Above Photo: Crews clean up an oil spill along Lake Michigan from the BP Whiting refinery in Whiting, Ind., on Tuesday, March 25, 2014. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune/MCT)

HURRICANE IVAN WOULD not die. After traveling across the Atlantic Ocean, it stewed for more than a week in the Caribbean, fluctuating between a Category 3 and 5 storm while battering Jamaica, Cuba, and other vulnerable islands. And as it approached the US Gulf Coast, it stirred up a massive mud slide on the sea floor. The mudslide created leaks in 25 undersea oil wells, snarled the pipelines leading from the wells to a nearby oil platform, and brought the platform down on top of all of it. And a bunch of the mess—owned by Taylor Energy—is still down there, covered by tons of silty sediment. Also, twelve years later, the mess is still leaking.

The Taylor Energy site will continue to leak for the next century, according to the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement. Since the storm, its oil slick stretches over eight square miles on an average day. Meanwhile, Taylor Energy gone bankrupt with only 9 wells plugged, and is suing the federal government for $432 million in trust for leak response, saying there’s nothing left to do. “Taylor is the most blatant example of everything that can go wrong with conventional offshore drilling,” says David Manthos, program coordinator at environmental watchdogging nonprofit SkyTruth.

While the Taylor Energy spill is the worst case scenario, it’s not the US’s only low-profile leaker. Every year thousands of oil and chemical spills occur in waters around the country, but unless you live in a highly impacted area like Louisiana, you probably only hear about a handful of them. That’s partly because the Coast Guard classifies many spills—up to 100,000 gallons—as minor or moderate, and small spills get less of everything: less media attention, less regulation, less environmental impact assessment, and most critically, less funding to clean them up.

It makes sense that not every greasy pelican is national news. But as a group, they probably should be. Oil is toxic. Oil spills, however small, have a cumulative environmental impact. But the regulations in place to prevent them are limited, and in some cases, absurd. For instance, the US Coast Guard basically relies on oil companies to use the honor system when reporting leaks. And since oil leaks happen not only because oil technology is often either too old or too new, but also because of human error, that’s what we call a real conflict of interest.

Size Doesn’t Matter

Oil leaks have been around longer than humans have been drilling. In Gulf of Mexico and off the coast of California, petroleum naturally seeps up through the seafloor. But natural oil seeps are slow, and old. The oil droplets rising through the water from the seafloor create only the thinnest of slicks on the surface, and the organisms that live over these seeps—like oil-gobbling bacteria—have evolved to cope with it. But the majority of ocean life never developed the appetite for oil.

Or much defense against it. Air breathing animals like dolphins and turtles suck in oil if they surface in a slick, and when even small amounts of oil end up in their lungs, they suffer fatal pneumonia-esque health issues. Plants and algae can’t photosynthesize under a grungy film. And even a few molecules of oil can kill fish larvae.

Human physiology isn’t a fan either. “Oil slicks can be very noxious. My graduate students have become ill from the fumes when we’ve gone out there,” says Ian MacDonald, an oceanographer at Florida State University. MacDonald and his students have turned the collapsed Taylor Energy site into something of a lab, because it reliably leaks between 84 and 1,470 gallons per day.

Except, Size Definitely Matters

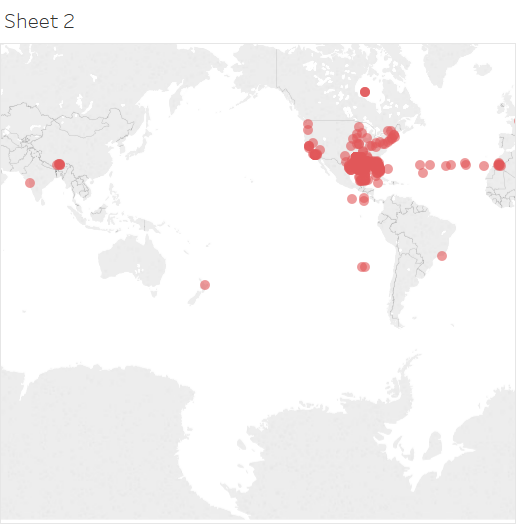

Each red dot above represents an oil spill reported to the National Response Center between 2005 and today. They’re concentrated in the Gulf, but you can zoom out to see spills in other areas, are click on a spill to see when someone reported it.

Even a few thousand gallons of spilled oil is consequential. Even more consequential are more than 30,000 of those so-called small spills each year. Which is probably the bare minimum spill estimate, says Manthos of SkyTruth. Really, it’s hard to know if this figure is complete, and even harder to calculate the volume of oil being leaked. Some new oil equipment is smart enough to know when, and measure how much, it leaks. But those sensors can malfunction. Plus most oil infrastructure is way older. Most of the time oil companies, activists, and the US Coast Guard are all doing some version of educated guessing.

Their biggest clues comes from the size and color of an oil slick. Neither of which are great. “If you’ve ever tried to estimate the size of something in a plane going 200 miles per hour, you know it’s probably off,” says Scott Eustis, a coastal wetlands specialist at the Gulf Restoration Network. Color gives a clues about an oil spill’s thickness. But anyone who has even had one of those ‘What if my blue isn’t the same as your blue, man?’ conversations knows why that could get tricky.

The volumes that oil companies and others do calculate and report get compiled in a National Response Center database. And if you ask an oil lobbyist, it all totals to about one million gallons per year. And those oil company-provided numbers are what the US Coast Guard relies on to levy fines against those that spill. Which is a problem, because oil companies have a financial incentive to lowball the spill estimates, because the fines levied against them often triple if they cross that major spill threshold. “It’s the fox watching the henhouse,” Manthos says.

At SkyTruth, Manthos uses satellite imagery and remote sensing data to get a much more definitive picture of spill size and color than you can get from sticking your head out of a helicopter door. “We make an estimate and compare it to estimate they submit, and they usually don’t add up,” he says. “An environmentally concerned person might have a tendency to overreport. If the report comes from someone working on a oil platform, those volumes are frequently underreported.” And does not account for the many spills that go unnoticed somewhere along the 2.4 million miles of oil pipe in the United States. “There’s so much infrastructure and no one monitoring it,” says Jonathan Henderson, founder and president of environmental watchdog organization Vanishing Earth. “It’s impossible to say how much damage is being done.”

Not for lack of trying. When SkyTruth contributed to a studycomparing oil companies’ estimates to more objective satellite data, they found that on average, the volume of oil spilled is at least 13 times higher than reported—Thirteen million gallons is more than an Exxon Valdez per year. And oil companies don’t need to be accurate. “There are penalties for not reporting something that you should have seen,” Manthos says. “But no penalties for underreporting.”

The Coast Guard’s self-defense on these enforcement matters isn’t too convincing. “The Coast Guard would likely seek enforcement action,” says Lieutenant Katie Braynard. She would not comment more specifically.

Aging Infrastructure and Poor Regulation

American oil infrastructure is old. On this map, each dot represents a still-standing platform or rig. The lighter the dot, the older the construction. The oldest date back to the 1960s. You can click on a rig to see the installation date.

The US government spends a lot of money subsidizing the oil industry—some $5.3 trillion in benefits according to an International Monetary Fund study. But the government does not require the industry to do sweeping upgrades of its aging, leaky equipment.

The infrastructure issues are a mixture of growing pains and poor maintenance. “There’s two ways things go bad,” says Eustis. There’s new stuff, like Deep Water Horizons: under-tested, in deep water, under high pressure, and far from land. But that new stuff is, as you can now guess, rare. Many more leaks come from rust bucket rigs that are chronically broken and patched, instead of rebuilt, says Eustis. These rigs are usually close to shore, have changed hands a few times, and are now operated by the subcontractor of a subcontractor of a subcontractor of a subsidiary of a major oil company. “That’s where the oil production started,” MacDonald says. “Everything close to land is 20, 30 plus years old.” And the older they are, the more they leak.

Many aren’t even operational anymore. According to Henderson, about 36,000 abandoned wells dot the shallow waters of the Gulf of Mexico, sites where the oil companies either drilled and didn’t find anything below the sediment, or sapped a reserve to the point where it made more sense to move resources on to other, juicier wells.

But that doesn’t mean that these wells are exhausted: in many cases small (or not so small) amounts of oil are still hanging out in the reservoir or the pipes connected to it. “There’s all these ticking time bombs out there rusting,” Henderson says. “And it’s inshore too. Thousands of wells and pipelines in the wetlands were abandoned with oil still in them, and because of rising sea levels and coastal erosion, now they’re sitting in salt water and they’re corroding and leaking.” Or sitting in the path of some future hurricane.

An issue of this magnitude clearly isn’t down to a few shady companies. A certain amount of environmental ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ is built into the system. “The process for getting an oil lease is the simplest system in the world: whoever bids the most bonus gets the lease,” says Jacqueline Weaver, a professor at the University of Houston Law Center who specializes in oil and gas law. “There is no real pre-qualification of lessees, no assessment of their fitness to operate.” All they look at now is financial ability. So whether you’re a reputable and responsible oil company, a petrol-curious dude who came into some cash, or the most notorious oil spiller in the galaxy, your chances of expanding your oil empire are equal.

Having few incentives other than financial ones breeds a poor safety culture. “The problem is 80% of the accidents are human error. Some of the actors in shallow water are just very sloppy,” Weaver says. She attributes the situation in part to the cowboy mythos of American oil exploration. As far as they’re concerned, they don’t need help outside their own bootstraps, so they sure as heck don’t need the National Academy of Sciences or government regulation to tell them how to do their jobs.

And that leads to issues that sound insane to an outsider: “On oil rigs, people always turn off all the alarms because they can’t sleep,” Weaver says. “And even if they do leave them on, you don’t notice when there’s an accident because the alarms are always going off.” But to be fair, a sizable portion of the blame for that problem falls at the feet of their managers pushing for more and more oil flowing at faster and faster rates. And those managers are responding to the demands of, well, capitalism’s appetite for oil.

Leaky Past, Leakier Future

Ah, capitalism. Despite environmental concerns, the world, and especially the United States, is still slurping up a lot of oil. And President-elect Trump’s position on offshore oil drilling and preserving the jobs of oil workers makes that unlikely to change in the next four years. But Weaver doesn’t necessarily see a future where every tract of land off US coasts is suddenly fair game. “The net effect of putting a huge amount of land on the market is driving down the price,” she says. “That’s just the United States losing money.”

Besides, new development isn’t nearly as scary as the leaky infrastructure—and regulatory holes—that already exist. Like the Taylor Energy site, with barely a decade of leaks behind it, and many more to come.