial role to play in public education, as major infrastructure projects require long-term investment. But it must be on fair and public terms, not predatory ones dictated by financial markets.

Schools exist to educate and care for our children, not to perform fiscal obedience for creditors. If we don’t reimagine how we fund them, the next crisis will once again fall hardest on the students and workers who have already sacrificed the most.