Above photo: A barn sits in a field once worked by Charlie Utter’s cousin, a farmer who died by suicide in July 2017, Tuesday, March 3, 2020 in Georgetown, Ohio. [Joshua A. Bickel/Dispatch]

One by one, the three men from the same close-knit community took their own lives.

Their deaths spanned a two-year stretch starting in mid-2015 and shook the village of Georgetown, Ohio, about 40 miles southeast of Cincinnati.

All of the men were in their 50s and 60s.

All were farmers.

Heather Utter, whose husband’s cousin was the third to die by suicide, worries that her father could be next. The longtime dairy farmer, who for years struggled to keep his operation afloat, sold the last of his cows in January amid his declining health and dwindling finances. The decision crushed him.

“He’s done nothing but milk cows all his life,” said Utter, whose father declined to be interviewed.

“It was a big decision, a sad decision. But at what point do you say enough is enough?”

American farmers produce nearly all of the country’s food and contribute some $133 billion annually to the gross domestic product.

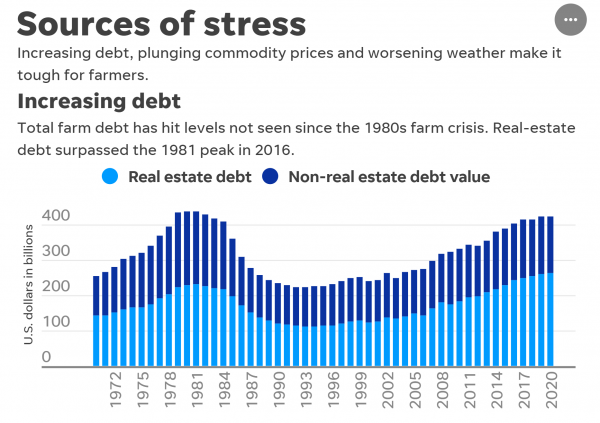

But U.S. farmers are saddled with near-record debt, declaring bankruptcy at rising rates and selling off their farms amid an uncertain future clouded by climate change and whipsawed by tariffs and bailouts.

For some, the burden is too much.

Farmers are among the most likely to die by suicide, compared with other occupations, according to a January study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The study also found that suicide rates overall had increased by 40% in less than two decades.

The problem has plagued agricultural communities across the nation, but perhaps nowhere more so than the Midwest, where extreme weather and falling prices have bludgeoned dairy and crop producers in recent years.

More than 450 farmers killed themselves across nine Midwestern states from 2014 to 2018, according to data collected by the USA TODAY Network and the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. The real total is likely to be higher because not every state provided suicide data for every year and some redacted portions of the data.

The deaths coincide with the near-doubling of calls to a crisis hotline operated by Farm Aid, a nonprofit agency whose mission is to help farmers keep their land. More than a thousand people dialed the number in 2018 alone, said spokeswoman Jennifer Fahy.

Even the $28 billion in federal aid provided by the Trump administration over two years wasn’t enough to erase the fallout from the trade war with China, many farmers said.

It’s not the first time that Washington’s efforts to help farmers have fallen short.

In 2008, Congress approved the Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network Act to provide behavioral health programs to agricultural workers via grants to states.

But it appropriated no money for the legislation until last year — more than one decade and hundreds of suicides later.

Some of the first four pilot programs awarded funding still have not seen any money.

“Farmers, ranchers and agriculture workers are experiencing severe stress and high rates of suicide,” said U.S. Sen. Tammy Baldwin, D-Wisconsin, who sponsored the bipartisan bill to fund the initiative. “Unfortunately, Washington has been slow to recognize the challenges that farmers are facing.”

Reporters spoke to more than two dozen farmers, mental health professionals and other experts across the Midwest who said the problem needs attention now.

Devastating economic events on their own do not cause suicides, experts said, but can be the last straw for a person already suffering from depression or under long-term stress.

“We like to identify something as the cause,” said Ted Matthews, a psychologist who works exclusively with farm families in Minnesota. “Right now, they talk about commodity prices being the cause, and it’s definitely a cause, but it is not the only one by any stretch.”

Case in point: After her family shuttered the dairy farm, Utter said, it relieved the immediate pressures — including those on her sister and brother-in-law, who helped milk her father’s cows daily despite their own full-time jobs.

But it created a different kind of stress for her father, said Utter, who serves as the Ohio Farm Bureau’s director for a four-county region including Georgetown.

It’s one felt by many farmers.

“When your farm doesn’t succeed or you have to sell off some property, not only are you letting you and your family down, you’re letting your family legacy down,” said Ty Higgins, spokesman for the Ohio Farm Bureau.

“‘My great-grandpa started this farm, and now I’m the one that’s causing it to cease?’ Boy that’s a tough thought. But a lot of farmers are going through that right now.”

‘It’s a problem now’

Farmers have been among the most at-risk populations for years.

More than 900 farmers died by suicide in five upper Midwest states during the 1980s farm crisis, the National Farm Medicine Center, found. During that crisis, mental-health counseling and suicide hotlines sprang up across the country. But after the crisis passed, the programs dried up.

The deaths subsided somewhat in the years that followed, but University of Iowa researchers found that farmers and other agricultural workers still had the highest suicide rate among all occupations from 1992 to 2010, the years they examined in a 2017 study.

Farmers and ranchers had a suicide rate that was, on average, 3.5 times that of the general population, the study found.

There are similarities between the 1980s farm crisis and the situation plaguing farmers today, said Brandi Janssen, a University of Iowa professor and director of Iowa’s Center for Agricultural Safety and Health. But the thinking around mental health has changed.

“I think it’s become more obvious to people,” she said. “Whether the rates or the numbers are higher or lower (compared with the 1980s), sometimes I don’t know if that matters. We know it’s a problem now.”

Federal, state and local governments must provide funding to help struggling farmers, said Janssen, but she cautioned that it will take more than just mental-health counseling and hotlines.

“It’s a lot more complicated than that,” she said. “It’s related to larger structures in the ag economy and climate and isolating work and rural areas that are being depopulated.”

Part of the problem, experts say, is that farmers are a tough bunch to reach – both geographically and emotionally.

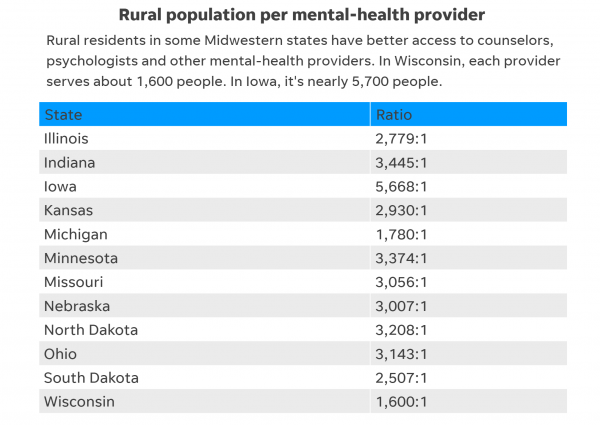

Most live in rural areas far from mental health professionals. Urban counties in the United States average 10 psychiatrists per 100,000 people, but rural counties have only three per that many people, a 2018 University of Michigan study found.

CARLIE PROCELL/USA TODAY NETWORK

Even when help is available, stigma prevents many in the largely male-dominated profession of farming from reaching out.

“In general, when men feel stressed, they pull back,” Matthews said.

Counselors have advised farmers to alleviate stress by finding a different job — something many find impossible to contemplate, said Fahy, the spokesperson for Farm Aid, which runs the crisis hotline whose calls jumped by 92% between 2013 and 2018.

“It’s essential,” Fahy said, “that farmers are talking to people that understand the unique aspects of agriculture.”

‘My heart hurts so bad’

Keith Gillie rarely slept or ate in the spring of 2017.

He was stressed about the family farm in Minnesota, which he and his wife, Theresia, bought from his grandfather in the 1980s. After pouring their lives into the operation, they found they couldn’t turn a profit anymore.

The couple talked about selling the farm and their equipment.

On the last Friday in April, Theresia reached out to her marketing manager and a loan officer to come up with a plan. But before she could finalize the details, Keith had taken his own life. He died by suicide the next day. He was 53.

“The day Keith died, part of me died, too,” she said. “Sometimes my heart hurts so bad that my whole body aches.”

Theresia ultimately sold the farm equipment but kept the property. She now operates the farm alone. And she speaks publicly about suicide. The Kittson County commissioner and former president of the Minnesota Soybean Growers Association has one goal in sharing her own experiences:

“I want growers to understand you’re not alone in this boat,” she said. “There’s others that are really struggling, too. And we’re going to find an avenue through this.”

At least 75 farmers died by suicide across six Midwestern states that same year, 2017, the USA TODAY Network’s data analysis shows.

An additional 76 farmers took their lives in 2018: Eighteen in Missouri. Eighteen in Kansas. Fifteen in Wisconsin. Thirteen in Illinois. Twelve in North Dakota.

But the trend started years earlier.

Keith Henneman of Grant County, Wisconsin, took his own life at age 29 after losing heifers to Johne’s disease in the mid-2000s.

Larry Ruhland killed himself on the Minnesota farm he operated with his wife, Barbara, in 2006 as they were working to renegotiate their contract to raise heifers for a local dairy.

“I didn’t put it together because I didn’t even think of the fact that Larry was under as much stress as he was under,” Barbara Ruhland said.

Matthews, the Minnesota farm psychologist, helped Ruhland through the turmoil after her husband’s suicide, and again when she lost a son to an aneurysm in 2014.

Too often, he said, he gets calls after the fact.

“It truly saddens me,” he said. “The person has committed suicide, and now I’m working with that family.”

It’s why training more people to spot the red flags of suicidal thinking is a crucial part of his mission. That includes anyone who interacts with farmers regularly: the ag management workers who set production goals, the auction folks who arrange the equipment sale, the bankers who deny the loan.

“That banker is at the kitchen table,” Ruhland said. “Those people are on the frontlines every day.”

Matthews, the Minnesota farm psychologist, helped Ruhland through the turmoil after her husband’s suicide, and again when she lost a son to an aneurysm in 2014.

“Farmers feel that they’re most helped by someone who understands them,” said Wisconsin state Rep. Joan Ballweg, a Republican from Markesan, chairwoman of the suicide prevention task force. “I’d like to see something that is dedicated (to farmers), like the national hotline number has a function for veterans.”

In Ohio, the state Department of Agriculture launched a campaign last year called “Got Your Back” to reduce stigma and encourage farmers to ask for help.They hand out cards with the Ohio State University Extension crisis line as well as the National Suicide Hotline and online resources.

“We want farmers to know that they are so much more valuable than their next crop,” said Higgins with the Ohio Farm Bureau.

Some programs host outreach efforts at events such as Nebraska’s Husker Harvest Days.

“Farmers are a tough bunch and they have thick skin and they don’t want to be seen pulling up to the counselor’s office,” said Susan Harris-Broomfield, the rural health, wellness and safety director at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. “That’s not their jam. However, we have one of the largest farm and ranch shows in the nation.”

She handed out wallet-sized cards with a help-line number and other resources — similar to those distributed in Ohio.

“We were actually surprised at how many of these, especially men – farmer men – were absolutely open to taking it and they thanked us for what we were doing,” Harris-Broomfield said.

Her biggest tip: Make the conversation about stress instead of mental health. Neither their booth sign nor a survey they handed out mentions mental health.

“Stress is something we can all relate to,” she said.

Stress mixes with grief in Georgetown, Ohio, where Heather Utter’s father is adjusting to life after farming, and her father-in-law farms 1,500 acres — a combination of the land he grew up on and the adjacent property that his cousin had tended until his death.

“If you don’t farm, you just don’t understand it,” Charlie Utter said of the stress and despair to which so many local farmers have succumbed. “There’s just so many ups and downs and variables you can’t control. It wears on you.”

Charlie Utter said he regrets not talking to his cousin sooner; he knew something was bothering him in the days before his death. Family members need to watch one another closely, he said.

“If you see somebody is down, go talk to them, and don’t put it off,” he said. “If people were more educated, it couldn’t hurt. One person might catch something.”

This story is a collaboration between the USA TODAY Network and the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. The Center is an independent, nonprofit newsroom based in Illinois offering investigative and enterprise coverage of agribusiness, Big Ag and related issues. Gannett is funding a fellowship at the center for expanded coverage of agribusiness and its impact on communities.