Above Photo: By Sam Owens.

Editor’s Note: This is part one of a two-part series. For the second part, click here.

Follow the pills and you’ll find the overdose deaths.

The trail of painkillers leads to West Virginia’s southern coalfields, to places like Kermit, population 392. There, out-of-state drug companies shipped nearly 9 million highly addictive — and potentially lethal — hydrocodone pills over two years to a single pharmacy in the Mingo County town.

Rural and poor, Mingo County has the fourth-highest prescription opioid death rate of any county in the United States.

The trail also weaves through Wyoming County, where shipments of OxyContin have doubled, and the county’s overdose death rate leads the nation. One mom-and-pop pharmacy in Oceana received 600 times as many oxycodone pills as the Rite Aid drugstore just eight blocks away.

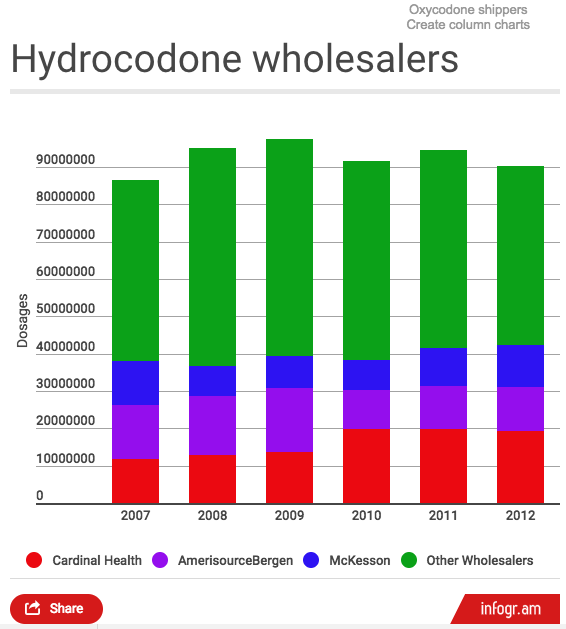

In six years, drug wholesalers showered the state with 780 million hydrocodone and oxycodone pills, while 1,728 West Virginians fatally overdosed on those two painkillers, a Sunday Gazette-Mail investigation found.

The unfettered shipments amount to 433 pain pills for every man, woman and child in West Virginia.

“These numbers will shake even the most cynical observer,” said former Delegate Don Perdue, D-Wayne, a retired pharmacist who finished his term earlier this month. “Distributors have fed their greed on human frailties and to criminal effect. There is no excuse and should be no forgiveness.”

The Gazette-Mail obtained previously confidential drug shipping sales records sent by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration to West Virginia Attorney General Patrick Morrisey’s office. The records disclose the number of pills sold to every pharmacy in the state and the drug companies’ shipments to all 55 counties in West Virginia between 2007 and 2012.

The wholesalers and their lawyers fought to keep the sales numbers secret in previous court actions brought by the newspaper.

The state’s southern counties have been ravaged by a disproportionate number of pain pills and fatal drug overdoses, records show.

The region includes the top four counties — Wyoming, McDowell, Boone and Mingo — for fatal overdoses caused by pain pills in the U.S., according to CDC data analyzed by the Gazette-Mail.

Another two Southern West Virginia counties — Mercer and Raleigh — rank in the top 10. And Logan, Lincoln, Fayette and Monroe fall among the top 20 counties for fatal overdoses involving prescription opioids.

While the death toll climbed, drug wholesalers continued to ship massive quantities of pain pills.

Mingo, Logan and Boone counties received the most doses of hydrocodone — sold under brand names such as Lortab, Vicodin and Norco — on a per-person basis in West Virginia. Wyoming and Raleigh counties scooped up OxyContin pills by the tens of millions.

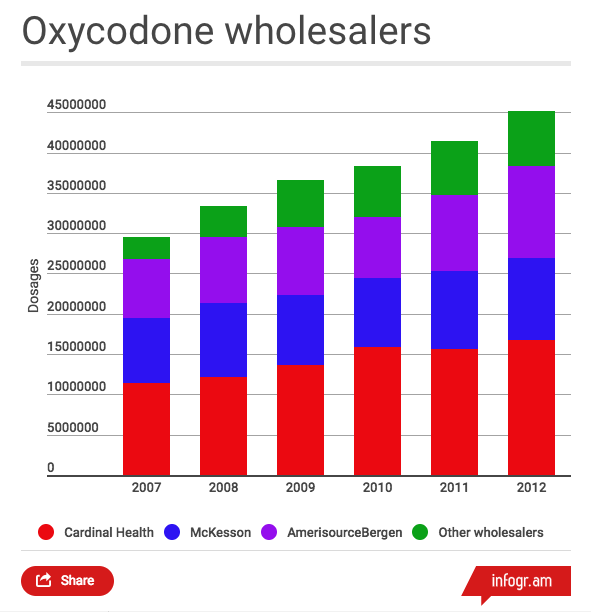

The nation’s three largest prescription drug wholesalers — McKesson Corp., Cardinal Health and AmerisourceBergen Drug Co. — supplied more than half of all pain pills statewide.

For more than a decade, the same distributors disregarded rules to report suspicious orders for controlled substances in West Virginia to the state Board of Pharmacy, the Gazette-Mail found. And the board failed to enforce the same regulations that were on the books since 2001, while giving spotless inspection reviews to small-town pharmacies in the southern counties that ordered more pills than could possibly be taken by people who really needed medicine for pain.

As the fatalities mounted — hydrocodone and oxycodone overdose deaths increased 67 percent in West Virginia between 2007 and 2012 — the drug shippers’ CEOs collected salaries and bonuses in the tens of millions of dollars. Their companies made billions. McKesson has grown into the fifth-largest corporation in America. The drug distributor’s CEO was the nation’s highest-paid executive in 2012, according to Forbes.

In court cases, the companies have repeatedly denied they played any role in the nation’s pain-pill epidemic.

Their rebuttal goes like this: The wholesalers ship painkillers from drug manufacturers to licensed pharmacies. The pharmacies fill prescriptions from licensed doctors. The pills would never get in the hands of addicts and dealers if not for unscrupulous doctors who write illegal prescriptions.

In other words, don’t blame the middleman.

“The two roles that interface directly with the patient — the doctors who write the prescriptions and the pharmacists who fill them — are in a better position to identify and prevent the abuse and diversion of potentially addictive controlled substance,” McKesson General Counsel John Saia wrote in a recent letter released by the company last week.

But the doctors and pharmacists weren’t slowing the influx of pills.

Cardinal Health saw its hydrocodone shipments to Logan County increase six-fold over three years. AmerisourceBergen’s oxycodone sales to Greenbrier County soared from 292,000 pills to 1.2 million pills a year. And McKesson saturated Mingo County with more hydrocodone pills in one year — 3.3 million — than it supplied over five other consecutive years combined.

Year after year, the drug companies also shipped pain pills in increasing stronger formulations, DEA data shows. Addicts crave stronger pills over time to maintain the same high.

“It starts with the doctor writing, the pharmacist filling and the wholesaler distributing. They’re all three in bed together,” said Sam Suppa, a retired Charleston pharmacist who spent 60 years working at retail pharmacies in West Virginia. “The distributors knew what was going on. They just didn’t care.”

‘She just got hooked’

Mary Kathryn Mullins’ path of dependence took her to pain clinics that churned out illegal prescriptions by the hundreds, pharmacies that dispensed doses by the millions and, on many occasions, to a Raleigh County doctor who lectured her about the benefits of vitamins but handed her prescriptions for OxyContin.

“She’d get 90 or 120 pills and finish them off in a week,” recalled Kay Mullins, Mary Kathryn’s mother. “Every month, she’d go to Beckley, they’d take $200 cash, no insurance, and the pills, they’d be gone within a week.”

Mary Kathryn Mullins’ addiction, her mother said, started after a car crash near her home in Boone County. Her back was hurting. A doctor prescribed OxyContin.

“She got messed up,” Kay Mullins said. “They wrote her the pain pills, and she just got hooked.”

Kay Mullins has a hard time talking about the 10 years that followed, all the lies her daughter told to cover her addiction, stealing from her brother, the time she shot herself in the stomach in an attempt to end her life.

Mary Kathryn Mullins would go to dozens of doctors for prescriptions. She was a “doctor shopper.”

Her mother can’t recall most of the doctors by name. She said she believes the doctor who talked to her daughter about vitamins was recently in the news after being charged with prescription fraud. Many rogue pain clinics have been shut down in recent years.

“She’d go to his house in the woods for prescriptions,” Kay Mullins said.

There also were stops at multiple pharmacies in Madison, Logan, Beckley and Williamson. Mary Kathryn Mullins always would find a way to get pills. She kept most for herself, but sometimes she sold them to others, her mother said.

“It tore my family up,” said Kay Mullins, who works at a flower shop in Madison. “You don’t sleep. One time she would be OK, and you think she would come out of it, but then something else happens.”

Last December, Mary Kathryn Mullins’ hunt for pain pills led her to South Charleston. A doctor prescribed her OxyContin and an anti-anxiety medication, her mother said. A pharmacy in Alum Creek filled it.

Two days later, she stopped breathing in her bed. Her brother, Nick Mullins, a Madison police officer, responded to the 911 call. He tried chest compressions, but he could not revive his sister.

At age 50, Mary Kathryn Mullins was dead.

After the funeral, her mother had one last thing to do. She found an appointment reminder card for Mary Kathryn Mullins’ next scheduled visit to the doctor who wrote her final prescription. She dialed the phone number of the doctor’s office and spoke to the receptionist.

“I told her my daughter was there Dec. 20,” Kay Mullins recalled. “I said, ‘Y’all wrote these prescriptions, and she’s gone Dec. 23. I just wanted to let you know she won’t be back.’”

Drug wholesalers made billions

In the drug distribution industry, they’re called the “Big Three” — McKesson, Cardinal Health, AmerisourceBergen — and they bear no resemblance to the mom-and-pop pharmacies that ordered massive quantities of the drugs the wholesalers delivered in West Virginia.

The Big Three wholesalers together are nearly as large as Wal-Mart, with total revenues of more than $400 billion. Their revenues account for about 85 percent of the drug distribution market in the U.S.

Between 2007 and 2012 — when McKesson, Cardinal Health and AmerisourceBergen collectively shipped 423 million pain pills to West Virginia, according to DEA data analyzed by the Gazette-Mail — the companies earned a combined $17 billion in net income.

Over the past four years, the CEOs of McKesson, Cardinal Health and AmerisourceBergen collectively received salaries and other compensation of more than $450 million.

In 2015, McKesson’s CEO collected compensation worth $89 million — more money than what 2,000 West Virginia families combined earned on average.

“What’s most remarkable is that the boards of the companies are paying the CEOs as if they were innovators and irreplaceable entrepreneurs, when in fact they are just highly paid middlemen, betting on market consolidation and ever-rising drug prices,” said Ken Hall, international secretary-treasurer of the Teamsters union.

Last month, the Teamsters sent a letter to McKesson board members urging them to investigate allegations raised by Morrisey in a lawsuit he filed against the company earlier this year. The complaint alleges McKesson “flooded” West Virginia with pain pills and gave bonuses and commissions to employees based on sales of highly addictive prescription drugs. The Teamsters’ pension funds hold a stake in McKesson.

In a letter to the Teamsters released by McKesson last week, the company denied it gave incentives to executives and other personnel for sales of controlled substances.

McKesson added Morrisey’s lawsuit assigns blame to drug wholesalers for West Virginia’s opioid crisis “without acknowledging the role played by doctors, pharmacists and the regulatory agencies that oversee doctors and pharmacists.”

“McKesson’s shipments were in response to orders placed by these registered entities,” the company’s chief lawyer wrote. “Thus, McKesson lawfully shipped controlled substances to registered pharmacies.”

A spokesman for AmerisourceBergen suggested health experts and law enforcement authorities would be better able to comment on whether there’s a link between pain-pill volumes and overdose deaths.

Cardinal Health said it shipped 3.4 billion doses of medication in West Virginia between 2007 and 2012. So hydrocodone and oxycodone sales made up about 17 percent of the company’s shipments.

“All parties including pharmacies, doctors, hospitals, manufacturers, patients and state officials share the responsibility to fight opioid abuse,” said Ellen Barry, a spokeswoman for Cardinal Health.

In Southern West Virginia, many of the pharmacies that received the largest shipments of prescription opioids were small, independent drugstores like ones in Raleigh and Wyoming counties that ordered 600,000 to 1.1 million oxycodone pills a year. Or they were locally owned pharmacies in Mingo and Logan counties, where wholesalers distributed 1.4 million to 4.7 million hydrocodone pills annually.

By contrast, the Wal-Mart at Charleston’s Southridge Centre, one of the retail giant’s busiest stores in West Virginia, was shipped about 5,000 oxycodone and 9,500 hydrocodone pills each year.

Firms shipped stronger pain pills

At the height of pill shipments to West Virginia, there were other warning signs the prescription opioid epidemic was growing.

Drug wholesalers were shipping a declining number of oxycodone pills in 5 milligram doses — the drug’s lowest and most common strength — and more of the painkillers in stronger formulations.

A DEA agent warned Morrisey’s aides about the disturbing trend in January 2015, according to an email released by the attorney general in response to a Freedom of Information Act request from the Gazette-Mail.

Between 2007 and 2012, the number of 30-milligram OxyContin tablets increased six-fold, the supply of 15-milligram pills tripled and 10-milligram oxycodone nearly doubled, the DEA records sent to Morrisey’s office show.

In the email to Morrisey, DEA agent Kyle Wright said the higher-strength oxycodone pills were commonly abused.

The DEA agent sent Morrisey’s office a separate email about hydrocodone shipments to the state. West Virginia pharmacies were mostly buying 10-milligram hydrocodone tablets — the most potent dosage at the time.

Once hooked on painkillers, addicts typically demand higher and higher doses.

Chelsea Carter, a recovering 30-year-old addict who now works as a therapist at a drug treatment center in Logan County, remembers crushing, snorting and injecting OxyContin — always wanting the strongest pills she could get her hands on. She once shot up with eight to 10 doses of oxycodone, passed out and woke up with the needle still stuck in her arm.

“You’re turned on to this potent substance, and your tolerance grows,” said Carter, who quit using pills in 2008, the day she went to jail after taking part in a theft ring that sold stolen goods for painkillers.

“When they handcuff you, and you walk through the doors, and you’re in an orange jumpsuit and they slam the doors behind you, that’s when you wonder, ‘is two to 20 years worth it for one OxyContin?’” Carter said. “That’s when I hit my knees and prayed, ‘Lord, if you ever bring me out of this, I’ll never touch another drug again.’”

The addicted come to see Carter at the clinic just off Main Street in downtown Logan. They want to get off pain pills or heroin — a street drug causing more and more overdose deaths in West Virginia every year.

They talk to Carter, eight to 10 of them a day. They’ve lost children, parents, grandparents. They’ve lost homes. They’re tired of living that way.

Carter listens and tells them her story, how every day she wakes up and makes a decision not to use pills.

“I’ve buried a lot of friends from drug addiction,” Carter said. “I don’t want to bury another one.”

Her trail follows the direction of hope.

Gazette-Mail staff writer Andrew Brown contributed to this story.