Above: Labor groups push for ‘just transition’ in March for Climate Justice. From Sentro

For over forty years we have known that avoiding disastrous climate change requires breaking fossil fuels’ hold on our economy and way of life. Yet, throughout all that time, debate, negotiations, and actions have fallen short in triggering, never mind managing, an energy transition. At this pivotal moment, those considered climate leaders are just not going far enough. Even California, the United States’ “climate heavy-hitter” (but also top oil producer), seems to be unable to pursue a key climate action within its boundaries: ending the leasing of new oil fields. Instead of addressing the drivers of climate change head-on, we just nip at the system’s edges.

Real climate leadership means taking on the root causes of climate change and other societal ills to change the system before we breach critical thresholds in temperature rises. Within the system we have, we will never be able to push the needle far or fast enough toward a renewable energy system. We need to start implementing energy interventions today in key points of the system with the aims of keeping fossil fuels in the ground, deploying renewable energy, and changing our political economy.

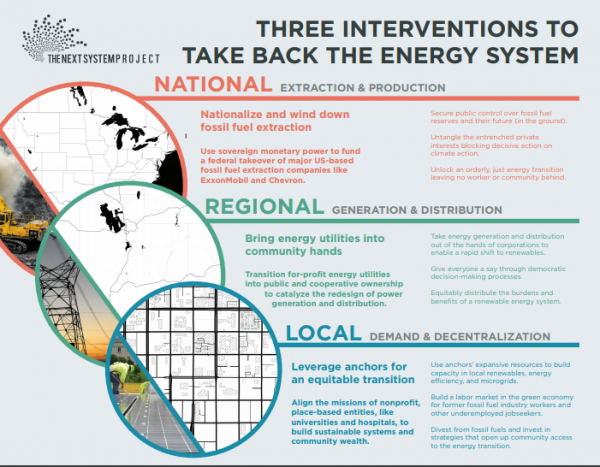

Three groundbreaking and complementary interventions could start transforming the power structures that promote and enable our problematic energy and political economic systems: quantitative easing for the planet, public ownership for energy democracy, and anchor strategies for the energy transition. By proposing interventions at all governance levels—federal, regional, and local—and aiming different points of the energy chain, these interventions combined can bring us closer to an system on common ground with sustainability, democracy and equitability.

The Green Transition and the Next System

When the Global Climate Action Summit convenes in San Francisco on September 12, 2018, one goal will be to affirm that the world beyond the Trumpian miasma is “still in” the Paris Accords. But the Summit seeks also to “demonstrate that stronger commitments are necessary, desirable and achievable.”

This convening is commendable and very important. It is also an opportunity for we, the people, to be crystal clear about what we expect of those in power: these “stronger commitments” must at long last be commitments to actions fully responsive to the desperate situation the world now confronts.

Many climate scientists and others have reached the conclusion that, because we have dithered so long, we now face the prospect of both extreme impacts from global warming and ocean acidification and, eventually, extreme rates of emission reduction. Every year of more procrastination makes both more difficult.

The Systemic Roadblocks to Climate Action

The challenge of mounting an adequate response to climate change has to be understood within the context of the larger systemic crisis facing the United States. The 1972 Limits to Growth, published when environmental movements were forming in this country, emphatically explained that our economic system was incompatible in the long term with the health and productivity of our finite planet. As the ecological rift widens, we must recognize the incompatibility of three interconnected imperatives of the current system that both push us toward climate catastrophe and prevent meaningful action—the unrelenting pressure for economic growth, the outsized power of corporations, and the United States’ extractive approach to resource use.

Quantitative Easing for the Planet

Keeping Carbon in the Ground & Dissolving Climate Opposition

Across the political spectrum, conventional wisdom holds that technology and finance remain the greatest obstacles to moving society beyond fossil fuel dependency. Yet, neither is the real reason why progress on climate action has stalled for decades. Solar applications alone have the technical potential to provide 100 times more electricity than the United States currently consumes, as concluded by the Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory in 2012.1 In the world’s richest nation, the same one that created trillions of dollars to save banks between 2008 and 2014, financing is not the problem either.2 The United States can wield its sovereign monetary power to finance and encourage investment in non-extractive energy projects. Why, then, do oil and gas companies still seek new reserves, governments still license dangerous infrastructure, banks still finance carbon-intensive projects, and investors still embrace fossil fuel companies?

The short answer is that our government has no interest in going after the fossil fuel industry, the source of the climate mess. Call it dependency on corporations to sustain a “healthy” economy or call it pure political oligarchy, the reality is that governments bend over backward to help this industry.

Public Ownership for Energy Democracy

Opportunities for publicly-run energy utilities to revolutionize generation and the grid

Energy democracy—a new idea from the ranks of community organizers, labor, and renewable energy advocates who see our current energy system as broken and destructive—seeks to take on the political and economic change needed to tackle the energy transition holistically. A democratic energy system powered by renewables (and free of fossil fuels) would distribute wealth, power, and decision-making equitably. But, practically speaking: How can we redesign our energy system with energy democracy at its core?

A first step is to stop exploiting fossil fuel reserves, as Quantitative Easing for the Planet proposes. Another imperative is to shift ownership of the generation, transportation, and distribution of energy. Restructuring and democratizing our electric systems through public ownership—whether government or cooperative—can help transition the United States away from fossil fuel production and toward a renewable future built with communities in mind instead of profits.

An Anchor Strategy for the Energy Transition

Leveraging anchor institutions’ power to build a local, sustainable, and inclusive energy system

While many cities and communities rely on a “smokestack chasing” approach to economic development, others are starting to focus on a new approach to economic development that centers people and place. Instead of measuring growth by just revenue, this approach, coined “community wealth-building,” strengthens the local economy through broader democratic ownership and control of business and jobs.1 Rather than relying on (foreign) corporations to bring economic development to a region, community wealth building works to cultivate existing, local assets. Often, this includes working with anchor institutions, public and nonprofit entities rooted in place, such as hospitals, universities, cultural organizations, and local governments.2 It can be a night and day difference. As PolicyLink’s Tracey Ross explains, “General Motors in Flint, Michigan, picked up and left. And with it went all of these jobs, and that really decimated the economy. Wayne State University in Detroit? They’re not going to be picking up and leaving.”3

These large and economically vital entities are often driven by a broader mission than maximizing profits. For example, a non-profit or public hospital’s main goal is to promote long-term health and well-being in the communities it serves. Similarly, most universities aim to provide education to foster people’s productive and civic capacities. Given their social missions, invested capital, and relationships to customers, employees, and vendors, these institutions are rooted in communities for the long run, and as such, don’t have the same knee-jerk reaction as for-profit industries to fluctuating economic conditions. What’s more, they often have a responsibility to their community as custodians of significant public resources in the form of tax exemptions or, in the case of public universities and hospitals, government grants.

James Gustave “Gus” Speth is Senior Fellow and co-chair of the Next System Project at the Democracy Collaborative. In 2009 he completed his decade-long tenure as Dean, Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, and joined the Vermont Law School in 2010. From 1993 to 1999, Gus Speth was Administrator of the United Nations Development Programme and chair of the UN Development Group.

Carla Skandier joined The Democracy Collaborative as a Research Associate with The Next System Project in 2015. She is a Brazilian attorney and holds a LL.M. in Energy Law and Policy and a Certificate in Climate Law from Vermont Law School. Carla’s work focuses on addressing climate change through systemic solutions.

Johanna joins the Democracy Collaborative as a Master’s student of sustainable innovation at Utrecht University. Her research focuses on energy democracy and the just transition away from the fossil fuel economy. She has worked on climate both in the United States and the Netherlands. Most recently, she worked on divestment campaigns for pension funds, universities, and cultural institutions alongside groups such as Fossil Free NL and BothENDS.