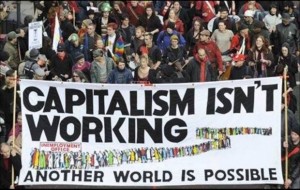

Above Photo: A banner reading ‘Capitalism isn’t working’ at the Occupy London Stock Exchange protest. Photograph: Oli Scarff/Getty Images

An exclusive excerpt from David Frayne’s contribution to ROAR Issue #2, ‘The Future of Work’, scheduled for release in June/July.

If work is vital for income, social inclusion and a sense of identity, then one of the most troubling contradictions of our time is that the centrality of work in our societies persists even when work is in a state of crisis. The steady erosion of stable and satisfying employment makes it less and less clear whether modern jobs can offer the sense of moral agency, recognition and pride required to secure work as a source of meaning and identity. The standardization, precarity and dubious social utility that characterize many modern jobs are a major source of modern misery.

Mass unemployment is also now an enduring structural feature of capitalist societies. The elimination of huge quantities of human labor by the development of machine technologies is a process that has spanned centuries. However, perhaps due to high-profile developments like Apple’s Siri computer assistant or Amazon’s delivery drones, the discussion around automation has once again been ignited.

An often-cited study by Carl Frey and Michael Osborne anticipates an escalation of technological unemployment over the coming years. Occupations at high risk include the likes of models, cooks and construction workers, thanks to advances such as digital avatars, burger flipping machines and the ability to manufacture prefabricated buildings in factories with robots. It is also anticipated that advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning will allow an increasing quantity of cognitive work tasks to become automated.

What all of this means is that we are steadily becoming a society of workers without work: a society of people who are materially, culturally and psychologically bound to paid employment, but for whom there are not enough stable and meaningful jobs to go around. Perversely, the most pressing problem for many people is no longer exploitation, but the absence of opportunities to be sufficiently and dependably exploited. The impact of this problem in today’s epidemic of anxiety and exhaustion should not be underestimated.

What makes the situation all the crueler is the pervasive sense that the precarious victims of the crisis are somehow personally responsible for their fate. In the UK, barely a week goes by without a smug reaffirmation of the work ethic in the media, or some story that constructs unemployment as a form of deviance. The UK television show Benefits Street comes to mind, but perhaps the most outrageous example in recent times was not from the world of trash TV, but from Dr. Adam Perkins’ thesis, The Welfare Trait. Published last year, Perkins’ book tackled what he defined as the “employment-resistant personality”. Joblessness is explained in terms of an inter-generationally transmitted psychological disorder. Perkins’ study is the most polished product of the ideology of work one can imagine. His study is so dazzled by its own claims to scientific objectivity, so impervious to its own grounding in the work ethic, that it beggars belief.

It seems we find ourselves at a rift. On the one hand, work has been positioned as a central source of income, solidarity and social recognition, whereas on the other, the promise of stable, meaningful and satisfying employment crumbles around us. The crucial question: how should societies adjust to this deepening crisis of work?

This is an excerpt from David Frayne’s “Towards a Post-Work Society”, which will appear in ROAR Issue #2, The Future of Work, scheduled for release in June/July.