Finally, I bent over and picked a sprig of sage – whose ancestors in 1890 had been nourished by the blood of Red babies, ripped from their mothers dying grasp and bayonetted by the evil ones – As I washed myself with that sacred herb I became cold in my determination and cleansed of fear. I looked for Big Foot and YellowBird in the darkness and I said aloud —

“We are back my relations, we are home”. Hoka-Hey

–Carter Camp: Remembering Wounded Knee

On Feburary 27th, 2014 I was on Pine Ridge reservation for, Liberation Day, the anniversary of the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee. This was the 41st anniversary of the occupation and I stood outside of the Wounded Knee district school, holding a flyer for today’s“Four Directions Walk.” I stood with the northern part of the four directions. Three other walks from the east, west, and south were going to meet at Wounded Knee, the site of both the massacre of 1890 and the Occupation of 1973. I checked my GPS, “ten miles to Wounded Knee.” I stared at my feet. A member of the To’kala warrior society saw me staring at my brown hiking boots and suggested I bring a vehicle for our media team to rotate out of during the walk. The warrior walked off and joined other members of the warrior society. The men and women in camouflage talked amongst themselves, then spread out around the edges of the gathering people. I worried I’d be out of place with a vehicle, but saw a long convoy of cars,vans and trucks lining up behind everyone preparing for the walk. An elderly man pushed a walker between the children and teenagers gathered in front of the cars. The old man looked south towards Wounded Knee, placed the tennis balled walker in front of him, and pulled himself towards the site of the occupation. The school doors opened and children raced out and joined the walkers. A yellow school bus lined up in the convoy.

Some of the children ran onto the bus, then out, and took their place at the front of the walk, holding flags and staffs as they led us south to Wounded Knee.

We walked BIA road 28 and Vic Camp, an organizer for the event, walked beside me wearing a brown shirt with seven ribbons streaming in the wind, he pointed at the hills flanking the road. “My father lead the first warriors along these hills. We’re walking the way they first went in ’73.” I looked at the ridge of hills that flanked the road, and tried to imagine myself in that AIM and Ogala Lakota war party. “Is your father here?” I asked. Vic looked south and said that this was the first year his father wasn’t with them.

We walked a bit and I asked, “Why didn’t you call this a march? It says four directions walk on the flyer.”

“We’re not marching,” he said. “Today we walk. We walk together in prayer for those lost in 1890, and walk with our heads raised because of the occupation of ’73. We’re walking slowly with our families and children in prayer.”

We walked, and after five miles I’d already switched out of our media vehicle twice, but the kids in the front held their flags and staffs steady as they led the way. Vic walked beside me and looked towards the hills.

“This year’s different.” he said.

“What’s different?”

The colored flags snapped over the children.

“They’re leading us now. The children are the ones taking the flags and leading our people back to Wounded Knee.”

He wiped a hand across his face.

“They’re claiming their identities. They’re acknowledging their past and leading us into the future.”

“The occupation of ’73?”

“No, that’s the thing that let today happen.”

He walked off as we arrived at one of the four planned stops along the walk. The people circled while the To’kala’s formed a perimeter. Drums played as prayers and remembrances were shared. After ten minutes or so, the walk continued on and the To’kala’s formed around the edges as we progressed. I talked to a women as we walked. I pointed at the camouflaged men and women and asked if we were in danger.

The women said, “no, but it’s their duty to protect us. So they’re here.”

“So, they’re soldiers?”

“No, no, they’re warriors. Each of them was given the honor to protect their people and lands.”

I watched the warriors walk past us.

“So, they’re like police?”

She looked at me and shook her head.

“They’re part of the To’kala warrior society. Their traditions and ceremonies date back hundreds of years. I can’t tell you all of it in our walk, but know that they’re reclaiming their warrior ways as well. Those children claim themselves, and these young men and women do as well.”

We grew closer to Wounded Knee and she approached me again.

“Did someone tell you who you are,” she asked.

“Well, no, I don’t think so.”

“Our people lived through that. Through being told who we were. Through forced religion, forced education, forced assimilation every day we were told who we were to the beat of teachers fists. There was no room for our culture in the time of boarding schools.”

“But here you are?”

She nodded. “These children don’t know that reality.”

She pulled me aside.

“Do you know how a people keep their culture and traditions when the mighty United States Government decides to try to eliminate them?”

A group of horses trotted past.

“I don’t know.”

“You resist. We resisted that garbage. The sexual assaults. The killings. We resisted it all and we made it. We are here. And because of that every Lakota has that in them. Resistance. Resistance is part of the Lakota identity.”

She started to walk away, and then came back.

“My mother was a red supremacist. She hated white people. I’m not like that, but, my mother had every right. If you knew all the things that white people did to her and our people in their boarding schools. You’d understand why she hated them. Today, we need to come together.”

I didn’t know enough about boarding schools to understand this, but the boarding schools would later be explained to me by an elderly woman missing her front teeth. We were in a small trailer heated by a wood stove. The woman sat next to a younger woman. Twenty or so men stood silently around them listening.

The old woman cleared her throat, “They used to beat me in school as a girl.” she said–everyone leaned in. “The teachers, the nuns, they asked me questions. I answered them.” The old women smiled. “I answered them in my first language Lakota.” She slapped the back of her hand. Slap. Slap. Slap. “Their rulers hit hard! I went home with the back of my hands bloody.” She took a deep breath. “My father he said, what’s wrong!? What’s wrong?! Why are you crying?” The old woman leans forward as the people try to cram closer. “I told them! I don’t know? They hit me when I speak Lakota. I don’t know why?” She looked around at the gathered people. “He told me to lie to save myself the pain and say I didn’t know the language.” Her chair creaked. “So I did. I lied, and any time someone spoke to me in Lakota. I said I didn’t know it. I hid my first tongue for years….to save myself from their beatings.” She smiled a huge toothless grin. “Then! In ’73! because of those people who came and occupied Wounded Knee.”

She took a deep breath,

“I could speak my language again.” She rocked forward, “I could speak Lakota! That’s what Liberation Day is, it’s the day I could speak again.”

Everyone in the room exhaled, and I’m back in front of my computer trying to tell you about my walk to Wounded Knee for Liberation Day. Liberation Day can’t be found in the words provided here, but in the feeling in the air as hundreds of people meet from the four directions. They come together led by Lakota children who hold in their hands, flags, and medicine staffs they’ve carried ten miles to the top of a small mound called Wounded Knee. Under their feet sits soil soaked with the blood of their ancestors who were massacred despite the promise of peace from the United States. Who after murdering the Lakota, forced them into schools and terrorized them for practicing their traditional ways. Under their feet vibrates the memory of the people who came back to make a stand against cultural annihilation.

———————————————————————————————

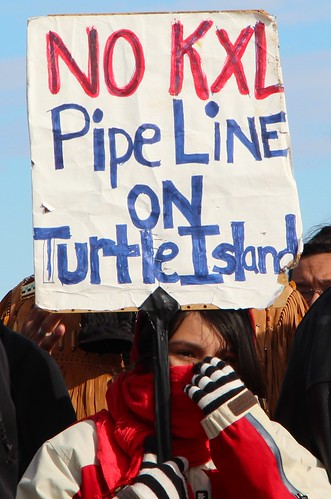

The night after the walk we all gathered in the local elementary school for a feed to commemorate Carter Camp’s life. I sat and spoke to Vic about resistance, and the Lakota identity. He said that right now the battle is for the water. That pipelines like the Keystone XL are threatening their way of life.

“You know that we’re indigenous peoples. We’re of the land. It’s our duty to protect our mother. And Earth, she’s weeping right now.”

The drums shook the floorboards as people waited in line for their bowl of buffalo soup. The gym had “Warriors” in big red letters on the wall.

He leaned close to me.

“We’re the biggest threat to the United States Government. You know why?”

The people sat in bleachers eating and laughing. I shook my head.

“Because, we have another way to see the world,” he points east, “Out there, they only see the world through a financial lens. And that’s all they know. One way to see the world.”

He shrugged.

“They think they’re free, but that’s not freedom. We’re free because we know there’s another way to live, and that’s why we’re dangerous.”

He flattened his palms on the table and pushed himself up.

The line for food was gone and the veterans of Wound Knee were asked to take the center of the gym. Drummers played and people filed around to shake the veterans hands and embrace them. An old hunched veteran shook the hand of a woman forty years his junior. She carried an infant on her shoulder. The veteran shook the woman’s hand in both of his and looked up at the baby. The Wounded Knee veteran reached his arms up, cradled the babies hands in his own, and shook them as well.