“The press does not simply publish information about trials but guards against the miscarriage of justice by subjecting the police, prosecutors, and judicial processes to extensive public scrutiny and criticism.” – Chief Justice Warren E. Berger

Legal proceedings surrounding the politically-charged, precedent-setting prosecution of investigative journalist Barrett L. Brown have taken another disconcerting turn as the government has requested a gag order to be placed on both Brown and his defense team.

Brown, who was arrested during a September 2012 raid on his Dallas apartment, is currently indicted on 17 felonies and has spent over 300 days in pre-trial federal detention. He potentially faces over a century in federal prison.

On Wednesday, September 4, a judge will decide whether or not the government will be permitted to prohibit Brown and his defense team from speaking to the press.

Among other charges, authorities have slapped him with multiple counts of credit card fraud, despite their showing zero evidence that he intended to profit from posting this information on his research wiki, Project PM. They have also charged him with threatening a federal officer.

Much has already been written about Brown and what led to his arrest, but perhaps the most shocking accusation leveled by federal prosecutors is that, in the course of Brown’s research into and subsequent reporting on the murky world of private intelligence contractors, he pasted a link into an internet chat space that clicked through to emails hacked and leaked by Anonymous.

These emails, which incidentally contained unencrypted credit card information as well as other personal identifiers, were freed from the servers of the intelligence firm Stratfor.

Brown’s case has rightfully become a rallying cry for journalists, information freedom activists and critics of prosecutorial overreach. Linking to source documents – like Brown’s linking to the leaked Stratfor emails in the course of his research and reporting – has become critical journalistic practice. As Peter Ludlow writes in the Nation, “Brown’s case is a good—and under-reported—reminder of the considerable risk faced by reporters who report on leaks.”

The sheer number of years Brown faces in prison – over a century – starkly contrasts with the potential sentence the actual hacker faces: a maximum of 10 years.

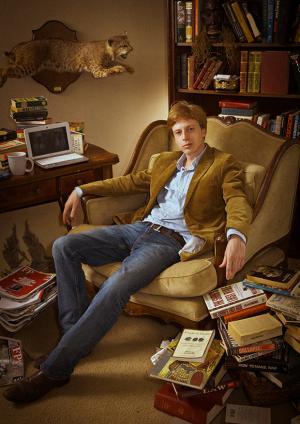

Brown’s satirical writing and razor-sharp political observations for magazines like Vanity Fair certainly helped build a following for the promising young journalist. It was Brown’s fearless and uncompromising scrutiny of firms such as Stratfor and HBGary, however, that earned him the most respect and support, including from the late firebrand reporter Michael Hastings.

Hastings, the Rolling Stone writer whose expose led to the resignation of U.S. Gen. Stanley McChrystal from the head military post in Afghanistan, inked a 2012 Buzzfeed piece on Brown’s arrest and was allegedly in the midst of a groundbreaking report before his tragic death on June 18 of this year, in which he may have included Brown as a source.

Why the Apparent Desperation?

The phrase “media gag order” in relation to United States v. Barrett Lancaster Brown is both too tame and slightly inaccurate, because the gag order is nothing less than the government’s attempt to restrict Brown’s free speech rights and impugn the professionalism of his highly-experienced defense team.

Indeed, it is just another part of an ongoing attack on Brown’s ability to speak out against those who wield power with impunity: first, the corrupt contractors he targeted, and now a government hell-bent on burying the young journalist and scaring off those who might take his place.

It is not only a violation of free speech rights: it is ham-handed and, as I will point out, needless, as there are mechanisms already in place to prevent or at least mitigate the government’s alleged concern that media coverage might derail any semblance of a “fair trial.” More on those mechanisms shortly.

On August 7, Assistant District Attorney Candina Heath filed a motion in Northern Texas’ Fifth Circuit court requesting that Judge Sam A. Lindsey, among other things, “instruct [the defense team] to refrain from making ‘any statement to members of any television, radio, newspaper, magazine, Internet (including, but not limited to, bloggers), or other media organizations about this case, other than matters of public record.”

Curiously, the prosecution makes a baseless, blanket accusation to bolster their not-so-humble request:

“Most of the publicity about Brown thus far contains gross fabrications and substantially false recitations of facts and law which may harm both the government and the defense during jury selection.”

They painstakingly proceed to detail every article either written by or about Brown since his pre-trial detention began, but fail to cite even one specific inaccuracy or “gross fabrication” that pisses them off – or, as they spin it, “might harm the jury selection process,” their purported motive for pushing a motion to gag trial participants.

There may be more at play here, however. Curiously, on July 16, the government filed a motion to “conditionally unseal” the sealed transcript of Brown’s September 2012 bail hearing for the purpose of defense team’s discovery.

Examining the document reveals that a protective order prohibits the release of this transcript to any party but the defense. The press and public, therefore, are kept in the dark about the precise allegations prosecutors made to deny Brown bail. Kevin Gallagher, the director of the advocacy group Free Barrett Brown, explained to me over email why the government may be keeping the proceedings under wraps:

“During a hearing after Barrett’s arrest, the prosecution alleged in support of the idea that he was a danger to the community and a risk of flight, that he’d been to Tunisia, where Anonymous had assisted the revolutions there. Barrett has been to Tanzania, but never Tunisia in his life. I think they are sealing things to cover up for careless mistakes and false allegations like that,” Gallagher attributed to a conversation with Brown’s mother.

So it is certainly not a stretch to assume that the government’s motion for a gag order is not just an attempt to control the public’s perception of Brown’s prosecution, but to cover up misconduct or prosecutorial mistakes. This then begs the question: what else might the prosecution want to bar from the press and public before and during Brown’s trial, which is set to begin in 2014?

Media Gag Orders: Unconstitutional and Unnecessary

Media Gag Orders: Unconstitutional and Unnecessary

The Supreme Court has not yet ruled on the constitutionality of gag orders on trial participants (i.e. lawyers and their parties), so as it now stands, lower courts are left to rule on them as they see fit.

What’s quite clear, however, is the fact that media gag orders are predicated on prior restraint and are undoubtedly content-based restrictions on speech. And on that notion, ladies and germs, the Court has ruled prior restraint unconstitutional, going so far as to state: “…prior restraints on speech…are the most serious and least tolerable infringement on First Amendment rights.”

The Supreme Court has ruled on gag orders placed solely on the press, and in 1976 it found in Nebraska Press Association v. Judge Hugh Stuart that court orders against pretrial publicity had to meet an exceedingly strict set of standards, chief among them being that if the numerous mechanisms in place to ensure impartial adjudication were insufficient, only then can a gag order strictly prohibiting media coverage proceed.

These safeguards, and thus alternatives, to gag orders have essentially been enshrined in our legal system since its inception. The measures include: changing a trial’s venue, postponing until public attention recedes, interrogating potential jurors “to screen out those with fixed opinions as to guilt or innocence,” sequestration, and jury instruction on what may and may not be used to reach a verdict.

The Nebraska Press ruling beautifully upheld, above all else, First Amendment protections like freedom of the press.

So what about gag orders that extend not just to the press, but to lawyers themselves, as in the case of Barrett Brown?

Professor Erwin Chemerinsky argues in his wonderful essay for the Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Journal that these protections must extend to trial participants. “The imposition of these gag orders is based on several assumptions that are, at the very least, unproven and more likely untenable,” he writes.

“First is the assumption that publicity jeopardizes a fair trial,” continues Chemerinsky, who cites numerous examples, including the cases of Rodney King, Reginald Denny, the Menendez brothers, and the O.J. Simpson prosecution, in which there was rampant speculation that press attention would all but seal the defendants’ fates. As we now know, publicity in these cases in fact had the opposite result. Flipping this around, it is difficult to see how pretrial publicity could endanger the government’s case against Brown.

“Second, even if publicity is detrimental to a fair trial,” he writes, “there is the assumption that statements by lawyers and parties cause or exacerbate the harm.”

Reviewing articles on Brown’s case already in the public sphere, it is difficult to see how Brown’s defense team has transgressed and endangered their client’s case. As for Brown himself, what has he really done except tell his side of the story, i.e. the truth as he sees it? The government has every right to tell their side.

And, actually, wouldn’t that be called a trial?

Attempting to prevent media coverage of proceedings doesn’t act as a repellant. The fruit fly behavior of the press means they will likely be drawn to “juicier” stories, particularly ones where the government appears to be hiding things, and gag orders may increase the likelihood that inaccurate information is disseminated to the public. When you cut off contact with “the most knowledgeable individuals, the attorneys and parties in a case, the media must accept off-the-record statements or second- and third-hand accounts,” Chemerinsky correctly notes.

It is the government’s burden to prove Barrett Brown guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, as it is to prove that violating First Amendment protections – in the face of built-in legal mechanisms, a defense team’s spotless ethical record, and press coverage that has done little more than publish what is already public record – is warranted.

To donate to Barrett Brown’s defense fund, visit http://freebarrettbrown.org/donate/.