The U.S. war on drugs remains what it has long been.

Not a public health strategy, not even a serious global interdiction campaign, but a political weapon aimed at adversaries.

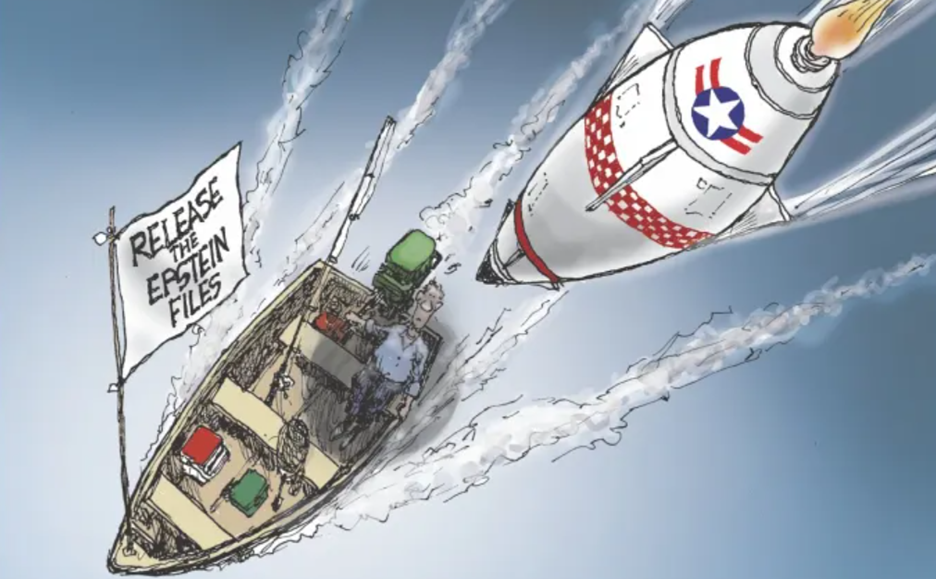

In October 2025, the United States cut a deal with China to reduce tariffs on imports tied to fentanyl — the synthetic opioid responsible for more than 70,000 U.S. overdose deaths annually. The tariff on these imports was lowered from 20% to 10% after a meeting between Donald Trump and Xi Jinping in Busan, South Korea, in which China agreed to work very hard to curb fentanyl related exports into the U.S. At almost the exact same time, the U.S. military was conducting lethal strikes on alleged drug-smuggling vessels off the coast of Venezuela — firing missiles into wooden boats and declaring victory in the war on drugs.

This contradiction isn’t subtle. Despite stronger regulation, Chinese intermediaries remain the world’s primary exporters of fentanyl precursors, like the controlled chemical piperidone, which are then used by narcotics cartel chemists in Mexico to manufacture the drug that floods U.S. streets. Yet instead of active cooperation with China’s authorities to target Chinese chemical companies and their marketing practices and structures, Washington simply reduced tariffs and praised China’s chemical industry regulation and enforcement.

Meanwhile, in Latin America, the U.S. has launched drone and missile strikes on what it claims are drug-trafficking vessels in Venezuelan waters — killing crew members without judicial process and justifying the events under narcotics law.

The U.S. war on drugs remains what it has long been: not a public health strategy, not even a serious global interdiction campaign, but a political weapon aimed at adversaries, while friendly partners and profitable trade relationships are protected — even when they are the very headwaters of the drug pipeline.

Bombing “Drug Boats” in Venezuela

In early September 2025, the U.S. military began a campaign of precision strikes on alleged Venezuelan narco-boats, ostensibly trafficking drugs into the United States and Europe. The targets were small fishing vessels — not container ships, not industrial chemical tankers, but wooden boats allegedly carrying narcotics for criminal networks.

The Pentagon framed the strikes as part of a broader anti-trafficking mission, even as details on the intelligence and legal basis for the attacks were withheld.

As documented in my earlier article, these attacks raise unanswered questions about their legality, the quality of targeting intelligence, and the disposable way the U.S. invokes drug trafficking to justify lethal force against sovereign nations — especially those out of favor in U.S. geopolitical strategy. Venezuela, under Nicolás Maduro, has long been subject to economic sanctions, coup attempts, and international isolation. The narco-state label serves as a flexible pretext for military escalation.

But if the U.S. were genuinely targeting the drug trade, it would have far bigger fish to fry than Venezuelan fishing boats. Which makes the next development all the more revealing.

Cutting Tariffs on Chinese Fentanyl Precursors

Just weeks after the Venezuelan strikes began, President Trump — who had long demanded China do more to stem fentanyl production and export — announced a reduction of U.S. tariffs on fentanyl-related imports from China. The tariff cut was a core part of a broader trade package that lowered total U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods from roughly 57% to 47%. Trump emphasized that the rollback was specifically tied to Beijing’s alleged cooperation on fentanyl, saying, after meeting Xi: “I believe they are really taking strong action.”

Despite signing a diplomatic statement of intent, China did not go as far as targeting chemical factory producers although it has toughened its regulatory regime. In return, the United States has simply gone ahead and made it cheaper for unscrupulous Chinese intermediaries to continue exporting the precursors that make fentanyl production possible in Mexico.

This was framed by U.S. officials not as a security compromise, but a milestone in cooperation — proof that diplomacy, not force, was the way to counter fentanyl production. Yet the brutal irony is this: the U.S. used drone strikes to blow up poor Venezuelan fishermen said to be moving “narcotics,” while rewarding the state whose factories make the chemicals used to produce fentanyl on an industrial scale.

The Political Weaponization of Drug Enforcement

The contrast exposes the real priorities behind U.S. drug policy:

- Alleged small-scale operators in uncooperative nations to U.S. corporate plunder are erased with military force.

- Industrial-scale suppliers in friendly or competitive nations are negotiated with diplomatically — even incentivized economically.

- No serious drug-war framework could justify this. But a geopolitical framework could: Venezuela is aligned with Russia, China, and Iran, and possesses vast oil reserves. China is a global manufacturing base and lender whose cooperation is crucial to U.S. rare earth mineral and semiconductor supply chains. That is what determines policy — not the drug itself or the number of dead Americans.

This is why the war on drugs has never followed the logic of drug interdiction. The U.S. does not bomb factories in China that produce fentanyl precursors. It does not impose asset freezes on large multinational chemical exporters. It does not intercept 40-foot containers filled with precursor chemicals on the high seas and seize the companies that ship them. That’s because the war on drugs isn’t about drugs. It’s about force projection — and about who is allowed to profit from the global drug economy.

Selective Enforcement Exposed

The fentanyl tariff cut is not a footnote. It is a policy admission that the U.S. is willing to make fentanyl cheaper to import — as long as the supply comes from a partner in a high-priority trade negotiation. It is a direct, tangible reward for China’s role in the fentanyl supply chain. And it happened within the same news cycle as the U.S. military declared victory over Venezuelan alleged “narco-boats.”

If the U.S. wanted to prevent fentanyl from entering its borders, it would regulate precursor chemicals at their industrial source, not destroy wooden boats in the Caribbean. No amount of military action in Venezuela — or Mexico, or Colombia — will stop fentanyl production as long as the precursors are produced legally, cheaply, and at scale by Chinese chemical exporters whose goods are welcomed on U.S. shores.

A Policy of Convenience, Not Principle

The implications are clear:

- Drugs are not treated as drugs. They are treated as political weapons.

- Venezuela is fair game for military action, because it’s on the wrong side of global corporate power.

- China is not, because its cooperation is needed for semiconductors, rare earth minerals, and other sectors critical to U.S. corporate and geopolitical interests.

- The tariffs on fentanyl-linked Chinese goods were not removed because the drug threat diminished. They were removed because the U.S. wanted concessions on trade — and because the Biden and Trump administrations alike prefer to make fentanyl a foreign scapegoat rather than address the domestic political economy of pharmaceutical addiction, medical malpractice, and domestic fentanyl distribution.

The U.S. drug war remains a screen — a shifting justification for geopolitical pressure, military force, and selective economic policy. The same government that shoots missiles at Venezuelan fishermen will lower tariffs on the chemicals used to make fentanyl, because drug control has never been the point. Power has. And as long as U.S. foreign policy is framed around the war on drugs, it will continue to enforce that war selectively — as a false justification to escape congressional approval for its military aggression, and never against its most profitable partners.