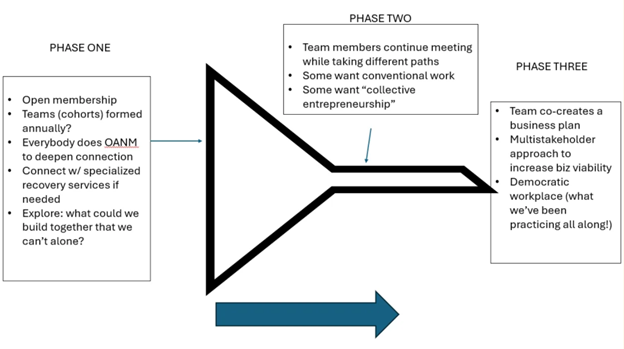

Above photo: The central promise of democracy, wrote social theorist Roberto Unger, should be to acknowledge and equip “the constructive genius of ordinary men and women”. A community incubator delivers on this promise by creating a “golden funnel”, open at one end and narrowing into a program of social and economic wellbeing at the other.

Let’s turn the neighborhood into an ecosystem for creating quality jobs.

Here’s a blueprint.

Let’s imagine something new has arrived in the neighborhood—a community incubator. It’s a little like a free health club, if you take health in the broadest sense—i.e., including social and economic health.

You could think of the incubator as working like a golden funnel turned on its side. It’s wide-open at one end (which most business incubators are not really) but it channels and directs the flow to particular places—like toward a good job. Or even a new business you co-own.

The logical home for a program like this is a community hub. You probably know this kind of place. It’s not a community center with yoga classes and senior swimming groups.

An authentic community hub feels grassroots-y and kinda political. It’s a space where people can meet up to organize campaigns, hold meetings, and maybe co-work. Three good examples are ReCity in Durham, the Festival Center in Washington DC, and the new Baltimore Community Commons in that city.

Community hubs are good at incubating organizations—i.e., non-profits. But rarely are they places where businesses are incubated.

A community incubator is a hybrid, a cross between a support group and a startup program. Actually, the former (the group) creates a process which leads to the latter (the launch of a new business). These two ideas—recovery (in the broadest sense) and collective entrepreneurship—are rarely tied together—in the U.S., at least.

So what does a community incubator do?

It invites any and all adult individuals, especially those who are in recovery from various conditions (incarceration, addiction, or just long periods of joblessness), to join a “workout” program—for free.

We know many in our communities justifiably feel they are unable to get back in “the game”. Here I’m proposing an open-access path to not only participating again but becoming a champion—i.e., someone with a strong sense of wellbeing.

Once you become a member of the incubator, you are no longer a random invidual—you’re part of a team (i.e., a cohort) which meets on a weekly or biweekly basis. This is where we all discuss what it can mean to get “back in shape”—i.e., ready to participate in the world, including the economy. (For individuals needing specialized recovery serivces, the incubator coordinates with other area programs.)

Here’s my crude representation of the phased approach of the incubator (it looks like a sideways funnel):

But you don’t participate here solo—the rest of your team is involved in supporting your wellness. And we’re all getting to know each other better.

For example, while incubator membership would be free, there’s one qualification: you have to participate in an ongoing offers and needs market process. This is a highly effective tool used by small groups to explore and then match up their talents and needs It offers a quick way to build solidarity among people who don’t know each other. (One group of skilled OANM practitioners is the highly innovative Kola Nut Collaborative in Chicago.)

Not Just Jobs: Let’s Talk about Co-creating Good Work!

Possibly the most visionary aspect of the community incubator is its potential to create dignified, meaningful jobs in democratic workplaces co-owned by team members. In places like northern Italy, Quebec, and South Korea, these liberatory workplaces already exist in the tens of thousands. For most Americans at this moment, the very term “liberatory workplaces” sounds either bitterly ironic or downright visionary.

To successfully imitate these non-U.S. models, we need to practice what community advocate Sam Pressler calls “civic alignment”—that equilibium reached when our enterprises keep in balance the forces of membership (the glue of commitment), revenue (the fuel of independence and innovation), and governance (the structure for good decision-making).

All of which means: with the right partner organizations, an incubator can turn a community hub into something new and potentially transformative—a site of quality job creation, by and for the community.

Here are some examples of partner organizations in these multistakeholder enterprises:

- Beyond sourcing philanthropy and donors, aim to create a dedicated community investment fund to support the incubator and invest in its businesses;

- And you’ll want to build a shared services platform (to connect with other incubators), developed by a team which practices “small software”—i.e., vision coding and relational tech;

- And as a multistakeholder enterprise, you’ll want to find other community partners (churches, civic groups) which subscribe to ideas such as “neighborhood economics”.

Equally importantly, these are jobs in enterprises which have been co-created by their worker-owners—an idea which many marginalized individuals might not imagine to be possible. (It’s a bit like applying Asset-Based Community Development principles to a small business model.)

This bottom-up process of quality job creation (the general term for it is cooperativism) has been used in most of the countries of the world for many generations—which surely testifies to the “constructive genius of ordinary men and women” referred to in the quote above from Roberto Unger.

This idea is not merely utopian. One inspiration for the incubator model I’ve described here is the methods used by Mondragon founder Fr. Josemaria Arizmendi—i.e., a mix of study groups and then a workplace-as-school of human development strategy.

While examples of this type of community-led economic development are scarse in the U.S., here is one good example in a large city (Denver) and here is another in rural North Carolina.

More to come on all these matters, y’all. And let me know if any of this resonates!