Above: A US soldier walks around the rubble of Hamhung, North Korea, in an undated photo. Carpet bombing by the United States reduced North Korea to rubble.

DOMESTIC AGENDA SACRIFICED TO THE KOREAN WAR THAT TESTS CHINA

The Korean War further bound organized labor to the ruling order on racist grounds. Military tensions between communist and capitalist blocs escalated with the prospects of an inevitable German and Japanese surrender, the expansion of Soviet influence, the probability of a communist victory in China, and the perceived need of the Anglo-American plutocracy to restore German and Japanese economies as anti-communist bulwarks regardless of moral cost.

In 1944, Washington unilaterally decided that Japan would run the Korean economy after the war. Five days before Japan formally surrendered military control of Korea to the United States, and just after Soviet forces entered the war against Japan on August 8 as Stalin had pledged to do at Yalta, U.S. military officers engineered a formal division of the country.[1]

Forty years earlier, President Theodore Roosevelt had given Korea to Japan in return for Tokyo’s acceptance of the U.S. conquest of the Philippines. Both Washington and London hoped to steer Japan toward Korea and Manchuria and away from the Philippines and Britain’s Asian colonies in Burma, Malaya and Singapore. This foreign policy strategy was designed to thwart the interests of Germany and Russia in Asia. It allowed Japan to strip Korea of its resources and its women of their dignity, as they compelled hundreds of thousands of Koreans to submit to the Japanese army as “comfort women, while over six million Korean men served in slave battalions.”[2]

On August 14, 1945, Rockefeller employee Captain John J. McCloy, head of the State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee (SWNCC) and “Chairman of the American Establishment,” directed two young colonels, Dean Rusk and Charles Hartwell Bonesteel, to enter a room and map out Korea’s division, despite majority Korean opposition. Curator of Anthropology for Yale’s Peabody Museum, Cornelius Osgood, “an experienced observor of Korea,” concluded in a confidential report to the Secretary of the Army that Koreans “would never support a separatist policy.” Cumings drew a historical analogy: “No Korean accepted the division as permanent in 1950, just as no American in the civil war years of the 1860s would have accepted a foreign policy decision to divide the United States five years earlier.”[3]

Caucasians Rusk and Bonesteel decided otherwise, and settled on the 38th parallel, even though they felt that the Soviets might protest a line drawn too far north. Stalin said nothing. On September 9th, the first US military detachment consisting of eight officers and ten enlisted men arrived. They met with their Japanese counterparts who formally surrendered to American Lt. General John Reed Hodge. No Korean was allowed to witness the formal ceremony.

A week later, the communist Korean People’s Army (KPA) formed in Seoul, South Korea. It established peasant associations and labor unions, with two-thirds of its ranks drawn from the peasantry and one-fifth from the proletariat. With respect to the North Korean Workers Party, a 1949 U.S. military top-secret study of 1,881 “cultural cadres” found that 66% came from the poor peasantry while 19% were proletarians. On September 19, Korean-born communist Kim Il Sung, an “anti-Japanese patriot” son of religiously devout Protestants, returned to his native land, battle-hardened from fighting the Japanese in Manchuria since 1932. Within six months in 1946, 4.2 million peasants received land in North Korea.[4]

In 1945, Colonel M. Preston Goodfellow personally arranged for Syngman Rhee to return from the U.S. Rhee possessed impeccable academic credentials. He graduated from George Washington University (BA 1907) and Harvard University (MA 1908). He was the first Korean to receive a PhD from a U.S. university (Princeton 1910). Goodfellow, OSS deputy director with a personal stake in Korean gold and tungsten mines, helped establish a separate southern government in 1945 and 1946. Most importantly, as Rhee’s military advisor, Goodfellow choreographed border clashes and the early stages of the Korean War. [5]

Rhee behaved as if the brutal Japanese occupation had never ended. Cumings noted, “The absence during the Occupation of any serious removals of Koreans who served the Japanese meant, of course, the perpetuation of a colonized elite in every walk of South Korean life. Rhee reinforced and protected pro-Japanese elements, especially in the police and the military, something he sought to camouflage with noisy bluster against the Japanese.” [6]

Lt. General Hodge formed a full-fledged military government in South Korea, though he initially lacked any kind of international mandate. He had to accept Rhee, despite suspecting him of planning a military coup on his own: “Rhee … is guilty of a heinous conspiracy against American efforts … I have real dope Rhee in deep.” Many times, Hodge was on the verge of arresting him for corruption and assassinations of political opponents, but held off because there was no viable alternative that would not be pro-communist. This Korean police state could not have survived a day without massive U.S. support. [7]

H. Merrell Benninghoff, State Department political adviser to General Hodge, dispatched the following communiqué to Washington:

Southern Korea can best be described as a powder keg ready to explode at the application of a spark. There is great disappointment that immediate independence and sweeping out the Japanese did not eventuate. [Those Koreans who] achieve high rank under the Japanese are considered pro-Japanese and are hated almost as much as their masters. … All groups seem to have the common idea of seizing Japanese property, ejecting the Japanese from Korea, and achieving immediate independence. [8]

In secret reports, CIA recognized the lack of “ articulate proponents of capitalism among the Koreans.” Indeed, CIA’s stable of sociologists came to the researched conclusion that Korea was in the hands of a “grass-roots independence movement which found expression in the establishment of the People’s Committees throughout Korea in August 1945.” [9]

Major General Albert Brown profiled those who held formal state power:

The most powerful group in [south] Korea today is the rightist group. Their power derives from the fact that they control most of the wealth in Korea. They occupy strategic positions in government both at Headquarters and in the field, as well as in police. To a large extent they have the power to dictate policy for control of Korea. [10]

Washington financed right-wing forces that sponsored anti-Soviet demonstrations, but such efforts garnered no wider popular support, if only because the Soviets had “no involvement with the Southern partisans.” Cumings reports, “the foreign model that has been more influential on Kim Il Sung, since the 1930s, has been the Chinese. Since the experience of the Korean war, Kim Il Sung has hated the Soviets. …Its leaders [Korean communists] were hard bitten guerrillas … steely and determined people whom the Soviets could not impose effective controls upon, except in the fantasies of Western scholarship.”

The domestic need for increased military expenditure at the sacrifice of free health care for every American compelled Washington “during the Korean War to view China and North Korea as tools of Moscow,” even though the last two Soviet army divisions had been withdrawn from Korea in 1948. The British Foreign Office differed with Washington’s interpretation. R.S. Milward portrayed Kim Il Sung as a Korean Tito.[11]

Racism suffused Washington’s strategic planning based upon the assumption of innate Caucasian —and especially Anglo-Saxon—superiority over “the Oriental.” In March 1950, Hong Kong’s U.S. Consul Everett Drumwright marveled that North Korean industrial plans were so “remarkably lucid, consistent and well organized … so well prepared as to suggest they were written by Soviet `advisors.’” He judged the DPRK to be “merely an instrument of Soviet control.” Senator Ebert Thomas of Utah defended Japanese reforestation of Korea as “one of the great things in history,” even if they “had to shoot [Koreans] to let the trees grow.” Mayflower descendent Senator Henry Cabot Lodge summed up Korea: “It isn’t much good, but it’s ours.” New York Times military editor (1937-1968) Hanson Baldwin demonized Koreans:

We are facing an army of barbarians in Korea … as reckless of life … as the hordes of Genghis Khan …They have taken a leaf from the Nazi book of blitzkrieg … Mongolians, Soviet Asiatics and a variety of races … the most primitive of peoples …

[To the Korean] life is cheap. Behind him stand the hordes of Asia. Ahead of him lies the hope of loot [that] brings him shrieking on…[12]

The chief counsel of the Nuremberg Trials echoed Baldwin. Brigadier General Telford Taylor wrote, “The traditions and practices of warfare in the Orient are not identical with those that have developed in the Occident …individual lives are not valued so highly in Eastern mores. And it is totally unrealistic of us to expect the individual Korean soldier … to follow our most elevated precepts of warfare.” Five-star general Douglas MacArthur mused, “`the Oriental dies stoically because he thinks of death as the beginning of life’ (utterly baseless in the secular Korean context); `the Oriental when dying folds his arms as a dove does his wings.’” Four-star General Matthew Bunker Ridgway wrote to General J. Lawton Collins of the Joint Chiefs of Staff that the “evil genius” was “some type of Eastern mind and whether Russian or Chinese, we shall inevitably find many of the same methods applied on major scales, if and when we confront the Slav in battle.”[13]

U.S. political and business leaders hoped for a share of a Korean gold or tungsten mine. John Staggers, U.S. investor in Korean gold mines, suggested the following scenario: “Let’s get this Government [sic] recognized then let the Korean people in the South take care of [the communist] problem …forget about the Russians … [recognize the South] … Then we will take care of the northern situation.” [14]

Staggers followed the lead of Herbert Hoover, William Randolph Hearst, J. Sloat Fassett, Ogden Mills, and J.B. Haggin who had with the acquiescence of Japanese occupation forces achieved controlling interests in Korean gold mines where the best prospects lay north of the thirty-eighth parallel. [15] Haggin and “Wild Bill” Donovan teamed up to found the American Legion.

Fassett had a stake in Chinese gold mines. He married into the San Francisco Croker family that had a controlling interest in the Southern Pacific Railroad. Their fortune allowed Fassett to venture into Korean gold mining. When Japan annexed Korea and required technical expertise, Hoover lept at the chance, but was unsuccessful. He then journeyed to Siberia where his team found high quality ore. The Bolshevik Revolution spoiled their prospects. Thirty-four years later, at the height of the Cold War, Hoover reminisced, “Had it not been for the First World War, I should have had the largest engineering fees ever known to man.”

Beer baron Adolph Coors owned Korean gold mines. Until the Second World War, Korean gold “was mostly a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Republican right-wing.” After the war, General MacArthur and his right-hand man, Brigadier General Courtney Whitney invested in the largest Philippine gold mine at Benguet. Whitney also drafted the Japanese Constitution.[16]

In a March 3, 1950, speech at the Waldorf-Astoria, New York City’s most luxurious hotel, General Robert L. Eichelberger, former commander of the Eighth Army in Japan, delivered a speech on the need to rearm Japan and the strategic importance to the U.S. military of Korean tungsten. Later, Eichelberger’s brother won a huge contract for extracting Korean tungsten, and the U.S. became the recipient of Korea’s entire annual output.[17]

Staggers’ game plan and the financial schemes of these U.S. dynasties were reflected in a 1947 directive relayed by Secretary of State George C. Marshall to Dean Acheson who in 1949 would succeed Marshall as Truman’s Secretary of State: “Please have plans drafted of policy to organize a definite government of South Korea and connect up [sic] its economy with that of Japan.” [my bold] Acheson, the son of the Episcopal bishop of Connecticut, graduated from Yale. After Harvard Law School, he became a lawyer for Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. He regarded Japan as the “obstreperous offspring” of Western civilization.[18]

To enforce ideological conformity and whitewash Japanese atrocities, General Charles A. Willoughby ordered in 1947 that Andrew Grajdanzev, the 1944 author of what Cumings termed the “best English-language account of Japanese rule in Korea,” be followed and have his mail opened to find anything that would smear his credibility. Willoughby, General MacArthur’s Intelligence Chief, had interests in Korean and Mexican mines. He claimed to have changed his name from Adolf Karl Tscheppe-Wiedenbach, and that he was the son of a German baron and a Baltimore, Maryland mother. Upon his arrival in the United States, Willoughby joined the army. He rose rapidly through the ranks. Mussolini’s government honored Willoughby with Italy’s highest decorations. He praised General Franco as “the second greatest general in the world.” According to David Halberstam, Willoughby bore the lion’s share of responsibility for discounting the potential for Chinese intervention in the Korean War.[19]

In 1950, just before that war broke out, Willoughby supplied Joseph McCarthy with false information that the Wisconsin Senator used to blame State Department officials for “losing” China. McCarthy boasted, “I’ve got a sock full of s_ _t and I know how to use it.” [20]

Meanwhile, Truman’s Attorney General, J. Howard McGrath, stirred the pot of war by calling communists “rodents” and accusing the Soviet Union of “international sadism.” [21]

The war became the pretext to save Taiwan for Chiang Kai-Chek and roll back communism on the Chinese mainland, Korea, and elsewhere, while at the same time lining the pockets of war profiteers and precious mineral speculators. The New York Times along with major Republican Party publishers fed the public the kind of propaganda that reinforced Intelligence Chief Willoughby’s claims that the communist triumph in Asia was the work of a pan-Slavic “Jehad,” rather than an indigenous mass movement.[22]

McCarthy’s campaign diverted attention from the harsh truth that many of his upper-class boosters like William Randolph Hearst and Prescott Bush had been active Nazi supporters before and during the early stages of World War II; and many of McCarthy’s targets, for instance, Harry Dexter White, had been unwiling to let these facts go unnoticed. Upon retirement from the army, Willoughby became an advisor to Spain’s Franco, worked with oilman H.L. Hunt on the International Committee for the Defence of Christian Culture, and was inducted into the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame.

In May 1948, Rhee held elections. On election eve, he arrested thirty of his leading opponents. Even so, Rhee’s party garnered only 48 seats in the Assembly, with 120 going to the left-wing opposition. The new Assembly called for unification of the country, even if on the North’s terms.

Rhee’s Japanese-trained army commanders of his South Korean Army (ROKA) were furious, and ordered their men to go on a savage rampage. Under the watchful eye of the U.S. Army, the ROKA massacred more than 30,000 civilians on the southern Korean island of Cheju between October 1948 and February 1949. Many were forced to kneel with their hands tied behind their backs before being doused with gasoline and set afire while alive. General Hodge had characterized Cheju Island before the massacre as “a truly communal area…peacefully controlled by the People’s Committee without much Comintern [i.e. Soviet] influence.” [23]

The number killed in this one of many atrocities inflicted upon the Korean people was more than ten times the number of lives lost in the 2001 World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks. Washington used 9/11 as the pretext to initiate an invasion of Afghanistan, and afterwards Iraq. Is it any wonder then that war broke out between northern and southern Korea? But at the time, Washington censors succeeded in preventing the truth from emerging. [24]

During 1949, the New York Herald Tribune reported, “An unadmitted shooting war between the Governments of the U.S. and Russia [sic] is in effect today along the 38th parallel …Only American money, weapons, and technical assistance enable [South Korea] to exist for more than a few hours … [South Korea is] a tight little dictatorship run as a police state.”[25]

NARA

The first battle, May 4, 1949—the biggest–initiated a series of clashes that culminated in the publicly declared start of the Korean War on June 25, 1950. This May 4th combat occurred when Rhee’s forces crossed the 38th parallel, only to have two of his infantry companies defect to the communist side. Numerous August skirmishes led the U.S. Korean Military Advisory Group Commander, General W.L. Roberts, to conclude, “Each was in our opinion brought on by the presence of a small south Korean salient north of the parallel …the South Koreans wish to invade the North. … almost every incident has been provoked by the South Korean security forces.” By June 25, 1950, hundreds of troops had been killed as thousands of soldiers fought countless small engagements. Convincing evidence has yet to be shown that the North was preparing to invade the South. The only U.S. newspaper Cumings found that published the truth about how the war began was the U.S. Communist Party’s Daily Worker.[26]

CIA reported to itself, “the regime and its policies command little positive support.” Cumings agreed, “many moderates chose it [North Korea] over the American-supported South. …it is unquestionable that Rhee and his regime could never have survived without American backing.”[27]

Cumings’s prodigious research led him to conclude that “…little evidence of Soviet or North Korean support for the southern guerrillas” existed before the Korean War broke out. “The principal source of external involvement in the guerrilla war was, in fact, American,” led by the self-described “father of the Korean Army,” Captain James Hausman.” Soviet presence was scant. [28]

Indeed, Rhee’s plan encouraged by U.S. Congressmen consisted of goading the North into all-out war that secretly deployed Japanese troops fresh from massacring Chinese civilians [my bold].[29] On September 30, 1945, Rhee communicated with registered lobbyist Robert Oliver, Professor of Public Speaking at Penn State University, who wrote many of Rhee’s speeches:

I feel strongly that now is the most psychological moment when we should take an aggressive measure and join with our loyal communist army [sic] in the North to clear up the rest of them in Pyongyang [North Korean capital]. We will drive some of Kim Il Sung’s men to the mountain region and there we will gradually starve them out. Then our line of defense must be strengthened along the Tumen and Yalu River [i.e. the Sino-Korean border]. [30]

Cumings points to “a highly secret plan” to have a Korean War, in effect making it “Japan’s Marshall Plan” to rebuild that country. A Captain Ross Jung acted as G-2 liaison between Chiang’s Nationalist Chinese government and State Department Intelligence when the last U.S. troops formally withdrew in June 1949. For the first time since World War II’s end, there were no U.S. troops in South Korea, just a slew of advisors. They left behind military equipment of greater value than the entire annual South Korean government budget.[31]

On October 10, 1949, Oliver wrote Rhee:

On the question of attacking northward, I can see the reasons for it, I think, and sympathize with the feeling that offense is the best and sometimes the only defense. However, it is very evident to us here that any such attack now, or even to talk of such an attack, is to lose American official and public support …The strong feeling …is that we should continue …to avoid any semblance of aggression, and make sure the blame for what happens is upon Russia.

On October 12th, Pyung Ok Chough, Ambassador Plenipotentiary, Personal Representative of the President of the Republic of Korea and Permanent Observor to the United Nations, wrote his employer:

It is with great care and interest that I read your letter to Dr. Oliver with regard to … the disposal of the puppet regime in the North. The proposals you expounded therein are … the only logical and ultimate method for bringing about our desired unification. However, the time is not opportune as yet …I am sure he [Oliver] cannot publicize such a proposal as our fixed government policy. Nor do I think that it would be wise for him to make public such matters of secret import. I have discussed that this matter should be regarded as the basic plan of our Government that should be carried out when we are ready and the time is opportune.

Rhee and MacArthur conspired to roll back communism and restore the Japanese economy. Indeed, Korea’s richest man and Rhee’s largest financial backer, Pak Hung Sik, made a fortune during World War II supplying airplane parts for Japanese kamikaze planes. Private dispatches revealed an active interest in Japan’s genocidal bacteriological warfare program in Manchuria. MacArthur shielded its head, General Shiro Ishii, so he and thousands of his acolytes could aid the U.S. military in similar ventures. In Seoul, Washington built the largest embassy in the world and fielded the biggest “aid” mission, as well as deployed its largest number of “advisors” anywhere in the world. [32]

By late 1949, seasoned Korean troops with Chinese, not Soviet, battlefield experience, returned to Korea after the communist military triumph on the Chinese mainland. Twenty-five per cent of the Chinese communist forces fighting Chiang-kai-Chek in Manchuria (150,000 men) were Korean. They were better fighters than ROKA. The Chinese Communist Party leadership appreciated their aid in driving Chiang’s forces into the sea.[33]

Korea became the first overt military test case for CIA. While President Truman, the heads of the Joint Chiefs, and the chair of the Foreign Relations Committee all stated that the islands of Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines that formed an arc around a newly communist China were sufficient to protect U.S. global interests as defined by big business; only CIA regarded Korea as strategically important. Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chair, Tom Connally, warned on May 2, 1950, that he feared South Korea would have to be abandoned. Connally stated that he did not think South Korea was “very greatly important. It has been testified before us that Japan, Okinawa, and the Philippines make the chain of defense which is absolutely necessary.” Prior to the release of NSC 68, Connally’s stance was identical to that of Truman’s, and to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. They concluded on September 22, 1947, that “from the military point of view [Korea was] of little strategic interest to the U.S. [and no strategic purpose would be served by] maintaining the present troops and bases.”[34] The State Department represented by George Kennan agreed that withdrawal from Korea presented the most sensible course of action.

Once they were informed of NSC 68, they quickly tailored their views to conform to CIA’s. This clandestine position paper charted a new, more vigorous military course for the U.S. in the world, one that made securing Korea a vital objective even if it meant murdering millions of people.

Acheson did his level best to cause an all-out civil war in the Korean nation to achieve Washington’s goal of establishing a military bastion in the Chinese and Russian sphere of influence. A secondary objective was to divide the USSR from a now inevitable Communist China.[35]

The ultimate failure to accomplish this second goal more than any other single factor doomed the Anglo-American Empire. Consistent with Toynbee’s empire hypothesis, the U.S. economy and those of its NATO allies were bled through “endless wars.” Acheson displayed sneering contempt for Congress: “I used to tell them lots, but never the whole truth … [Congress] can be troublesome and do minor damage like boys in an apple orchard.” [36]

Right-wing political forces were gung-ho to roll back communism wherever it was. Their military savior was Douglas MacArthur. James Burnham, a former Trotskyite from a rich Chicago family, was privy to the drafting of NSC 68. He observed, “A plan of military rearmament and development is at present going forward.” With Time magazine founder Henry Luce’s (Bones 1920) solid backing, Burnham authored The Coming Defeat of Communism (1950) and worked with CIA’s William F. Buckley to found the preeminent conservative journal, National Review.[37]

Burnham depicted the United States as “a child, a border area of Western civilization … crude, awkward, semi-barbarian, nevertheless enters this irreconcilable conflict as the representative of Western culture.” Court historian, Arthur S. Schlesinger, Jr., proclaimed Burnham’s stance as better than the “confusion and messy arguments of the appeasers.”

McCloy went a step further. He boasted in a February 27, 1950 Life magazine article, “If there were an oxygen bomb that would be bigger than the H-bomb, I would build it.”[38] He was aware that the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the People’s Republic of China had announced the signing on February 15th of the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance. Stalin promised Mao a most favorable trade agreement. and military protection against any future Japanese attack.

British Consul General, Vyvyan Holt, recounted the extent of Washington’s involvement in Korean daily life with a message to his Foreign Office on May Day, 1950:

Radiating from the huge ten-storied Banto Hotel, “American influence” penetrates into every branch of administration and is fortified by an immense outpouring of money. Americans kept the government, the army, the economy, the railroads, the airports, the mines, and the factories going, supplying money, electricity, expertise, and psychological succor. American gasoline fueled every motor vehicle in the country. American cultural influence was exceedingly strong, ranging from scholarships to study in the United States, to several strong missionary denominations, to a score of traveling cinemas and theaters that played mostly American films, to the Voice of America, to big-league baseball:

“America is the dream-land’ to thousands if not millions of Koreans. [39]

Less than a month before the war was splashed over the front page, the New York Times characterized Korea as “the dagger pointed at Japan’s heart. An abrupt American withdrawal [from Korea] would mean the collapse of the free Korean state and the passage of the dagger once more into Russian hands…. What it comes down to is that if Japan is to be defended all of Japan has to be a base, militarily and economically.” [40]

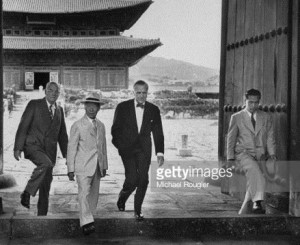

Between 1945 and June 1950, MacArthur made just two trips outside of Japan, and both were to Korea. He stated that an attack on South Korea by its northern compatriots would be equivalent to an attack on California. [41] By June 1950, it had become clear that Rhee could not hold onto South Korea, or Chiang Kai Chek to Taiwan, without American military intervention, even though the U.S. was providing massive military and financial aid to the South Korean army (ROKA).[42]

Chinese communists had already liberated other large islands off their coast including mineral-rich Hainan Island on April 23rd, and were on the verge of completing the process by landing on Taiwan.

Voters had soundly rebuffed Rhee supporters in the May national elections, even though he had jailed many candidates like he did in 1948. The charge of being a communist helped one get elected.[43] Hence, a war became the only means for Rhee and the Americans to retain power.

Time was a critical factor because the Democratic Front for the Unification of the Fatherland (DVVF) was buoyed by the recent election results and called for a June 9th meeting with North Korea that would organize joint North/South elections in August to choose a new united National Assembly. Rhee’s response was to threaten execution for any one who attended.[44]

Meanwhile, CIA head Donovan was organizing a coalition of nations on the Chinese border to sponsor state terrorism within China, reminiscent of what Washington did in the newly formed Soviet Union. Under UN cover, Donovan sanctioned use of Japanese airmen in Taiwan to bomb China. Both the U.S. and Great Britain intelligence services predicted that “the last battle” for China would take place in June. The “fate of Taiwan” appeared sealed with an attack predicted “between June 15 and end of July.” [45]

Washington policymakers regarded a probable communist triumph in Taiwan as a threat to restoration of Japanese capitalism and its oil interests in Indonesia that would then place “`the oil of the Middle East in jeopardy.’” [46] Taiwan would provide the U.S. with a base from which to launch a rollback of communism on the Chinese mainland.

Acheson had desired to separate Taiwan from China for more than a year. To implement a plan, he met with Rusk, Nitze and Dulles on May 31 and June 9. On the propaganda front, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. gave a scholarly talk in which he compared the Soviets to the Nazis by seeking to create “a master race.” [47] Early in June, the State Department drew up a resolution to submit to the UN Security Council condemning North Korea; it conformed to the aims set forth in the Oliver/Rhee correspondence just cited.

On June 18, Dulles visited Seoul to confer with Rhee. The next day, the Pentagon distributed war plan SL-17, “which assumed a KPA invasion, a quick retreat to and defense of a perimeter at Pusan, and then an amphibious landing at Inchon.” Dulles, whom Rhee publicly extolled as “the Father of the Republic of Korea,” left on the 21st for Tokyo where he met with MacArthur on the evening of the 25th. The general had already dispatched military aid, and told Carl McCardle of the Philadelphia Bulletin, “Russians are Oriental, and we should deal with them as such …they are mongrels.” Five days earlier, General Ridgway had redirected ordnance from Indochina to Korea.[48]

An Australian embassy official reported in late June that patrols were going in from the South to the North, endeavoring to attract the North back in pursuit … it was clear that there was some degree of American involvement as well as the South Koreans wishing to promote conflict with American support.

Former Australian Prime Minister, E. Gough Whitlam, corroborated:

Less than a week before war erupted … the Australian Government had received reports of intended South Korean aggressions from its representative in South Korea. The evidence was sufficiently strong for the Australian Prime Minister to authorize a cable to Washington urging that no encouragement be given to the South Korean government. That cable cannot be found among official papers in Australia. [49]

The Secretary of the Australian Foreign Office, John Wear Burton resigned in protest and was replaced on June 19—his Foreign Service effectively terminated. Burton stated, “All these telegrams have now vanished from the F[oreign] O[ffice].” Many years later in an interview with Cumings, he related, “there has been a high level attempt to cover all this up.” [50]

On the 25th came the well-orchestrated pretext for massive U.S. involvement when fighting was reported north of the 38th parallel at Haeju on the Ongjin Peninsula. Two-thirds of the South Korean Army was stationed at or near the border between the two Koreas. Cumings observed that the Ongjin Peninsula is situated in a cul-de-sac, “hardly the place to start an invasion if you are heading southward …It’s a good place to jump off if your heading northward, since it commands transportation leading right to Pyongyang, and in June 1950 was remote from the Seoul-based American attempts to rein in southern army commanders.” [51]

Officers schooled in the Japanese Kwangtung Army commanded the 17th division involved in the Ongjin conflict. They were adept at manufacturing successful provocations like the 1931 Mukden Incident that provided the excuse for Japan’s conquest of mineral-rich Manchuria the following year. For the Korean War, General Willoughby’s intelligence reports for that last weekend in June are mysteriously missing.

We do know for sure that the South Korean army retreated south accompanied by their U.S. military “advisors” killing tens of thousands of unarmed civilians along the way, including many women, children and unconvicted prisoners. After the war ended in 1953, “Many of these human butchers and their children…[became] rich and powerful,” [52] following the example set by Japanese war criminals.

One of these joint U.S. Army/ROKA bloody episodes involved a US Army Lieutenant Colonel advising his South Korean counterpart that “it would be permitted” to machine-gun 3,500 political prisoners. In the course of a few weeks at the war’s onset, over 100 thousand leftists and their sympathizers were killed without charge or trial and dumped in mass graves in at least 168 sites uncovered to date—or just dropped into the ocean.[53]

Washington hid classified files from the public about the number of children shot as U.S. officers looked on. They were allegedly the “families of suspected leftists,” according to the South Korean government’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission established on December 1, 2005. U.S. Army photographers took photos of the assembly-line executions outside Daejeon city where as many as 7,000 people were murdered. At the time, only communist papers published the truth about the carnage.

General MacArthur, the Pentagon and the State Department promoted the bloodletting and kept the facts from an unwitting American public. The truth seeped out over a long period of time, accelerated by hardy investigative reporting and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. [54]

One particularly gruesome three-day slaughter of hundreds of women, children and old men became the subject of a Pulitzer Prize winning book based on interviews with over 500 U.S. veterans and a trove of data, including “yards of files of declassified military documents.” Still, no formal apology was forthcoming from Washington, although President Clinton issued a statement of “deep regret.” [55]

Contrast the Korean and U.S. soldiers’ genocidal rampage to North Korean treatment of Southerners when they briefly took control of South Korea from Rhee and the Americans:

Every soldier and official behaved like a political officer, using extensive face-to-face communications. Workers were quickly brought into mass organizations, and students held endless rallies to support the war and volunteer. Korea’s long-abused women were a major target of the regime. The Women’s League established organizations at every level, its workers distributing pamphlets door-to-door. Every PC had to have at least one woman; “women held jobs of honor, worked at employment usually denied them, [and] sometimes went around calling each other tongmu [comrade].” If a soldier met a woman in the street, he would lecture her on woman’s equality.[56]

In that liberating summer of 1950, many women were elected to the people’s committees that governed the countryside. More land distribution took place, especially for poor peasants, than at any time in the history of southern Korea where Rhee’s regime routinely compelled the peasantry to supply rice to Japan. [57]

The three major themes stressed by communist educators were “reunification, land reform, and the restoration of the people’s committees.”[58] U.S. military researchers judged the communist economic and social programs to be a stunning example of grassroots democracy i.e. “a nearly autonomous administration, answerable to the community through elections” that provided services “on a scale never attempted before.”[59]Washington ignored this progressive pedagogy because it ran counter to NSC 68’s new world order blueprint that commanded the U.S. to meet “each fresh challenge promptly and unequivocally.”

Truman did not consult a single European or Asian ally, nor Congress—but only his foreign policy advisors—when he sent American troops into the Korean conflict. He had learned from his Missouri handlers, the Kansas City Pendergast gang; just follow orders from the boss, even when the boss is involved on city streets in “machine gun terrorism” as the Associated Press characterized Kansas City government. The main difference was that “Wild Bill” Donovan had replaced Tom Pendergast.

Truman did not consult a single European or Asian ally, nor Congress—but only his foreign policy advisors—when he sent American troops into the Korean conflict. He had learned from his Missouri handlers, the Kansas City Pendergast gang; just follow orders from the boss, even when the boss is involved on city streets in “machine gun terrorism” as the Associated Press characterized Kansas City government. The main difference was that “Wild Bill” Donovan had replaced Tom Pendergast.

Truman followed the precedent set by FDR’s secret summer 1941 war in the Atlantic. One could wage war without declaring it, a violation of the Constitution to which all the lawyers in Congress acquiesced, except one, the “people’s congressman”—Vito Marcantonio. He was soon out of office when the Democrats, Republicans and Liberals ganged up to support one James Donovan who defeated Marcantonio for re-election the year the Korean War became front-page news. Meanwhile, charter Pendergast gang member, William Marshall Boyle, Jr., chaired the Democratic National Committee until he resigned in 1951 due to an influence peddling scandal. Truman worked fast. One day was all it took for him to respond to NSC 68 and Acheson’s stage directions. As Stephen Ambrose observed, “For a man who had been surprised, he recovered with amazing speed.”[60]

On June 26th, Truman expanded the Truman Doctrine to incorporate the Pacific Ocean. He ordered the U.S. navy and air force to provide military support to South Korea, and interposed the U.S. Seventh Fleet between the Chinese mainland and Taiwan to thwart an inevitable communist victory on this large island. The head of the Democratic Party pledged formal aid to the French fighting Ho Chi Minh’s communist forces in Indochina, the CIA-subsidized Philippine government fighting a communist uprising, and right-wing terrorists in Indonesia.

The United Nations followed Truman’s lead and passed a resolution to support military action in Korea because it routinely accepted the U.S. and South Korean positions as gospel. The UN “became a partisan in the civil conflict” with its UN Temporary Commission on Korea following Rhee around like a dog.[61]

The UN resolution marked the first time in history that an international organization had ordered an army to war. It happened only because the Soviets were staging a boycott to protest UN recognition of Chiang’s Taiwanese government as the legitimate UN representative for China. Meanwhile the British and French had already recognized the Chinese Communist government, something that Washington did not do until 1979, thanks to Chiang’s stolen Chinese gold going into Congressional pockets.

Money flowed freely to buy favorable press coverage that portrayed Rhee as standing for “freedom and democracy” against “godless communism.” Washington used Christianity to sanctify the Korean War. The chaplain to the U.S. Senate, the Rev. Frederick Brown Harris, extolled Rhee as “a God-intoxicated man, praying with Christian love even for his enemies … [God] is for him the reality behind every sham, the dynamic behind every thought of his brain, every beat of his heart, every breath of his body.” [62]

Rhee paid American journalists to spin praise while they worked for U.S. publications. Ray Richards, a Tokyo-based Hearst correspondent, was paid $850 per month—double a full professor’s salary in those days—to write puff piecesvthat appeared routinely in the Hearstpress acrossr the country without any one of the millions of readers apprised that they were reading propaganda.

Just as important to the furtherance of U.S. global aims were the benefits this war brought to the Japanese economy. To that end, Washington prevented any serious prosecution of Japanese war crimes, and secretly tapped the genocidal talents of the Japanese military in its own invasion of South Korea that included crushing the Korean labor movement “with most of its leaders dead or in jail.” [63]

While Republicans ranted about “the loss of China” as if China belonged to them, and the North Koreans sweeping down the Korean peninsula, on June 30th Truman ordered that U.S. troops stationed in Japan proceed to Korea. Truman stressed that the United States aimed only “to restore peace …and the border.” “Containment”, not “rollback”, was Washington’s official position; however, NSC 81, written mainly by Rusk, authorized “rollback” in North Korea only if Russians or Chinese did not become involved. [64]

So many US troops poured into Korea so fast that South Korea was in a position to annihilate the North Korean army. On September 12th, a cocky Secretary of State Acheson proposed to create ten German divisions. The British and French governments objected because it came too soon after the Nazi defeat to be palatable to Europeans, especially to the very many civilians liberated by Stalin’s Red Army.

Fifteen days later, in what Truman described merely as “a police action,” the Joint Chiefs ordered MacArthur to destroy the enemy army north of the 38th parallel. On October 7th, American troops crossed the parallel. That same day by a vote of 47 to 5 the U.N. approved the American resolution endorsing military intervention.

Newspapermen relying upon heavily censored communiques issued by MacArthur’s Tokyo headquarters misled many millions of Americans. Ignored or reviled were those rare journalists like Scott Nearing, George Seldes and I.F. Stone who took their jobs seriously enough to ferret out the deceptions. The Monthly Review correctly assessed the outbreak of hostilities as an expression of a civil war that would result in “a disastrous defeat” for the U.S. [65]

The Chinese publicly announced that they would not “sit back with folded hands and let the Americans come to the border.” On October 10th, U.S. aircraft strafed a Soviet airfield a few miles from Vladivostok. Moscow vigorously protested to Washington. The next day, the Chinese publicly warned that they would enter the conflict if U.S. forces ventured further north.

Truman, MacArthur, and every one else involved in the decision-making process in Washington ignored the Chinese warning. They were intent on using Korea as the pretext to roll back communism in the world’s most populous nation. Chinese support for the North Koreans would be the pretext.

On October 25th, MacArthur reached the Yalu River that separates North Korea from China. The same day the Chinese struck back, driving MacArthur’s men south. The Chinese then halted their advance.They would not allow the Pentagon control of the border with China, but wanted to talk about Korea and Taiwan. They journeyed to the UN for that purpose. Truman, Acheson and MacArthur were not interested in negotiation. If peace came so soon, the objective of NSC 68 could not be fulfilled. MacArthur decided to time his offensive for November 24th, the very day that the Chinese were to speak at the UN.

Europe was alarmed. The French government protested that MacArthur had “launched his offensive at this time to wreck the negotiations.” The Chinese delegation immediately returned home. From the safety of the White House Truman was miffed by the failure of the offensive. MacArthur had advanced on two flanks leaving his middle wide open. The Chinese did the obvious. They filled the gaps, and U.S. soldiers fled for their lives. In two weeks, the Chinese had completely reversed the military situation. Most of South Korea fell, including Seoul. MacArthur’s units retreated to three bridgeheads. It would take two more years and more than 20,000 additional American lives sacrificed to settle for what Washington had in Korea before attempting to conquer the North and threaten China. Still, Taiwan was in U.S. hands, North Korea became a wasteland due to genocidal bombing from the air, and the rebuilding of South Korea would assist the reconstruction of Japan.

After the Chinese entered the war and helped North Korea to liberate their homeland, eye wittnesses detailed the atrocities committed by the South Korean forces. Cumings wrote:

United Press International estimated that eight hundred people were executed from December 11 to 16 and buried in mass graves; these included `many women, some children,’ executed because they were family members of Reds. American and British soldiers witnessed `truckloads [of] old men [,] women [,] youths[,] several children lined before graves and shot down.’ A British soldier on December 20 saw about forty `emaciated and very subdued Koreans’ being shot by ROK military police, their hands tied behind their backs and rifle butts cracked on their heads if they protested. The incident was a blow to his morale, he said, because three fusiliers had just returned from North Korean captivity and had reported good treatment. Elsewhere, British troops intervened to stop the killings, and in one case opened a mass grave for one hundred people, finding bodies of men and women, but in this case no children. There were many similar reports at the time, from soldiers and reporters. The British representative in Northern Korea said most of the executions occurred when KNP [Korean National Police] officials sought to move some three thousand political prisoners to the South. `As threat to Seoul developed, and owing to the destruction of the death-house, the authorities resorted to these hurried mass executions by shooting in order to avoid the transfer of condemned prisoners South, or leaving them behind to be liberated by the Communists. …’[66]

[U.S Ambassador to Korea] Muccio … backed him [Rhee] up, defending the ROK against the atrocity charges. …CIA sources commented with bloodcurdling aplomb that ROK officials had pointed out to UNCURK [UN Commission on the Unification and Rehabilitation of Korea] that `the executions all followed legal trials,’ and that MacArthur’s UN Command `has regarded the trial and punishment of collaborators and other political offenders as an internal matter for the ROK.’ …Many of the witnessed murders in fact had no legal procedure whatsoever, and were carried out not just by police but by rightist youth squads. A Japanese source, cited by a conservative scholar, estimated that the Rhee regime executed or kidnapped some 150,000 people in the political violence of the North’s `liberation.’ [67]

In December 1950 with South Korea devastated, Colonel Goodfellow focused in true Lockean fashion on private property. He ordered his Secretary “to find a man who wants to buy a lot of scrap of all kinds … Korea is so full of it.” [68]

At a November 30, 1950, news conference, Truman threatened to use atomic bombs on Korea. British Prime Minister Clement Atlee quickly flew to Washington to dissuade Truman from using this horrific weapon for the third time in five years against Asians. War against China would mean war against the Soviet Union.

Congressman Al Gore, Sr. (2000 Democratic Presidential candidate Al Gore’s father) suggested dropping enough nuclear weapons to create a radiation belt across the Korean peninsula. Of course, much of Asia, if not the entire planet, would have been poisoned.

The Soviets knew of the behind-the-scenes decision-making because CIA/MI6 joint operations had been deeply penetrated by mostly Cambridge University educated Soviet intelligence moles in one of history’s most remarkable spying ventures. Guy Burgess headed up London’s Far Eastern Office and moved to Washington in August 1950 where he assumed a similar role. Donald Duart Maclean, son of Britain’s Liberal Party leader in the 1920s was stationed in London during most of World War II. From 1944 to 1948, he transferred to Washington to serve as British Embassy Secretary. He mined Roosevelt and Churchill’s secret correspondence, and upon Roosevelt’s death, between Truman and Churchill and his successor Clement Atlee. George Blake was MI6 Intelligence Chief in Seoul, Korea, before and during the opening stages of the war when he was captured and taken to North Korea. Burgess, Maclean and Blake apprised the Kremlin of the detailed planning that went into the U.S. invasion of North Korea, as well as General MacArthur’s spurious intelligence reports designed to influence Washington policymakers into supporting his military actions. MacArthur’s forged documents purported to demonstrate on racist grounds that Moscow directed every move of the Chinese communists. [69]

Then there was art historian and Soviet spy Sir Anthony Blunt. He personally conducted Queen Elizabeth, to whom he was distantly related, on tours of her Windsor Castle art collection in his official capacity as Surveyor of the King’s Pictures (1945-1972). Blunt served as Director (1947-1974) of the Courtauld Institute of Art, an international center that houses Great Britain’s foremost art history program.

Finally, there was Kim Philby, arguably the most successful spy in history, who directed British Counter-Intelligence against the USSR and frequently briefed Churchill whose confidential intelligence Philby secretly relayed to Stalin. Philby was dispatched to Washington where he served as London’s chief liaison to CIA, the FBI, and the NSA. According to a top CIA official, Philby had complete access to anything he wanted. “The sky was the limit. He would have known as much as he wanted to find out.” U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union (1946-1948) and CIA Director (1950-1953) General Walter Bedell Smith briefed him “on policy.” CIA’s Counter-Intelligence chief James Angleton lunched with Philby once a week. Harvard Law School graduate Angleton realized there was a mole in CIA’s midst, but wrongly fingered establishment figures like Averell Harriman. Angleton never once suspected his lunch companion.[70]

The weakest member of this upper-class spy team turned out to be the only American—Michael Whitney Straight. He ran the New Republic magazine because his investment banker father, Willard Straight, founded the magazine with wife Dorothy of the prominent Whitney dynasty; and Herbert Croly. In the 1930s, Michael went to Trinity College, Cambridge University, where he was recruited by Blunt. When he returned to the United States in 1937, he got a job writing speeches for President Roosevelt. In 1940, he joined the Eastern Division of the U.S. State Department. In 1963, he informed on Blunt to City University of New York U.S. historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. who possessed deep CIA ties.

While these impeccably educated upper-class spies were motivated by social injustice, Washington used its financial muscle to bribe clients and fix elections in European nations like Italy and Greece; along with a torrent of fiery bombs to unsuccessfully subdue Asians. A major secret source of funding came from the tons of gold bars and rooms of priceless art that Japan had looted from a dozen Asian nations that it stored in mountain caves and tunnels in Luzon, the Philippines. MacArthur confiscated most of it and Truman used these secret riches to further Washington’s foreign policy agenda.[71]

By February 1951, Truman had received emergency powers from Congress to activate war mobilization. He reintroduced the draft, increased the Army by 50% to 3.5 million men, sent two divisions for a total of six to Europe, doubled the number of air groups to ninety-five, obtained new bases in Morocco, Libya and Saudi Arabia, stepped up aid to the French in Vietnam, came out for adding Greece and Turkey to NATO, and initiated discussions with Franco that led the U.S. to aid fascist Spain in return for military bases there.

The next month, the Truman administration successfully tested a thermonuclear bomb and rearmed Germany. It pushed through a peace treaty with Japan that excluded the Russians and gave the United States seven military bases, and allowed for Japanese rearmament and unlimited industrialization. It unilaterally dismissed out-of-hand British, Australian and Chinese demands for reparations.

Washington sacrificed long-term public interest for short-term military gains. It carried out the foreign policy objectives set by CIA that included doubling the size of the armed forces, and boosting corporate profits by ladling out spendthrift and corrupt military contracts like the one with the Lockheed corporation. Nevertheless, two crucial strategic objectives had been achieved. The Korean War placed the United States on a cold war footing. U.S. military expenditures in Korea primed Japan’s post World War II industrial recovery and greatly expanded its Asian markets.[72]

On April 11, 1951, President Truman relieved General MacArthur of his command. As Cumings discovered, MacArthur and his intelligence crew had kept CIA from knowing the details of the war effort with which he had been charged. “But with the debacle of the Chinese entry into the war, the power struggle ended with a clear CIA victory.” [73]

became infamous in Vietnam, but much more was dumped on North Korea. (Photo: AP)

During 1952, President Truman waged a “a holocaust on the North.” The U.S. Air Force burned alive soldiers and civilians in sorties that daily dropped 70,000 gallons of napalm. They successfully employed helicopter gunships for the first time, bringing to horrible life Da Vinci’s futuristic sketches. The U.S. Air Force was used “to pulverize North Korea.” [74]

American bombing was far more extensive than revealed at the time to the American public, or subsequently admitted to by Washington. MacArthur called for destroying from the air every “installation, factory, city and village,” in order to transform North Korea into a wasteland.[75]

Biological weapons were secretly used in violation of the Geneva Protocol of 1925. The bacteriological contamination was due to MacArthur sending to Korea the unrepentant head of Japanese BW research during World War II to participate in U.S. military experiments on the North Korean population.[76] By the end of 1950, US pilots were dropping fleas infected with the plague, and turkey feathers coated with toxins. In 1952, an international scientific inquiry led by Dr. Joseph Needham of Cambridge University, concluded that the United States was guilty of conducting bacteriological and chemical warfare against both China and Korea. The air force released swarms of locusts on bean stalks and tree leaves, and dropped cardboard boxes containing decaying pork, frogs and rodents, contaminated by various lethal toxins generated at Fort Detrick, Maryland and Plum Island, off Long Island, New York. The U.S. Army took advantage of the fact that Seventh Day Adventists are forbidden to bring suit in civil court, and used them as human guinea pigs in a germ warfare program known as “White Coat.” [77]

Dwight D. Eisenhower became President later that year. In May 1953, he ordered the U.S. Air Force to destroy the Toksan Dam and four other dams. They supplied the water to irrigate 75% of North Korea’s rice fields. The largest, the Toksan dam complex, was destroyed the same day that the Rosenbergs were executed; allowing the dam bombings to receive far less press coverage than the executions.

At the 1945-1949 Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal, of 185 Nazis indicted, 24 were sentenced to death, including the German High Commissioner in Holland who ordered the opening of Dutch dikes to slow down the Allies’ advance. Five hundred thousand acres were flooded and mass starvation resulted.

In Korea, the U.S. Air Force rationalized its dam bombings in racist terms: “To the Communists the smashing of the dams meant primarily the destruction of their chief sustenance—rice. The Westerner can little conceive the awesome meaning that the loss of the staple food commodity was for an Asian—starvation and death.” Whereas the North Korean civilian death toll for the Korean War represented 20% of the total population of North Korea, total Japanese civilian and military deaths amounted to 3% of their population for the entire Second World War [my bold]. [78]

Hungarian correspondent Tibor Meray was in North Korea when the Pentagon rained down death and destruction. He reported, “Everything which moved in North Korea was a military target, peasants in the fields often were machine gunned by pilots who I, this was my impression, amused themselves to shoot the targets which moved …a complete devastation between the Yalu River and the capital …no more cities in North Korea … We traveled in moonlight, so my impression was that I am traveling on the moon, because there was only devastation … [E]very city was a collection of chimneys. I don’t know why houses collapsed and chimneys did not, but I went through a city of 200,000 inhabitants and I saw thousands of chimneys and that—that was all.” [79]

The August 14, 1945 order from “Chairman of the American Establishment” McCloy to divide Korea had set in motion a chain of events that led directly to the deaths of four and a half million Koreans and fifty-five thousand Americans, and the rebuilding of a capitalist Japan. All parties, except the South Korean government, signed an armistice agreement on July 27, 1953. There is no formal peace treaty to this day.

Rhee left the country in 1957 as protestors tried to storm the Blue House, South Korea’s equivalent to the US White House. Rhee had rigged yet another election in his favor and CIA airlifted him out just in time. His odyssey as Washington’s man in Korea was over.

[1] Kolko, The Politics of War, 603.

[2] Sterling and Peggy Seagrave, Gold Warriors. America’s Secret Recovery of Yamashita’s Gold (New York & London: Verso, 2003), 21.

[3] Record Group 335, Secretary of the Army file box 56, Osgood to William Draper, Jr. November 29, 1947. Cited in The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 188. Draper served as Chief of Staff of the 77th Division of the U.S. Army and Secretary of the Army while Vice President of Dillon, Read & Co. This investment bank underwrote millions of dollars of German industrial bonds before World War II. Consistent with his active role in the eugenics movement, Draper strongly supported restoring former Nazis to power. He was appointed to the rank of Major General and served as first U.S. Ambassador to NATO (1953). Afterwards, he became Chairman of the Mexican Light and Power Co. (1954-1959), and then U.S. delegate to the UN Population Commission (1969-1972). Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 458.

[4] Bruce Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun. A Modern History (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1997), 228. Record Group 242. Cited in op cit, 301.

Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 328.

[5] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 62-63.

[6] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 234.

[7] Goodfellow Papers, Box 1 (Hodge to Goodfellow, January 15, 23, 1947). Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 65, 189, 226.

[8] Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 192-193.

[9] CIA studies: “Korea,” SR 2, summer 1947; “The Current Situation in Korea,” ORE 15-48, March 18, 1948;”Communist Capabilities in Korea,” ORE 32-48, February 21, 1949, Carrollton Retrospective Collection, 1981, items 137 B, C, D, 138 A to E, 139A to C, “National Intelligence Survey, Korea, NIS (compiled in 1950 and 1952). Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2., 186.

[10] 895.00 file, box 7124, Maj. Gen. Albert Brown to Hodge, “Political Program for Korea,” February 20, 1947. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2., 186.

[11] Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2., 282, 293, 294, 329. See 312-313 for elaboration on the “the most important relationship, with China.”

[12] 895.00 file box 5691, Drumwright to State Department March 25, 1950. U.S. Senate, Committee on Foreign Relations, Historical Series, Economic Assistance to China and Korea 1949-1950 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1974), 159. New York Times, July 14, July 19, 1950. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2., 339, 376, 467, 468, 694-695.

[13] Ridgway Papers, box 16, Notes on Conference with MacArthur, August 8, 1950. Letter to the New York Times, July 16, 1950. Ridgway Papers, box 16, Notes on Conference with MacArthur, August 8, 1950. Ridgway Papers, box 20, Ridgway to Collins, January 8, 1951. All quoted in Cumings The Origins of the Korean War, v.2, 695.

[14] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2. 65. G-2 Weekly Report no. 93 6/15-22/1947; no.94 June 22-29 1947; no. 98 July 20-27 1947. Cumings, v. 2, 63. Excerpts from conference at Korean Commission, November 18, 1946, Goodfellow Papers, Box 1. Quoted in Cumings The Origins of the Korean War, v.2, 64.

[15] Cumings The Origins of the Korean War, v.2, 99, 143, 144.

[16] Cumings The Origins of the Korean War, v.2,, 142-144.

[17] Ridgway Papers. Ridgway Oral Interview, March 5, 1982. Cited in Cumings The Origins of the Korean War, v.2,, 464; 470.

[18] National Archives, 740.0019 file, box 3827, Marshall’s note to Acheson of Jan. 20, 1947, attached to Vincent to Acheson, January 27, 1947. Quoted in Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 210.

Acheson quote in Cumings The Origins of the Korean War, v.2, 412.

[19] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v.2. 112. David Halberstam, The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War (New York: Hyperion, 2007), 378.

[20] David M. Oshinsky, A Conspiracy So Immense: The World of Joe McCarthy (New York: The Free Press, 1989), 111. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v.2. 109.

[21] New York Times, May 21, April 20, 1950. Quoted in Cumings The Origins of the Korean War, v.2, 562.

[22] New York Times editorials of April 15 and April 19, 1950. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v.2, 109.

[23] Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 247, 219. New York Times, October 24, 2001.

[24] See I.F. Stone, The Hidden History of the Korean War (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1952; reprint, Monthly Review Press, 1971)

[25] A.T. Steele, New York Herald Tribune, October 30, 1949. Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 253 (Steele quote), 248, 274. One account of a genocidal attack on a village can be found in the MacArthur Archives, Norfolk, Virginia, Record Group 6, box 40, Daily Intelligence Summaries, no 2686, January 16, 1950; a similar account is in the same archives, Record Group 9, box 43, U.S. Military Attache to Department of the Army, January 11, 1950. The North ran a smilar account of the incident, but gave the name of the village as Sokbong-ni, and said that rightist youths under ROKA protection were responsible. Their casualty figures were the same as the internal American account. See Nodung Sinmun (Worker’s Daily North). All cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v.2, 401-402.

[26] Cumings reports the following: “With a Thames Television crew I interviewed a brigade leader in the KPA border constabulary, who fought at Song’ak-san. He said the battle began on May 4 with a dawn attack across the parallel by the southern forces, in which they took Hill 291, part of Song’ak-san. He claimed that four hundred ROKA soldiers were killed or wounded. (Interview with Chon Hi Sup, November 1987, Pyong-yang).” Footnote 35, 843. Roberts to Charles Bolte, “Personal Comments on KMAG and Korean Affairs,” August 19, 1949, Xeroxed document held by archivist Robert Taylor, National Archives, room 13W. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v.2, 388, 389 about the Daily Worker, 450.

[27] CIA, National Intelligence Survey, Korea. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v.2, 222. Op cit 232, 390.

[28] Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 245, 246. Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v.2, 284, 444.

[29] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v.2, 162, 383, 494, 496.

[30] Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 252; quoted in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v.2, 396.

[31] “In a secret Interior Ministry message to front-line units dated November 27, 1947, Pak Il-u cited Korean National Police and rightist Northwest Youth forays across the border, saying that with the announcement of the Soviet troop withdrawl, the South Koreans want to “provoke disorders” so that U.S. trooops will not withdraw. See this document in Record Group 242, SA 2005, item 6/11, Samu gwan’gye soryu. A signed article in the June 24, 1949 issue of Hamgyong Namdo Worker’s Daily (North) said that Rhee wants “to start a civil war” to get the U.S. Army to stay in Korea.” Koo Papers box 217, diary entries, February 8, June 28, 29, 1949; oral history, vol. 6, pt. 1, 1-367; See the cable in box 147, cable no. 222, June 29, 1949. Wing Fook Jung is listed in Army Register, 1950. See a “Lt. Col. Jung” of Army G-2 listed in National Archives Lot 55D128, box 381, Korean Log, June 24-25, 1950. Koo’s Chinese-language cable to the Foreign Miinistry in Taipei was dispatched on June 29, 1949, and reads as follows: “According to a secret source the American Government is reviewing and examining the situation in Korea. The source predicts that since the American troops have withdrawn, the North Korean army will invade the South and South Korean government will be unable to resist the invasion … At that time, General MacArthur will have an excuse to send the Seventh Division which has been withdrawn, back to South Korea … We should pay attention to this development.” All cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 384. Op cit. 473.

[32] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 236, 766, 466.

[33] Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 239. Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 358-359.

[34] RG 218. JCS box 130 Section 2 JCS 1483/44 as cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 60.

[35] See Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 432-438, especially 435.

[36] Acheson to William Elliott, August 11, 1960. Acheson Papers (Yale) box 9. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 435.

[37] Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 119, 120.

[38] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 118, 120.

[39] British Foreign Office, FO317, piece no. 84053, Holt to FO, May 1, 1950. As quoted in Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 255.

[40] New York Times, May 27, 1950. Quoted in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 464.

[41] Goodfellow Papers, box 1, Hodge to MPG, January 28, 1947, MacArthur’s August 15 statement is in several sources; see Robert Oliver, Syngman Rhee and American Involvement in Korea, 1942-1960 (Seoul: Panmun Books, 1978), 186. MacArthur’s other trip was to Manila on the granting of “independence” to the Philippines. For Rhee’s October meeting see 895.00 file, box 7126, Muccio to State, November 11, 1948; G-2 Periodic Report, October 22-23, 1948, U.S. Armed Forces in Korea 11071 file; on the October trip see also RG332, XXIV Corps Historical File, loose material for “XXIV Corps Historical Journal,” dated October 19-23, including an Associated Press dispatch from Tokyo dated October 22, 1948, reporting that MacArthur told Rhee he would defend Korea; British Foreign Office 317, piece no. 69944, Gascoigne to British Foreign Office, October 30, 1948. “Archivists responsible for the MacArthur Papers say no transcripts of Rhee-MacArthur talks exist; one told me [Cumings] that MacArthur never kept minutes or transcripts of private meetings. When one day early in the Japan Occupation an officer drew up a transcript of a mundane meeting and asked MacArthur what to do with it, he was told to burn it.” This entire citation is quoted directly from footnote 101, 816-817, Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 234.

[42] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 472.

[43] Harry S. Truman Library, Truman Presidential Secretary File, NSC file, box 208, CIA, “Review of the World Situation,” May 17, 1950; MacArthur Archives, Norfolk, Virginia, Record Group 6, box 58, intelligence summary no. 2825, June 4, 1950; 795.00 file box 4299, Drumwright to State June 9, 1950, citing an undated Tonga ilbo article. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 484-486.

[44] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 487.

[45] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 513, 520, 521, 525, 526.

[46] Office of Chinese Affairs, box 18, Rusk to Acheson, “U.S. Policy Toward Formosa,” May 30, 1950. See also box 17, Hotchkiss/Princetonian Livingston Tallmadge Merchant to Rusk, “Condensed Checklist on China and Formosa,” June 29, 1950. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 538.

[47] Harry S. Truman Library, Acheson Papers, box 45, appointment books, entries for May 1, June 9, 1950. “Rusk’s memorandum of the meeting with Nitze, Jessup, and others on May 30 is actually dated May 31, which suggests it was probably drawn up to show to Acheson that day.” Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 546. Schlesinger scholarly talk in New York Times, June 23, 1950. cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 546. Yale Law School graduate Philip Caryl Jessup became President of the American Society for International Law (1954-1955). Hotchkiss/ Harvard Paul Nitze was an international banker.

[48] Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 257, 259-260. Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 502-503, 607. G-3 Operations file, box 121. Bolte to Ridgway. Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 614.

[49] Gavan McCormack, Cold War/Hot War (Sydney, Australia: Hale and Iremonger, 1983), 97; E. Gough Whitlam, A Pacific Community (Cambridge, Mass.: Australian Studies Endowment and Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University Press, 1981), 57-58. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 547.

[50] Letters, J.W. Burton to Bruce Cumings, November 25, 1981, February 3, 1982; also McCormack, Cold War/Hot War. Interview with Burton, February 1987. Burton subsequently taught international politics at George Mason University. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 547. Wikepedia, subject to CIA interference, contains no reference to anything Korean in John Wear Burton’s on-line biography.

[51] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 476, 571.

[52] New York Times, December 3, 2007. Charles J. Hanley & Jae-Soon Chang, “Thousands Killed by US’s Korean Ally,” Associated Press, May 19, 2008. See also Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 265-266, 286, 289.

[53] Charles J. Hanley and Jae-Soon Chang, “Children Executed in 1950 South Korean Killings,” Associated Press, December 6, 2008.

[54] “U.S. Okayed Korean War Massacres,” Associated Press, July 4, 2008. “South Korea Commission Probes Civilian Massacres by US in Korean War, “Amy Goodman, Democracy Now, August 7, 2008.

[55] Charles J. Hanley, Sang-Hun Choe and Martha Mendoza, The Bridge at No Gun Ri. A Hidden Nightmare From the Korean War (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2001), 281, 285.

[56] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 670-671.

[57] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 472, 474.

[58] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 676-677, 679-680, 683.

[59] U.S. Air Force, Air University, “Preliminary Study,” pt. 3, 106-185. The primary writers of this portion were John Petzel and Clarence Weems. Quoted in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 683.

[60] Ambrose, The Rise to Globalism, 3rd edition, 171.

[61] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 392, 481.

[62] Korean Survey, April 1955, as noted in Cumings The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 62.

[63] Robert Murphy, quoted in John J. Roberts, “The `Japan Crowd’ and the Zaibatsu Restoration,” The Japan Interpreter 12 (summer 1979), 406; on Japanese participation in the landings, see British Foreign Office 317, piece no. 84243, memo by J.H.S. Shattuck, October 28, 1950; Yoshida was quoted in US News and World Report, September 15, 1950. Seoul’s Haebang ilbo reported on July 12, 1950, that KPA units encountered thirty Japanese officers as early as the fighting for Suwon. All the aforementioned cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 664. Labor leader quote from Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 471.

[64] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 711.

[65]I.F. Stone, The Hidden History of the Korean War, xv. Monthly Review lead editorial, 2/4August 1950, 110-117. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 638.

[66] 795.00 file, box 4270, carrying UPI and AP dispatches dated December 16, 17, 18, 1950; British Foreign Office 317, piece no. 92847, original letter from Private Duncan, January 5, 1951; Adams to Foreign Office, January 8, 1951; UNCURK reports cited in Harry S. Truman Library, Truman Presidential Secretary’s File, CIA file, box 248, daily summary, December 19, 1950. See also, December 18, 21, 22, 1950. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 720. London Times

[67] London Times, UPI, December 16, 1950; 795.00 file, box 4299, Muccio to State, October 20, 1950; Harry S. Truman Library, Truman Presidential Secretary’s File, CIA file, box 248, daily summaries for December 19, 20. 21,1950. The CIA reported that UNC officials had made representations to ROK officials about the atrocities, but “appear to have little effect,” The Manchester Guardian reported that American infantry elements saved one woman after coming upon executions being carried out by members of An Ho-sang’s Korean Youth Defense League; twenty-six others, including three women, a nine-year-old boy, and a thirteen-year-old girl, were already murdered: “when they grow up, they too would be communists,” the murderers said (December 18, 1950). The Japanese figure is from Koon Woo Nam, North Korean Leadership, 1945-1965: A Study of Factionalism and Political Consolidation (University, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 1974), 89. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 721.

[68] Goodfellow Papers, Box 1. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 136.

[69] British Foreign Office 317, piece no. 83314, Burgess comments on FC 10338/31, February 2, 1950. Burgess comments in British Foreign Office in FO 317, piece no. 83313. January 30, 1950. Cited in Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 138. 240, for the absence of any proof of Soviet involvement. See George Blake, No Other Choice: an autobiography (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990). And see Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 327, for how “MacArthur’s intelligence, along with the Nationalist Chinese always exaggerated the degree to which Northeast Asia was a single bloc controlled by Moscow, since this served their purposes.”

[70] Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 140.

[71] Sterling and Peggy Seagrave, Gold Warriors. passim.

[72] For the mammoth Lockheed scandal, consult Ben R. Rich and Leo Janos, Skunk Works. A Personal Memoir of My Years at Lockheed (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2004).

[73] Harry S. Truman Library, Presidential Secretary’s File, CIA file, box 250, CIA memo of August 3, 1950. Cumings The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 128.

[74] Cumings The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 457, 643. For Washington’s perfection of aerial slaughter of civilians, see Yuki Tanaka and Marilyn B. Young, ed., Bombing Civilians: A Twentieth–Century History (New York: New Press, 2009).

[75] Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 293.

[76] Williams and Wallace, Unit 731, 246, 245.

[77] Anthony Ugolink, Elijah Kresge Professor at Franklin Marshall College in a letter to the New York Times, March 28, 1993.

[78] Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 296.Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, v. 2, 770.

[79] Thames Television, transcript from the fifth seminar for “Korea: the Unknown War” (Nov. 1986); Thames interview with Tibor Meray (also 1986). Quoted in Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 298.

From A People’s History of US Foreign Policy by Anthony Gronowicz (unpublished).

From A People’s History of US Foreign Policy by Anthony Gronowicz (unpublished).

New York City native, Anthony Gronowicz, is an Associate Editor of the Journal of Labor and Society, and elected faculty adviser of CUNY DIVEST (from fossil fuels). His BA is from Columbia University in European history and his history PhD is from the University of Pennsylvania. He authored Race and Class Politics in New York City Before the Civil War, and edited Oswald Garrison Villard: The Dilemmas of the Absolute Pacifist in Two World Wars. He serves on the twenty-seven-member Executive Council of the Professional Staff Congress (PSC), the City University union for twenty-five thousand faculty and staff. He teaches American and European history and American Government at the Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC) where he started up the college student newspaper and serves as its faculty advisor. From 1999 to 2001 he chaired the University Seminar on the City at Columbia University. In 2013, as the Green Party candidate for mayor, he placed 4th in a field of 15 candidates. He appears as the historical narrator for the documentary film, The Lost Village, that will be shown again at 5 pm on April 26 th at the Cinema Village Theaters 22 East 12 th Street.