Above: Image by Jim Cooke; photo via AP

On Ambassador Road, just off I-695 around the corner from the FBI, nearly 100 employees sit in a high-tech suite and wait for terrorists to attack Baltimore. They’ve waited 11 years. But they still have plenty of work to do, like using the intel community’s toys to target this week’s street protests.

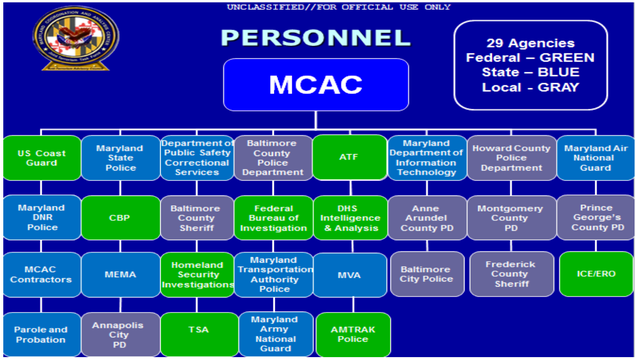

They are the keepers of the Maryland Coordination and Analysis Center, a government “fusion center” set up to share information and coordinate counterterrorist activities between 29 law enforcement agencies—federal, state, and local, including Baltimore city and county cops—in the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks. Seeded by a state anti-terror advisory council whose meetings are closed to the public, nourished by Republican and Democratic governors alike, MCAC has expanded its access to spying tools over the past decade and a half. It can pinpoint cellphone users. It can monitor movements of state motorists through their license plates, as it has done with an estimated 85 million drivers.

It turns out that Maryland hasn’t been under sustained assault from international terrorists, despite the wild fears of the homeland security boosters who seek to justify the center’s budget. So rather than accept the possibility that MCAC and other fusion centers were guarding against an overhyped threat, the federal government has expanded the mission to include threats that have always existed: When your job is to find bad guys, it makes it easier to define everyone as a bad guy.

The MCAC has adopted what the Department of Homeland Security calls an “all-crimes approach”—one focused not just on monitoring gangs and other criminal threats, but all manners of civil unrest, from Occupy protesters to the Baltimore residents who have clashed with police on the city streets this week. And it is run by a cop who has been accused of racism in the past.

“Twelve emergency support functions have been activated” in Maryland to address the violence in Baltimore, authorities told WBAL earlier this week, including “the Maryland Coordination and Analysis Center, which provides situational awareness and intelligence.” In fact, as protests over Freddie Gray’s death in police custody spread to other major cities across the country, MCAC and other fusion centers set up by DHS will be crucial to how local law enforcement agencies confront civil dissent.

From terrorism to tax-stamp fraud

Shortly after 9/11, then-Attorney General John Ashcroft ordered his U.S. Attorneys’ offices to set up district “Anti-Terrorism Advisory Councils.” The council for Maryland, led by a hard-charging Bush appointee, wasted no time in creating MCAC to coordinate the region’s terrorism response. It was given state-of-the-art tools, including “a 15-foot wide split television screen tuned into CNN, Fox News and a local news broadcast,” and office space to hold representatives of the FBI, ATF, DHS, Army, and Baltimore police, among others. In fact, one of the center’s early directors, Captain Charles Rapp, wore another surprising law enforcement hat, according to a 2007 profile in National Defense Magazine (emphasis added):

While there is no formal definition of what constitutes a fusion center, and no congressional mandate directing states to create them, DHS has disbursed $380 million in grants to help fund them so far, and their numbers are growing.

While the ultimate goal is to correct the well-documented mistakes that led to the 9/11 attacks, the centers are increasingly being used to track crimes not typically associated with terrorism, said Rapp, who also serves as the chief of the Baltimore Police Department.

By 2006, the greater Baltimore area had been identified by feds as a major drug-crimes target, and MCAC used its high-tech tools to pivot to fighting whatever crimes it could jam up under the guise of anti-terror and counter-narcotics:

A terrorist cell may be involved in other non-terror crimes to fund its activities. It’s the city cop, for example, who may enter an apartment on an unrelated call, and notice there is nothing inside but computers.

MCAC, and other fusion centers, are branching out to keep tabs on major crimes. Coupon fraud, evasion of state tax stamps on alcohol or cigarettes and identity theft, for example, can be used to fund plots. “You can’t really determine what type of crime is going to be related to terrorism,” Rapp said.

Our ‘Most Wanted’ page is most popular. Have you checked it out lately? http://t.co/88YvTxBawI

— MCAC (@MCAC_Alerts) April 21, 2015

“Geofencing” in evildoers

Nobody can say for sure what all of MCAC’s tech capabilities are—it exists to “fuse” a wide variety of intelligence collected by its constituent outfits. But the few that are known have wide applications. In 2012, Baltimore’s director of emergency management confirmed to Congress that area law enforcement could track suspects using their phones. With the help of DHS, he said, “We have developed cell phone tracking capabilities allowing law enforcement the ability to pinpoint the location of a specific cell phone, enhancing efforts to locate an individual.”

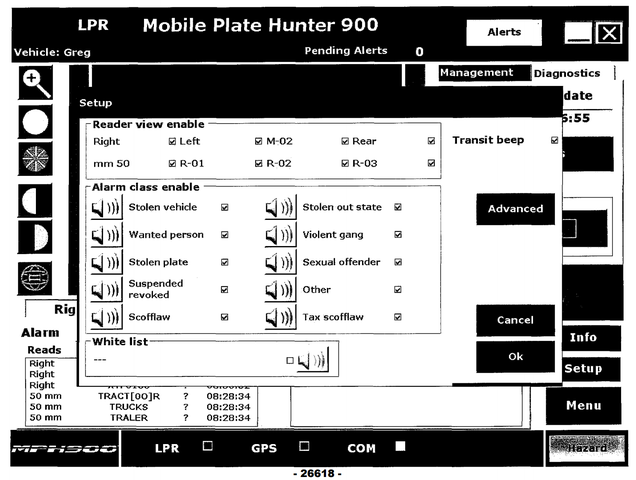

The most notable of MCAC’s intelligence has been a state-of-the-art license plate reading (LPR) system that has hoovered up motorists’ information and alarmed civil libertarians with its unprecedented speed. Maryland’s transportation chief, Marcus Brown, defends the system with an out-of-context quote by Thomas Jefferson—“information is the currency of democracy”—and adds:

In the event of a critical incident, the MCAC has the ability to enter the critical license plate information into the LPR central server. By doing this, anyone who is networked to the MCAC will automatically be notified if the vehicle in question passes by the LPR.

Those critical incidents aren’t confined to terrorism or even violent crimes: “Some states are using LPRs to collect taxes,” Brown reported. “Anything associated with the license can be used with the LPR.”

More recently, conservative libertarians have expressed fears that MCAC is using its LPR technology to track gun owners traveling through the state. John Filippidis, a Florida man with a concealed carry permit, was driving, unarmed, with his wife and daughters in the family SUV to a Christmas gathering in December 2013 when he was stopped by Maryland transportation police outside the Fort McHenry Tunnel in Baltimore:

Retreating to the space between the SUV and the unmarked car, the officer orders John to hook his thumbs behind his back and spread his feet. “You own a gun,” the officer says. “Where is it?”

“At home in my safe,” John answers.

“Don’t move,” says the officer.

Several hours later, after multiple police had unpacked and inspected his entire minivan, Filippidis was sent on his way with nothing but a warning. Maryland authorities have never revealed how they knew he owned a gun.

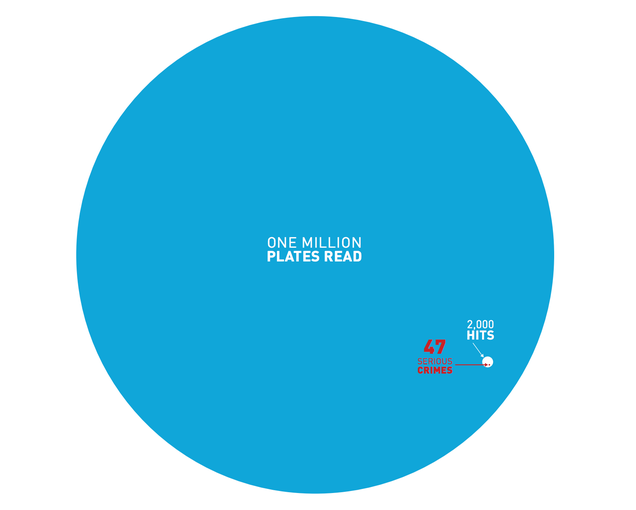

If you’ve been on I-95 in the Old Line State recently, chances are MCAC has your license plate on file, too; they keep all their info for a year, even if it isn’t linked to a crime. A 2013 ACLU study using MCAC data obtained under a FOIA request found that the fusion center had collected “more than 85 million license plate records in 2012 alone”:

According to statistics compiled by the fusion center for that year to date through May:

- Maryland’s system of license plate readers had over 29 million reads. Only 0.2 percent of those license plates, or about 1 in 500, were hits. That is, only 0.2 percent of reads were associated with any crime, wrongdoing, minor registration problem, or even suspicion of a problem.

- Of the 0.2 percent that were hits, 97 percent were for a suspended or revoked registration or a violation of Maryland’s Vehicle Emissions Inspection Program…

For every one million plates read in Maryland, only 47 were potentially associated with more serious crimes—a stolen vehicle or license plate, a wanted person, a violent gang or terrorist organization, a sex offender, or Maryland’s warrant-flagging program. Furthermore, even these 47 alerts may not have helped the police catch criminals or prevent crimes. While people on the violent gang, terrorist, and sex offender lists are under general suspicion, they are not necessarily wanted for any present wrongdoing.

Besides the potential chilling effect this kind of data collecting could have on drivers’ freedom of movement and other behavior, the report suggested that this license plate data could be used for more insidious “forms of crime analysis,” specifically geofencing: “Law enforcement or private companies can construct a virtual fence around a designated geographical area, to identify each vehicle entering that space.” Such tactics would have obvious appeal to police agencies seeking to limit the size and scope of street protests in Baltimore and elsewhere.

Targeting gangs, or something like them

More troubling than MCAC’s controversial license plate program has been its fuzzy focus on “gang” crime in Baltimore. Led by Rod Rosenstein, the Bush-appointed U.S. Attorney for Maryland who helped set up MCAC, the effort includes a “proactive component” that he says“involves not just waiting for dangerous criminals to get arrested, but actually going out to investigate them and develop cases against them and prosecute them and remove them from the community.”

Publicly, MCAC’s efforts show up in a “gang news” column that reports the latest arrests and rumors from inside Maryland; its most recent update was the Baltimore PD’s assertion that “they have received a ‘credible threat’ that rival gangs have teamed up to ‘take out’ law enforcement officers.”

MCAC’s public-facing intelligence on gang crime is equally superficial. In its most recent “public gang threat assessment,” the center reported: “Poverty and despair could be contributing factors of why juveniles join gangs.” The report added:

Law enforcement in Maryland has identified the following trends:

- Youth gangs using social media sites like Facebook®, Instagram®, Kik®, and Twitter® as tools to communicate, recruit, and threaten…

- Gang members commuting to other areas to participate in criminal activity.

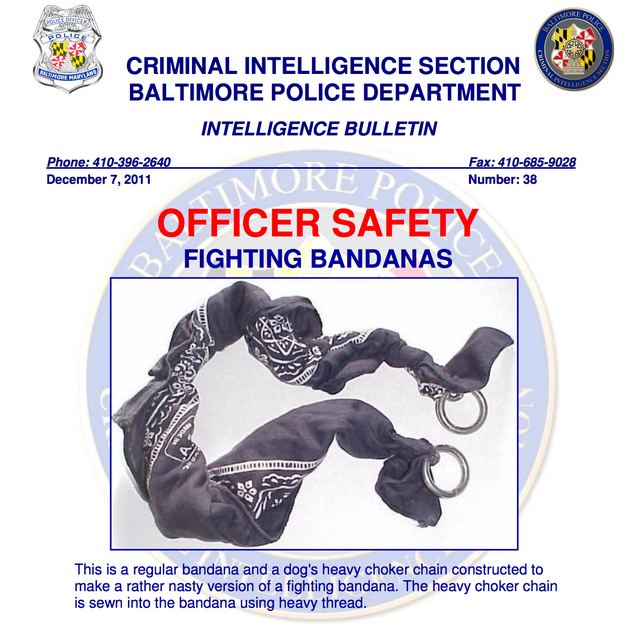

The center also puts out alarmist bulletins from its partner police organizations, such as one describing criminals’ alleged use of “trash bag bombs” and a 2011 warning that even bandanas can be used as weapons against officers:

MCAC has also expressed concerns that suspects are using publicly available police scanner apps and websites to listen in on law enforcement activities:

Further investigation revealed that the general public, as well as criminal gang members and associates, are utilizing the website www.radioreference.com to listen to law enforcement secure channels streaming via the Internet. Registration and access to the site is free… This situation presents a concern for officer safety.

More recently, MCAC has helped cohost an annual intel and law enforcement training conference with popular sessions like a seminar on “African-American Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs” and a workshop “on exploiting social media and the internet revealing the information investigators can obtain from it.”

All of these efforts are overseen by MCAC’s current director, David Engel, who previously ran the Baltimore police department’s intelligence unit—a unit that has been criticized “for sending undercover intelligence officers into public meetings to monitor debates,” the Baltimore Sunreported.

Engel’s time at MCAC has certainly been quieter than his tenure in the Baltimore PD, when a black female detective sued him for discrimination, alleging he’d demoted and transferred her because of her race. The 11-year veteran also charged that Engel had four other black detectives “transferred out of the unit for frivolous reasons and replaced by Caucasian detectives” in the half-year before her demotion, and he’d disciplined her for the same minor infraction that a white detective had committed without consequence. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission “determined that there was reasonable cause to believe that she was discriminated against,” but a federal court dismissed the charges.

Preoccupied with Occupiers

If the Baltimore center is using its assets to track and thwart protesters, it wouldn’t be the first time DHS’s network of fusion centers have done so. Last year, the New York Times documented the centers’ efforts to monitor Occupy protesters nationwide—surveilling their social media accounts, cracking their communications codes, and swapping tips to combat the protests, often with military assistance:

In many cases, law enforcement officials appeared to simply assemble or copy lists of protests or related activities, sometimes maintaining tallies of how many people might show up. They also noted appearances by prominent Occupy supporters and advised other officials about what — or whom — to watch for, according to the newly disclosed documents.

One of them, an intelligence research specialist working in the threat analysis center of the Pentagon Force Protection Agency, circulated an email describing Google searches as “a very handy intel gathering tool” to keep tabs on Occupy protests.

Documents obtained by the Times show that MCAC and the Baltimore city and county police departments assisted in these efforts to gather intelligence on Occupiers.

If all this sounds like a vast threat to privacy and civil liberties, the Department of Homeland Security agrees. In 2008, its privacy office issued a report that “identified a number of risks to privacy presented by the fusion center program.” Chief among these, it stated, were “threats to privacy associated with mission creep.”

Absent any terrorists to thwart, how exactly has the Baltimore fusion cell’s mission creep—from stopping 9/11s to monitoring protesters, drivers, and suspected gangbangers—extended to the street unrest that racked Charm City this week? No one’s saying: Emails and calls by Gawker to the Maryland Coordination and Analysis Center and its director all went unanswered.

[Image by Jim Cooke; photo via AP