Above Photo: The lead image of the Washington Post‘s report on 965 people killed by police in 2015 isn’t of any of the victims, but of one of the killer cops: Lisa Meakle, a Pennsylvania officer acquitted of manslaughter for killing an unarmed David Kassick. (photo: Dan Gleiter/AP)

Washington Post Tallies Police Killings–but Holds Back Some of the Numbers That Count

Concerned that official records undercount the number of people shot and killed by police in the United States every year, the Washington Post(12/26/15) attempted to compile a list of every fatal police shooting in 2015. The paper found nearly a thousand such cases—more than twice as many as the FBI reports in a typical year.

The Post‘s project—which corroborates a similar tally conducted by the British Guardian (6/9/15)—is a journalistic accomplishment, as well as an achievement of the Black Lives Matter movement, which has worked to call attention to police violence in the wake of the killing of Michael Brown by police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014.

But it’s hard for me to escape the feeling that the Post story—by Kimberly Kindy and Marc Fisher—was framed by the paper to minimize the project’s remarkable findings. Take the first paragraph that summarizes details of the results:

In a year-long study, the Washington Post found that the kind of incidents that have ignited protests in many US communities—most often, white police officers killing unarmed black men—represent less than 4 percent of fatal police shootings. Meanwhile, the Post found that the great majority of people who died at the hands of the police fit at least one of three categories: They were wielding weapons, they were suicidal or mentally troubled, or they ran when officers told them to halt.

“The kind of incidents that have ignited protests…represent less than 4 percent of fatal police shootings”: That sure sounds like an attempt to play down the number, doesn’t it? Particularly since the write-up never presents the raw number for fatal police shootings of unarmed African-Americans in 2015—which is 37—or the more comprehensive number of all unarmed civilians shot and killed: 90. Those numbers can be found on a graphic that accompanied the story in the paper’s print edition, and in an interactive feature online–but are nowhere to be found in the Post‘s own article on its project. (“Just 9 percent of shootings involved an unarmed victim,” a sidebar accompanying the graphic began—that word “just” indicating that we should read that as “not so many.”)

And the Post‘s “meanwhile,” juxtaposed against “incidents that have ignited protests,” implies that the categories that follow would not inspire protest: those killed “wielding weapons,” who were “suicidal or mentally troubled,” or who “ran when officers told them to halt.”

Actually, people very much protest these sorts of police killings, starting with Michael Brown, who ran when Wilson told him to halt. Laquan McDonald, whose death at the hands of Chicago police has resulted in a first-degree murder charge for officer Jason Van Dyke and the ouster of the city’s police chief, was “wielding” a three-inch knife when he was shot 16 times, so he would have been counted in the first category—as would Tamir Rice, since the Post made the questionable choice to count “toy weapons” in the same category as knives.

The piece stresses that police killings can result from “a single bullet fired at the adrenaline-charged apex of a chase,” and prominently cites the argument of Pennsylvania police union president Les Neri that “officers make split-second decisions” while “their bosses, prosecutors, jurors and the public have the luxury of examining every frame of video.” Neri’s quote becomes the pull quote in the print edition:

“We now microscopically evaluate for days and weeks what they only had a few seconds to act on,” Neri said. “People always say, ‘They shot an unarmed man,’ but we know that only after the fact. We are criminalizing judgment errors.”

With a background in law enforcement, Neri must be aware that people can be prosecuted for judgment errors that result in death; that’s why there’s a crime called criminally negligent homicide. Yet the piece presents his argument at length as though it were a novel legal concept to hold people criminally responsible when their bad decisions end up killing people.

The Post‘s delicate approach to police killings can be appreciated by comparison with the Guardian‘s similar project. For one thing, the Guardian contrasts the numbers with statistics on police killings in Europe, so you can see that the rate at which US cops kill people is far out of line with the frequency of such deaths in comparable countries. For example, England and Wales had 55 fatal police shootings in the last 24 years, while the US had 59 in just 24 days. (The higher level of crime in the US explains some but not much of this difference; the US murder rate is about four times the UK’s, but has a rate of police killings about 70 times as high.)

The Post‘s delicate approach to police killings can be appreciated by comparison with the Guardian‘s similar project. For one thing, the Guardian contrasts the numbers with statistics on police killings in Europe, so you can see that the rate at which US cops kill people is far out of line with the frequency of such deaths in comparable countries. For example, England and Wales had 55 fatal police shootings in the last 24 years, while the US had 59 in just 24 days. (The higher level of crime in the US explains some but not much of this difference; the US murder rate is about four times the UK’s, but has a rate of police killings about 70 times as high.)

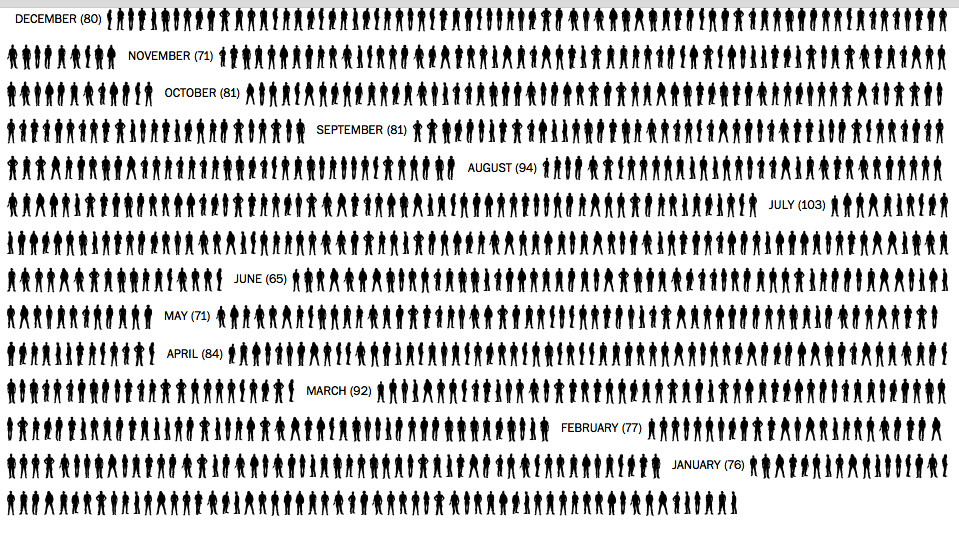

More viscerally, it’s instructive to compare how the two papers visualize the toll of police killings. In the print edition of the Washington Post, those killed by police are represented by what appear to be stylized bullets—with black dots on the ones that represent African-Americans. On the Post website, the dead appear as stereotyped silhouettes:

On the Guardian site, by contrast, the dead are represented, when possible, by actual photos—revealing themselves not as a set of statistics or a collection of weapons wielded, but as individuals, each a unique human life lost as the result of a police decision. An appreciation of that fact, more than anything, is what’s missing from the Washington Post‘s tally of fatal police shootings.