The Spanish government’s latest round of anti-protest laws are as worrying as they are laughably predictable. On top of criminalizing passive resistance, the new regulation considers actions such as uploading images of police violence to YouTube, or even Tweeting about a protest, to be punishable by fines as high a 600,000€, if you decide to protest in front of any so-called “Democratic Institutions”. As George Orwell argued, “A society becomes totalitarian when its structure becomes flagrantly artificial”.

Given that this trend is growing internationally, and rather than play a cat and mouse game where normal people have the losing hand, we can turn the tables and ridicule these sorts of reactionary, short sighted, desperate measures with our greatest assets: imagination, humor and the fact that we’re the good guys. The following article, written by Spanish art-ivists Amador Fernández-Savater and Leónidas Martín, offers 12 examples drawn from the last five decades poised to inspire and provoke. And check this out: so many people are eager to learn more about the how-to and history of this approach, that this has been the single most widely Facebook-shared article in eldiario.es’s history! We’ve also included some English hyperlinks to follow up on some of these leads and subtitled the one video in Spanish. Although written in reaction to the passage of the new law in Spain, we believe that their application and appeal is universal. Read on…

The objective of Spain’s new Citizen Security Law is very simple: to proscribe politics by criminalizing it, and withdrawing anything other than politics by politicians from circulation. This stunted, meager concept of democracy declares that decision-making is the exclusive right of political parties, public opinion the monopoly of experts, and that the sole role of the citizenry is to vote every four years.

The law was immediately dubbed the “Anti 15-M” law in social networks. In effect, these measures don’t hold up to the general and abstract character of a proper “law”. Instead, they’re very specifically directed against the new forms of on-the-ground citizen politics we’ve seen emerge in these last two and a half years: 15-M, Mareas (Citizen’s Tides), PAH, for example 1. While critics of the 15-M movement dismissed it as something meek and inoffensive, it’s now evident that its open, creative, and inclusive modes of action have posed a challenge to the powers that be.

It is certainly not the first time in the history of politics – and by this we mean, the surging increase of debate and decision-making by the people on issues of common life – that politics have come under threat: dictatorships, authoritative regimes and repressive laws, police management of public space, and so on. What then can we do when open, frontal confrontation is neither possible, nor the best of all options (because it’s useless, because it makes us feel despondent and crushes our voices, because it only leads to a trail of wounded, imprisoned protesters, etc.)?

In other, infinitely harsher situations than ours, the people managed to come up with subtle, intelligent and imaginative strategies to bypass repressive situations and laws. Below we present 12 stories of actions that can inspire us today to disobey the new law with humor, beauty, mobility, and a bit of camouflage.

Humour (or How to say it without saying it)

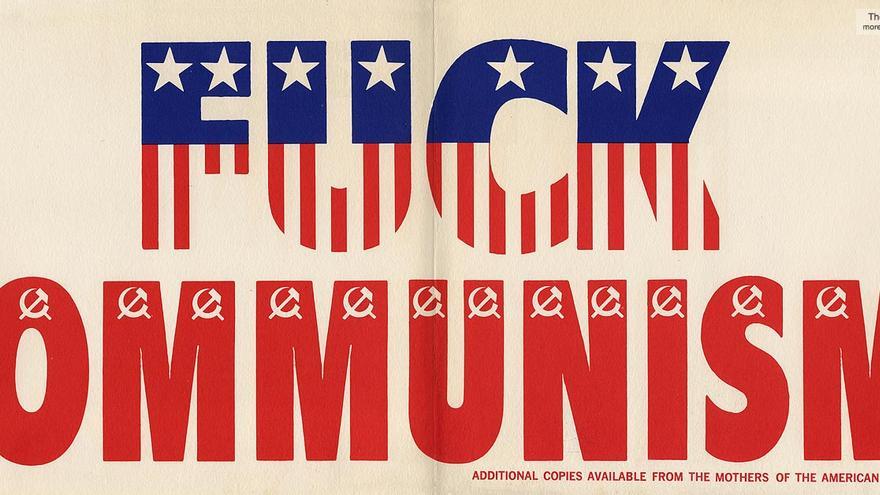

1: Fuck Communism in the USA

In the United States in the 60s, two words were absolutely forbidden. One, literally, was the word “fuck”. Writing it or saying it aloud could carry fines, or even prison sentences. The other was, both culturally and symbolically, “communism”. It was the great taboo, the evil spirit which the House Committee on Un-American Activities had decided to eradicate (and magnify, in considering anyone and everyone to be a suspect).

The Yippies, which was the creative activist group led by Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, decided to take matters into their own hands by organizing a citywide sticker and billboard campaign with the following slogan: “fuck communism”. There was a poster designed by Paul Krassner.

They were saying the forbidden (sometimes as a feint or while saying it without saying it), dodging censorship and criminalization, seeking complicity with intelligent observers able read between the lines and appreciate the genius of this operation.

For further investigation: Read Kurt Vonnegut’s thoughts on this poster.

2: The Orange Alternative in Poland

In the 80s, you needed guts and killer smarts if you wanted to go up against the Communist regime of Poland. Without them, you’d almost surely end up in prison for the rest of your life – or worse. Members of Pomaranczowa Alternatywa (Orange Alternative) stood out for their whimsical approach to protest and their creative use of the absurd.

They kicked off their career by painting dwarves over the regime’s attempts to whitewash all antigovernment graffiti away. These omnipresent dwarves soon took on lives of their own as symbols of Polish dissent. Hundreds of people dressed up as orange dwarves started to protest in the streets, demanding things such as the overthrow of Gargamel (!)

By using metaphor and allegory, saying without saying, they carried out dozens of protests without running the risk of being arrested – that is, without those arrests making the authorities look pretty ridiculous in the process. Really, how can anyone take a police officer seriously after seeing him arrest a protester for “participating in an illegal gathering of dwarves”?

For further investigation: Join “The Orange Alternative Revolution of Dwarves”

3: The Tighty-whitey Block in New York City

A few days before the protests against the World Economic Forum in February 2002, the Major of New York City digs up an old law (drafted in 1847, no less!) prohibiting the use of masks in the course of any public event. The restoration of the law has a very clear objective: to allow the police to compile a thorough photo archive of protesters.

The New Kids on the Black Block, a group of anti-globalization activists wise in the ways of guerrilla communication, scrutinize the law with the utmost attention. What the law literally says is that the “use of any kind of mask” is strictly prohibited. But, with a bit of creativity, many things can be pressed into service…and thus, the Tighty-whitey Block is born.

“Tighty-whities” is US slang for old school underpants. In a matter of hours, the New Kids acquired a truckload of more than a thousand of these underpants, had them printed with subversive messages and distributed among the protesters. What’s more, they produced a gigantic underpants-shaped banner as a rallying point for all who wanted – or needed – to protest in anonymity, even if it was with a pair of underpants covering their mugs.

Tighty-whities: underpants though they may be, masks they most definitely are not. So, the police are left impotent as hundreds of protesters march by with underpants over their faces. They can’t make arrests, much less build that photo archive – certainly not the kind of mugshots they were expecting!

Camouflage (or, how to break the rules of the game from inside)

4: Argentina’s 501 Movement

Voting is compulsory in Argentina, but the National Electoral Code exempts anyone who’s 500 kilometers or more away from their home. On election day 1999 a group of young people invited anyone feeling dissatisfied with the electoral routine to make their way to a location 501 km away from their place of residence, as a way of expressing that the true meaning of democracy can’t be reduced to choosing from among what are, essentially, identical options every four years.

All the participants certified before police that, on election day, they would be 501 km away from their place of residence. Free, collective travel arrangements were provided from Buenos Aires to Sierra de la Ventana, where a festival was held. Unsurprisingly, they were accused of being “anti-political”, “anti-democratic”, and blah, blah, blah. But they countered, in their “Open Letter to Voters”, that right there at kilometer 501 they had reclaimed the true meaning of democracy, not as a perfunctory formality of the Necessary and Inevitable, but rather as a transformation of the extant, by everyone and for everyone.

For further investigation: “El movimiento 501, la “Carta a los votantes” y la spanish revolution” (in Spanish).

5: The Sex Pistols on the Thames

5: The Sex Pistols on the Thames

It’s mid-1977, Queen Elizabeth’s Jubilee is drawing near and the Government and the Royal House are desperate to avoid any critical actions. Following this logic, the Sex Pistols, authors of the song “God Save the Queen”, are expressly forbidden from playing on the British mainland.

The Pistols’ reaction to the ban is legendary. Instead of throwing in the towel, the band rent a boat for the occasion (aptly named the “Queen Elizabeth”), and on the 7th of June, the same day as the Royal March, they play a gig smack in the middle of the River Thames. Lest we forget, while the official order expressly prohibits them from playing on British mainland, it doesn’t say anything about rivers and waterways.

The stunt was so successful that it sent shockwaves through the media. That same week, their single “God Save the Queen” reached number one in the British charts. But, given that the song was banned, their chart-topping success could neither be announced on television, nor played on the radio. It was the only time in history that there has been no number one song.

6: Belarus’ Revolution Through Social Networks

Belarus, July 2011. Frustration over the economic crisis reaches its peak. President Alezander Lukashenko’s authoritative regime forbids all types of protest, while police repress all dissent. In response, the “Revolution Through Social Networks” appeared, a public call to gather in the streets to applaud, or to synch all mobile phones and make them ring at the same time. In this (apparently inoffensive) manner, thousands of people managed to turn a handful of everyday gestures into powerful expressions of dissent.

Mobility (or how to not become a target for your adversaries)

7. Lavapiés 15, Madrid

Located at its namesake address in the Lavapies district of Madrid, Lavapies 15 was a squat back in 1996. An official eviction order was drawn up within six months of its existence. The dwellers of Lavapies 15 sealed the door and pretended to hole up inside, the standard procedure for squats at that time (very heroic perhaps, but both useless and frustrating in the end).

So, as a hundred police agents and a helicopter searched the house, the squatters made their escape over rooftops, making obvious the disproportionate, unjustified and repressive deployment. It’s even rumored that some squatters actually stood by the door, mingling with the rest of the onlookers, to witness their own eviction.

“Resistance doesn’t have to equal suffering, taking the piss is another form of struggle”, they explained in regards to their action.

For further investigation: Read a short excerpt from “The Exteriority Crisis: From the City Limits and Beyond” on “The Ghosts” of Lavapies 15.

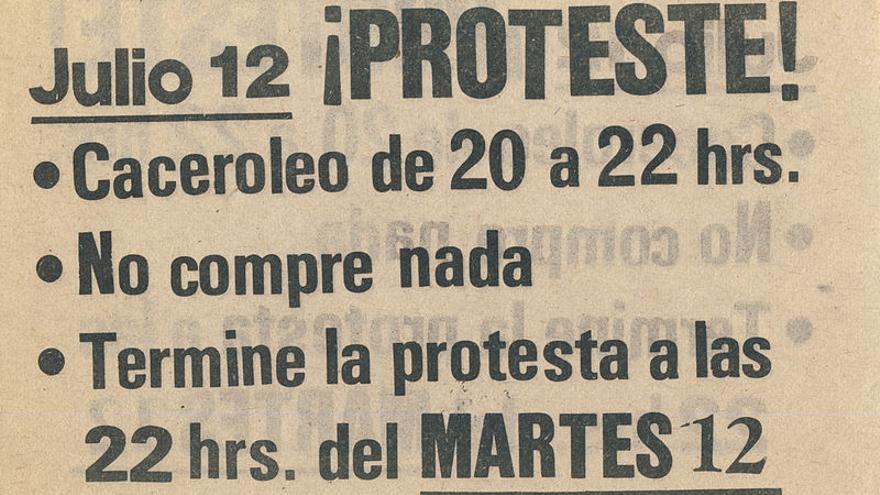

8: Chile’s National day of Protest

Chile, July 1983. Pinochet’s dictatorship is 10 years old, and the copper mine workers celebrate the anniversary by holding a national strike. The copper mines were the backbone of the country’s economy at the time, so the dictator’s response was swift. Hundreds of troops and various police forces surround the mines, with orders to shoot anyone supporting the strike. Bloodshed seems inevitable. However, it didn’t turn out that way.

Barely a day before the beginning of the strike, the leaders and spokespersons of the worker’s movement decide to change strategies. Rather than having the miners work stoppage be the only means of protest, they called for the first National Day of Protest, with many decentralized actions throughout the country. For example, people were encouraged to drive their cars at a snail´s pace through the main highways and thoroughfares of Chile, creating epic traffic jams all over the country; or to turn the lights on and off in their houses; or to incessantly bang pans and pots at nightfall. This was the birth of the cacerolazo, a mode of protest still very much in use nowadays.

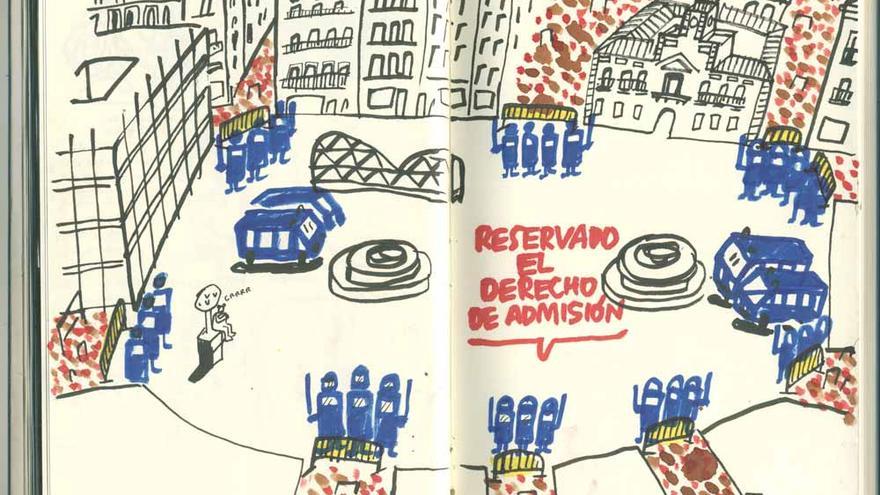

9: The (non) Battle of Puerta del Sol, Madrid

Tuesday, August 2nd 2011, the police unceremoniously clear out the remains of the recent occupation of Puerta del Sol, Madrid’s famous main square. Specifically, the info booth left there by the 15-M Movement. They tear down the beautiful plaque that read “We slept, we awoke. The square is taken”, and dump it in the trashbin. Thousands of citizens, feeling suddenly erased from the map, spontaneously gather to reconquer the square.

Lines of police blocked all entry points, while armored police vans stood guard over an empty square. Suddenly someone shouts, “Ciao, ciao, ciao, nos vamos a Callao” (“Ciao, ciao, we’re moving to Callao” – one of the neighboring squares). The slogan is quickly picked up. Rather than confront the police, protesters decide to turn their backs on them. Change of perspective, change of scenery, change in the dialogue, change of interlocutors, and change of emotions. Instead of uselessly screaming in the face of impassive policemen, 15-M decides to branch out all over the city. A seemingly helpless situation turns into one of empowerment. A joyous evasion.

The police garrison at Sol remains entrenched in position, protecting nothing. A day goes by, then two, three…such a level of police presence is unwarranted, and on the fourth day, they are told to stand down. Then, on the night of August 5th, the people happily re-enter the now liberated square in a great march.

For further investigation: a text Amador wrote describing the events (translation not ours)

The (Non) Battle of Sol as seen by Enrique Flores. The bubble reads “We Reserve the Right to Refuse Admission”

The (Non) Battle of Sol as seen by Enrique Flores. The bubble reads “We Reserve the Right to Refuse Admission”Beauty (or how art disarms brute force)

10: The pianist at Gezi Park (Istanbul)

During the June 2013 protests and prior to the final eviction of Gezi Park in Istanbul, president Erdogan had given an ultimatum to the demonstrators.

7 P.M. on the 12th of June was the chosen hour. Everything was primed for a police charge: emergency crews, gas masks, media, barricades…but just as the clashes began and the teargas exploded, there came a sound – neither war cry nor firearms, but music: The Beatles’ “Let It Be”. A piano had appeared from nowhere, and a hooked-nosed skinny kid with a hat was playing “Imagine” by John Lennon and “Bella Ciao”. Just then, everyone stopped what they were doing and gathered: they sat, applauded and sang together.

The pianist was a German of Italian origin, who’d been travelling throughout Europe carrying a message of peace. He had made the piano himself, asserting that his music calmed the police and, somehow, protected the demonstrators. Erdogan didn’t dare crush this community sprung around music. It would have been too brutal an image to expose to the world.

(Here you can see the Solfónica, Madrid’s own protest-march classical ensemble and choir, producing the same effect during the Spanish general strike of November 14, 2012)

What you have just read is a fragment of a chronicle of those days in Istanbul written by our friend José Fernández-Layos. You can read the full account here in Spanish

11: “Standing Man” in Istanbul

When Erdogan finally – without warning – attacked Gezi Park and evicted the occupiers, he issued a threat: anyone trying to enter Taksim Square (adjacent to the park) would be accused of terrorism. Thousands of people tried to enter forcibly or via the barricades, but it was all in vain. Until one man waltzed through, posing as any other tourist, with no gasmask or bandanna covering his face, and simply stood in front of the Atatürk building, just standing there quietly for hours. It soon became a trending topic on Twitter and the police arrested him, but it was too late: many other “standing men” or “still persons” like him replicated the action in an incessant dribble on squares throughout the country. Bit by bit, Taksim was reclaimed. It was practically impossible to steer public opinion that these people were terrorists, when it was plain to see that they were simply people standing there…although, in fact, everyone knew that they were defying the government.

What you have just read is a fragment of another chronicle written by our friend José Fernández-Layos about those days in Istanbul. You can read the full account here in Spanish

12: The Reflectors in Barcelona

Around the time of the first anniversary of the 15-M protests, the powers that be had flipped the switch on their repressive countermeasures to criminalize street protest. Playing into this dynamic robs the streets of plurality, “de-democratizing” protest and reducing it to small groups, very homogenous and easy to identify and codify. Enter The Reflectors with the slogan, “We won’t play that game, let’s break the codes”.

The Reflectors look like superheroes out of a Marvel comic book, but they are in fact normal people with two or three very un-normal characteristics: their brilliant costumes made out of aluminum foil, the Reflecto-Ray and the Reflecto-Cube.

Used correctly, the Reflecto-Ray reflects sunlight over police cameras recording protesters. The Reflecto-Cube can be used in two different ways: as a festive prop when any protest starts getting boring, and as an antidote to police charges.

This second application of the Reflecto-Cube was put to the test for the first time in Barcelona, during the last general strike on November 14th, 2012. The populist protests of the morning had finished, and police entered the Plaza de Cataluña square in full force, striking everyone in their path with their batons. People panicked. Terrified protesters started running towards neighboring Paseo de Gracia and, at that exact moment, the Reflecto-Cube erupted onto the scene. After a good while trying to get to grips with it, the riot police decided to dispose of it by pushing it back towards The Reflectors, who proceeded to send it back to the police, starting a game of absurd beach volleyball that radically transformed the atmosphere in the square from sheer panic to all-out party in less than a minute.

For further investigation: Find out more about The Reflectors’ adventures here.

Do you know of any other similar actions? Tell us your story in the comments, and we will try and update this article with them.

This first compilation was written by Leónidas Martín Saura (Enmedio Collective) and Amador Fernández-Savater, with the indispensable help of Sabino Ormazábal and his horseflies, Juan Gutiérrez, Frauke Schultz, Lawrence of Arabia, Nuria Campabadal, Beautiful Trouble, José Fernández-Layos, Margarita Padilla and Franco Ingrassia.

The principles of the Guerrilla Movement are, ultimately, two: mobility as the best defensive weapon; and thought, as the best kind of attack. Neutralizing the enemy’s targets and the conversion of each individual into a sympathizer and friend are the keys to victory.

BONUS! Here’s a coda of sorts to this compilation, written by the co-author Leónidas Martín and published in our Metablog: A call for the World Record of people shouting, “You’ll never own a house in your whole fucking life”