Above Photo: Doctors, particularly pediatricians, feel they can play an important role in explaining how climate change impacts health. Credit: Getty Images

As a source of information people trust, doctors believe they can help people understand that climate change is impacting health across the country right now.

Pediatrician Samantha Ahdoot may not use the words “climate change” when she’s talking to her patients and their parents in Alexandria, Va., but she’s talking about its impacts all the time.

Whether it’s a 6-year-old boy who contracted Lyme disease in November—long after ticks should be gone for the year—or having to start kids on spring allergy medication in February instead of March, climate change is making its way into Ahdoot’s exam room. And she’s not alone.

As a physician, Ahdoot practices at the intersection where public health and climate change meet. She is part of a group of physicians who announced on Wednesday the formation of the Medical Society Consortium on Climate & Health, which aims to help the public and policymakers understand how climate change is impacting health. The group represents more than half of the physicians in the country and includes 11 of the nation’s leading medical societies.

Climate change and public health

Dr. Samantha Ahdoot, a pediatrician in Alexandria, Va., sees patients with conditions exacerbated by climate change. Credit: Pediatric Associates of Alexandria

“When I discuss it, it’s very straightforward,” said Ahdoot. “The plants are blooming early because it’s so warm, and that’s why your child has allergies. Your child got Lyme disease in Chicago because it’s 60 degrees and the ticks are out.”

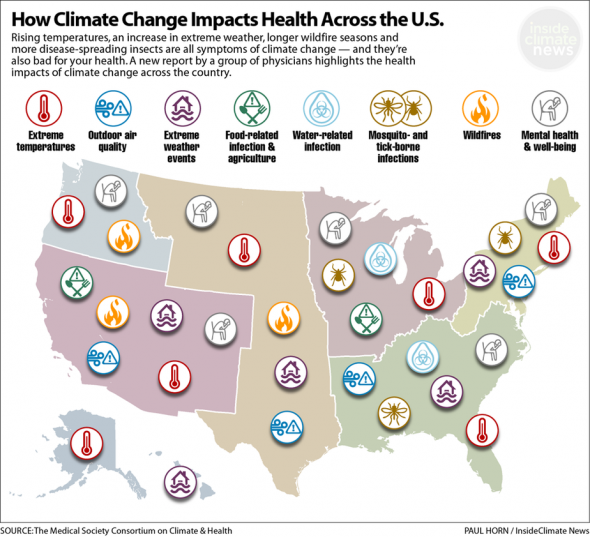

These are among the concrete health-related impacts of climate change—like an increase in stomach and intestinal illnesses following extreme weather events, or a 50 percent rise in emergency room visits for respiratory illness in areas impacted by the plumes of wildfires. A report released Wednesday by the consortium explores these and other impacts, highlighting the inescapable nature of climate change’s threat to health and the important role physicians play in getting the word out.

“It’s not just one part of the country, we’re hearing from physicians all over the country,” said Mona Sarfarty, the director of the consortium, who also directs the Program for Climate and Health in the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University. “The people suffering the most harm are kids, pregnant women and people with any kind of chronic condition, especially any kind of heart or lung condition.”

People inherently trust physicians and the consortium is hoping to leverage that trust to educate people about climate change. They believe they can play a role in helping people understand that 97 percent of the scientific community agrees on mankind’s role in climate change, that certain groups of Americans are more vulnerable to its health impacts right now, and that without immediate action, it’s going to get worse.

The formation of the consortium and the release of the report represents the first time that the disparate physicians groups, representing family doctors, pediatricians, obstetricians, allergists, geriatricians and internists, have banded together to publicly discuss how climate change is making Americans sick, Sarfaty said.

“There are certain areas of the country that aren’t experiencing this much,” she said. “That explains in part why it’s been easier in some places to ignore it. But physicians are seeing it everywhere. That’s why we have a need to speak out.”

Climate change’s role in health is easy to overlook. If you’re the parent of a teenager who fainted during soccer practice because of dehydration, it might be hard to see how that fits into the larger trend. But if you are treating that soccer player—and scores of others like her—you have a much different perspective.

In Billings, Mont., Lori and Robert Byron come into regular contact with the problem. Lori, 58, is a pediatrician. Her husband, Robert, 62, is an internist.

Lori Byron regularly treats children with asthma, a disease linked with climate change that grew to afflict 8.4 percent of the population in 2010, from 7.3 percent in 2001, according to the Centers for Disease Control. In 2014, 6.3 million children in the United States had asthma.

Physicians are on the front lines of climate change and public health

As doctors in Montana, Lori and Robert Byron treat the health impacts of climate change. Photo courtesy of Lori and Robert Byron

In Montana, wildfires are among the biggest environmental polluters. “Wildfire season is two and a half months longer now than what we used to have a few decades ago.” Byron said. “It definitely leads to more asthma attacks.”

When she sees families and hears about their summer vacation plans, she urges some to rethink where they’ll be going, because recent wildfires make the air unsafe for asthmatic kids.

Likewise, Robert Byron has to talk to his patients—many of whom have weakened lungs from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—about how climate change might be impacting them. It doesn’t always go well.

“Usually how I phrase it is that due to a combination of things like prolonged drought, increased insect infestation and the increased heat, a lot of the western forests are tinder boxes,” he said. He has run into occasional skepticism about the causes, but said they eventually land on the easily understandable concept that if its smoky, people will have more trouble breathing.

“It’s an area where [those of] us in primary care can take more steps with our patients in helping them understand that regardless of the cause, it’s putting your health at increased risk,” he said.