Above: Demonstrators with CodePink protest weapon sales to Saudi Arabia outside the Hart Senate Office building on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, September 7, 2016. Photo by Jim Watson for AFP amd Getty Images.

For decades, the American people have been repeatedly told by their government and corporate-run media that acts of war ordered by their president have been largely motivated by the need to counter acts of aggression or oppression by “evil dictators.” We were told we had to invade Iraq because Saddam Hussein was an evil dictator. We had to bomb Libya because Muammar Gaddafi was an evil dictator, bent on unleashing a “bloodbath” on his own people. Today, of course, we are told that we should support insurgents in Syria because Bashar al-Assad is an evil dictator, and we must repeatedly rattle our sabers at North Korea’s Kim Jong-un and Russia’s Vladimir Putin because they, too, are evil dictators.

This is part of the larger, usually unquestioned mainstream corporate media narrative that the US leads the “Western democracies” in a global struggle to combat terrorism and totalitarianism and promote democracy.

I set out to answer a simple question: Is it true? Does the US government actually oppose dictatorships and champion democracy around the world, as we are repeatedly told?

The truth is not easy to find, but federal sources do provide an answer: No. According to Freedom House‘s rating system of political rights around the world, there were 49 nations in the world, as of 2015, that can be fairly categorized as “dictatorships.” As of the fiscal year 2015, the last year for which we have publicly available data, the federal government of the United States had been providing military assistance to 36 of them, courtesy of your tax dollars. The United States currently supports over 73 percent of the world’s dictatorships!

Most politically aware people know of some of the more highly publicized instances of this, such as the tens of billions of dollars’ worth of US military assistance provided to the beheading capital of the world, the misogynistic monarchy of Saudi Arabia, and the repressive military dictatorship now in power in Egypt. But apologists for our nation’s imperialistic foreign policy may try to rationalize such support, arguing that Saudi Arabia and Egypt are exceptions to the rule. They may argue that our broader national interests in the Middle East require temporarily overlooking the oppressive nature of those particular states, in order to serve a broader, pro-democratic endgame.

Such hogwash could be critiqued on many counts, of course, beginning with its class-biased presumptions about what constitutes US “national interests.” But my survey of US support for dictatorships around the world demonstrates that our government’s support for Saudi Arabia and Egypt are not exceptions to the rule at all. They are the rule.

Sources and Methods

It was not easy to find out how many of the world’s dictatorships are being supported by the United States. No one else seems to be compiling or maintaining a list, so I had to go at it by myself. Here is how I came up with my answer.

Step 1: Determine how many of the world’s governments may be fairly characterized as dictatorships. A commonly accepted definition of a “dictatorship” is a system of government in which one person or a small group possesses absolute state power, thereby directing all national policies and major acts — leaving the people powerless to alter those decisions or replace those in power by any method short of revolution or coup. I examined a number of websites and organizations that claimed to maintain lists of the world’s dictatorships, but most of them were either dated, listed only the world’s “worst dictators” or had similar limitations, and/or failed to describe their methodology. I ultimately was left with the annual Freedom in the World reports published by Freedom House as the best source for providing a comprehensive list.

This was not entirely satisfactory, as Freedom House has a decidedly pro-US-ruling-class bias. For example, it categorizes Russia as a dictatorship. In the introduction to its 2017 Freedom In the World report, it opines that “Russia, in stunning displays of hubris and hostility, interfered in the political processes of the United States and other democracies, escalated its military support for the Assad dictatorship in Syria, and solidified its illegal occupation of Ukrainian territory.” A more objective view would note that claims of interference in the US election by the Russian government have not been proven (unless one is inclined to take certain US intelligence agencies at their word); that Russia was asked by the UN-recognized Syrian government for assistance, in compliance with international law (unlike US acts of aggression and support for insurrection there); and would at least acknowledge that any Russian intervention in Ukraine occurred in the context of the United States’ brazen support for a coup in that nation.

Nonetheless, the Freedom House reports appear to be the best (if not the only) comprehensive gauge of political rights and freedoms covering every nation in the world. It utilizes a team of about 130 in-house and external analysts and expert advisers from the academic, think tank and human rights communities who purportedly use a broad range of sources, including news articles, academic analyses, reports from nongovernmental organizations and individual professional contacts. The analysts’ proposed scores are discussed and defended at annual review meetings, organized by region and attended by Freedom House staff and a panel of expert advisers. The final scores represent the consensus of the analysts, advisers and staff, and are intended to be comparable from year to year and across countries and regions. Freedom House concedes that, “although an element of subjectivity is unavoidable in such an enterprise, the ratings process emphasizes methodological consistency, intellectual rigor, and balanced and unbiased judgments.”

One can remain skeptical, but a key consideration is that Freedom House’s pronounced pro-US bias is actually a plus for purposes of this project. If its team of experts tilts toward a pro-US-government perspective, this means that it would indulge every presumption in favor of not categorizing nations supported by the United States as dictatorships. In other words, if even Freedom House categorizes a government backed by the United States as a dictatorship, one can be fairly confident that its assessment, in that instance, is accurate.

For purposes of the present assessment, I used Freedom House’s 2016 Freedom in the World report, even though its 2017 report is now available. I did so because the 2016 report reflects its assessment of political rights and civil liberties as they existed in 2015, which would roughly correspond with the military assistance and arms sales data that I had available for federal fiscal year 2015 (October 1, 2014 – September 30, 2015) and calendar year 2015. (I will work on a new report when such data for fiscal year 2016 becomes available.)

Freedom House uses a scoring system to gauge a nation’s “political rights” and “civil liberties,” in order to rate each country as “free,” “partly free” or “not free,” with a range of scores for each category. It describes its scoring system as follows: “A country or territory is assigned two ratings (7 to 1) — one for political rights and one for civil liberties — based on its total scores for the political rights and civil liberties questions. Each rating of 1 through 7, with 1 representing the greatest degree of freedom and 7 the smallest degree of freedom, corresponds to a specific range of total scores.”

For purposes of deciding whether a nation could be categorized as a “dictatorship,” however, I focused only on the “political rights” scores, classifying nations with a political rights score of 6 or 7 as a dictatorship. This does not mean that civil liberties are unimportant, of course, but the objective here is to assess the degree of absolutism of the political leadership, not freedom of expression, press, etc. Of course, in the overwhelming majority of cases, nations with low political rights scores also have low civil liberties scores. However, a political rights score of 6 or 7 corresponds most closely with our definition of dictatorship, based on Freedom House’s characterization:

6 — Countries and territories with a rating of 6 have very restricted political rights. They are ruled by one-party or military dictatorships, religious hierarchies, or autocrats. They may allow a few political rights, such as some representation or autonomy for minority groups, and a few are traditional monarchies that tolerate political discussion and accept public petitions.

7 — Countries and territories with a rating of 7 have few or no political rights because of severe government oppression, sometimes in combination with civil war. They may also lack an authoritative and functioning central government and suffer from extreme violence or rule by regional warlords.

While it may be debatable whether it is appropriate to consider a country with no “functioning central government” as a dictatorship, I would submit that the label is appropriate if that nation is ruled de facto by warlords or rival armies or militias. In effect, that simply means that it is ruled by two or more dictators instead of one.

By Freedom House’s measure, then, there were 49 nation-states that could be fairly characterized as dictatorships in 2015, as follows:

Afghanistan, Algeria, Angola, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Belarus, Brunei, Burundi, Cambodia, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, China, Democratic Republic of the Congo (Congo-Kinshasa), Republic of the Congo (Congo-Brazzaville), Cuba, Djibouti, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Iran, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Laos, Libya, Mauritania, Myanmar, North Korea, Oman, Qatar, Russia, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Swaziland, Syria, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkmenistan, Uganda, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, Vietnam and Yemen.

It should be noted that Freedom House included in its ratings several other entities with a political rights score of 6 or 7 whose status as an independent state was itself disputed: Crimea, the Gaza Strip, Pakistani Kashmir, South Ossetia, Tibet, Transnistria, the West Bank and Western Sahara. My count of 49 dictatorships in the world in 2015 excludes these subordinated or disputed state territories.

Step 2: Determine which of the world’s dictatorships received US-funded military or weapons training, military arms financing or authorized sales of military weapons from the United States in 2015.

For this step, I relied on four sources, the first two of which took considerable digging to locate:

A. “Foreign Military Training in Fiscal Years 2015 and 2016 Volume I and Volume II (Country Training Activities),” US Department of Defense and US Department of State Joint Report to Congress.

This is the most recent annual report, required by section 656 of the Foreign Assistance Act (FAA) of 1961, as amended (22 U.S.C. § 2416), and section 652 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008 (P.L. 110-161), which requires “a report on all military training provided to foreign military personnel by the Department of Defense and the Department of State during the previous fiscal year and all such training proposed for the current fiscal year,” excluding NATO countries, Australia, New Zealand and Japan.

This report provides data on US expenditures for military training programs under the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program, Foreign Military Financing (FMF) grants, the International Military Education and Training (IMET) program, the Section 2282 Global Train and Equip (GT&E) program, the Aviation Leadership Program to provide pilot training (ALP), and the Foreign Assistance Act (FAA) drawdown program, which authorizes the president to direct the drawdown of defense articles, services and training if an “unforeseen emergency exists that requires immediate military assistance to a foreign country” that cannot be met by other means. Such expenditures are listed by recipient country, in some detail. For purposes of this study, I include expenditures under these programs as US-funded military training.

The report also provides data on US expenditures for narcotics and law enforcement, global peace operations, centers for security studies, drug interdiction and counter-drug activities, mine removal assistance, disaster response, non-lethal anti-terrorism training and other programs that I did not count as military assistance or training for purposes of this survey. It is certainly more than possible that US assistance under these programs could play a role in providing de facto military assistance to recipient countries, but I err on the side of caution.

The report describes the IMET program as including civilian participants, and including training on “elements of U.S. democracy such as the judicial system, legislative oversight, free speech, equality issues, and commitment to human rights.” One could conceivably criticize my inclusion of IMET training, therefore, on the ground that it actually trains foreign civilians and soldiers in democratic, anti-dictatorial values. However, the IMET program is presumably called “military” training and education for a reason. It trains students in “increased understanding of security issues and the means to address them,” and provides “training that augments the capabilities of participant nations’ military forces to support combined operations and interoperability with U.S. forces.” Accordingly, I think it is fair to count IMET as a form of military assistance, while acknowledging that it arguably might, at times, play a pro-democracy role.

B. US Department of State, “Congressional Budget Justification FOREIGN ASSISTANCE SUMMARY TABLES, Fiscal Year 2017.”

Table 3a of this publication provides the actual fiscal year allocations for foreign assistance programs, by country and by account, including the two programs that interest us here, Foreign Military Financing and IMET. In that regard, it is somewhat duplicative of the previous source, but I reviewed it as a check.

C. Department of Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), Financial Policy And Analysis Business Operations, “Foreign Military Sales, Foreign Military Construction Sales And Other Security Cooperation Historical Facts As of September 30, 2015.”

This source provides the total dollar value of military articles and services sold to foreign governments for FY 2015, including the value of agreements for future deliveries and the value of actual deliveries, which I have provided in the table below. It also includes other data on foreign military financing (credit or grants) extended to foreign governments and provides yet another source on IMET training.

D. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), “Transfer of major conventional weapons: sorted by recipient. Deals with deliveries or orders made for year range 2015 to 2016.”

SIPRI provides an interactive tool by which the user can generate a list of major weapons transfers by supplier, all or some recipients, and the year. Although it only counts “major” conventional weapons transfers, I reviewed it as an additional check on the accuracy of the chart. It essentially affirmed the accuracy of the DSCA report but there were some possible anomalies. For example, the DSCA reports only $8,000 worth of military sales to Uganda in FY 2015 but SIPRI reports the transfer of 10 RG-33 armored vehicles, two Cessna-208 Caravan light transport planes, and 15 Cougar armored vehicles in 2015. The discrepancy may be due to the three-month difference between fiscal year 2015 and calendar year 2105, different methods of dating the transfer, differences in valuation or some unknown factor.

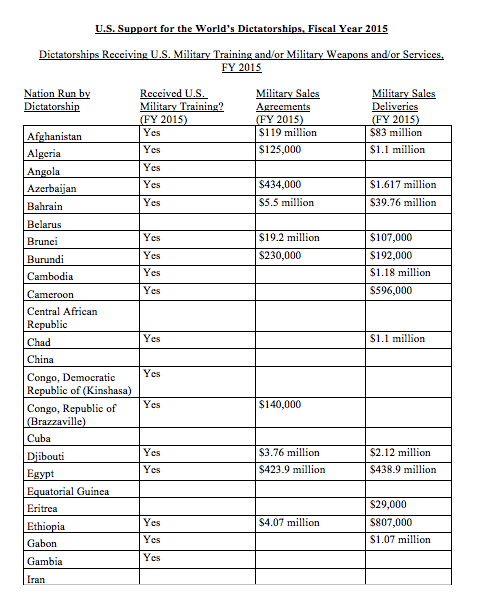

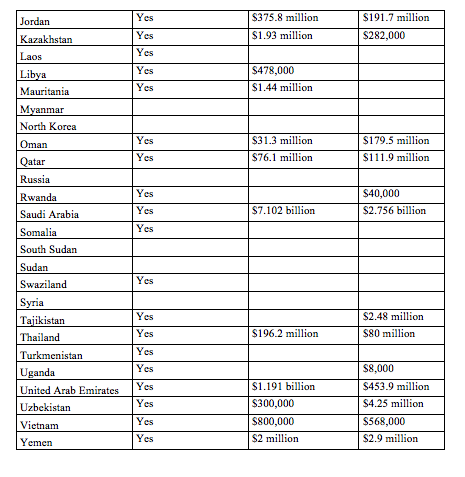

Step 3: Generate the Chart

The first column in the chart below lists the 49 countries classified by Freedom House as dictatorial in nature. The second column shows those nations that received some US military training in FY 2015, relying primarily on source B, but also checking source C. The third column shows those nations that received an agreement for future military sales or transfers from the United States in FY 2015, with the dollar value of the military articles listed, based on source C, but also checking source D. The fourth column shows those nations that received an actual delivery of military articles from the United States in FY 2015, with the dollar value of the military articles listed, based on source C, but also checking source D.

US Support for the World’s Dictatorships, Fiscal Year 2015. (Chart: Rich Whitney)

US Support for the World’s Dictatorships, Fiscal Year 2015. (Chart: Rich Whitney)

I plan on providing similar reports on US support for dictatorships around the world on an annual basis. I will begin work on a report covering Fiscal Year 2016 as soon as the relevant data becomes available.