Above Photo: From Fairworldproject.org

Once again, Brazilian labor inspectors have found slave labor1 on plantations where Starbucks buys coffee. And not just any plantations, but ones that have been “certified” to Starbucks’ C.A.F.E. Practices standards. This marks the second time in nine months that this has happened, pointing to a huge systemic problem with the way Starbucks is meeting their commitment to “99% ethical coffee.” It’s time for that to change.

STARBUCKS COFFEE ON THE “DIRTY LIST”

How do we even know that this is happening? The Brazilian government has taken steps to address forced labor throughout their farming and manufacturing sectors. One of those steps is publishing an annual “Dirty List” of those found in violation of Brazilian law and what they have defined as modern slavery: forced labor, debt bondage, dangerous and degrading conditions, and debilitating work days.

In the fall of 2018, local labor inspectors published reports tying Starbucks to a plantation where workers were forced to work live and work in filthy conditions. Workers reported dead bats and mice in their food, no sanitation systems, and work days that stretched from 6AM to 11PM. Workers reported that the payment system was rigged and the coffee they picked disappeared before it could be tallied. Deductions to cash their checks meant that workers had barely any take-home pay. While the plantation carried Starbucks’ C.A.F.E. Practices certification, Starbucks denied buying from the farm in recent years (C.A.F.E. Practices allow for inspections to happen as infrequently as 2-3 years, depending on several factors including previous inspection scores).

In the more recent case, labor inspectors found workers in similarly dire conditions on another plantation certified to Starbucks’ standards. Overall, the Brazilian labor ministry reports that workers toiling in slavery-like working conditions was at a 15-year high in 2018.

Clearly, there’s a problem. And Starbucks’ C.A.F.E. Practices program is not equal to solving it—or even to bringing the problem to light. It is not their own transparency efforts but those of the Brazilian state that revealed the issues on these farms.

STARBUCKS C.A.F.E. PRACTICES – WEAK IN THEORY AND IN PRACTICE

To understand the failings of Starbucks’ C.A.F.E. Practices program, first a little history. For two decades, advocates have pressured the world’s biggest coffee shop chain to clean up their supply chains. For years, despite calls to commit to fair trade, Starbucks’ commitment lagged. Fair trade purchases peaked in 2014 at 8.6% of coffee. Instead, Starbucks launched their own Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) code, C.A.F.E. Practices. And in 2015, Starbucks was able to claim that 99% of their coffee was “ethically sourced” in compliance with those standards.

If a company makes barely any progress on an ethical commitment for over a decade and then rewrites the standards and checks off the goal—that seems suspect, right? Ultimately, Starbucks C.A.F.E. Practices standards allowed them to change the finish line and get activists off their backs. That shiny ethical veneer is significantly watered down from the fair trade commitment they couldn’t make:

- C.A.F.E. Practices standards have no minimum guaranteed price.

- While fair trade standards require coffee to be grown by small-scale farmers organized in cooperatives, there is no such requirement for C.A.F.E. Practices.

- Finally, fair trade standards set the stage for farmer-led community development. Democratically administered premium funds mean that those communities get to decide how to invest in their own communities.

Further, labor advocates (and our own Justice in the Fields report) have emphasized that an annual inspection is inadequate to ensure that workers are protected on plantations and large farms. C.A.F.E. Practices standards allow farms to be inspected every 2-3 years (depending on several factors, including previous scores). Such a system is in no way equipped to protect workers—or meet its own claims of “ethical” practices.

These three points are just a few ways that C.A.F.E. Practices standards differ from fair trade, but they get to the heart of the issue: Is the goal to change the system of trade or to make someone feel good about their cup of coffee?

This sort of top-down CSR program is fundamentally not set up to address the issues that lead to workers laboring in slavery-like conditions on coffee farms. And that’s in large part because they are structural issues—the system is built on exactly these practices.

SUPPORT SMALL-SCALE FARMERS, END THE CYCLE OF EXPLOITATION

80% of coffee is grown by small-scale farmers, an estimated 25 million of them around the globe. Brazil, however, has a long history of large-scale coffee production. In the early 1800s, landowners built vast plantations, expanding their production on the backs of thousands of enslaved people brought from Africa. Even after slavery was abolished in the late 1880s, the same imbalance of power remains with a few landowners controlling huge amounts of land and many, many more people left landless and exploited for their labor. Brazil is not unique in this. Indeed, large-scale plantation model agriculture throughout the Americas is built on this model.

And thus, when we advocate for the industry to support small-scale farmers and fair trade, it is not merely about doing better corporate social responsibility. Large-scale plantations have amassed their land and market dominance through a sustained history of theft. To call on Starbucks to support small-scale farmers is to demand that they do their part to shift this system rooted in exploitation. With minimum prices and premium funds that are democratically controlled by farmers and their cooperatives, fair trade offers a model to do this (when defined by the terms of a strong, farmer-controlled certification such as Fairtrade International or SPP).

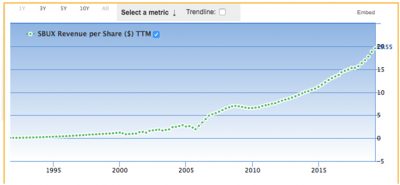

COFFEE FARMERS ARE IN CRISIS WHILE STARBUCKS’ PROFITS INCREASE

The call for change is particularly urgent in 2019. Commodity market prices are hovering between $0.90-$1.00 per pound for green, unroasted coffee. Farmers are earning the same amount for their crop now as they did 20 years ago (or less, when you consider the increased cost of production). The low prices are creating a crisis in coffee, as detailed in an earlier post. Meanwhile, Starbucks gross profit has gone steadily up.

A Catholic Relief Services report on labor conditions in Brazil’s coffee sector notes, “At [$1.00/pound], few growers can afford to comply with the minimum that is required of them by law, to say nothing of the reinvestment necessary to stabilize labor supply and foster farmworker empowerment.”2 Forced labor and slavery-like conditions are not the problem of a few bad apples. They are the result of a system that has historically extracted all it can from farmers and workers in the interest of profit.

FAIR TRADE HAS POTENTIAL TO IMPROVE FARMERS’ LIVELIHOODS

Meanwhile, fair trade farmers have the potential to fare better. Fairtrade International sets a minimum price for coffee of at least $1.60 per pound for conventional and at least $1.90 per pound for organic. Farmer-led SPP (Simbolo Pequeno Productores, or Small Producers Symbol) sets their minimum at $2.20. Both are working to move the conversation around price away from minimums and towards addressing living incomes for farmers. It is not clear how much Starbucks currently pays for their coffee. Their last published report, in 2011, cited $2.38 per pound—about the same as the ever-volatile commodity market, which was hitting 14-year highs and hovering around $2.40 per pound. Since that time, their sustainability reporting has not included prices paid per pound.

Price per pound is one key issue. But the other component of farm income is volume. If a farmer is only able to sell a fraction of their crop at that higher price, the overall impact is diluted. Put another way, 72% of coffee from fair trade cooperatives gets sold outside the fair trade market. There is plenty of coffee from farmers who have already gone through the work of getting certified. The only thing they need are buyers willing to commit to fair trade terms.

It’s high time for Starbucks to drop the pretense of “99% ethical” and commit to real fair trade and small-scale farmers. Let Starbucks know that you don’t want slave labor to fill your cup: Send them an email here.

1 Brazilian Article 149 identifies four elements as constitutive of conditions analogous to slavery:

- Forced labor: people forced to work under threats/acts of physical or mental violence.

- Debilitating workdays: workers subjected to workdays that go far beyond normal overtime and threaten their physical integrity.

- Degrading conditions: people lodged in substandard housing and/or without access to personal protective equipment, decent food or water at the work fronts.

- Debt bondage: workers are tied to labor intermediaries and/or landowners by illegal debts related to expenses on transportation, food, lodging and work equipment.